COPD: the GOLD 2024 report

Anne Rodman

Anne Rodman

RGN, MSc

Advanced Nursing Practice, PGDip Respiratory care,

Independent Respiratory Nurse specialist, COPD and ILD course tutor, Rotherham Respiratory

Practice Nurse 2024;54(2):16-19

While the latest iteration of the well-respected – and regularly updated – GOLD report does not represent a major revision, general practice nurses should familiarise themselves with its recommendations. We explore the implications of the 2024 report for practice, and revisit basic principles of COPD care, with practical tips for clinicians

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) remains a major public health problem worldwide, as well as a significant health and social burden on people with COPD and their families, with prevalence projected to increase.1 Not only that but there is evidence that services for patients with COPD have still not fully recovered since the COVID-19 pandemic.2

A survey by Asthma + Lung UK found that the pandemic, together with ongoing pressures on the NHS, have contributed to increasingly delayed access to timely COPD diagnosis and to quality COPD care.2 It is therefore more important than ever to provide effective care based on current guidelines. The NICE guideline on COPD was last updated in 2019,3 while the international Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) guidelines are updated annually.4

DEFINITION

The current GOLD definition of COPD stresses the heterogeneous nature of the lung condition, which is characterised by chronic respiratory symptoms such as dyspnoea, cough and sputum production. This is due to abnormalities of the airways (bronchitis, bronchiolitis) and/or of the alveoli (emphysema) causing persistent and often progressive airflow obstruction. This definition indicates some of the important history and investigations needed for an accurate diagnosis of COPD. GOLD further details the risk factors for COPD including long term environmental exposure to inhaled substances such as tobacco and biomass fuel burning, but also genetic host factors leading to accelerated lung ageing. The best understood of these is the genetic mutation causing deficiency of alpha 1 antitrypsin.

COPD SCREENING

GOLD estimates the global prevalence of COPD to be 10.3% and rising, but suggests that screening for COPD in asymptomatic individuals using spirometry is not an effective approach. However, active case finding using symptoms and risk factors in questionnaires, or selective data – such as age, smoking status, breathlessness, cough and chest infections – that can be identified from primary care databases, followed by spirometry is most likely to lead to earlier diagnosis of COPD and therefore is recommended by GOLD.

Lung cancer and COPD share the same risk factors, and COPD is a major risk factor for lung cancer.5 In many countries, targeted lung cancer screening programmes aim to improve early diagnosis of lung cancer using low dose computed tomography (LDCT) of the chest in older adults with a smoking history. Adding spirometry to the lung health checks for lung cancer has been shown to be an effective screening tool to identify COPD earlier, e.g. in more than half of cases where emphysema is found on the LDCT scan there is obstruction on spirometry.6

The UK NHS lung health check programme7 will be rolled out nationally by 2029 and is already available in some areas. Eligible people should be encouraged to attend. GOLD also suggests that patients who have incidental findings suggestive of COPD on imaging results such as routine chest X-ray, should be prioritised for spirometry.

DIAGNOSIS

Where COPD is suspected, based on the typical pattern of symptoms and risk factors, the diagnosis is confirmed by demonstrating persistent obstruction of airflow. This is identified on spirometry by an abnormally low ratio that does not return to normal.

Missed or delayed diagnosis of COPD is common. The possibility of COPD in younger people due to early life events or genetic predisposition may be missed due to lack of awareness or mislabelling as asthma. This is categorised by GOLD as ‘young COPD’ and affects individuals between the age of 20-50 who have persistently obstructive lung function and earlier decline. GOLD further describes a category of ‘pre-COPD’ where individuals have symptoms consistent with COPD, but show no obstruction on spirometry. Most commonly, they show a preserved (normal) ratio but a reduced FEV1 (<80% predicted), which GOLD terms Preserved Ratio Impaired Spirometry (PRiSM). This is more commonly found in females and smokers, and up to a third of affected individuals will develop obstruction over time, so should be considered as at increased risk of COPD.

Running a simple search in primary care looking at both smoking history and consultations for lower respiratory tract infections will produce a list of people who could be offered spirometry to identify the presence not only of chronic obstruction, but also PRiSM. General practice nurses working in a triage or minor illness role should be alert to the possibility of COPD in patients presenting with chest infections, especially in the winter months, and should ask about any underlying breathlessness or chronic productive cough, smoking history, occupational risk factors and family history of chest problems.

Adults on asthma registers who have a smoking history have the potential to develop chronic lung damage, especially where there is a pattern of poor asthma control or unscheduled care attendance for asthma exacerbations. GOLD states that asthma is an independent risk factor for the development of chronic obstruction, irrespective of smoking status, with around 20% of people with asthma developing irreversible changes in lung function; higher blood eosinophil levels in asthma also predict the development of COPD in later life.

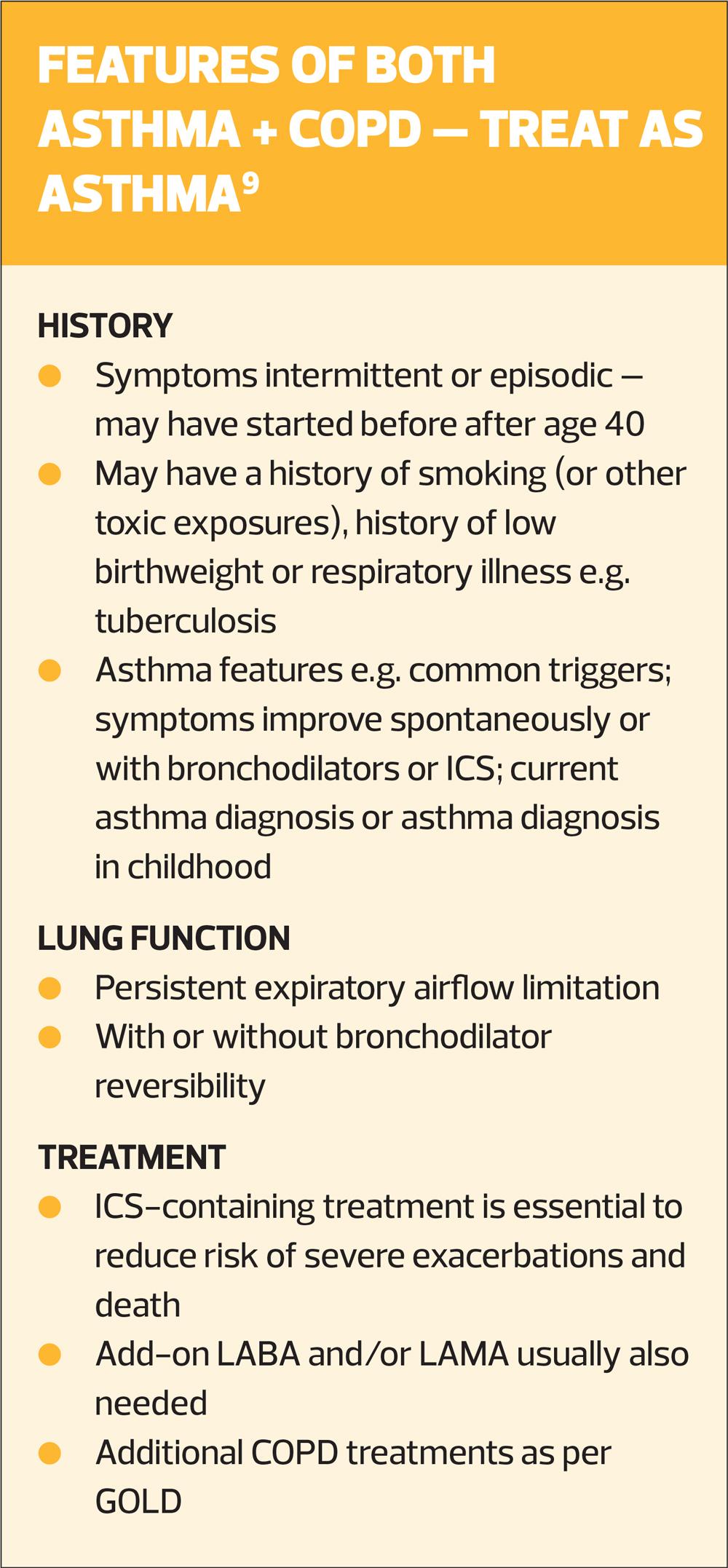

The Primary Care Respiratory Society (PCRS) notes that peak flow monitoring has weak specificity for identifying persistent obstruction in its early stages. Microspirometry, using a handheld device, might therefore be a useful aid to the assessment of asthma, particularly where the patient is symptomatic or shows features of poor control.8 It is quick, cheap and low risk but could identify patients who need to be referred for a quality assured spirometry test, which can more reliably identify early obstruction due to changes of COPD or as a feature of poorly controlled asthma. The key difference in identifying chronic obstruction is that in asthma the lung function should show significant improvement or return to normal with regular inhaled corticosteroid treatment. However, people who have both asthma and COPD continue to show persistent airway obstruction and symptoms even with regular asthma treatment. GOLD emphasises that where asthma and COPD co-exist in the same patient their treatment should follow asthma guidelines. The Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA) has a useful chapter on asthma and COPD with a clear outline of how to identify and manage people with both asthma and COPD (Box 1).9

Spirometry

There are three main types of spirometry tests that are used in respiratory diagnosis.10

- Baseline spirometry where no inhaled medication has been used is the most common initial test for a new diagnosis.

- Post bronchodilator testing is suitable for monitoring of COPD where patients should have taken their usual inhalers before the test.

- Reversibility testing is recommended where any element of asthma is suspected and should follow a standardised procedure where the base and post bronchodilator tests are separated by administration of a specific dose of bronchodilator, with a minimum time gap before the post bronchodilator test depending on the type of bronchodilator used.

All tests must meet quality assurance criteria. Current acceptability and repeatability criteria for adult spirometry can be found on the Association for Respiratory Technology and Physiology (ARTP) website in the updated standards documents.11

NICE and GOLD have historically recommended that diagnosis of COPD should be based on quality assured, post-bronchodilator spirometry, but GOLD, in this latest update, now recommends that baseline spirometry showing obstruction, combined with a careful history detailing symptoms and risk factors for COPD is adequate for making the diagnosis. In practical terms this removes the need for a separate post-bronchodilator test to be performed in someone with suspected COPD and no history or features of asthma. However, GOLD stresses there is still a place for performing a post bronchodilator test, where the initial spirometry is unexpectedly normal in a patient in whom there is a very strong suspicion of COPD.

INITIAL ASSESSMENT

The presence of obstruction (abnormal ratio) on spirometry is further categorised by GOLD and NICE from mild to very severe according to the percentage of predicted FEV1. This is considered to be a simple and reliable way of grading lung function abnormalities. In the UK a proposed revised classification of obstruction is recommended by the ARTP and used as part of their assessment for the qualification of competency in interpretation.12 The ARTP grading of obstruction has five levels and is based on z-scores. These are considered to be a more accurate way of identifying abnormalities in individuals, removing possible biases due to age, sex and height when percentage of predicted values are used – see Spirometry – moving forward towards early and accurate diagnosis, Practice Nurse 2023;53(5):11-16

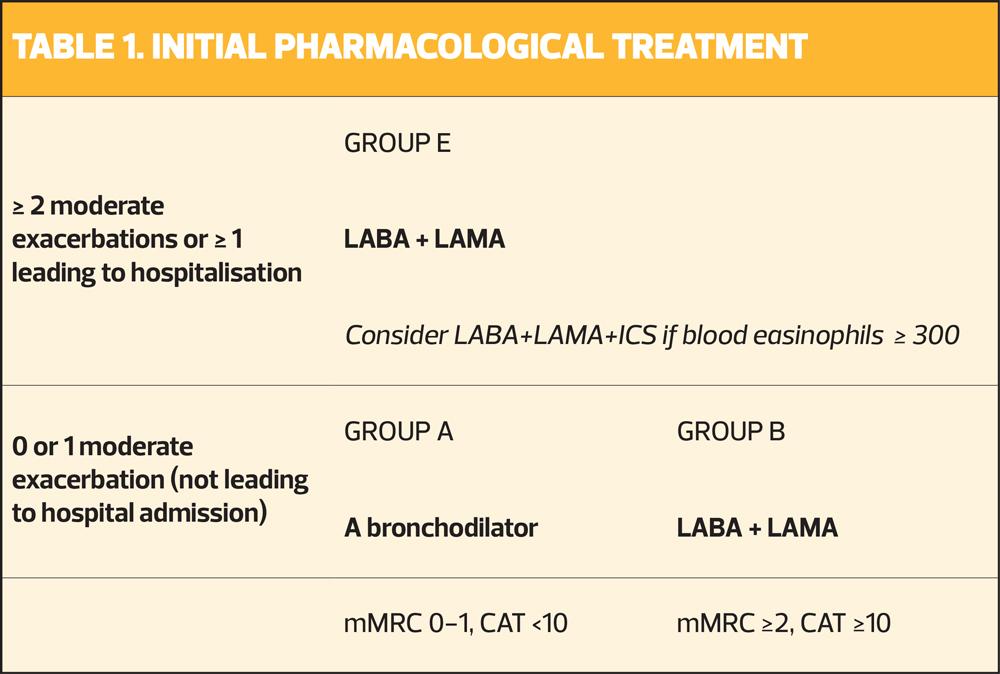

It is important to remember that the above gradings relate explicitly to the degree of obstruction and not to the severity of COPD. This requires a more holistic assessment incorporating symptoms and risk factors. GOLD uses the modified Medical Research Council breathlessness scale (mMRC) and the COPD assessment test score (CAT) to categorise symptoms into:

- Group A – low symptoms (mMRC 0-1, CAT <10)

- Group B – high symptoms (mMRC ≥2, CAT ≥10).

These two categories are further divided according to exacerbation history:

- Group E – ≥2 moderate exacerbations, or 1 requiring hospital admission, in the 12 months prior to the date of assessment.

This is important because it will influence initial treatment decisions.

GOLD continues to recommend further tests where symptoms appear out of proportion to the degree of obstruction. For example, full pulmonary function testing (PFTs) can reveal increased residual volume (gas trapping) that can worsen breathlessness during exercise. PFTs also include measurement of gas transfer using carbon monoxide diffusion capacity in the lungs (DLco). Low diffusion capacity is associated with accelerated decline in COPD.

Other important considerations include excluding co-morbidities such as cardiovascular disease contributing to increased breathlessness, or underlying bronchiectasis as a driver of increased exacerbation frequency.

TREATMENT

GOLD recommendations for initial inhaled treatment – after categorisation into groups A,B or E – are shown in Table 1. GOLD recommends LABA+LAMA combination bronchodilators which have been shown to reduce exacerbation frequency, compared with single bronchodilators. The presence of elevated blood eosinophils should also influence treatment choices. Higher blood eosinophil count (≥300 cells/µl) (or concomitant asthma) predict a benefit in Group E patients for treatment with LABA+LAMA+ICS. Conversely, lower blood eosinophil counts ≤100 cells/µl indicate lack of benefit of ICS in patients with COPD. GOLD cautions that those who may suffer potential harm from long term ICS treatment include any COPD patient with a history of repeated pneumonia or any past mycobacterial infection.

ADHERENCE AND INHALER TECHNIQUE

Choice of inhaler should follow local formularies and incorporate environmental considerations where appropriate.13 However, medication adherence in COPD is known to be poor, with depression and fear of side effects foremost among reasons for non-adherence.14 GOLD has expanded on ways to improve adherence and inhaler technique in the 2024 report. Suggestions include

- Consider patients’ beliefs and satisfaction regarding previous inhaled therapies

- Share decision making over the choice of device, allowing for patient preferences

- Use one consistent device type for individuals

- Avoid any switching of device without patient involvement, education and follow up

- Assess levels of cognition, dexterity and inhalation techniques before prescribing any device

- Clinicians should only prescribe devices that they know how to use

NON-PHARMACOLOGICAL MANAGEMENT

All guidelines, including GOLD, stress the important role of non-pharmacological management alongside pharmacological treatments. Asthma+Lung describes the five fundamentals of care for which access continues to be problematic across the UK.2 These are

- Smoking cessation

- Vaccinations

- Pulmonary rehabilitation

- Self-management education

- Effective management of co-morbidities

GOLD does not recommend the use of e-cigarettes or vapes as a smoking cessation aid in COPD. Using a structured framework to discuss smoking behaviour such as ‘Very brief advice’ (VBA) is more likely to prompt smokers to consider a quit attempt.15 VBA training is available free from the National Centre for Smoking Cessation Training website.16

Vaccinations are important in reducing risk of hospitalisation and mortality in COPD. UK recommendations include influenza, pneumococcal and COVID vaccines for people with COPD as they are categorised as in a clinical risk group. Vaccine scepticism has increased since the pandemic and it is important to acknowledge patients’ concerns whilst providing objective reassurance about the balance of risks and benefits, as this has been shown to increase uptake of vaccinations.17

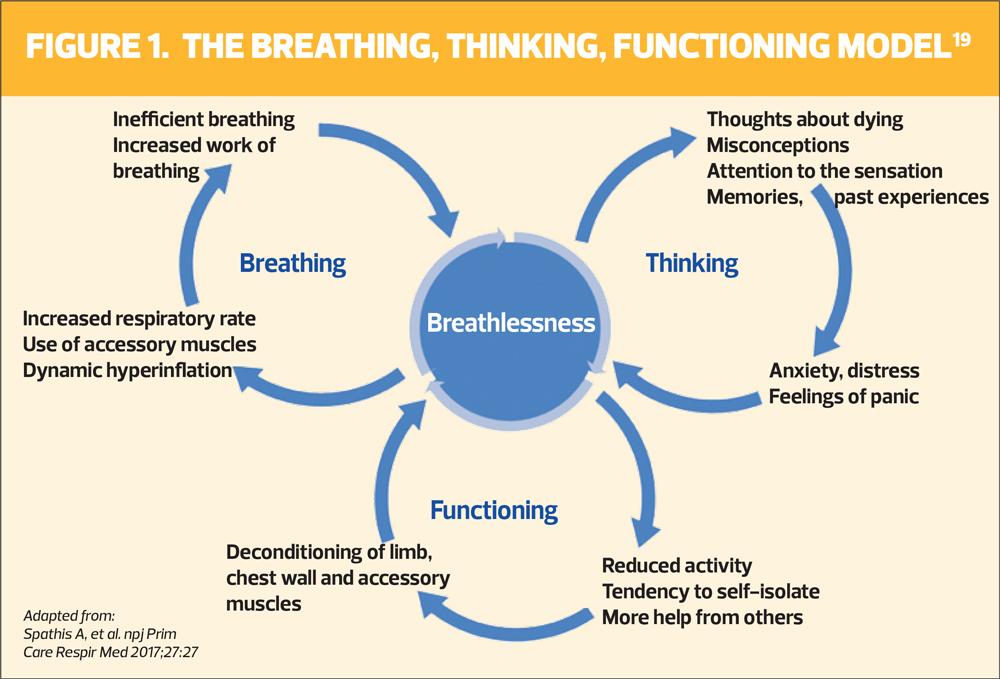

Access to, and uptake of, pulmonary rehabilitation (PR) programmes in the UK has declined since the pandemic.2 GOLD recognises the challenges of promoting physical activity in those with COPD, but there is compelling evidence for PR as the most effective strategy to improve breathlessness, health status and exercise tolerance. In addition to tailored exercise, PR programmes include education on breathlessness management and self-management skills. These have proven benefits in reducing the impact of exacerbations. In particular, a small study in 2022 found patients who had breathlessness management skills were more likely to use rescue packs appropriately and cope better with the onset of an exacerbation.18

Where access to PR is limited or patients decline referral, there are a number of online resources available on the Asthma+Lung website that can help patients become more active and more knowledgeable about their condition (https://www.asthmaandlung.org.uk/living-with). All clinicians involved in COPD care should familiarise themselves with such options for patient support and education, particularly regarding breathlessness management. The Breathing, Thinking, Functioning model of breathlessness19 can help those with COPD understand better what drives breathlessness, and why inhalers alone can improve, but not remove, this symptom completely (Figure 1).

SUMMARY

This article has explored the main changes in the 2024 GOLD COPD report, suggesting how these could be incorporated into a UK primary care setting to better manage COPD. Essential aspects of COPD diagnosis, including identifying those at risk of developing COPD have been revisited. Pharmacological and non-pharmacological strategies are equally important in helping people manage symptoms and reduce exacerbation risk to achieve a better quality of life. The full GOLD report is recommended further reading to gain greater knowledge in this respect, and you can find Practice Nurse's summary of the GOLD 2023 guidance here.

REFERENCES

1. Boers E, Allen A, Barrett M, et al. The economic and health burden of COPD in Western Europe: Forecasting through 2050. Epidemiology. 2023 Sept 9; doi:10.1183/13993003.congress-2023.pa1029

2. Asthma+Lung UK. COPD survey 2022: Delayed diagnosis and unequal care. https://www.asthmaandlung.org.uk/conditions/copd-chronic-obstructive-pulmonary-disease/world-copd-day/delayed-diagnosis-unequal-care

3. NICE NG115. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in over 16s: Diagnosis and management. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/NG115

4. Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease. 2024 Gold Report; 2023 https://goldcopd.org/2024-gold-report/

5. Perrotta F, D'Agnano V, Scialò F, et al. Evolving concepts in COPD and lung cancer: a narrative review. Minerva Med. 2022 Jun;113(3):436-448.

6. Balkan A, Bulut Y, Fuhrman CR, et al. COPD phenotypes in a lung cancer screening population. Clin Respir J 2014 Jul 28;10(1):48–53. doi:10.1111/crj.12180

7. NHS. Lung health checks. https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/lung-health-checks/

8. Primary Care Respiratory Society. Peak flow monitoring and microspirometry as aids to respiratory diagnosis. https://www.pcrs-uk.org/sites/default/files/resource/2023-May-PCRU-Respiratory-diagnosis-Primary-Care.pdf

9. Global Initiative for asthma (GINA). 2023 Gina Main Report; 2023 https://ginasthma.org/2023-gina-main-report/

10. British Thoracic Society. Primary Care Commissioning: A guide to performing quality assured diagnostic spirometry;2013 https://www.brit-thoracic.org.uk/media/70454/spirometry_e-guide_2013.pdf

11. Association for Respiratory Technology and Physiology. Resources. https://www.artp.org.uk/resources/spirometry-standards

12. Sylvester KP, Clayton N, Cliff I, et al. ARTP statement on Pulmonary Function Testing 2020. BMJ Open Respiratory Research. 2020 Jul;7(1)doi:10.1136/bmjresp-2020-000575

13. NHS England. Delivering a Net Zero National Health Service; 2022. https://www.england.nhs.uk/greenernhs/publication/delivering-a-net-zero-national-health-service/

14. Bhattarai B, Walpola R, Mey A, et al. Barriers and strategies for improving medication adherence among people living with COPD: A systematic review. Respir Care 2020;65(11):1738–50.doi:10.4187/respcare.07355

15. Primary Care Respiratory Society. PCRS pragmatic guides for clinicians: Diagnosis and management of tobacco dependency; 2019 https://www.pcrs-uk.org/sites/default/files/tobacco_dependency_pragmatic_guide_2.pdf

16. National Centre For Smoking Cessation Training (NCSCT). Very Brief Advice on Smoking (VBA+); 2022. https://elearning.ncsct.co.uk/

17. Murdan S, Ali N, Ashiru-Oredope D. How to address vaccine hesitancy; 2021. Pharmaceutical Journal. https://pharmaceutical-journal.com/article/ld/how-to-address-vaccine-hesitancy.

18. Hutchinson A, Russell R, Cummings H, et al, P139 Patient recognition of, and response to, acute exacerbations of COPD is related to previous experiences of help-seeking. Thorax 2022;77:A156 https://doi.org/10.1136/thorax-2022-BTSabstracts.274

19. Spathis A, Booth S, Moffat C, et al. The Breathing, Thinking, Functioning clinical model: a proposal to facilitate evidence-based breathlessness management in chronic respiratory disease. npj Prim Care Respir Med 2017;27:27 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5435098/

Related guidelines

View all Guidelines