The case for general practice nurse-led group clinics

Louise Brady

Louise Brady

RN, BSc Hons PGDip

Primary Care Nursing Lead NHS England

Dr Marion Lynch

PhD MSc RN RMN

Beverley Bostock

PgDip (Diabetes) MSc (Respiratory Care) MA (Med Ethics and Law) QN

Advanced Nurse Practitioner

Georgina Craig

MA (Hons)

Director, The Experience Led Care Programme

Practice Nurse 2024;54(5):21-25

Based on the available evidence, general practice nurse-led group reviews for diabetes and other long-term conditions should be an integral part of the future delivery of chronic disease management in the UK

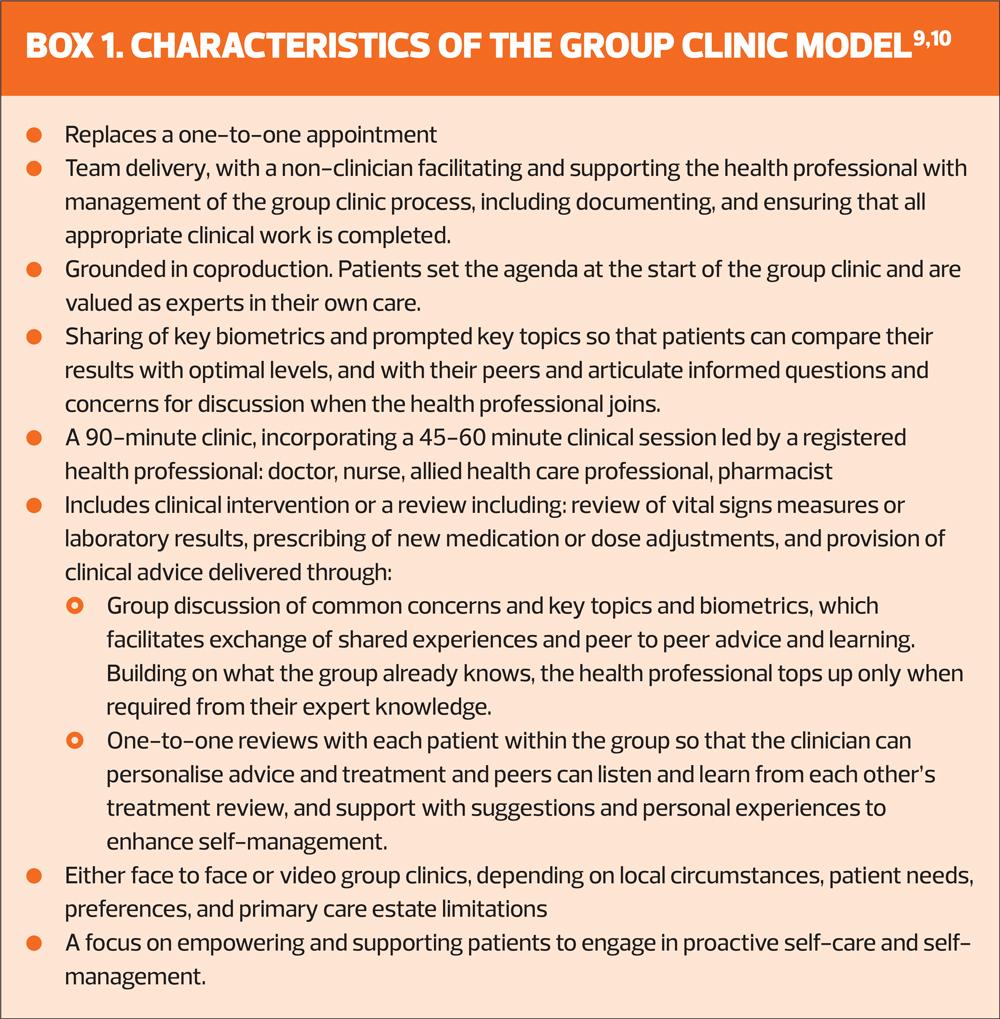

Group clinics deliver care for people who live with long-term conditions in an efficient and person-centred way. In a group clinic, following group discussion focused on what matters to participants, the clinician completes individual clinical reviews with each person in turn. Everyone listens and learns vicariously from others’ reviews.

Diabetes is a long-term condition where improving outcomes relies heavily on patients’ commitment to self-management and lifestyle change. Health care systems are experiencing a steep rise in the prevalence of type 2 diabetes (T2D).

Review appointments can often be repetitive and disheartening for the already stretched general practice nurse (GPN) workforce when, despite their support, patients fail to improve and take control of their condition.

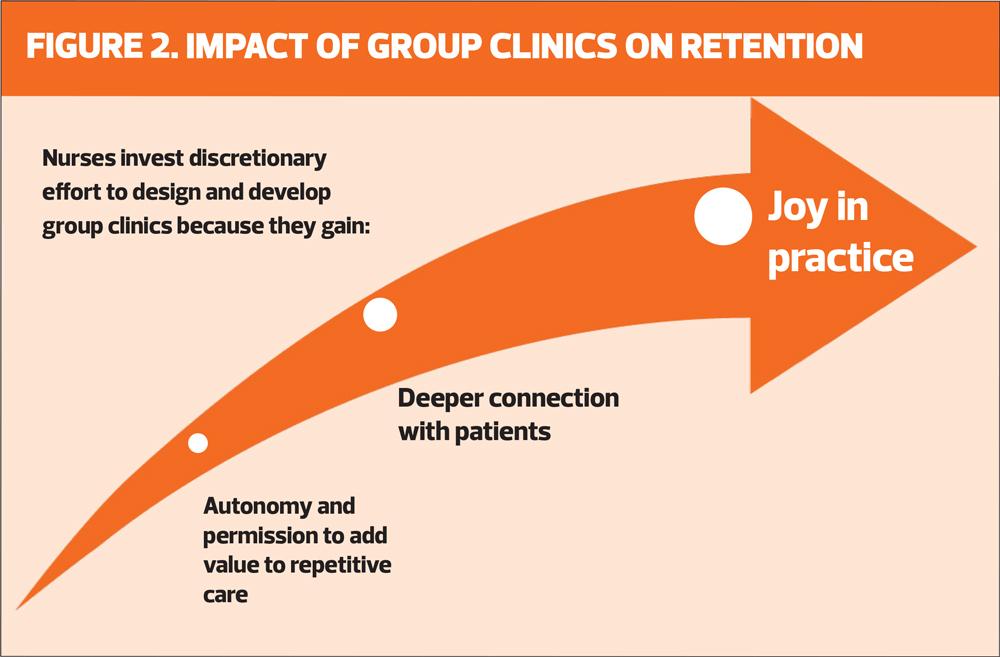

When nurses redesign planned reviews as group clinics, it reignites joy in practice and deepens nurses’ relationships with their patients. Through a renewed sense of autonomy and pride in their work, group clinics may support retention and improve wellbeing among nurses nearing retirement.

CONTEXT

In its 2018 health survey, NHS England found that 43% of people aged over 16 years of age live with at least one long-term condition.1 In addition, 14.2 million live with two or more.2 Long term conditions account for 50% of all appointments in primary care.3 Enabling and supporting people to self-manage and maintain lifestyle change over decades is now critical to health system sustainability.

Providing planned medical care and follow up reviews with patients in a group rather than a one-to-one appointment is nothing new. Inspired by first-hand experiences of group therapy and recognising that many of its benefits would hold true in a medical appointment, Noffsinger developed the concept of group visits, also known in the literature as shared medical appointments.4,5

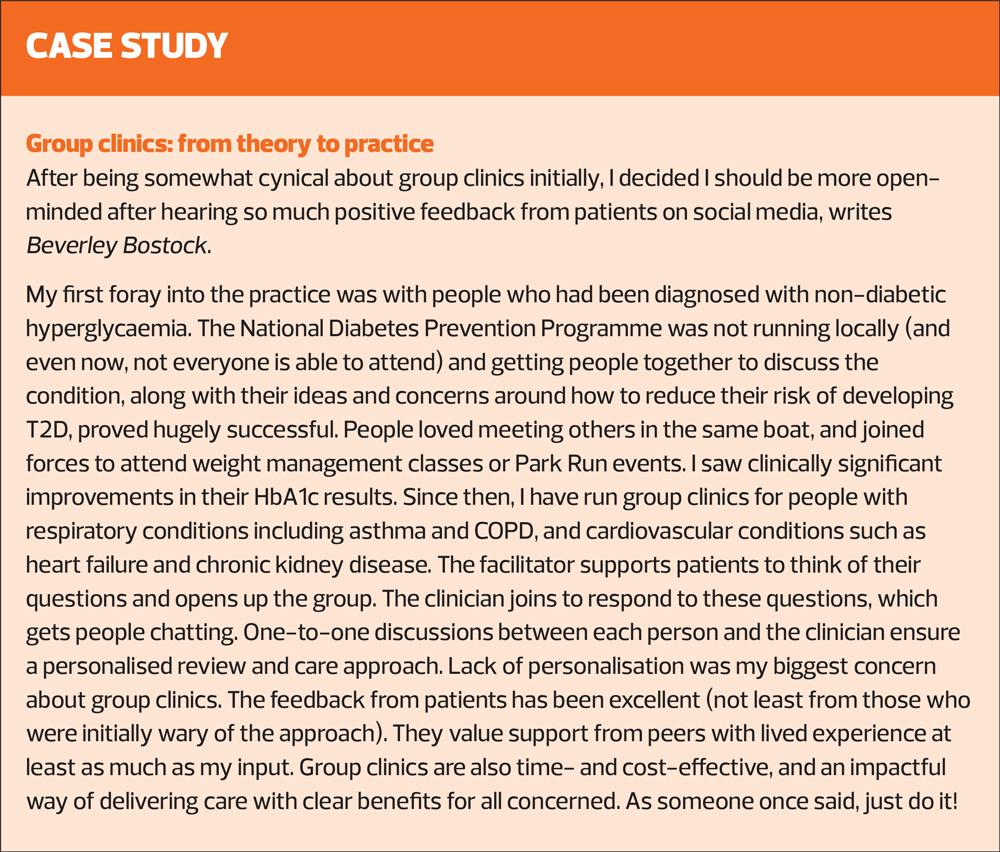

Early primary care pioneers in England emerged in 2009 in Smethwick, Birmingham.6 The team introduced group clinics as part of mainstream planned care for people with diabetes. The 2015 report ‘Making Time in General Practice’,7 included a case study of the application of group clinics in six GP practices in Slough, Berkshire. Consequently, The GP Forward View identified group consultations as one of its ten high impact actions.8 Despite this, no national training nor support was provided to enable primary care teams to make the switch. It has been down to local commissioners to invest.

Since 2018, NHS England’s Nursing Directorate – specifically the Primary Care Nursing team – has been championing the spread of group clinics to develop the leadership potential of general practice nursing.

Its work, undertaken in partnership with The Experience Led Care Programme (www.elcworks.co.uk) was awarded The Health Service Journal (HSJ) Partnership Award for Best Education Programme in 2020 for support provided to train teams to run face to face group clinics, and in 2021 the same partnership won two HSJ Partnership Awards for its video group clinic (VGC) learning programme, developed and delivered to over 500 GP practices across 3 months during 2020 Lockdown.

The Primary Care Nursing team remains at the forefront of work to spread and embed group clinics in England. The team sees group clinics as fundamental to the future of person-centred primary care nursing, and a vehicle to support GPNs to lead improvement in chronic disease management and patient outcomes. Simultaneously, they anticipate that group clinics will help practice nurses take back control and autonomy over their clinical practice so that they deliver more efficient, joyful care that energises them, reconnects them with their core values.

To evaluate this, Keele University, in partnership with NHSE, is leading a review into the impact of group clinics on GPN retention.

GROUP CLINICS AND PERSON-CENTRED CARE

A systematic review of group clinics in primary care to explore the impact on personalisation concluded that, compared with usual care (one-to-one reviews), group clinics lead to measurable improvement in patients’ trust in their clinician.11 Patients who attend group clinics also perceive the quality of their care as higher. Moreover, they report that group clinics are more engaging and empower them as more active participants in their own healthcare, while at the same time improving access and healthcare efficiency.11 More recently, researchers found that patients consider group clinics a positive and a supportive environment to learn about self-care. Carers reported improved communication between carer and patient after group clinics.12

Group clinics are formally recognised in NHS England’s 2023 guidance How to improve care related processes in general practice as a ‘personalised care approach to long term condition management’.13

GROUP CLINICS, CHRONIC DISEASE MANAGEMENT AND PATIENT OUTCOMES

Group clinic appointments for those who live with chronic health issues have been subject to many systematic reviews over the years.11,12,14–17

The best evidence of impact of group clinics is found in research on T2D pathways where most often randomised controlled trials suggest the following positive impacts of group clinics:

- Improved clinical biometrics – in particular HBA1c and blood pressure.12

- Superior preventative care for those from low-income and under-served communities.18

- Improved knowledge of diabetes.19

- More patient-initiated behaviour changes.20

- Reduced A&E visits among vulnerable people with diabetes.21

- Improved quality of life for people living with T2D.22

- % increase in percentage of patients achieving NICE-recommended eight care processes in T2D within 12 months.23

Improving access is critical in the current NHS climate, and this is mirrored in research findings that group clinics absorb service pressures, free up scheduled one-to-one appointments and improve access.24

Gandhi and Craig23 found that a group clinic appointment as the first contact for nurse- or clinical pharmacist-led diabetes reviews in a London general practice with a list of 1,000 people with T2D:

- Freed up clinician time and released a 0.5 FTE advanced nurse practitioner

- Reduced waiting times for annual diabetes reviews from 6 weeks to 2 weeks

- Reduced Did Not Attend (DNA) rates to 5.94%, compared with 11.7% DNA rate for one-to-one reviews.

In England, the most prevalent applications of video group clinics (VGCs) were: diabetes (27%), weight management (17%), cardiovascular (12%) and respiratory conditions (12%), mental health (9%), musculoskeletal conditions (9%), pain management (8%), long COVID (5%) and cancer care (1%).25 VGCs have also been used in postnatal care, and to support healthy eating.26

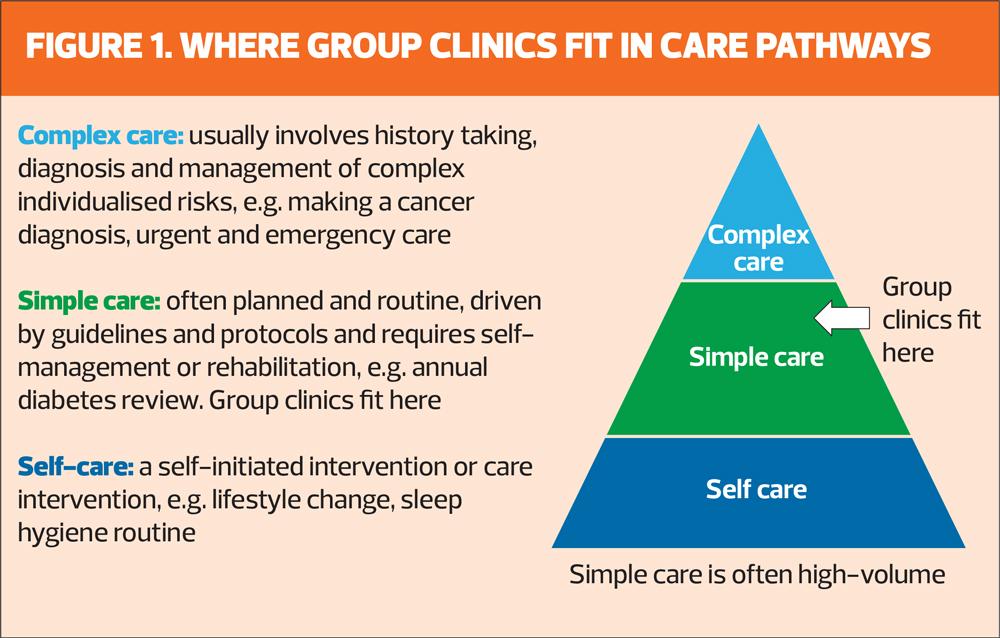

Lynch’s evaluation27 of the Welsh Video Group Clinic Programme examined and stratified the clinician’s activities within the group clinic to identify the kind and complexity of the workload involved. The group clinic models initially selected and developed by outpatient teams in Wales delivered ‘Simple Care’. This is defined as clinical work where a high degree of self-efficacy is needed from patients to improve outcomes.28 It is characterised as planned and routine, driven by guidelines and protocols and thus relatively low risk. In all cases, the Welsh outpatient group clinic models were nurse- or allied health professional-led.

Group clinics and general practice nurse leadership

Group clinics provide general practice nurses with the opportunity to work at the leading edge of clinical practice in relation to management of long-term conditions.

Within The Experience Led Care Programme’s group clinic training team, all the expert clinician mentors are general practice nurses. GPs attending its advanced clinician skills training module learn from these expert nurses how to undertake clinical work in groups.

The power of group clinics as a vehicle for general practice nurse leadership development first emerged in 2018 when evaluation of a Health Education England funded group clinic programme in North-West England found that participating nurses reported that introducing group clinics developed their leadership skills. It also increased their understanding and use of quality improvement techniques.29

AUTONOMY, RETENTION AND JOY IN CLINICAL PRACTICE

Graham et al12 report that clinicians identify several benefits of group clinics, including: more comprehensive patient-led care, the value of peer-to-peer support, reduced repetition, and improved clinic efficiency. Aligned with this, Lynch27 found that staff describe VCGs as restoring joy to repetitive, monotonous, clinical work through deeper connection to their patients.

Lynch27 also reported that having control and autonomy to incorporate VGCs into the design of existing clinical pathways enabled adoption and was highly motivating. It raised investment of discretionary effort and team engagement. Despite the absence of protected time in the Welsh VGC programme, participants invested their personal time to do the extra work entailed in switching to VGCs. A sense of belonging, autonomy and feeling valued and trusted to design their VGCs drove this behaviour.

This personal commitment was echoed by Papoutsi et al26 who reported that enthusiastic staff (clinical and non-clinical) in England invested significant discretionary effort so that VGCs would work and that they found making this change rewarding. The fact all these teams were making change during the COVID-19 pandemic when they faced additional pressures, investment of discretionary effort at this scale is remarkable.

Welsh clinicians described how having the autonomy to improve simple clinical interventions that were not adding value to patient care nor using their clinical skills was a ‘relief’. They shared how VGCs aligned with their professional values. They talked about the privilege of meeting people in their own homes and expressed pride and joy in the difference VGCs had made to patients’ experiences and to the quality of their own working lives. They described how offering VGCs meant that they were able to continue to work rather than shield during the pandemic, and how their experience of working in VGC had changed their minds about leaving their job or retiring.

It is well documented that the ability to exert personal influence over the quality of clinical work is key to successful workforce retention. Lynch’s evaluation is amongst the first to document improved nurse retention as a benefit of group clinic adoption,27 a benefit that other researchers have suggested would emerge.30

SUMMARY

Primary care nurses are already at the forefront of work to spread and embed group clinics in England at National level. The Primary Care Nursing team at NHS England is championing this model. The National Expert Clinician Mentors with the most experience of this model of clinical practice in England work as nurses in general practice.

There is a strong evidence base that supports the adoption of group clinics as a mainstream way of delivering nurse-led chronic disease management in primary care. It is in the gift of general practice nurses to champion this approach at the grass roots.

Doing so will develop their leadership skills on the job, and build their experience of improving quality of chronic disease management.

With strong evidence that group clinics deliver person-centred care, improve patient outcomes, improve access and restore nurses’ autonomy and joy in simple clinical practice, there is mounting evidence that group clinics also support clinician retention and may reduce burnout. Now is the time to embrace this way of practising as part of a positive future vision of modern primary care nursing.

REFERENCES

1. NHS England. Health Survey for England 2018. NHS England, 2019. https://digital.nhs.uk/data-and-information/publications/statistical/health-survey-for-england/2018

2. Stafford M, Steveton A, Thorlby R, et al. Briefing: Understanding the healthcare needs of people with multiple conditions. Health Foundation, 2018. https://www.health.org.uk/publications/understanding-the-health-care-needs-of-people-with-multiple-health-conditions

3. Department of Health. Long Term Conditions Compendium; 2012. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/5a7c638340f0b62aff6c154e/dh_134486.pdf

4. Noffsinger EB. The ABCs of Group Visits. An implementation manual for your practice: Springer; 2013.

5. Noffsinger EB. Group visits - the “secret sauce” of the medical home. Med Home News 2013;5(1): 6-8.

6. Ham C, Smith J, Eastmure E. Commissioning integrated care in a liberated NHS: Nuffield Trust, 2011. https://www.nuffieldtrust.org.uk/sites/default/files/2017-01/1484821582_commissioning-integrated-care-in-a-liberated-nhs-report-web-final.pdf.

7. Clay H, Stern R. Making time in general practice. NHS Alliance; 2015. https://thehealthcreationalliance.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/Making-Time-in-General-Practice-FULL-REPORT-06-10-15.pdf

8. NHS England. General Practice Forward View; 2016. https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/gpfv.pdf

9. NHS England. Video Group Clinic Toolkit; 2020. (Requires an nhs.net email). https://future.nhs.uk/DigitalPC/view?objectID=21327632

10. Craig G, Fallows E. 2021 Video Group Clinics. Implementing video group clinics across primary care and other NHS settings. Requires access to NHS Learning Hub: https://www.e-lfh.org.uk/programmes/video-group-clinics/

11. Wadsworth KH, Archibald TG, Payne, AE, et al. Shared medical appointments and patient centred experience: a mixed methods systematic review. BMC Family Practice. 2019; 20: 97. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12875-019-0972-1

12. Graham F, Tang MY, Jackson K, et al. Barriers and facilitators to implementation of shared medical appointments in primary care for the management of long-term conditions: a systematic review and synthesis of qualitative studies. BMJ Open. 2021;11:e046842. doi:10.1136/ bmjopen-2020-046842

13. NHS England. How to improve care related processes in general practice; 2023. https://www.england.nhs.uk/long-read/how-to-improve-care-related-processes-in-general-practice/

14. Edelman D, McDuffie JR, Oddone E, et al. Shared medical appointments for chronic medical conditions: a systematic review. Washington (DC): Department of Veterans Affairs (US); 2012. https://www.ncbi. nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK99785/

15. Booth A, Cantrell A, Preston L, et al. What is the evidence for the effectiveness, appropriateness and feasibility of group clinics for patients with chronic conditions? A systematic review. Southampton: NIHR Journals Library; 2015. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK333454/

16. Edelman D, Gierisch JM, McDuffie JR, et al. Shared medical appointments for patients with diabetes mellitus: a systematic review. J Gen Intern Med. 2015;30:99-106.

17. Kirsh SR, Aron DC, Johnson KD, et al. A realist review of shared medical appointments: How, for whom, and under what circumstances do they work? BMC Health Serv Res 2017; 17(1): 1-13.

18. Vaughan E, Johnstone CA, Arlinghaus KR, et al. A narrative review of diabetes group visits in low income and underserved settings. Curr Diabetes Rev 2019;15(5):372–381.

19. Riley SB, Marshall ES. Group visits in diabetes care: a systematic review. The Diabetes Educator 2010;36(6):936-944.

20. Dickman K, Pintz C, Gold K, et al. Behavior changes in patients with diabetes and hypertension after experiencing shared medical appointments. J Am Acad Nurse Pract 2011;24(1):43–51.

21. Clancy DE, Cope DW, Magruder KM, et al. Evaluating concordance to American Diabetes Association standards of care for type 2 diabetes through group visits in an uninsured or inadequately insured patient population. Diabetes Care 2003;26(7):2032–2036.

22. Trento M, Gamba S, Gentile L, et al. Rethink organisation to improve education and outcomes (ROMEO): a multicenter randomized trial of lifestyle intervention by group care to manage type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care 2010;33:745–7.

23. Gandhi D, Craig G. An evaluation of the suitability, feasibility and acceptability of diabetes group consultations in Brigstock Medical Practice. J Med Optimisat 2019;5(2):39-44.

24. Birrell F, Brady L, Jones T. Group consultations: benefits and implementation strategies. Practice Nursing. 2018;29(10):484–488.

25. Scott E, Swaithes L, Wynne- Jones G, et al. Use of video group consultations by general practice staff during the COVID-19 pandemic. Primary Health Care 2023;34(1): https://doi.org/10.7748/phc.2023.e1801

26. Papoutsi C, Shaw S, Greenhalgh T. Implementing video group consultations in general practice during COVID-19: a qualitative study. Br J Gen Pract 2022;72(720): e483-e491.

27. Lynch M. Evaluation report. Video group clinics in outpatient settings across Wales 2021-2022. Welsh Government; 2022 (Available from the author).

28. Christensen CM, Bohmer R, Kenagy J. Will disruptive innovations cure health care? Harvard Business Review. 2000; 78(5): 102-112.

29. Health Education England, 2018. Evaluation report. General Practice Nurse led group consultation programme in North West England; 2018 (Available from the author).

30. Thompson-Lastad A, Gardiner P. Group medical visits and clinician wellbeing. Glob Adv Health Med 2020;9:2164956120973979

Related articles

View all Articles