COPD: GOLD 2023

Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) 2023 Report

Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) 2023 Report

Practice Nurse 2023;53(1): published online first; 9 February 2023

The GOLD 2023 report represents a major revision of the 2022 report, with a new definition of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), a new assessment tool, and new information on the choice of inhaler device.

COPD is one of the top three causes of death worldwide, and many people suffer from the disease for years and die prematurely from it or its complications. The burden of COPD is projected to increase over the coming years because of continued exposure to COPD risk factors and population ageing. GOLD has expressed concern that the disease is not taken seriously enough at any level, from individuals to government, and has says it is time for this to change.

DEFINITION

GOLD has clarified the definition of COPD as a heterogenous lung condition, characterised by chronic respiratory symptoms:

- Dyspnoea

- Cough

- Sputum production, and

- Exacerbations

Symptoms are due to abnormalities of the airways (bronchitis, bronchiolitis) and/or alveoli (emphysema) that cause persistent, often progressive, airflow obstruction.

COPD results from gene(G)-environment(E) interactions occurring over the lifetime of the individual — GETomics — that can damage the lungs and/or alter their normal development/ageing.

The key environmental factors leading to COPD are tobacco smoking and the inhalation of toxic particles and gases from household and outdoor air pollution. In people who have never smoked, air pollution is the leading known risk factor for COPD: the risk is dose-dependent, with no apparent 'safe' threshold.

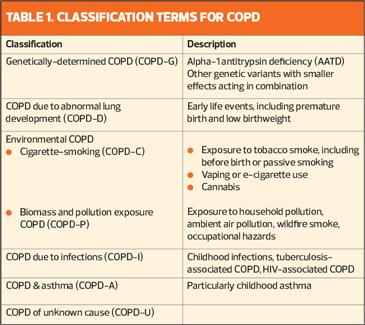

The classification of COPD aetiology is shown in Table 1.

Early, mild or young COPD?

'Early' means 'near the beginning of a process'. In COPD, which can start early in life and take many years to reach clinical manifestation, identifying 'early' COPD is difficult. Some clinical studies have used 'mild' airflow obstruction as a substitute for 'early' disease, but this is incorrect as not everyone with COPD starts from a normal peak lung function in early childhood, and some may never suffer from 'mild' disease in terms of severity of lung function. 'Mild' should not, therefore, be used to identify early COPD, but only to describe the degree of severity of airflow obstruction measured with spirometry. Young COPD should be used to describe the condition occurring in patients aged 20-50 years. Such patients often report a family history of respiratory diseases and/or events such as hospitalisation before the age of 5 years, supporting the possibility that COPD has its origins in early life.

DIAGNOSTIC CRITERIA

The presence of non-fully reversible airflow limitation (FEV1/FVC <0.7 post-bronchodilation) measured by spirometry confirms the diagnosis. But some individuals may present with structural lung lesions (e.g. emphysema) or physiological abnormalities, including low-normal FEV1, gas trapping, reduced lung diffusing capacity and/or rapid FEV1 decline. These are termed 'pre-COPD'. The term 'PRISm' (preserved ratio impaired spirometry) has been recommended to identify patients with normal ratio but abnormal spirometry. Patients with either pre-COPD or PRISm are at risk of developing airflow obstruction, but not all of them do so.

Presentation

Patients with COPD typically complain of breathlessness, activity limitation, and/or cough with or without sputum production, and they may experience exacerbations (acute events with increased respiratory symptoms) that affect their health status and prognosis, and which need specific prevention and treatment. Patients may also often have other comorbid conditions that can affect their COPD and prognosis, and which can mimic or aggravate an exacerbation.

Opportunities

Extensive under- and misdiagnosis of COPD leads to patients receiving incorrect treatment or no treatment at all. Recognising that environmental factors other than smoking can lead to COPD, that it can start early in life and affect young people, and that there are precursor conditions (pre-COPD or PRISm) presents new opportunities for prevention, early diagnosis, and prompt and appropriate treatment.

DIAGNOSIS

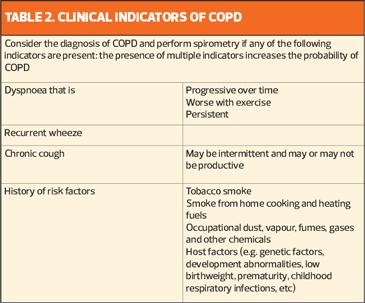

A diagnosis of COPD should be considered in any patient who has dyspnoea, chronic cough or sputum production, a history of lower respiratory tract infections and/or a history of exposure to risk factors for the disease, but GOLD says that the presence of a post-bronchodilator FEV1/FVC <0.7, confirmed on spirometry, is mandatory to establish the diagnosis of COPD. Clinical indicators of COPD are summarised in Table 2.

Chronic dyspnoea is the cardinal symptom of COPD, while cough with sputum production occurs in around 30% of patients. Symptoms may vary over time, and may be present for many years before the development of airflow obstruction. Dyspnea should be measured by the 5-level modified Medical Research Council (mMRC) scale.

Airflow obstruction may also occur without breathlessness or cough and sputum production, and vice versa. And although airflow obstruction is the basis for a diagnosis of COPD, the decision to seek help is usually made because the patient is experiencing chronic respiratory symptoms or has had an acute exacerbation of their symptoms.

Chronic cough is often the first symptom of COPD, but may be dismissed by the patients as an expected consequence of smoking or other environmental exposures.

Patients with COPD commonly produce sputum with coughing, but this may be difficult to quantify because patients may swallow it rather than expectorating it. Sputum production can be intermittent, with periods of flare-up and remission. The presence of purulent sputum suggests an increase in inflammatory mediators and may identify the onset of a bacterial exacerbation.

GOLD uses FEV1/FVC <0.7 as the diagnostic criterion, but warns that using a fixed ratio may result in over-diagnosis in the elderly, and underdiagnosis in young adults, especially in mild disease, compared with using a cut-off based on lower limit of normal (LLN) values, but there are no studies validating the use of LLN in populations where smoking is not the major cause of COPD.

Assessment of airflow obstruction based on a single measurement of the post-bronchodilator FEV1/FVC ratio should be confirmed by repeat spirometry if the value is between 0.6 and 0.8. Assessing the degree of reversibility of airflow obstruction (i.e. measuring FEV1 before and after bronchodilator or corticosteroids) to inform treatment decisions is no longer recommended.

SCREENING AND CASE-FINDING

The role of screening spirometry for the diagnosis of COPD in the general population is controversial. In asymptomatic individuals without any significant exposure to tobacco or other risk factors, screening spirometry is probably not indicated, but in people with symptoms or risk factors (e.g. >20 pack-years of smoking, recurrent chest infections, early life events) it can be useful for early case finding.

ASSESSMENT

Once the diagnosis of COPD has been confirmed by spirometry, assessment to guide therapy should focus on:

- Severity of airflow limitation

- Nature and severity of current symptoms

- Previous history of moderate and severe exacerbations

- Presence and type of other diseases.

The initial COPD assessment aims to establish the severity of airflow obstruction, how the disease affects the patient's health status and to predict the risk of future exacerbations, hospital admissions, or even death, to select appropriate treatment.

Because there is only a weak correlation between severity of airflow obstruction and symptoms, formal assessment of symptoms using validated questionnaires is also needed. GOLD grades of severity of COPD can be found in Table 3.

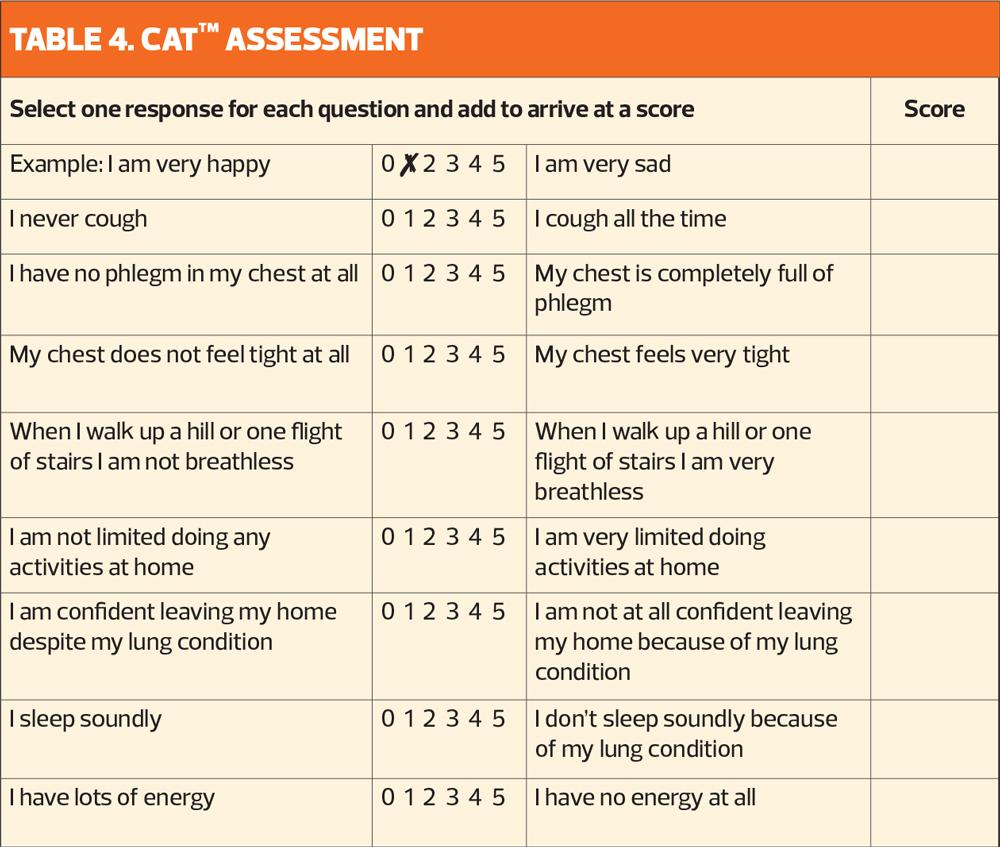

GOLD recommends the use of the COPD Assessment Test (CATTM) rather than the St George's Respiratory Questionnaire (SGRQ) which is too complex for routine clinic use.

CATTM is an 8 item questionnaire that is used to assess health status in patients with COPD. The score ranges from 0 to 40. See Table 4.

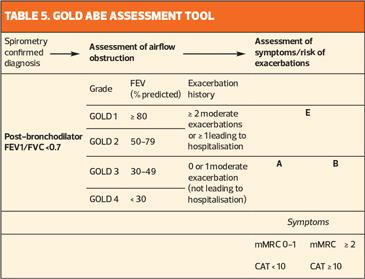

The ABE assessment tool

GOLD has revised its ABCD assessment tool, and now recommends the use of a new, slightly simpler version, the ABE assessment tool (Table 5).

In 2011, GOLD moved from a simple spirometric grading system for disease severity assessment and treatment to a combined assessment strategy based on the level of symptoms (mMRC or CATTM), the severity of airflow limitation (GOLD grades 1—4, Table 3) and frequency of previous exacerbations. This classification was designed to guide treatment decisions.

The severity of airflow obstruction was subsequently removed from the combined assessment tool, given its lack of precision at the individual level.

Now, GOLD has put forward a further evolution of the ABCD combined assessment tool that reflects the clinical importance of exacerbations independent of the patient's symptoms. The A and B groups remain unchanged but the C and D groups are merged into a single group E, which recognises the clinical significance of exacerbations.

Additional clinical assessment, including the measurement of lung volumes, diffusion capacity, exercise testing and/or lung imaging may be considered in COPD patients with persistent symptoms after initial treatment. GOLD recommends chest CT imaging should be considered for patients with:

- Persistent exacerbations

- Symptoms out of proportion to disease severity on lung function testing

- FEV1 less than 40% predicted with significant hyperinflation, or

- For those who meet criteria for lung cancer screening.

Comorbidities occur commonly in patients with COPD, and include cardiovascular disease, skeletal muscle dysfunction, metabolic syndrome, osteoporosis, depression, anxiety, and lung cancer (given the risk factors that COPD and lung cancer have in common). GOLD urges clinicians to actively seek out and optimise treatment of comorbidities, because they will have a negative effect on health status, risk of hospitalisation and mortality, independently of the severity of airflow obstruction due to COPD.

PHARMACOTHERAPY

Pharmacological treatment can reduce COPD symptoms, reduce the frequency and severity of exacerbations, and improve health status and exercise tolerance.

Each regimen should be tailored to the individual and guided by the severity of symptoms, risk of exacerbations, side effects, and comorbidities, as well as the patient's response, preference and ability to use their inhaler.

Patients with COPD should be offered vaccinations for flu and pneumococcus (to decrease the incidence of lower respiratory tract infections); COVID-19; and, if not vaccinated in adolescence, the triple pertussis, tetanus and diphtheria vaccination.

Bronchodilators

Inhaled bronchodilators are central to symptom management and are usually given on a regular basis to prevent or reduce symptoms. Regular and as needed use of short-acting beta agonists (SABA) and short-acting antimuscarinics (SAMA) improves FEV1 and symptoms. Combinations of SABA and SAMA are superior to either medication alone in improving lung function and symptoms.

Long-acting beta agonists (LABA) and long-acting antimuscarinics (LAMA) significantly improve lung function, breathlessness, and health status, and reduce exacerbation rates, but LAMAs have a greater effect on exacerbation reduction compared with LABAs, and decrease hospitalisations. Using them in combination increases FEV1 and reduces symptoms compared with monotherapy, and is also more effective at reducing exacerbations than either alone. A combination inhaler may be more convenient for patients, and more effective, than multiple inhalers.

Inhaled corticosteroids (ICS)

Most studies have found that regular treatment with ICS alone does not alter the long-term decline in FEV1 or mortality in patients with COPD. Regular ICS treatment increases the risk of pneumonia, especially in patients with severe disease. An ICS combined with a LABA is more effective than the individual components in improving lung function and health status, and reducing exacerbations, in patients with moderate to very severe COPD. And triple therapy with LABA+LAMA+ICS is more effective than LABA+ICS, LABA+LAMA or LAMA monotherapy.

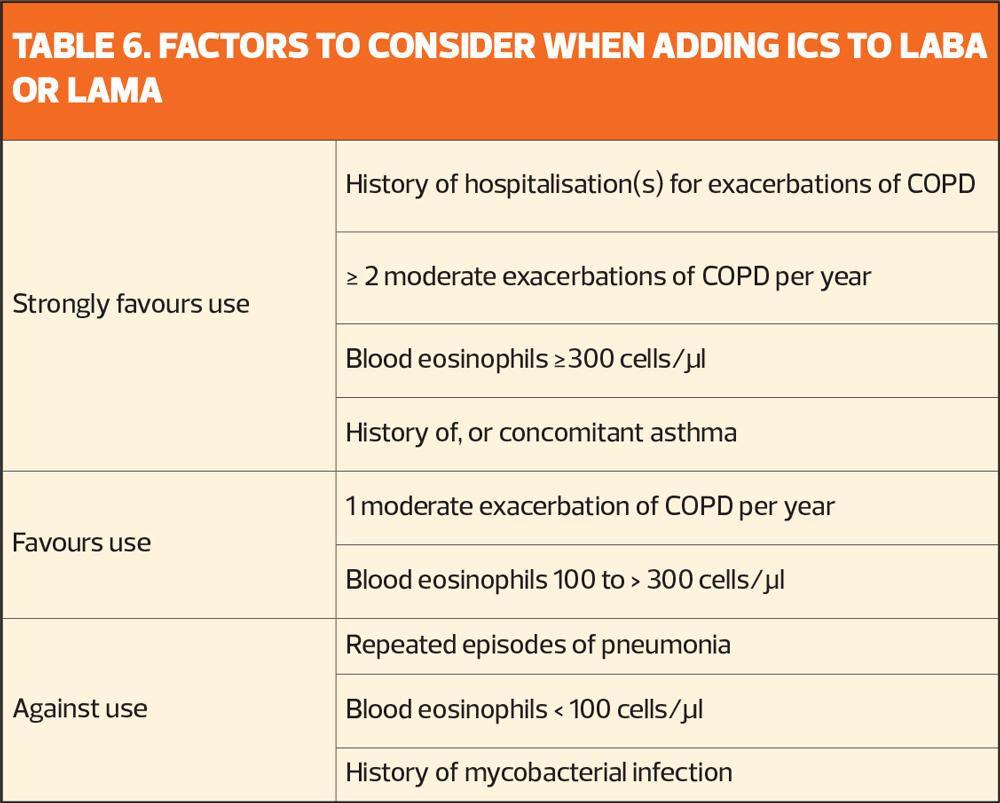

A number of studies have shown that blood eosinophil counts predict the efficacy of ICS (added to regular maintenance bronchodilator treatment) in preventing future exacerbations. No effect, or only a small effect, is seen when blood eosinophil count is <100 cells/μl, so this threshold can be used to identify patients who are unlikely to benefit from ICS, while those with a blood eosinophil count is ≥300 cells/μl are most likely to benefit (Table 6).

INHALED THERAPY

When treatment is given via inhaler, the importance of education and training in inhaler device technique cannot be overstated.

Worldwide, there are at least 33 different inhaled therapies — bronchodilators, short- or long-acting, and ICS, alone or in combination — and at least 22 different inhaler devices are available, including metered dose inhalers (with or without a spacer), breath-actuated inhalers, soft mist inhalers and dry powder inhalers, and nebulisers. They differ in size and portability, the number of steps needed to prepare them, in the force needed to load or actuate them, the time taken to deliver the drug, and in the need for cleaning, as well as the inspiratory effort needed to use them effectively. No device is available that avoids the need to explain, demonstrate and regularly check inhaler technique.

Selecting the optimum delivery system is essential to ensure that patients gain maximum benefit from their treatment: shared decision making has been shown to improve outcomes for patients with asthma, and is likely to do so for those with COPD.

Adherence

Adherence to inhaled medication is generally low, even in very severe disease. Factors such as the presence of comorbidities, especially depression, smoking status, education, disease severity and drug regimen (complexity and side effects) are the main causes of low adherence. Better patient understanding of their disease and medication can help to improve adherence, and behavioural approaches targeted to the individual's barriers (e.g. keeping medication in one place, self-monitoring symptoms, medication reminders) are more effective than offering general suggestions.

INITIATING TREATMENT

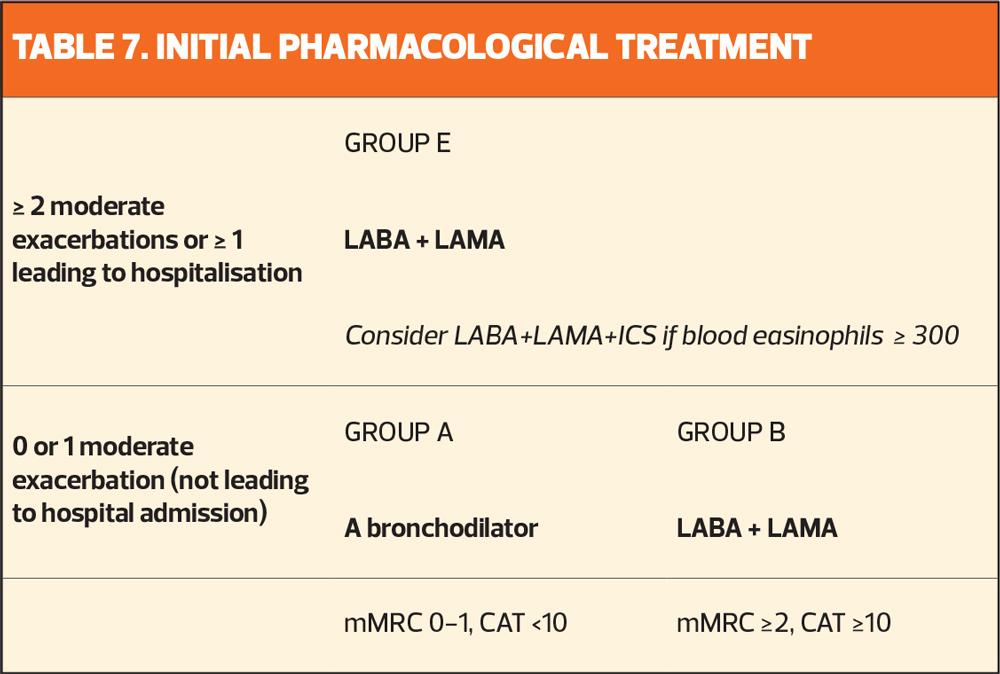

GOLD has proposed a new algorithm for the initiation of pharmacological treatment according to the individualised assessment of symptoms and exacerbation risk, following the ABE assessment scheme (Table 7).

All Group A patients should be offered a bronchodilator, based on its effect on breathlessness. This can be either a short- or long-acting bronchodilator, although a long-acting bronchodilator is preferred except in patients with only very occasional breathlessness.

Patients in Group B should be started on a LABA+LAMA combination. These patients are likely to have comorbidities that increase their symptom burden and can affect their prognosis, so these should be investigated and treated according to current guidelines.

Group E patients should also be offered a LABA+LAMA combination. If there is an indication for ICS, LABA+LAMA+ICS is the preferred treatment option. However, the effect of ICS on exacerbation prevention correlates with eosinophil count, so there is an argument for reserving this treatment option for patients with a high eosinophil count (≥ 300 cells/ μl).

Follow-up

After starting any treatment, patients should be reassessed for attainment of treatment goals and identification of any barriers to successful treatment, following which, adjustments to treatment may be needed. Follow up should comprise:

- Review: review symptoms (dyspnoea) and exacerbation risk (previous history, eosinophils)

- Assess: assess inhaler technique and adherence, and non-pharmacological strategies (smoking cessation, physical activity and pulmonary rehabilitation, vaccination)

- Adjust: adjust drug treatment, including escalation or de-escalation as indicated; switching inhaler device or using a different long-acting bronchodilator may be appropriate. Any change of treatment requires a subsequent review of clinical response.

SUMMARY

This Guidelline in a Nutshell aims to provide a summary of the main changes in the GOLD 2023 report that are relevant to general practice nurses.

These include a revised definition of COPD, updates to vaccine recommendations and a simplified assessment tool — the ABE assessment tool — to recognise the clinical relevance of exacerbations, independent of the level of symptoms. This is reflected in a new algorithm to guide the initial choice of pharmacological treatment.

However, the full guideline provides a wealth of detail and we would urge you to read it to develop your knowledge of COPD, and to help you improve the management of your COPD patients.

Reference

Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) 2023 Report. 2 December 2022. https://goldcopd.org/2023-gold-report-2/

Related guidelines

View all Guidelines