ESC hypertension guidelines 2024: Guideline in a Nutshell

Practice Nurse 2024;54(5): online only

Practice Nurse 2024;54(5): online only

The latest guideline from the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) sets a new, lower threshold for starting patients on medication to control blood pressure, and opportunistic screening for hypertension from childhood

The recently-published ESC guideline on the management of elevated blood pressure and hypertension stresses the importance of recognising that increasing risk of cardiovascular disease (CVD) related to blood pressure (BP) is on a continuous scale rather than any particular threshold.

New evidence suggests that there are benefits for CVD outcomes of treating patients at high risk of CVD with BP-lowering medications, even if their BP is below the thresholds traditionally used to define hypertension.

The thresholds remain the same, >140 mmHg (diastolic) and >90 mmHg (systolic), but a new BP category has been introduced – ‘Elevated BP’ – defined as 120–139/70-89 mmHg.

Therefore, people with a 10-year risk of cardiovascular disease of 10% or more, or with comorbidities that place them at high risk (such as diabetes), should be started on antihypertensive therapy at e130/80 mmHg, with a treatment goal for most patients of 120-129 mmHg (systolic).

The guideline states the new treatment goal should be pursued as long as it is well tolerated by the patient, but more lenient BP targets can be considered for people with symptomatic orthostatic hypotension, those aged 85 or over, or with moderate-to-severe frailty or limited life expectancy. The guideline also emphasises the importance of using home- or ambulatory BP measurement to confirm that the target systolic BP is achieved.

Where the target of 120-129 mmHg is not pursued, either because treatment is not tolerated, or because the patient has a condition that would rule it out, the aim should be to set a target as low as can be reasonably achieved (the ALARA principle). Personalised and shared decision-making are recommended.

A new recommendation is to deprescribe medication in frail patients, especially if blood pressure declines as frailty worsens.

ASSESSING RISK

The ESC recommends that clinicians should use a risk-based approach to the treatment of raised BP. Individuals with moderate or severe chronic kidney disease (CKD), established CVD, hypertension-mediated organ damage (HMOD), diabetes or familial hypercholesterolaemia (FH) are at increased risk of CVD events.

Irrespective of age, risk in people with elevated BP should be assessed using SCORE2 or SCORE2-OP, or SCORE2-Diabetes for people with diabetes, particularly if they are <60 years of age. Those with a CVD risk of 10% should be considered at increased risk for the purposes of managing their BP. NICE recommends using the QRISK3 tool, except where people are already known to be at high risk, such as those with diabetes, CKD, or FH.2 QRISK3 considers more risk factors than SCORE2, including systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) and regular use of oral corticosteroids.3 SCORE2 only considers five variables – age, gender, smoking status, systolic BP, and non-HDL cholesterol.

Other factors which may increase an individual’s CVD risk include:

- History of complications in pregnancy e.g. gestational diabetes, pre-eclampsia

- High-risk ethnicity (e.g. South Asian)

- Premature onset atherosclerotic CVD

- Socio-economic deprivation

- Autoimmune inflammatory disorders

- HIV, and

- Severe mental illness

Opportunistic screening

Opportunistic screening for elevated BP and hypertension should be considered:

- At least every 3 years for adults aged <40 years

- At least annually for adults aged >40 years

For people who do not currently meet risk threshold for BP-lowering treatment, repeat measurement is recommended within 12 months.

Preventing hypertension and reducing CVD risk

Consider opportunistic screening with office BP measurement to monitor BP during late childhood and adolescence, especially if one or both parents have hypertension, to help predict the development of adult hypertension and reduce CVD risk.

There are also a number of new lifestyle modification recommendations to reduce BP and CVD risk, including:

- Reducing dietary salt to no more than 2-4 g/day (including the sodium contained in processed foods).

- Ensuring dietary potassium intake (from consuming diets high in fruit and vegetables) is >3.5 g/day. However, excessive potassium supplementation should be avoided.

- Restricting sugar consumption, particularly sugary drinks, from a young age

- Although recommended weekly alcohol limits are provided (14 units a week for men, 8 units a week for women) – abstaining for alcohol use altogether is preferred

- Moderate intensity aerobic exercise (>150 minutes/week or /30 minutes/5-7 days) or vigorous exercise (75 minutes/week over 3 days) together with low or moderate intensity resistance exercise two or three times a week

- Aim for a stable and healthy BMI (20-25 kg/m2) and waist circumference (<94 cm in men, and <80 cm in women).

- A healthy, balanced diet e.g. Mediterranean or DASH (Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension) diets, to reduce BP and CVD risk.

- For patients with elevated BP but low/medium CVD risk (<10% over 10 years), BP lowering with lifestyle measures is recommended.

- In adults with elevated BP (130/80 mmHg) and CVD risk greater than 10% over 10 years, try 3 months of lifestyle interventions then initiate pharmacotherapy to lower BP

- For patients with confirmed BP of >140/90 mmHg, initiate BP-lowering treatment promptly, irrespectively of CVD risk.

ESC recommends lifelong BP-lowering treatment (i.e. beyond age 85 years) as long as it is well tolerated. However, because the benefits are uncertain in these patients, it is advisable to monitor tolerance closely. BP-lowering treatment should only be considered if BP is >140/90 mmHg in people who:

- Have pre-treatment, orthostatic hypotension

- Are aged >85 years

- Have clinically significant moderate-to-severe frailty, and/or

- Have limited predicted lifespan (<3 years)

Once BP is controlled and stable on BP-lowering treatment, patients should be followed up at least annually, and other CVD risk factors should be re-assessed.

Communication

The ESC recommends that an informed discussion about CVD risk and treatment, tailored to the needs of the patient, is central to the management of hypertension. Motivational interviewing can also be considered to encourage patients to adhere to treatment to control their BP.

Multidisciplinary approaches are recommended, including appropriate and safe delegation to members of the team other than doctors, to improve BP control in patients with elevated BP and hypertension.

Specific patient groups

Young adults: screen adults diagnosed with hypertension before age 40 years for the main causes of secondary hypertension. In obese young adults, evaluate for obstructive sleep apnoea. Consider screening young adults with hypertension for target organ damage.

Pregnancy: Recommend (in consultation with an obstetrician) low- to moderate-intensity exercise for all pregnant women unless contraindicated, to reduce the risk of gestational hypertension and pre-eclampsia. Starting drug treatment is recommended for pregnant women with a confirmed BP of 140/90 mmHg. In women with chronic/gestational hypertension, the ESC recommends a target of <140/90 mmHg but not below 140/80 mmHg. Systolic BP >160 mmHg, or diastolic BP >110 mmHg indicates an emergency and immediate hospital admission is recommended.

Older and frail patients: Screen older adults for frailty before initiating BP-lowering treatment; consider frail patients’ health priorities and shared decision-making when deciding on BP treatments and targets. If BP drops as frailty progresses, consider deprescribing BP-lowering medications, and other drugs that can lower BP, such as sedatives and prostate-specific alpha-blockers.

Chronic kidney disease: In patients with hypertension and CKD, and eGFR >20ml/min/1.73m2, the ESC recommends SGLT2 inhibitors (which have moderate BP-lowering properties).

Diabetes: For most adults with diabetes and a confirmed BP of 130/80 mmHg, BP-lowering drug treatment is recommended after a maximum of 3 months of lifestyle intervention. The recommended target for systolic BP is 120-129 mmHg, if tolerated.

Routine tests

Routine laboratory and clinical tests should be performed to detect increased CVD risk and relevant comorbidities, such as hyperlipidemia and diabetes.

These include:

- Fasting blood glucose (and HbA1c if raised) to assess CVD and diabetes risk

- Serum lipids (total cholesterol, LDL cholesterol, HDL and non-HDL cholesterol, triglycerides) to assess CVD risk and hyperlipidemia

- Blood sodium and potassium, haemoglobin and/or haematocrit, calcium and TSH to screen for secondary hypertension (primary aldosteronism, Cushing’s disease, polycthaemia, hyperparathyroidism and hyperthyroidism)

- Blood creatinine and eGFR, urinalysis and urinary albumin-to-creatinine ratio to assess CVD risk and target organ damage (renovascular), guide treatment choice and screen for secondary hypertension

- 12-lead ECG to assess for target organ damage (left atrial enlargement, left ventricular hypertrophy) and to assess irregular pulse and other comorbidities (e.g. atrial fibrillation, previous MI).

PHARMACOTHERAPY

The main goal of reducing BP is to prevent adverse cardiovascular disease outcomes, and there is a direct relationship between the intensity of BP lowering and the reduction in CVD events. There is strong evidence for ‘the lower, the better (within reason)’ approach, with exceptions for very elderly or frail patients.

The main drugs use for BP lowering, for which there is good evidence for reduction in CVD events, are:

- Angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEis)

- Angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs)

- Calcium channel blockers (CCBs)

- Diuretics (thiazides, and thiazide-like diuretics), and

- Beta-blockers

The first four are recommended first line. In contrast to the European Society for Hypertension,4 but in common with NICE,2 ESC guidelines do not recommend beta-blockers as first-line therapy. The ESC says this class of drug should only be used when there is a compelling indication for their use (myocardial infarction or heart failure with reduced ejection fraction) or other classes are contraindicated because beta-blockers are less effective at preventing stroke and more frequently discontinued as a result of side effects.

Beta-blockers are also associated with an increased risk of diabetes in some patients, particularly when used with diuretics.

When BP targets are not achieved on optimal doses of the drugs listed above, consider adding spironolactone, a mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist (MRA), but while there is clinical evidence that MRAs prevent CVD events in patients with heart failure, as yet there is no cardiovascular outcome trial evidence for MRAs in other patients with hypertension.

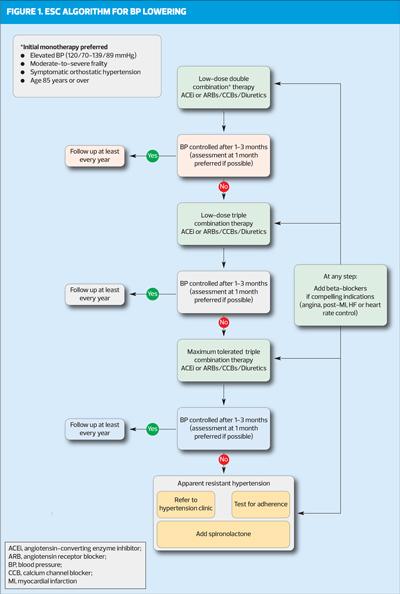

Most patients will require more than one BP-lowering medication to treat hypertension. Combining drugs from different classes can lead to greater BP reduction than increasing the dose of one drug, and using lower doses of more than one drug can result in fewer side effects than using a higher dose of just one agent. Because there are benefits of achieving BP control rapidly, the ESC recommends initiating patients on low-dose combination therapy from the start (Figure 1). Using single-pill combinations is recommended wherever possible, as simplified regimens are known to improve adherence.

The exception to this recommendation is when treating patients with elevated BP (but who fall below the threshold for hypertension), who should be offered monotherapy.

A potential disadvantage of first-line combination therapy is that individuals may respond differently to BP-lowering drug classes, and some patients may benefit from a more personalised approach. Black patients, particularly those from a sub-Saharan African origin, are likely to benefit more from salt restriction and treatment with thiazide or thiazide-like diuretics and CCBs, while renin-angiotension system (RAS) blocker monotherapy may be less effective. Where RAS blockers are used in combination therapy, ARBs may be preferable to ACEis in black patients, in whom angioedema is more common.

Adherence

The ESC task force says that adherence to treatment in hypertension is often poor, with discrepancies between what patients say they do and what healthcare professionals observe. Non-adherence is associated with a higher risk of CVD events, and may explain apparently resistant hypertension. So objective assessment using blood or urine samples is recommended where feasible.

To improve adherence, patients should be encouraged to take their medication at a time that is most convenient to them, rather than at a particular time of day (morning or bedtime). And as stated above, single-pill combinations improve persistence (i.e. treatment continuation) in BP-lowering treatment, and are associated with lower mortality from any cause.

WHEN TO REFER

Referral to a hypertension centre should be considered for patients whose BP remains at >140/90 mmHg despite three or more BP-lowering medications at maximally tolerated doses, including a diuretic. These patients should be investigated by a specialist to exclude secondary and pseudo-resistant hypertension, and optimisation of treatment.

The most common causes of secondary hypertension include:

- Primary aldosteronism

- Renovascular hypertension

- Phaeochromocytoma/paranglioma

- Obstructive sleep apnoea syndrome

- Renal parenchymal disease

- Cushing’s syndrome

- Thyroid disease

- Hyperparathyroidism

- Coarctation of the aorta.

For patients with true treatment-resistant hypertension, pharmacotherapy should be intensified, using spironolactone (or eplerenone if spironolactone is not tolerated) plus a beta-blocker. If BP remains uncontrolled, further intensification may include alpha blockers, centrally acting BP-lowering drugs, and/or potassium sparing diuretics. The ESC also recommends interventional therapy (renal denervation) for selected patients.

A BP of >180/110 mmHg is defined as a potentially life-threatening emergency and requires immediate intervention, usually with IV therapy. Rapid and uncontrolled or excessive BP lowering is not recommended for most hypertensive emergencies as this can lead to further complications.

Symptoms of hypertensive emergency depend on the organs that are affected, but may include headache, visual disturbances, chest pain, shortness of breath, dizziness or other neurological symptoms.

Patients who have experienced a hypertensive emergency remain at high risk and should be screened for secondary hypertension.

In pregnancy, acute onset of severe hypertension (>160/110 mmHg) persisting for more than 15 minutes is considered an emergency and is associated with adverse maternal and perinatal outcomes, independent of pre-eclampsia. Admission for immediate reduction of BP is required.

References

1. 2024 ESC guidelines for the management of elevated blood pressure and hypertension. Eur Heart J; 30 August 2024: https://academic.oup.com/eurheartj/advance-article/doi/10.1093/eurheartj/ehae178/7741010#479375729

2. NICE NG238. Cardiovascular disease: risk assessment and reduction, including lipid modification; 2023. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng238

3. Hippisley-Cox J, et al. Development and validation of a new algorithm for improved cardiovascular risk prediction. Nat Med 2024;30(5):1440-1447

4. European Society of Hypertension. 2023 ESH Guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension. J Hypertension 2024;42(1):194. https://journals.lww.com/jhypertension/fulltext/2024/01000/2023_esh_guidelines_for_the_management_of_arterial.29.aspx

Related guidelines

View all Guidelines