Management of bedwetting

This resource has been initiated, supported and reviewed solely by ALTURiX Ltd. The content has been developed by Practice Nurse.

INTRODUCTION

Bedwetting – nocturnal enuresis – is a common disorder that can have a significant impact on a child’s school performance, social and psychological function, and quality of life both for the child and their parents or carers.1

Once considered a problem that the child would simply grow out of, it is a treatable condition, and general practice nurses should provide accurate and timely advice and intervention when it is reported.

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

On completion of this module, you will be more familiar with:

- The definition, prevalence and natural progression of enuresis

- The impact on children and families

- The causes of bedwetting and common comorbidities

- The treatment of bedwetting

This resource is provided at an intermediate level. Read the article and answer the self-assessment questions, and reflect on what you have learned.

Complete the resource to obtain a certificate to include in your revalidation portfolio. You should record the time spent on this resource in your CPD log.

PRACTICE NURSE FEATURED ARTICLE

Richardson D. Bedwetting: a guide for practice nurses. Practice Nurse September-October 2023;53(5)

Job code: DM 030

Date of preparation: October 2023

This article has been initiated and supported and reviewed solely by ALTURiX https://alturix.com/

Prescribing information for DEMOVO® is available here.

Reporting adverse effects: Adverse events should be reported. Reporting forms and information can be founds at https://yellowcard.mhra.gov.uk

Contents

The management of bedwetting

Bedwetting, nocturnal enuresis or simply enuresis, is a medical condition of ‘intermittent incontinence that occurs during periods of sleep, once a month or more frequently, for at least three months, in children aged over five years’.2

It affects about 5–10% of seven-year-olds and 3% of teenagers.3 Numbers reduce with increasing age. However, prevalence continues at about 2% in adulthood. Those who are wetting most frequently can be assumed to have the most significant and enduring negative impacts and are known to be least likely to experience spontaneous resolution of symptoms.4

In children, bedwetting can cause a sense of shame, social stigma and fear of bullying, resulting in children feeling ‘different’ and socially isolated.5 Young adults may choose social isolation and avoid intimate relationships to avoid disclosing their enuresis.6

Associated stress for parents may be one of the reasons why some respond punitively to their children, by scolding, discipline, sleep deprivation and corporal punishment,1 despite this being an unhelpful response that may increase wetting.7

CAUSES

Bedwetting is known to run in families. However, genetic links do not indicate the causes for the individual, duration of the condition or response to treatment.8 NICE9 describes bedwetting as ‘a symptom that may result from a combination of different predisposing factors.’ The three systems model of enuresis remains an accepted description of enuresis, which outlines the main causes: nocturnal polyuria, and/or bladder overactivity during sleep, combined with an inability to wake to bladder signals.10

Children with bedwetting have disturbed sleep associated with poorer quality of life, and treatment improves neuropsychological functioning.11,12

There are several comorbidities that are associated with enuresis, and enuresis is occasionally a symptom of other conditions. Sudden onset of bedwetting after a period of being dry should be investigated and underlying pathology including diabetes mellitus, urinary tract infection and polyuric renal failure should be excluded.3

Children with developmental differences including autism and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder are more likely to have enuresis than children with typical development and are more likely to be resistant to treatment.13,14

Constipation is also associated with enuresis.15 The rationale is that the retained stools distend the rectum causing pressure on the bladder. They may also trigger detrusor overactivity, which may produce daytime symptoms, including frequency, urgency and daytime urinary incontinence.16 Constipation and daytime lower urinary tract symptoms should be assessed and treated, although their absence does not exclude the latter problem occurring only during sleep.

If present, sleep disordered breathing produces frequent arousal stimuli from the upper airways, making the child less able to wake to bladder signals. Resolution of the airway issues may result in spontaneous remission of the bedwetting. Therefore, if families report snoring or sleep apnoea they should be referred to the appropriate specialist for assessment and treatment.17

Enuresis has also been linked to nocturia in adulthood.18,19

INITIAL ADVICE

Initially advice may be offered whenever a child presents, including in children under five years old.9 Understandable explanations for the cause of the problem should be provided, to reduce the likelihood of punishment and to encourage adherence to treatment.

Underlying constipation should be excluded and treated,20 and behaviours that promote optimal bladder function should be encouraged, as these may lead to resolution for a minority of children.

The child should be encouraged to:

- Drink water-based fluids at approximately two hourly intervals from waking until an hour before bedtime

- Avoid caffeinated and fizzy drinks as these may promote diuresis and bladder overactivity

- Use the toilet about every two hours and just before settling to sleep3

- Avoid protein and salt in the evening, as they increase diuresis.21

Families should be advised that waking their child to toilet at night is unlikely to be helpful in the long term and should be avoided.3

Containment products may be used if desired, but research has found that some children (about 13%) become dry when they stop using disposable products at night.22

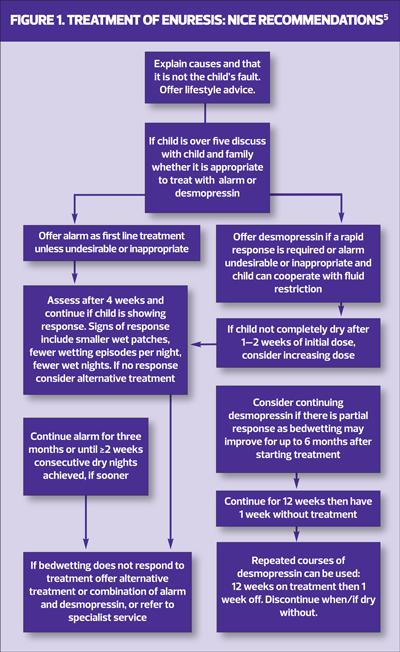

TREATMENT

The two main options for first-line treatment of bedwetting are the enuresis alarm and desmopressin. Information about both options should be provided with the child and family supported to choose the most desirable and appropriate for their situation to try first.

Enuresis alarm

The alarm is likely to be most effective for those who are motivated, have parental support, who use it every night and who are wet two or more nights a week at commencement of treatment.3 It can be successful in those with learning disabilities and should not be excluded because of autism or ADHD. There are no predictors for success with an alarm. However, if there is no progress or poor adherence after four weeks of treatment, it is unlikely to lead to dryness at that point and should be discontinued.23

An alarm may not be suitable in situations where the parents are expressing anger or lack of understanding towards their child.

If an alarm is used, it is important that it is used every night. It does not need to be reset after the first sounding, even if the child is wet again. Parents need to wake their child as soon as they hear the alarm.3 The child should the turn off the alarm and go straight to the toilet to try to void (before any wet linen is changed) and settling back to sleep.

Signs of progress include the child learning to wake to the alarm, the alarm sounding after a longer period of sleep, the child managing to pass some urine in the toilet and dry nights. If none of these are seen within four weeks the alarm should be discontinued.23

If progress is made, the child should continue to use the alarm until they have achieved 28 consecutive dry nights or improvements have not continued after a further two to three months of alarm use. If the alarm does not resolve the problem, it remains an option for a later date, alone or in combination with other treatments, but alternative strategies should be considered.

Desmopressin

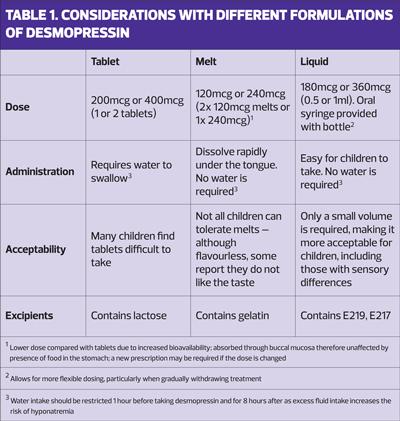

Desmopressin is a synthetic form of the hormone arginine vasopressin. It reduces urine output so that the bladder can accommodate the total volume produced in children with nocturnal polyuria, without the child needing to wake. Desmopressin is available as a 200mcg tablet, an oral solution of 360mcg per 1ml, or as a 120 or 240mcg oral lyophilisate (melt). It is usual practice to start with 200mcg if tablets are used, 180mcg for liquid and 120mcg for the lyophilisate, and to double the dose after a week if the wet nights continue.

Desmopressin is not associated with any safety concerns, and side effects, which include but are not limited to hyponatraemia, nausea, abdominal pain, emotional changes and vomiting, are rare. Contraindications include cardiac insufficiency, treatment with diuretics, a history of hyponatraemia, inappropriate ADH secretion and von Willebrand’s Disease Type IIB.

Desmopressin is given up to an hour before bedtime. Fluid intake must be restricted in the one hour prior to taking it, with no fluids for eight hours afterwards, to prevent hyponatremia, which may occur with excess fluid intake. Desmopressin must not be given if the child cannot comply with the fluid restriction prior to administration for any reason. It should also be omitted if the child is unwell with diarrhoea or vomiting, until they have recovered.24

Response to desmopressin is usually immediate, but it is advisable to use it for at least 1–2 weeks to gauge its effect. If it is not fully effective, the dose can be doubled i.e. 400mcg for the tablets, 360mcg for the liquid and 240mcg for the lyophilisate. If wetting reduces or if the child is dry when taking desmopressin, it may be continued for up to 12 weeks at a time. The child must then have one week without it. If they are dry during the treatment break it does not need to be resumed. If wetting returns, desmopressin may be restarted for further 12-week treatment blocks.24

If there is relapse after a previous response to desmopressin, consider gradually reducing the dose,9 which may be easier with the liquid formulation, or a structured or random withdrawal of treatment.

Children with nocturnal polyuria are likely to respond to desmopressin,25 but its success cannot be accurately predicted. It should therefore not be excluded for any child. As desmopressin comes in different formulations a discussion should be had with the child and parents about which is likely to be most appropriate and acceptable. The cost to the NHS should also be considered.

If the bedwetting does not resolve with the first option chosen, an alternative may be appropriate, option although families may opt to try a different treatment (alarm if they have previously tried desmopressin and vice versa).

Children who do not make progress after treatment with either desmopression or alarm should be referred to a specialist service for further assessment and support.9

Job code: DM 030 Date of preparation: October 2023 This article has been initiated and supported and reviewed solely by ALTURiX https://alturix.com/ Prescribing information for DEMOVO® is available here. Reporting adverse effects: Adverse events should be reported. Reporting forms and information can be founds at https://yellowcard.mhra.gov.uk |

References

1. Ferrara P, Francheschini G, Bianchi di Castelbianco, et al. Epidemiology of enuresis: a large number of children at risk of low regard. Italian Journal of Pediatrics 2020;46(128): doi.org/10/1186/s13052-020-00896-3

2. Austin PF, Bauer SB, Bower W, et al. The standardization of terminology of lower urinary tract function in children and adolescents: update report from the Standardization Committee of the International Children’s Continence Society. Neurourology and Urodynamics 2016;35:471- 481

3. Nevéus T, Fonseca E, Franco I, et al. Management and treatment of nocturnal enuresis – an updated standardization document from the International Children’s Continence Society. Journal of Pediatric Urology 2020;16:10-19

4. Van Herzeele C, Vande Walle J, Dhondt K, Juul KJ. Recent advances in managing and understanding enuresis. F1000Research 2017:6:1881 doi:10.12688/1100research.11303.1

5. Whale K, Cramer H, Joinson C. Left behind and left out: the impact of the school environment on young people with continence problems. Br J Health Psychol 2018;23(2): 253 – 277

6. Wilson GJ. The lived experience of bedwetting in young men living in Western Australia. Australian and New Zealand Continence Journal 2014; 20 (4) 188 – 192

7. Al-Zaben FN, Sehlo MG. Punishment for bedwetting is associated with child depression and reduced quality of life. Child Abuse and Neglect 2015;43:22-29

8. Nevéus T. Pathogenesis of enuresis: Towards a new understanding. Int J Urol 2017;24:174-182

9. NICE CG11. Bedwetting in under 19s; 2010. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg111

10. Butler RJ, Holland P. The three systems: a conceptual way of understanding nocturnal enuresis. Scand J Urol Nephrol 2000;34(4):270-277

11. Van Herzeele C, Dhondt K, Roels SP, et al. Periodic limb movements during sleep are associated with a lower quality of life in children with monosymptomatic enuresis. Eur J Pediatr 2015;174:897-902

12. Van Herzeele C, Dhondt K, Roels SP, et al. Desmopressin (melt) therapy in children with monosymptomatic nocturnal enuresis and nocturnal polyuria results in improved neuropsychological functioning and sleep. Pediatr Nephrol 2016;31:1477–1484

13. Van Herzeele C, Vande Walle J. Incontinence and psychological problems in children: a common central nervous pathway? Pediatr Nephrol 2016; 31, 5, 689 – 692

14. Von Gontard A, Equit M. Comorbidity of ADHD and incontinence in children. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2015;24:127–140

15. McGrath KH, Calwell PHY, Jones MP. The frequency of constipation in children with nocturnal enuresis: a comparison with parental reporting. J Pediatr Child Health 2008;44:19–27

16. Nevéus T. Nocturnal enuresis – theoretic background and practical guidelines. Pediatr Nephrol 2011; 26: 1207 -1214

17. Zaffanello M, Piacentini G, Lippi G, et al. Obstructive sleep-disordered breathing, enuresis and combined disorders in children: chance or related association? Swiss Med Wkly 2017;147(0506):w14400

18. Gong S, Khosla L, Gong F, et al. Transition from childhood nocturnal enuresis to adult nocturia: A systematic review and meta-anlaysis. Res Rep Urol 2021;13:823–832

19. Goessaert AS, Schoenaers B, Opdenakker O, et al. Long-term follow up of children with nocturnal enuresis: increased frequency of nocturia in adulthood. J Urol 2014:191:1866–1871

20. NICE CG99. Constipation in children and young people: diagnosis and management; 2010. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg99

21. Vande Walle J, Rittig S, Bauer S, et al Practical consensus guidelines for the management of enuresis. Eur J Pediatr 2012;171(6):971–983

22. Breinbjerg A, et al. The Effects of Discontinuing Night-time Protection on Incidence of Paediatric Nocturnal Enuresis – a Multicentre Randomised Controlled Trial. Poster 4, presented at Association for Continence Advice Conference 15 – 16 May 2023, Birmingham

23. Larsson J, Borgström M, Karanikas B, Nevéus T. The value of case history and early treatment data as predictors of enuresis alarm response. J Pediatr Urol 2022;19(2):173.e1-173.e7

24. NICE BNF. Desmopressin; 2023. https://bnfc.nice.org.uk/drugs/desmopressin/#medicinal-forms

25. Van Herzeele C, Evans J, Eggert P, et al. Predictive parameters of response to desmopressin in primary nocturnal enuresis. J Pediatr Urol 2015;11(4): 200.e1–200.e8

Related modules

View all Modules