Guideline in a nutshell: New insights into COPD

Mandy Galloway

Mandy Galloway

Editor

Practice Nurse 2022;52(1):23-26

The annually-updated GOLD report on the management of chronic obstructive lung disease (COPD) offers new insights into the disease, treatment and the increased incidence of lung cancer in COPD patients

The aim of the Global initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) Report is to provide a non-biased review of the current evidence for the assessment, diagnosis and treatment of patients with COPD.

A major strength of GOLD reports is the treatment objectives, which are grouped into short- and long-term goals, namely the relief and reduction of symptoms and reducing the risk of future exacerbations. These have withstood the test of time since the first edition was published, in 2001. Back then, assessment of symptoms did not have a direct relationship with the choice of treatment and health status was only measured in clinical studies. Now there are simple questionnaires for use in daily practice that consider both the impact of symptoms and the risk of serious adverse health events, and this approach has helped to move COPD towards individualised medicine, matching the patients’ treatment more closely to their individual needs.

The 2022 report from GOLD builds on these objectives, and introduces new definitions for stages of COPD, and clarifies what is often described as ‘mild’ COPD; provides more information on symptoms and pharmacotherapy; and importantly, adds new recommendations on screening for lung cancer in patients with COPD.

INFLUENCES ON DISEASE PROGRESSION

Cigarette smoking is the most well studied COPD risk factor but it is not the only one, and non-smokers may also develop chronic airflow limitation. Nevertheless, never smokers with chronic airflow limitation have fewer symptoms, milder disease and lower burden of systemic inflammation. These patients do not appear to have increased risk of lung cancer or cardiovascular comorbidities, compared with those without chronic airflow limitation – although they are at higher risk of pneumonia and respiratory failure.

COPD results from a complex combination of genes and the environment. The risk factor that we know most about is a severe hereditary deficiency of alpha-1 antitrypsin (AATD), which predisposes individuals to COPD. A significant familial risk of airflow limitation has also been noted between people who smoke and are siblings of patients with COPD.

Processes during gestation, birth and exposures during childhood and adolescence affect lung growth, and reduced maximal attained lung function (as measured by spirometry) may identify people at increase risk of developing COPD. Recent research shows that COPD can result from reduced peak lung function in early adulthood or accelerated lung function decline. These factors provide new opportunities for prevention, earlier diagnosis and treatment, but also create a need for new definitions.

New definitions

- Early COPD. Early means ‘near the beginning of a process’. COPD can start early in life and take a long time to manifest clinically, meaning that it is difficult to identify. Biological ‘early’ means the initial mechanisms that eventually lead to COPD and is not the same as clinically early, which is the initial perception of symptoms or functional limitation. GOLD therefore recommends that ‘early COPD’ should only be used to describe biologically early.

- Mild COPD. Some studies have used ‘mild’ airflow limitation to describe early disease. This assumption is incorrect because not all patients start their journey from normal peak lung function in early adulthood – so some of them may never suffer ‘mild’ disease in terms of severity of airflow limitation. ‘Mild’ disease may occur at any age and may or may not progress. GOLD therefore recommends that ‘mild’ should not be used to identify early COPD.

- COPD in young people. This term relates directly to the chronological age of the patient. Lung function peaks at around 20-25 years, so GOLD recommends using this term for patients in the 20-50 year age range. This may include people who never achieved normal peak lung function in early adulthood, and those with early accelerated lung function decline. COPD in young people may have a substantial impact on health, and is frequently not diagnosed or treated, although there may be significant structural and functional abnormalities. A family history of respiratory diseases and/or hospitalisations before the age of 5 is reported by a significant proportion of young people with COPD.

- Pre-COPD. This term has been suggested to identify individuals of any age who have respiratory symptoms with or without detectable structural and/or functional abnormalities but no airflow limitation, and who may (or may not) develop COPD over time.

Occupational exposures

Occupational exposure to organic and inorganic dusts, chemical agents and fumes are an under-appreciated risk factor for COPD. People who are exposed to inhalation of high doses of pesticides have a higher incidence of respiratory symptoms, airways obstruction and COPD. A UK-based population study identified occupations (including sculptors, gardeners and warehouse workers) that were associated with a higher risk of COPD risk among never-smokers and people who had never had asthma. Occupational exposures are thought to account for 10-20% of either symptoms or functional impairment consistent with COPD.

While the role of air pollution as a general risk factor for COPD is unclear, there is evidence of a significant association between ambient levels of particulate matter and the incidence of COPD, as well as reduced lung function in children.

SYMPTOMS

Although COPD is defined on the basis of airflow limitation, in practice a patient’s decision to seek medical help is usually because of the impact of symptoms on their daily lives. They may consult their GP or GPN either because of chronic respiratory symptoms or because of an acute episode of exacerbated respiratory symptoms.

- Breathlessness (dyspnoea) is a cardinal symptom of COPD and is a major cause of disability and anxiety.

- Cough is often the first symptom of COPD but may be dismissed by the patient as an expected result of smoking and/or environmental exposures. Initially, the cough may be intermittent but subsequently may occur every day, often throughout the day, and it may be productive or unproductive. Notably, significant airflow limitation may develop in the absence of a cough.

- Sputum production: COPD patients commonly produce small quantities of sticky sputum with coughing. Sputum production is often difficult to evaluate because patients may swallow sputum rather than expectorating it. The presence of purulent sputum reflects an increase in inflammatory mediators and may, but not necessarily, identify the onset of a bacterial exacerbation.

- Wheezing and chest tightness are symptoms that may vary from day to day and over the course of the day. Audible wheeze may occur at the laryngeal level but may not be heard on auscultation – but alternatively, widespread inspiratory or expiratory wheezes may be present on auscultation. Chest tightness often follows exertion. An absence of wheezing or chest tightness does not exclude a diagnosis of COPD, nor does their presence confirm a diagnosis of asthma.

- Fatigue is recognised in the 2022 report as a symptom of COPD. Fatigue is the subjective feeling of tiredness or exhaustion, and is one of the most common symptoms experienced by patients with COPD. It can affect both the patient’s abilities to carry out activities of daily living and their quality of life.

Additional features in severe disease include weight loss, muscle loss and anorexia. They are important prognostic factors, and can also be a sign of other diseases, such as tuberculosis or lung cancer, so should always be investigated.

PHARMACOTHERAPY

Pharmacological therapy for COPD is used to reduce symptoms, reduce the frequency and severity of exacerbations, and improve exercise tolerance and health status.

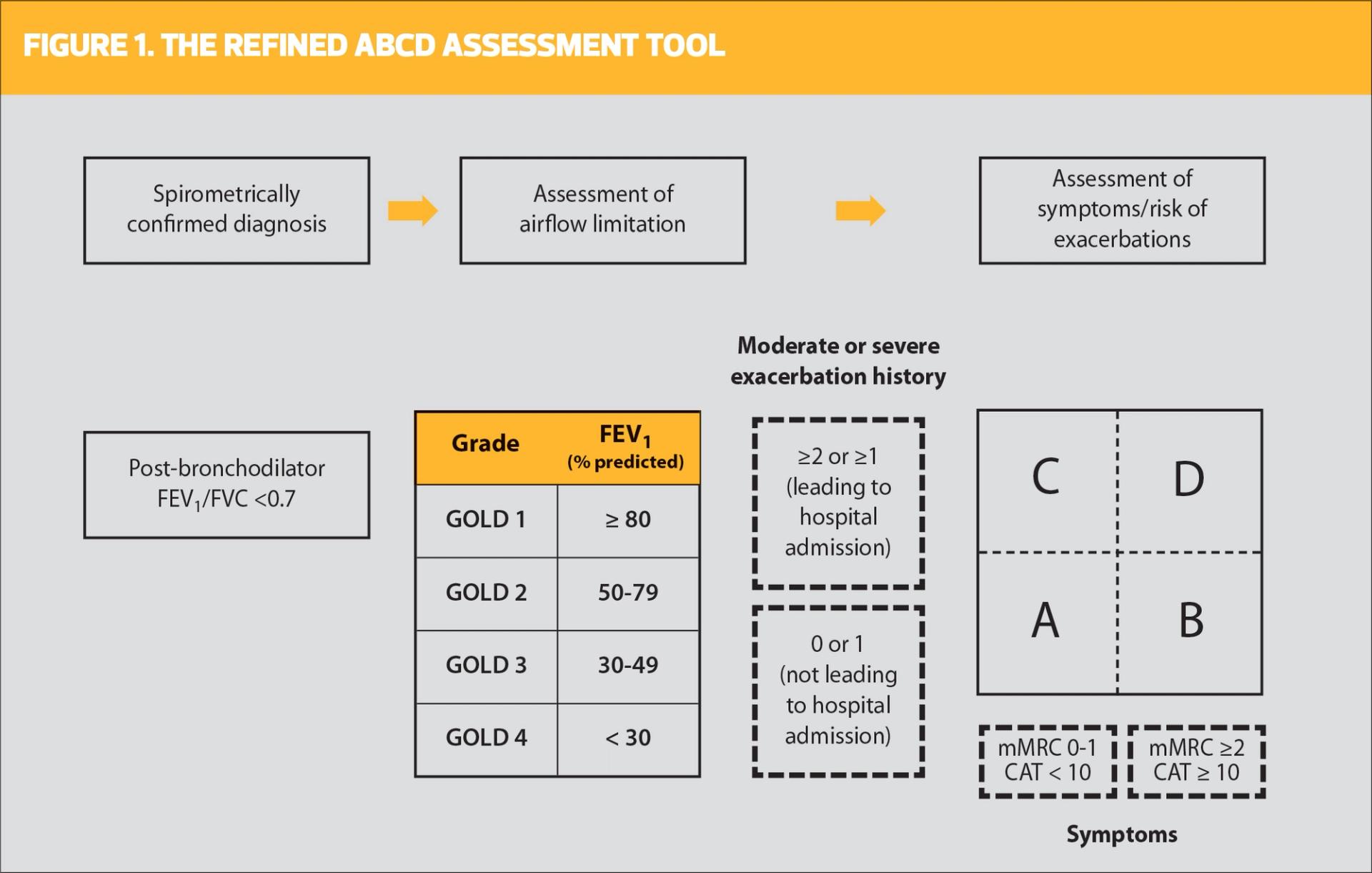

Individual decisions on treatment should be based on the ABCD assessment (Figure 1). This can help to identify patients who would benefit particular treatment approaches, based on their spirometry results, the assessment of airflow limitation, their symptoms and exacerbation risk/ history.

Bronchodilators are the cornerstone of therapy in COPD, and combining bronchodilators with different mechanisms and durations of action may increase the degree of bronchodilation with a lower risk of side effects compared with increasing the dose of a single agent. Combinations of short-acting beta2 agonists (SABA) and short-acting antimuscarinics (SAMA) are superior to either medication alone in improving FEV1 and symptoms. Similarly, a combination of long-acting beta2 agonists (LABA) and long-acting antimuscarinics (LAMA) improves lung function and the improvement is consistently greater than with long-acting bronchodilator monotherapy. Symptom responses to LABA/LAMA combinations may vary between individual patients, and should be evaluated on an individual basis. Combination therapy also reduces exacerbations compared with monotherapy.

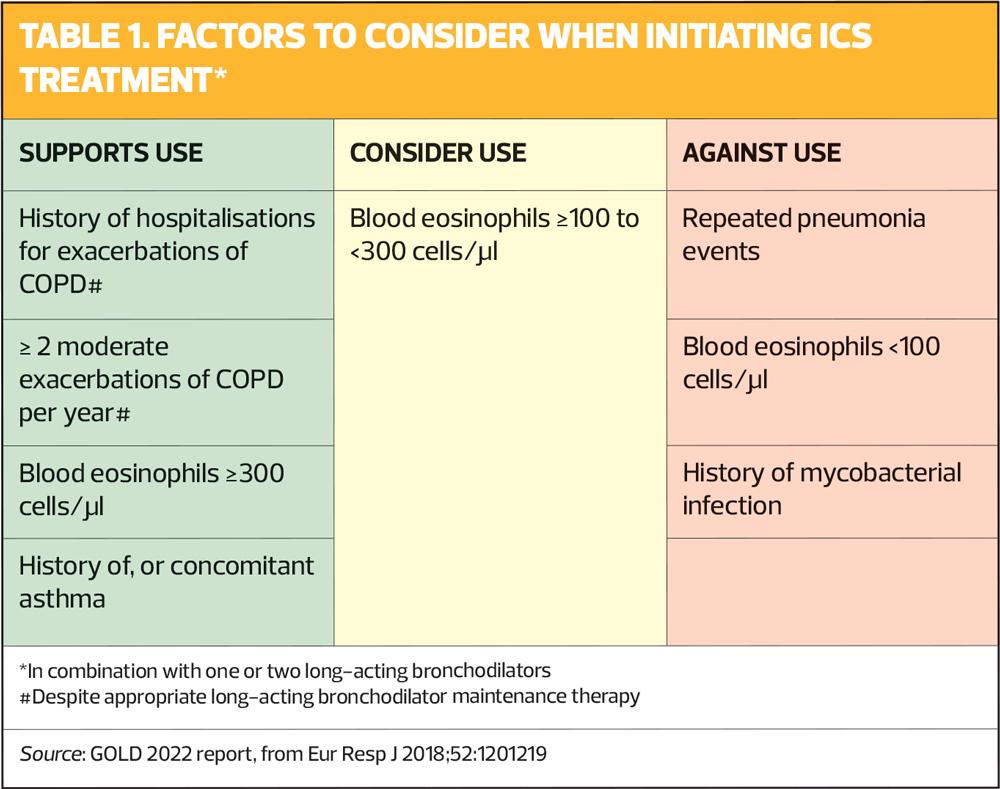

Adding an inhaled corticosteroid (ICS) to long-acting bronchodilator therapy in patients with moderate to very severe COPD and a history of exacerbations has been shown to be more effective than either component alone in improving lung function, health status and reducing exacerbations. However, regular treatment with ICS increases the risk of pneumonia, especially in those with severe disease.

A number of studies have shown that blood eosinophil counts predict the magnitude of the effect of ICS (added to regular maintenance bronchodilator treatment) in preventing future exacerbations. There is a continuous relationship between blood eosinophil counts and ICS effects – at low counts, ICS has little or no effect. The threshold of a blood eosinophil count ≥300 cells/μl can be used to identify patients with the greatest likelihood of benefit from ICS treatment, but should always be used in combination with clinical assessment of exacerbation risk, as indicated by the previous history of exacerbations – see Table 1.

Inhaler technique

When prescribing an inhaler for patients with COPD, it is essential to ensure that patients have been trained to use the proposed device. Studies have shown a significant relationship between poor inhaler technique and symptom control in patients with COPD (as in patients with asthma). Factors related to poor technique include older age, use of multiple devices and lack of education on inhaler technique. This can be improved by asking patients to show how they use their device. It is also important to check that patients continue to use their device correctly – ask them to bring their own inhaler(s) to review appointments. Assess technique and adherence before concluding that the patient’s current therapy is insufficient.

COPD AND COMORBIDITIES

COPD often coexists with other diseases that can have a significant impact on the patient’s prognosis. Some of these comorbidities can occur independently of COPD, others may be causally related, either with shared risk factors or by one disease increasing the severity of the other. Comorbidities are common at any severity of COPD, and the differential diagnosis can often be difficult.

Lung cancer is frequently seen in patients with COPD and is a major cause of death. There is strong evidence for an association between COPD and lung cancer, and these two diseases appear to share more than tobacco exposure as their common origin. Genetic susceptibility, local pulmonary inflammation and abnormal lung repair mechanisms present in COPD are also thought to be important contributors to the development of lung cancer. The association between lung cancer and the degree of emphysema (diagnosed by CT) is stronger than that between lung cancer and the degree of airflow obstruction.

GOLD therefore recommends annual low-dose CT scan for lung cancer screening in patients with COPD due to smoking. Annual screening is not recommended for patients with COPD not due to smoking, because there are insufficient data to establish benefit over harm. GOLD warns that screening could be useful, but should be implemented appropriately to avoid overdiagnosis, greater morbidity and mortality with needless diagnostic procedures for benign abnormalities, anxiety and incomplete follow up, as has been suggested by studies in primary care.

There is controversy over whether or not there is an association between ICS-treatment and lung cancer, with conflicting results between observational studies and randomised controlled trials.

COPD AND COVID-19

As general practice nurses will be aware, the COVID-19 pandemic has made routine management and diagnosis of COPD more difficult, as a result of reductions in face-to-face consultations, difficulties in performing spirometry and limitations in traditional pulmonary rehabilitation and home care.

Despite the number of rapid publications on the SARS-CoV-2 virus and the pandemic, it not yet known definitively whether having COPD affects the risk of becoming infected with COVID-19, but based on current evidence it appears that patients with COPD do not seem to be at greatly increased risk. However, they may be at greater risk of hospitalisation, severe disease and death if they do become infected. Furthermore, coronaviruses are among the respiratory viruses that trigger COPD exacerbations. This makes it even more important that patients with COPD should have COVID-19 vaccination, in line with national recommendations.

The report also contains a check-list for remote consultations and follow-up of patients with COPD, which will be helpful considering the current prevalence of the omicron variant. See also Guidelines in a nutshell: The 2021 GOLD report Practice Nurse 2020;50(10):23-25.

CONCLUSION

This article is intended to provide a summary of changes in the latest GOLD report, to help GPNs stay up-to-date with the latest evidence-based management considerations. GOLD reports are updated annually, whereas the most recent guideline from NICE, published in 2018, has not been updated since July 2019 – although there has been a rapid COVID-19 guideline on patients with COPD and suspected and confirmed COVID-19.

The 2022 report does not constitute a major revision of previous editions, but does contain important new advice, and further evidence for existing recommendations. For anyone who is new to managing COPD, or would benefit from a refresher on the basics of this common condition, we would urge you to read the Pocket Guide or, better still, the full report, both available at https://goldcopd.org/2022-gold-reports-2/, where you will also find a teaching slide set.

Related guidelines

View all Guidelines