Needle know-how: injection technique in clinical practice and patient education

Alys Bunce RGN, BSc Nursing, BSc Psych, PGCE

Practice Nurse 2025;55(4):9-12

Injection technique is a core clinical skill—one that blends anatomical knowledge with practical dexterity and patient rapport. Whether administering a vaccine or teaching a patient to self-inject, the clinician’s approach directly impacts both the effectiveness of treatment and the patient’s experience

This article is part of a series revisiting basic nursing skills and follows our previous article issue focusing on the basics of phlebotomy.1 Though different in purpose, both require precision, confidence, and an understanding of how to work with—not on—the patient. In this article, we’ll explore the practical aspects of subcutaneous (SC) and intramuscular (IM) injections, briefly touch on intradermal (ID) and intravenous (IV) techniques, and consider the growing need to teach self-injection to patients. From GLP-1 receptor agonists to anticoagulants, more people than ever are learning to manage their care at home,2-4 and clinicians need to ensure they are doing it safely.

INJECTION TYPES AND THEIR RELEVANCE

Subcutaneous (SC) Injections

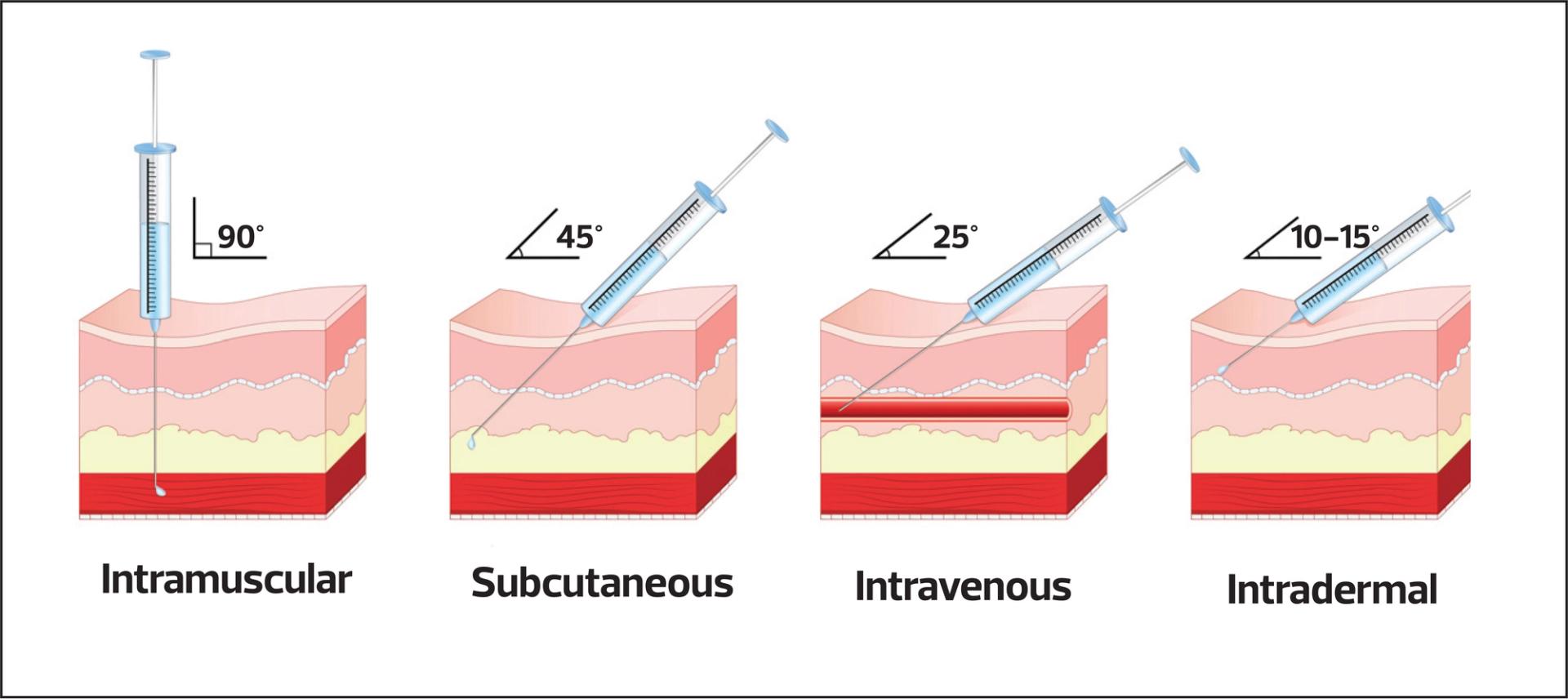

SC injections deliver medication into the fatty tissue just beneath the skin.5 The needle is inserted at a 45–90° angle, depending on the patient’s body habitus and needle length. A skin pinch is often used to separate fat from underlying muscle. Recommended maximum volume is typically 1ml.

The most common examples in general practice include insulin, low molecular weight heparin (e.g., enoxaparin), and GLP-1 receptor agonists such as semaglutide (Ozempic). Some vaccines are also administered SC. This results in slower absorption and prolonged antigen exposure, which can enhance immune responses in vaccines designed for this route, such as certain live attenuated vaccines (e.g., varicella, yellow fever, dengue).5 SC administration is also sometimes preferred for individuals with bleeding disorders, or those on anticoagulants to reduce the risk of heamatoma.5 It is relatively easy to perform a SC injection, making it a good candidate for self-administration (e.g., insulin).6

However, potential issues include lipohypertrophy from repeated injections in the same area, bruising, and poor absorption if the technique or site is incorrect.7 Lipohypertrophy can affect both insulin therapy (leading to variable absorption rates) and other SC treatments.6 For patients who are self-administering, it is important to educate them about site rotation to prevent tissue damage and maintain consistent treatment outcomes.6,7

Intramuscular (IM) Injections

Intramuscular injections are used for medications requiring rapid or sustained absorption due to the muscle’s rich blood supply, which facilitates efficient drug uptake.5 Vaccines including tetanus, hepatitis B and rabies rely on deep muscle delivery to elicit an effective immune response. Intramuscular injections are faster than SC injections in terms of absorption and are often preferred when a quicker therapeutic effect is needed, such as when adrenaline is being given. Muscles can accommodate larger volumes than subcutaneous tissue, making IM suitable for higher-dose medications and vaccines. IM technique is often used for vaccines, B12, and depot contraception injections.8 Certain formulations that may irritate fatty tissue are also better tolerated in muscle, reducing the risk of local reactions or necrosis. IM administration also offers consistent absorption and, in some cases – such as depot injections – enables slow, controlled release over time.

IM injections require careful attention to site selection and needle size to avoid complications such as shoulder injuries. The Green Book ‘Immunisation against infectious diseases’ (Chapter 4) specifies that the deltoid muscle is preferred for most adult vaccinations and if muscle mass is insufficient, the anterolateral thigh may be used.5 In children under 12 months old, the thigh is the preferred choice. The gluteal region is generally avoided for vaccines due to variable fat depth and potential reduced immunogenicity.

Technique points from the Green Book 5:

- Use a 25mm needle (23G or 25G) for most adults; longer needles may be needed for higher BMI.

- Insert at 90° into relaxed muscle. Stretch the skin (unlike SC where the skin is often bunched)

- Aspiration is not recommended for vaccines, unless specified in the summary of product characteristics (SmPC).

- Maximum IM injection volume in adults is usually up to 5ml, although most vaccines require much less.

Intradermal (ID) Injections

Intradermal (ID) injections deliver vaccines into the dermis, a skin layer rich in specialised immune cells like Langerhans and dendritic cells, which can elicit a potent immune response, even with a smaller dose. This dose-sparing advantage makes ID administration particularly valuable during vaccine shortages (e.g., rabies, mpox) and in low-resource settings due to its cost-effectiveness.9 Some vaccines are specifically designed for ID use, such as the BCG vaccine, to maximise immunogenicity.10 Additionally, the ID route can be beneficial for individuals with limited muscle mass or bleeding disorders, where intramuscular injection may be unsuitable.

However, ID administration requires a high degree of precision to ensure accurate placement within the dermis, as incorrect technique can reduce efficacy or cause local adverse reactions. This is generally not a route that a patient would be taught to administer themselves, and it is not even a particularly common route delivered by health professionals in primary care. ID injections are also important in identifying specific conditions such as tuberculosis exposure (Mantoux testing). Their technique is highly sensitive, and incorrect placement can lead to inaccurate test results, making training and experience essential for healthcare professionals.10

The Green Book (Chapter 32 – TB) recommends a short, fine needle (26G or 27G) and injection at a shallow 10–15° angle. The goal is to create a visible bleb just under the surface of the skin.10

Intravenous (IV) Injections

While, again, not routine in most GP settings, IV access may be relevant in substance misuse clinics, emergency care, or community settings. IV technique overlaps with phlebotomy but requires additional training and local governance.11

Regardless of the route, good technique is grounded in preparation, confidence, and patient-centred care.

BEST PRACTICE IN CLINICAL TECHNIQUE

Key steps5,12

Site selection: Use clear anatomical landmarks. Avoid areas with inflammation, scarring, or poor circulation. Take extra care around areas that have a rich blood or nerve supply (such as gluteal administrations) or near joints (such as the shoulder). Avoid injecting on the same side as a mastectomy or lymph gland removal.

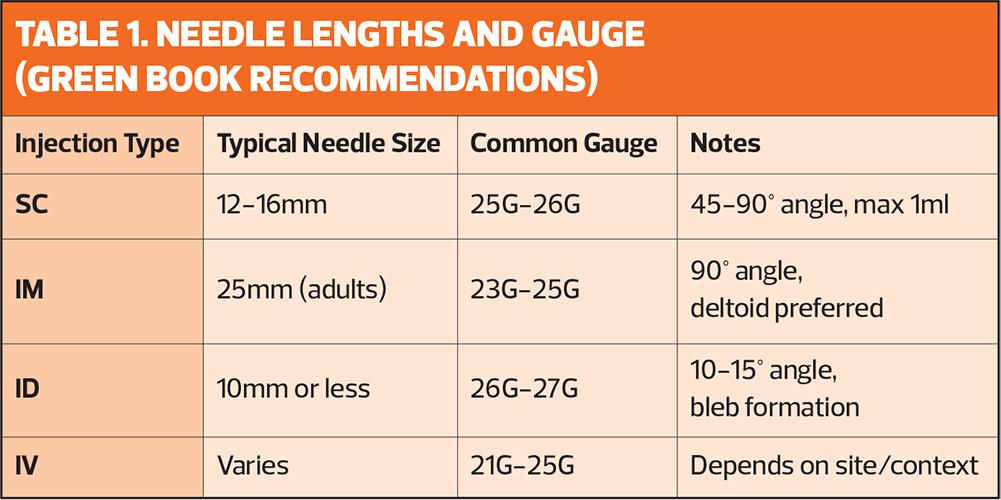

Needle choice: Base selection on the route, medication viscosity, site, and patient build. See Table 1 for common needle lengths and gauges.

Skin preparation: The Green Book advises that visibly clean skin does not require alcohol swabbing (for further detail, see Alcohol swabs and intramuscular injections: where do we stand? Practice Nurse, January/February 2025).13 If cleansing is needed, use soap and water and allow to dry fully. Note that phlebotomy guidance on skin cleansing differs – see Best practice in phlebotomy, Practice Nurse, March/April 2025.1

Patient comfort: Use verbal reassurance, distraction techniques, and allow the patient to ask questions. A relaxed patient improves accuracy and reduces pain.

Aftercare: Immediate disposal of sharps into approved containers 14. Observe for immediate reactions and advise on common side effects.

Documentation: Should include all medication details, site/route, date/time, any adverse events, and practitioner details. Informed consent being gained is also an important documentation point.

CHALLENGES AND CONTROVERSIES

Injection technique is not without its grey areas. Some key debates and concerns include:

- Aspiration: Still taught in some settings and for certain anatomical sites or drugs, but is not recommended by the Green Book for vaccines. Always consult the SmPC for each individual product.

- Misinformation: Social media trends, particularly with GLP-1 agonists,15 lead to unsupervised use. Clinicians should be prepared to offer harm reduction advice, even when patients have sourced medication privately.

- Access and training gaps: Not all staff receive adequate practical training, particularly for less common routes such as ID, or for specific medicines where a generalised technique may not be applicable for that particular drug.

- Cultural and psychological barriers: Needle fear, drug hesitancy, modesty, and stigma can all impact a patient’s willingness to inject or be injected.16 Empathy and adaptability are essential. See Vaccine hesitancy: a growing concern in this issue.

INJECTION TECHNIQUE AS A TEACHABLE SKILL

Injection technique is a learned skill. Developing this ability can be empowering for clinicians and patients alike. For nurses and healthcare assistants, it is a valuable part of clinical progression and can lead to educator roles.

Training tools might include:

- Injection pads and simulators

- Manufacturer demo kits

- Peer observation and mentorship

- Reflective practice and CPD logs

- Competency tools and checklists

Embedding good technique into standard operating procedures and local competency frameworks ensures safer practice and supports ongoing quality improvement.17,18

TEACHING INJECTION TECHNIQUE TO PATIENTS

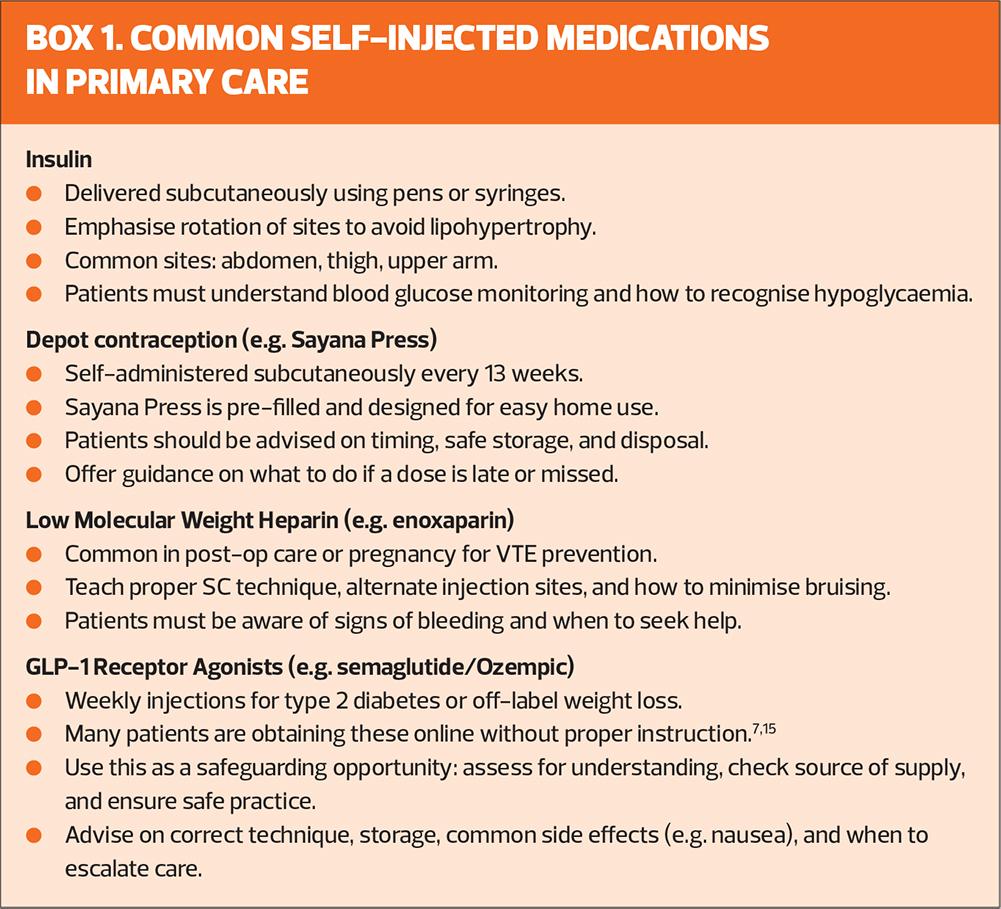

As more medications are designed for self-administration (see Box 1), clinicians must take on the role of educator, ensuring safety, confidence, and adherence to treatment. There are numerous patient materials available to assist both clinicians and patients in this teaching process.

Principles of Teaching Self-Injection

The teaching process should be patient-centred, with time for questions, demonstration, and return demonstration. A helpful structure is:

- Explain – Why the injection is needed, why it is administered the way it is, what it does, and how often it must be given.

- Demonstrate – Use a practice device or empty syringe to show the correct technique. Or do the first administration on the patient yourself to demonstrate how it works.

- Observe – Let the patient try it while you supervise.

- Reinforce – Offer written and visual materials, links to approved videos (e.g., NHS or manufacturer resources), and repeat training if needed. Keep checking in to make sure no deviations in technique or complications have occurred over time.

Emphasise storage, safe disposal, side effect monitoring, and when to seek help.14,19 Emphasise the importance of compliance with the prescribed treatment schedule to avoid complications such as clot formation with anticoagulants, or potential non-responsiveness to GLP-1 receptor agonists.7,3,20

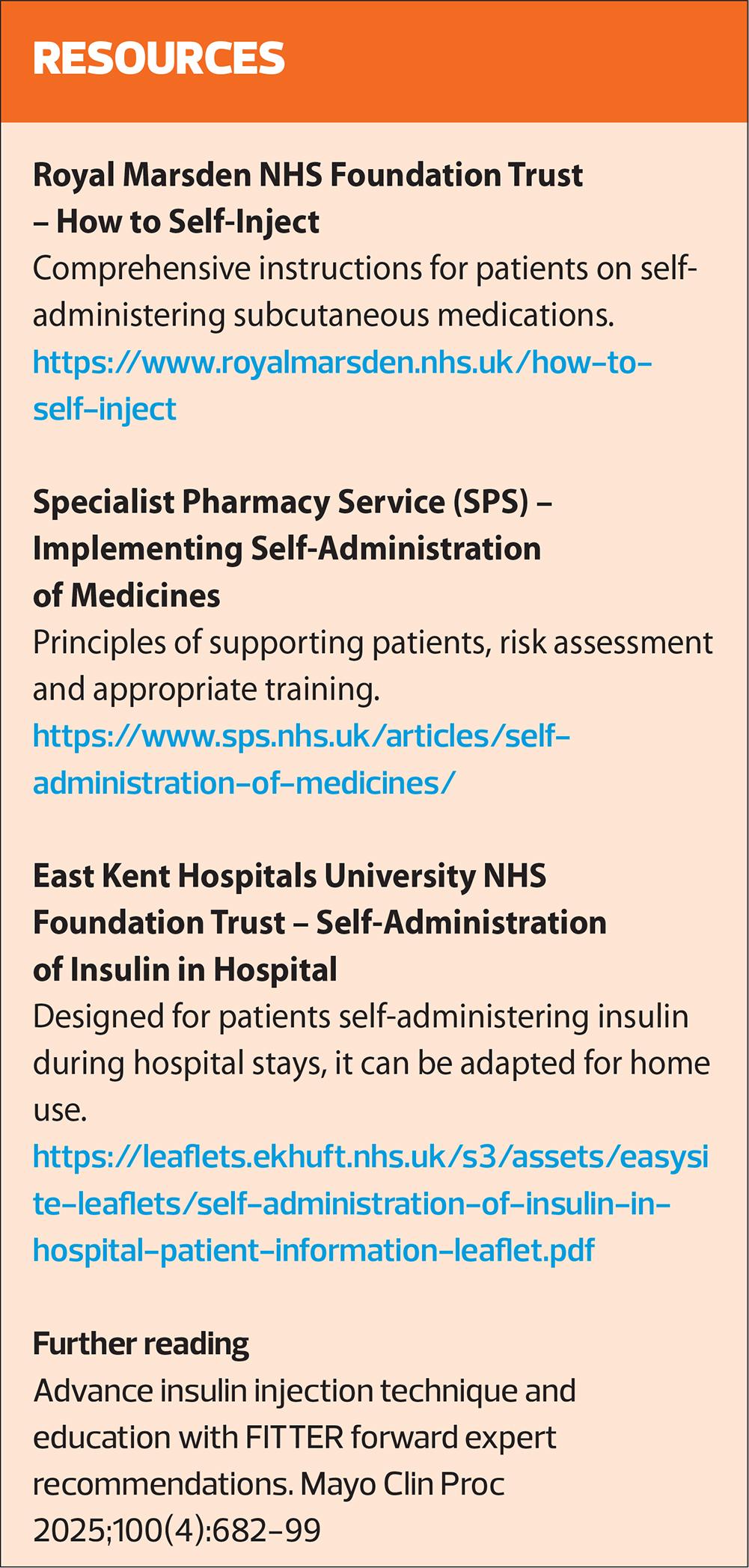

Patient education resources can further enhance the patient’s learning experience. For example, East Kent Hospitals University NHS Foundation Trust provides clear and accessible materials on insulin injection techniques, while the Specialist Pharmacy Service (SPS) offers structured guides for healthcare professionals on teaching self-administration of medicines.18,21 See Resources for links and further examples of training materials.

Teaching patients how to self-inject involves a mix of direct instruction and empowering the patient to manage their own care.

Challenges and nuances

Teaching patients to administer their own injections, while empowering, poses challenges and risks. Ensuring that the patient understands and performs the technique correctly is crucial for preventing complications such as injection site reactions, medication errors, and improper technique.17 The NICE guideline on diabetes management (NG28) emphasises the importance of patient education to promote adherence and improve outcomes but also points out that some patients may require more frequent support to master these skills.6

The ability of patients to perform injections effectively can vary based on several factors, including cognitive ability, physical dexterity, and emotional readiness. Psychological factors, such as fear of needles or anxiety about self-injection, may impact adherence.16,22,23 Moreover, not all patients have the same access to training resources or healthcare professionals to support them. As such, clinicians must be mindful of individual needs and provide tailored teaching strategies, which may involve additional time, follow-up appointments, and reinforcement.

Another key issue is patient adherence – studies show that even with adequate training, patients may fail to inject on time or skip doses altogether.6 This non-adherence can affect therapeutic outcomes, particularly with chronic conditions requiring consistent treatment, such as diabetes or anticoagulant therapy. Furthermore, health literacy can be a barrier.23 Patients with limited knowledge or comprehension of medical terms or injection techniques may struggle with self-injection, which could result in incorrect administration or missed doses.

Clinicians must also consider the psychological impact of self-injection. For many patients, injecting medication themselves can be anxiety-inducing.16 Offering reassurance and allowing time for questions can help alleviate this fear. However, some patients, particularly those with needle phobia or those new to injections, may require additional psychological support or a more tailored approach.6

However, well-designed educational materials and proper support can help to overcome these barriers. The use of patient-friendly resources can empower patients to manage their own healthcare effectively, improving both their confidence and treatment outcomes.

IN SUMMARY

Injection technique is more than just a motor skill – it’s an opportunity to connect with patients, ensure safe medication delivery, and empower self-management. In a healthcare landscape where more treatments are moving into the community, clinicians must combine technical accuracy with teaching and reassurance.

Whether you are administering an injectable medicine, training up a new member of staff, or teaching a patient to self-inject, your knowledge and confidence make all the difference. Keep reflecting, stay up to date, and never underestimate the power of a well-placed needle.

REFERENCES

- Bunce A. Best practice in phlebotomy. Practice Nurse 2025;55(2):9-13.

- Novo Nordisk. Ozempic 1 mg solution for injection in pre-filled pen: summary of product characteristics; 2024. https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/product/9584

- Oxford University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust. Enoxaparin (Clexane): how to self-inject. 2020. https://www.ouh.nhs.uk/patient-guide/leaflets/files/16290Penoxaparin.pdf

- Royal Pharmaceutical Society. Injectable Medicines Guide: Enoxaparin; 2021.

https://www.rpharms.com/resources/quick-reference-guides/injectable-medicines-guides - UK Health Security Agency. Immunisation against infectious disease: the Green Book, Chapter 4 – Immunisation procedures; 2013

https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/immunisation-schedule-the-green-book-chapter-11 - NICE NG28. Type 2 diabetes in adults: management; 2022. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng28

- Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA). Self-administration of Medicines: Safety and Advice; 2024 https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/self-administration-of-medicines-safety-and-advice

- Faculty of Sexual and Reproductive Healthcare (FSRH). FSRH Clinical Guideline: Injectable Contraception; 2020. https://www.fsrh.org/standards-and-guidance/current-clinical-guidance/injectables/

- World Health Organization. Intradermal delivery of vaccines: a review of the literature and the potential for development for use in low- and middle-income countries; 2009. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/70102

- UK Health Security Agency. Immunisation against infectious disease: the Green Book, Chapter 32 – Tuberculosis; 2018. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/tuberculosis-the-green-book-chapter-32

- Royal College of Nursing. Standards for Infusion Therapy; 2021. https://www.rcn.org.uk/professional-development/publications/pub-009936

- Dougherty L, Lister S, eds. The Royal Marsden Manual of Clinical Nursing Procedures. 9th ed. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell; 2015.

- Bunce A. Alcohol swabs and intramuscular injections: where do we stand? Practice Nurse 2025;55(1):8-11.

- Specialist Pharmacy Service. Safe disposal of sharps – advice for healthcare professionals; 2023. https://www.sps.nhs.uk/articles/safe-disposal-of-sharps/

- Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA). GLP-1 receptor agonists (including semaglutide and liraglutide): risk of misuse, off-label use, and serious side effects. Drug Safety Update; 2024.

https://www.gov.uk/drug-safety-update/glp-1-receptor-agonists-including-semaglutide-and-liraglutide-risk-of-misuse-off-label-use-and-serious-side-effects - McLenon J, Rogers MAM. The fear of needles: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Adv Nurs 2019;75(1):30–42. https://doi.org/10.1111/jan.13818

- Royal Marsden NHS Foundation Trust. How to self-inject. https://www.royalmarsden.nhs.uk/how-to-self-inject

- Specialist Pharmacy Service. Implementing self-administration of medicines. https://www.sps.nhs.uk/articles/implementating-self-administration-of-medicines/

- Royal Cornwall Hospitals NHS Trust. Self-administration of subcutaneous systemic anti-cancer therapies (SACT) policy. https://doclibrary-rcht.cornwall.nhs.uk/GET/d10361452

- Guy’s and St Thomas’ NHS Foundation Trust. Self-injecting with enoxaparin (Clexane); 2020.

https://www.guysandstthomas.nhs.uk/resources/patient-information/pharmacy/self-injecting-with-enoxaparin.pdf - East Kent Hospitals University NHS Foundation Trust. Self-administration of insulin in hospital: patient information leaflet. https://leaflets.ekhuft.nhs.uk/s3/assets/easysite-leaflets/self-administration-of-insulin-in-hospital-patient-information-leaflet.pdf

- Polonsky WH, Henry RR. Poor medication adherence in type 2 diabetes: recognizing the scope of the problem and its key contributors. Patient Prefer Adherence 2016;10:1299–1307. https://doi.org/10.2147/PPA.S106821

- Bailey SC, Brega AG, Crutchfield TM, et al. Update on health literacy and diabetes. Diabetes Educ 2014;40(5):581–604. https://doi.org/10.1177/0145721714540220

Related articles

View all Articles