Cardiovascular considerations in patients with type 2 diabetes

INTRODUCTION

The goals of treatment for type 2 diabetes are to prevent or delay complications and maintain quality of life.1 According to some international guidelines, this requires control not only of blood glucose levels, but also cardiovascular risk factor management.1,2

Diabetes is an independent risk factor for atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) and most people with type 2 diabetes will have additional cardiovascular risk factors such as smoking, obesity, hypertension, dyslipidaemia and physical inactivity.1 A multifactorial and simultaneous risk factor management strategy has lead to reductions in both ASCVD events and deaths in patients with diabetes.1 Guidelines from the European Sociey of Cardiology recommend that this multifactorial approach to diabetes management (encompassing blood pressure, lipid profile, platelet inhibition, smoking cessation, physical activity, weight and dietary habits) should be considered in patients with diabetes and cardiovascular disease (CVD).3

Taking this into account, the choice of drug after metformin is becoming increasingly complex: the prescriber needs to consider cardiovascular risk, renal function and other factors such as hypoglycaemia risk, weight, patient comorbidities including frailty, and patient adherence to treatment.1

This module looks at the increased risk of cardiovascular disease (CVD) associated with type 2 diabetes, the role of pharmacotherapy in managing the condition in line with current guidelines, and provides an overview of the Cardiovascular Outcome Trials (CVOTs) for different medicine classes for patient with type 2 diabetes.

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

On completion of this module, you will:

- Be familiar with the association between type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular complications

- Be aware of the evidence from the cardiovascular outcomes trials of agents used in the management of type 2 diabetes

- Understand the latest guidance for the pharmacological management of type 2 diabetes

- Appreciate the importance of a patient-centred approach to management

This module is one of a series of five. Others in the series are:

- Targets for glycaemic control in type 2 diabetes

- Tailoring therapy to the individual patient

- Short-term complications of type 2 diabetes

- Renal considerations in patients with type 2 diabetes

This resource is provided at an intermediate level. Read the article and answer the self-assessment questions, and reflect on what you have learned.

Complete the resource to obtain a certificate to include in your revalidation portfolio. You should record the time spent on this resource in your CPD log.

References

1. Davies MJ, D’Alessio D, Fradkin J. Management of hyperglycemia in T2DM, 2018. A consensus report by the American Diabetes Association (ADA) and the European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD). Diabetes Care 2018;41:2669-2701

2. Buse JB, Wexler DJ, Tsapas A. 2019 Update to: Management of hyperglycemia in type 2 diabetes, 2018. A consensus report by the American Diabetes Association (ADA) and the European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD). Diabetes Care 2020;43(2):487–493

3. Consentino F, Grant PJ, Aboyans V, et al. 2019 ESC Guidelines on diabetes, pre-diabetes and cardiovascular diseases developed in collaboration with the EASD. Eur Heart J 2020;41:255–323

Contents

TYPE 2 DIABETES AND CARDIOVASCULAR COMPLICATIONS

ASCVD is the leading cause of death in people with type 2 diabetes.1 Type 2 diabetes is a substantial independent risk factor for ASCVD, and this risk may be compounded by the presence of additional risk factors including hypertension, dyslipidaemia, obesity, physical inactivity, chronic kidney disease (CKD), and smoking.1

ASCVD risk management is an essential part of diabetes management.1

Every week in the UK, diabetes (both type 1 and type 2) leads to more than 680 strokes, 530 heart attacks and almost 2,000 cases of heart failure.4 Compared with people without diabetes, people with type 2 diabetes are nearly 2.5 times more likely to have a myocardial infarction (MI), more than 2.5 times more likely to develop heart failure, and twice as likely to have a stroke.4

Myocardial infarction (MI)

Diabetes is a major risk factor for the development of coronary artery disease. As well as the higher incidence of MI in patients with diabetes than without, after an MI patients with diabetes have higher rates of morbidity, mortality and further MI than people without diabetes.5

Heart failure (HF)

In the UK, approximately 920,000 people have a diagnosis of heart failure (HF).6 Prevalence of HF, particularly HF with preserved ejection fraction, is higher in patients with type 1 and type 2 diabetes (16-31%) than in the general population (4-6%).5 While some of the difference may be explained by conventional cardiovascular risk factors, diabetes may independently alter cardiac structure and function.5

Stroke

Diabetes (type 1 and type 2) is a strong independent predictor of stroke and cerebrovascular disease.7 Patients with type 2 diabetes have a greatly increased risk of stroke compared with the general population.7 A meta-analysis that included almost 700,000 people’s individual records of diabetes, fasting blood glucose concentration and other risk factors, without initial vascular disease, revealed that patients with diabetes (compared with those without diabetes) were more than twice as likely to have an ischaemic stroke, and more than one-and-a-half times more likely to have a haemorrhagic stroke.8 The risks did not change noticeably after adjustment for lipid, inflammatory or renal markers, and at population level, diabetes was estimated to account for 11% of vascular deaths.8 People with diabetes are also at increased risk of a further stroke, stroke-related dementia, and stroke-related mortality.7

EVIDENCE FROM CARDIOVASCULAR OUTCOME TRIALS

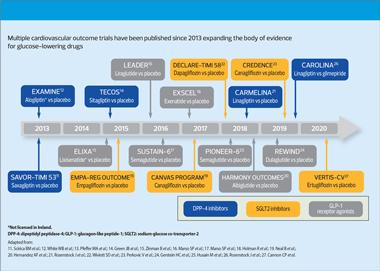

Since 2008 and 2012 respectively, following cardiovascular safety concerns about rosiglitazone, both the US Food and Drugs Administration (FDA) and the European Medicines Agency (EMA) have required cardiovascular outcomes trials (CVOTs) for all new glucose-lowering drugs (Figure 1).9,10

Data from the CVOTs have shown evidence of cardiovascular safety for DPP-4 inhibitors, GLP-1 receptor agonists (GLP-1 RAs) and SGLT2 inhibitors, and for specific agents, of cardiovascular and renal benefits, defined as reductions in major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE), and major adverse renal events (MARE), respectively.

A non-exhaustive list of CVOTs includes:

SGLT2 inhibitors

- EMPA-REG OUTCOME – reported a significant reduction in 3-point MACE (composite of nonfatal MI, nonfatal stroke and cardiovascular death) with empagliflozin vs placebo15

- CANVAS – significant reduction in 3-point MACE with canagliflozin vs placebo19

- DECLARE-TIMI – demonstrated non-inferiority of dapagliflozin to placebo for MACE. Reduction in MACE was not demonstrated, but was demonstrated for the composite of cardiovascular death and hospitalisation for heart failure, drive by the reduction in hospitalisation for heart failure22

- VERTIS-CV – confirmed the cardiovascular safety profile of ertugliflozin and non-inferiority for MACE compared with placebo27

GLP-1 receptor agonists

- LEADER – found significant reductions in 3-point MACE, and also all cause mortality for the GLP-1 RA liraglutide vs placebo16

- EXCEL – found exenatide (once weekly) to be non-inferior to placebo for cardiovascular safety. Exenatide did not reach the threshold for superiority in MACE vs placebo18

- REWIND – showed reduction in 3-point MACE with dulaglutide vs placebo24

- SUSTAIN 6 – demonstrated significant reduction in primary composite of 3-point MACE with semaglutide vs placebo17

- PIONEER 6 – demonstrated cardiovascular safety through non-inferiority of 3-point MACE of oral semaglutide vs placebo25

CVOTs have also confirmed the cardiovascular safety profile of the DPP-4 inhibitors:

- SAVOR-TIMI 53 – saxagliptin vs placebo: found saxagliptin to be non-inferior to placebo for cardiovascular safety. Saxagliptin did not reach the threshold for superiority in 3-point MACE vs placebo11

- EXAMINE – alogliptin vs placebo: found alogliptin to be non-inferior to placebo for 3-point MACE12

- TECOS – sitagliptin vs placebo: showed sitagliptin to placebo to be non-inferior to placebo for 4-point MACE (composite of nonfatal MI, nonfatal stroke, cardiovascular death, hospitalisation for unstable angina)14

- CARMELINA – linagliptin vs placebo: found linagliptin to be non-inferior to placebo for 3-point MACE or composite kidney outcome (time to first occurrence of adjudicated death due to renal failure, end stage renal diseases or sustained decrease of >40% in estimated glomerular filtration rate [eGFR])21

- CAROLINA – linagliptin vs glimepiride: found linagliptin to be non-inferior to glimepiride for 3-point MACE26

GUIDELINE RECOMMENDATIONS

National (NICE, SIGN) and international (European Society for Cardiology-European Association for the Study of Diabetes [ESC-EASD] and American Diabetes Association-EASD [ADA-EASD]) guidelines have been updated to reflect the data from CVOTs, and the presence of cardiovascular disease or indicators of high risk are now primary considerations when choosing treatment after metformin.1-3,28,29

Some international guidelines now recommend either SGLT2 inhibitors or GLP-1 RAs after metformin in people with type 2 diabetes and a history of ASCVD. The ESC-EASD and ADA-EASD guidelines now recommend either an SGLT2 inhibitor or GLP-1 receptor agonist in people with type 2 diabetes at high or very high risk of cardiovascular disease, irrespective of whether they are on metformin.2-4 In patients with cardiovascular and renal comorbidities, who are on metformin, SGLT2 inhibitors and GLP-1 RAs should be considered ‘independently of baseline HbA1c or individualised HbA1c target’.2 Please see reference 2 for current risk definitions and recommendations from the ADA-EASD.

The February 2022 update of the NICE diabetes guideline (NG28) recommends that an SGLT2 inhibitor should be offered in patients with established ASCVD in addition to metformin and should be considered in patients at high risk of developing cardiovascular disease in addition to metformin. The SGLT2 inhibitor should be an agent with proven cardiovascular benefit.29

However, there are currently restrictions on the use of GLP-1 receptor agonists in patients who do not meet current NICE criteria (NICE stipulates a body mass index [BMI] threshold of 35 kg/m2 prior to receiving GLP-1 RA therapy unless insulin therapy would have significant occupational implications or weight loss would benefit other significant obesity-related comorbidities).5 DPP-4 inhibitors are a weight neutral treatment agent and are recommended as a second- or third-line treatment at various stages of type 2 diabetes.1-2

In the management of type 2 diabetes, the choice of drug after metformin is becoming increasingly complex: the prescriber needs to consider cardiovascular risk, renal function and other factors such as hypoglycaemia risk, weight, patient co-morbidities including frailty, and patient adherence to treatment.1

It is worth remembering that DPP-4 inhibitors are recommended for a wide range of patients with type 2 diabetes at various stages of disease, and have been shown to lower blood glucose without increasing the risk of hypoglycaemia or causing weight gain.30

In the self-assessment that follows, hypothetical case scenarios based on fictitious patients are presented. Please refer to the relevant Summary of Product Characteristics before prescribing any of the medications mentioned.

References

1. Davies MJ, D’Alessio D, Fradkin J, et al. Management of hyperglycemia in T2DM, 2018. A consensus report by the American Diabetes Association (ADA) and the European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD). Diabetes Care 2018;41:2669-2701

2. Buse JB, Wexler DJ, Tsapas A, et al. 2019 Update to: Management of hyperglycemia in T2DM, 2018. A consensus report by the American Diabetes Association (ADA) and the European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD). Diabetes Care 2020;43(2):487-493

3. Consentino F, Grant PJ, Aboyan V, et al. 2019 ESC Guidelines on diabetes, pre-diabetes and cardiovascular diseases developed in collaboration with the EASD. Eur Hear J 2020;41:255-323

4. Diabetes UK. Us, diabetes and a lot of facts and stats. https://www.diabetes.org.uk/professionals/position-statements-reports/statistics

5. Leon BN, Maddox TM. Diabetes and cardiovascular disease: epidemiology, biological mechanisms, treatment recommendations and future research. World J Diabetes 2015;6(13):1246-1258

6. NICE NG106. Chronic heart failure in adults: diagnosis and management; 2018. Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng106

7. Fowler MJ. Microvascular and macrovascular complications of diabetes. Clin Diabetes 2008;26(2):77-82

8. Emerging Risk Factors Collaboration. Diabetes mellitus, fasting blood glucose concentration, and risk of vascular disease: a collaborative meta-analysis of 102 prospective studies. Lancet 2010;375(9733):2215-2222

9. FDA. Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: Evaluating the Safety of New Drugs for Improving Glycemic Control Guidance for Industry 2020. https://www.fda.gov/regulatory-information/search-fda-guidance-documents/type-2-diabetes-mellitus-evaluating-safety-new-drugs-improving-glycemic-control-guidance-industry

10. EMA Guideline on clinical investigation of medicinal products in the treatment or prevention of diabetes mellitus. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/scientificguideline/guideline-clinical-investigation-medicinal-products-treatment-prevention-diabetes-mellitus-revision_en.pdf

11. Scirica BM, Bhatt DL, Braunwald E, et al. Saxagliptin and cardiovascular outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. N Engl J Med 2013;369:1317

12. White B, Cannon CP, Heller SR, et al. Alogliptin after acute coronary syndrome in patients with type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med 2013;369:1327-1335

13. Pfeffer MA, Claggett B, Diaz R, et al. Lixienatide in patients with type 2 diabetes and acute coronary syndrome. N Engl J Med 2015;373:2247-2257

14. Green JB, Bethel A, Armstrong PW, et al. Effect of sitagliptin on cardiovascular outcomes in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med 2015;373:232–242

15. Zinman B, Wanner C, Lachin JM, et al. Empagliflozin, cardiovascular outcomes, and mortality in type 2 diabetes. N England J Med 2015;373:2117-28

16. Marso SP, Daniels GH, Brown-Frandsen, et al. Liraglutide and cardiovascular outcomes in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med 2016;375:311-322

17. Marso SP, Bain SC, Consoli A, et al. Semaglutide and cardiovascular outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med 2016;375:1834-44

18. Holman R, Bethel MA, Mentz RJ, et al. Effects of once-weekly exenatide on cardiovascular outcomes in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med 2017;377:1228-39

19. Neal B, Perkovic V, Mahaffey KW, et al. Canagliflozin and cardiovascular and renal events in type 2 diabetes. N England J Med 2017;377:644-57

20. Hernandez AF, Green JB, Janmohamed S, et al. Albiglutide and cardiovascular outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease (Harmony Outcomes):a double-blind, randomised placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 2018;392:1519–1529

21. Rosenstock J, Perkovic V, Johansen OE, et al. Effect of linagliptin vs placebo on major cardiovascular events in adults with type 2 diabetes and high vardiovascular and renal risk. The CARMELINA randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2019;321:69-79

22. Wiviott SD, Raz I, Bonaca MP, et al. Dapagliflozin and cardiovascular outcomes in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med 2019;380:347-57

23. Perkovic V, Jardine MJ, Neal B, et al. Canagliflozin and renal outcomes in type 2 diabetes and nephropathy. N Engl J Med 2019;380:2295-2306

24. Gerstein HC, Colhoun HM, Dagenais GR, et al. Dulaglutide and cardiovascular outcomes in type 2 diabetes (REWIND): a double-blind, randomised placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 2019;394:121-30

25. Husain M, Birkenfeld AL, Donsmark M, et al. Oral semaglutide and cardiovascular outcome in patients with type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med 2019;381:841-51

26. Rosenstock J, Kahn SE, Zinman B, et al. Effect of linagliptin vs glimepiride on major adverse cardiovascular outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes. JAMA 2019;322(12):1155-66

27. Cannon CP, Pratley R, Dagogo-Jack S, et al. Cardiovascular outcomes with ertugliflozin in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med 2020;383:1425-3512.

28. SIGN 154. Pharmacological management of glycaemic control in people with type 2 diabetes; 2017. https://www.sign.ac.uk/media/1090/sign154.pdf

29. NICE 28. Type 2 diabetes in adults: management, 2015 (2022 update). https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng28

30. Trajenta (linagliptin) Summary of Product Characteristics. SmPCs available at EMC: www.medicines.org.uk (GB) and https://www.emcmedicines.com/en-GB/northernireland/ (NI).

Related modules

View all Modules