Guidelines in a nutshell: NICE – the final joint guidance on asthma

MANDY GALLOWAY

MANDY GALLOWAY

Editor

Practice Nurse 2024;54(4):12-15

The long-awaited joint UK guideline on asthma consigns SABA-alone treatment to the dustbin of history, recommending a simpler approach to management to ensure all patients with asthma receive appropriate preventive therapy

After a five-year wait, the final joint guidance from NICE, the British Thoracic Society (BTS) and the Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN) was published yesterday, 27 November 2024.

New and updated recommendations cover diagnosis, treatment and monitoring of asthma in children and adults. While the recommendations on treatment align the UK guidance more closely with the recently updated Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA) report – for example, clinicians should no longer offer a short-acting beta2 agonist (SABA) without a concomitant prescription for inhaled corticosteroids (ICS), recommendations on diagnosis and monitoring are likely to prove more controversial, and may be difficult to implement in general practice.

DIAGNOSIS: OBJECTIVE TESTING

If the patient's history is suggestive of asthma, NICE states clinicians should measure the blood eosinophil count or FeNO level in adults with a history suggestive of asthma. Diagnose asthma if the eosinophil count is above the upper end of the laboratory reference range or the FeNO is 50ppb or more.

If neither of these tests confirms a diagnosis, measure bronchodilator reversibility (BDR) with spirometry. Diagnose asthma if reversibility is greater than 12% from baseline, or greater than 10% of predicted normal.

If spirometry is not available or it is delayed, measure peak expiratory flow (PEF) twice daily for 2 weeks. Diagnose asthma if PEF variability (expressed as amplitude percentage mean) is 20% or more.

The NICE Guideline Development Committee (GDC) found that a gradual ‘rule-in approach’ was the most cost-effective diagnostic strategy. Measuring eosinophil counts or FeNO are relative cheap and are highly specific, but both needed to be interpreted carefully: a raised eosinophil count can be caused by factors other than asthma, including other allergies, and FeNO can also be affected by other allergic diseases of the airways, and both measurements are altered in smokers. But, used correctly when there is a history suggesting asthma, they are ‘good rule-in tests’.

Spirometry with reversibility is useful as a test of airway function, and therefore complements a first test that confirms atopic disease, so both components of asthma will have been assessed. Ideally, the method of expressing reversibility after bronchodilator should be based on change in z-scores.

A final test, should the diagnosis still be unclear, would be a bronchial challenge test. The GDC states that this is the most accurate test, overall, but it is more costly than others and is less readily available – it is not available at all in primary care, and infrequently used in secondary care. This is the only additional investigation that is both sensitive and specific for asthma, and while there is likely to be a problem with capacity for challenge testing, the committee hopes that by recommending it, it will encourage services to improve access.

Objective testing in children aged 5-16

Diagnostic testing is harder in children as they may find some tests difficult to perform, and be reluctant to have blood tests.

- Measure FeNO in children with a history suggestive of asthma; diagnose asthma if more than 35ppb

- If FeNO level is not raised, or unavailable, measure BDR. Diagnose asthma if BDR is greater than 12% from baseline or greater than 10% of predicted normal

- If spirometry is not available or it is delayed, measure peak expiratory flow (PEF) twice daily for 2 weeks. Diagnose asthma if PEF variability (expressed as amplitude percentage mean) is 20% or more

- If asthma is not confirmed but still suspected on clinical grounds, either perform skin prick testing for allergy to house dust mite or measure IgE level and eosinophil count.

- Diagnose asthma if there is evidence of sensitisation or a raised IgE level, and the eosinophil count is more than 10.5 x 109 per litre

- Exclude asthma if there is no evidence of allergy to house dust mite or if total serum IgE is not raised.

- If still in doubt, refer to a paediatric respiratory specialist for a second opinion, and possible bronchial challenge test.

The diagnostic strategy for children is based on a rule-in-rule-out approach. FeNO is an acceptable test in children because it avoids the need for a blood test, and because the cut-point of 35ppb is reasonably specific for asthma in the presence of a history suggestive of asthma. However, the GDC noted that FeNO testing equipment is not available in every practice, that some children (a minority) would not be able to perform it, and also that an increasing proportion of children with asthma are non-atopic, and therefore unlikely to have a raised FeNO level. Spirometry with BDR would therefore be an appropriate second test for children who do not have a raised FeNO level, or in whom FeNO could not be measured. Both skin prick testing and measurement of total IgE are sensitive tests, and one or the other should therefore be done next. If negative, asthma is highly unlikely. Although measuring IgE involves a blood test, the sample can be used to obtain an eosinophil count.

GINA2 points out in its recently updated report, that the presence of atopy increases the probability that a patient with respiratory symptoms has allergic asthma, but that this is not specific for asthma, nor is it present in all asthma phenotypes. Skin prick tests with common environmental allergens (not just house dust mite) is simple and rapid to perform, is inexpensive and has a high sensitivity – but a positive skin prick test, or positive specific IgE, does not mean that the allergen is causing symptoms.

GINA also states that FeNO has not been established as useful for ruling in or ruling out a diagnosis of asthma, because while it is higher in some phenotypes of asthma, it is also raised in some non-asthma conditions, including allergic rhinitis and eczema, and is not raised in other asthma types, i.e. neutrophilic asthma, asthma with obesity. FeNO is also lower in smokers and during bronchoconstriction and the early phases of allergic response, and it may be increased or decreased during viral respiratory infections.

Children under 5

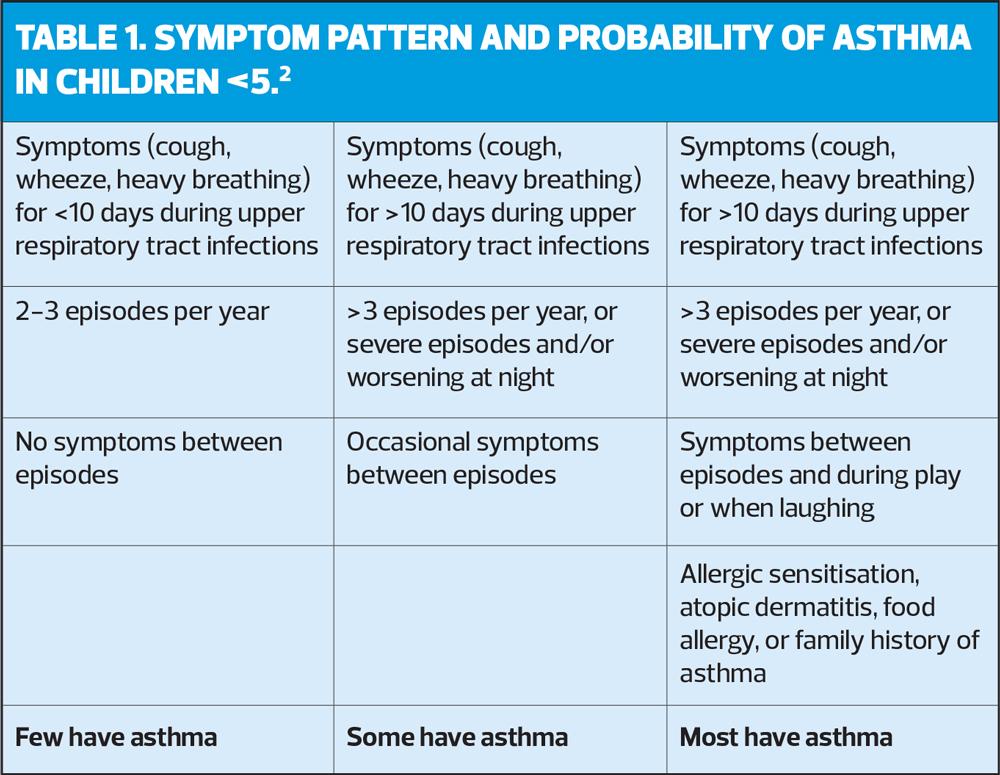

The main issue in children under 5 years is differentiating asthma from symptoms caused by viral infections. There is evidence that asthma is more likely than recurrent viral wheeze when the episodes are frequent or severe, when they occur in the absence of other signs of viral illness, and when the child shows other evidence of atopy.

Although not among the recommendations from NICE, it may be helpful to look at the pattern of symptoms in children aged 5 and younger (Table 1).2

For this age group, NICE recommends treating empirically with low-dose ICS for 8–12 weeks: if this is ineffective, assuming the ICS has been administered correctly, it is appropriate to refer the child for a specialist opinion. If there is improvement it does not mean the child has asthma, as viral wheeze can improve spontaneously, so the ICS should be stopped: if symptoms then reappear within a few weeks, asthma is the more likely diagnosis, and the ICS should be re-started.

Children under 5 should be reviewed on a regular basis, and once they reach the age of 5, objective tests should be attempted. If unsuccessful:

- Try doing the tests again every 6 to 12 months until satisfactory results are obtained

- Refer for specialist assessment if the child's asthma is not responding to treatment.

MONITORING ASTHMA CONTROL

NICE recommends monitoring asthma control at every review. NICE defines asthma control as:

- No daytime symptoms

- No night-time awakening due to asthma

- No asthma attacks

- No need for rescue medication

- No limitations on activity, including exercise

- Normal lung function, and

- Minimal side effects from treatment.

In addition to asking about symptoms, ask about:

- Time off work or school due to asthma

- Amount of reliever inhaler used

- Number of courses of oral corticosteroids

- Active or passive exposure to smoking.

NICE also recommends:

- Using a validated symptom questionnaire (the Asthma Control Questionnaire, the Asthma Control Test, or the Childhood Asthma Control Test) to assess asthma control in adults at annual review.

- Considering FeNO monitoring for people with asthma at their regular review and before and after changing their asthma therapy

- Not using regular peak expiratory flow (PEF) monitoring to asses asthma control unless there are person-specific reasons for doing so.

Recommendations on what to do if asthma control is suboptimal remain unchanged from the 2017 guideline.3

- Confirm adherence to prescribed treatment

- Review inhaler technique

- Review if treatment needs to be changed

- Ask about triggers, including work-related symptoms.

PHARMACOLOGICAL MANAGEMENT

Before starting or adjusting medicines for asthma in adults, young people and children, take into account and try to address the possible reasons for uncontrolled asthma. These may include:

- Alternative diagnoses or comorbidities

- Suboptimal adherence

- Suboptimal inhaler technique

- Smoking (active or passive), including vaping using e-cigarettes

- Occupational exposures

- Psychosocial factors (for example, anxiety and depression, relationships and social networks)

- Seasonal factors

- Environmental factors (for example, air pollution, indoor mould exposure).

The most important message in the 2024 guideline update is:

Do not prescribe shorting acting beta2 agonists (SABA) to people of any age without a concomitant prescription on an inhaled corticosteroid (ICS).

The GDC’s evidence review, which included national reviews of asthma deaths in adults and children, showed that clinical outcomes were poorest in all age groups of people with asthma when using SABA alone – even though this is the cheapest option. NICE therefore states unequivocally that SABA alone should not be used in people with a diagnosis of asthma.

Instead, offer as-needed antiflammatory/reliever (AIR) – a low-dose ICS/formoterol inhaler – to people aged 12 and over with newly diagnosed asthma.

If the person is highly symptomatic, or presents with a severe exacerbation, start with low-dose maintenance and reliever therapy (MART), then consider stepping down to low-dose AIR, used only as needed for symptom relief at a later date when their asthma is controlled.

NICE considered three treatment options for people aged 12 and over with a new diagnosis of asthma:

- SABA as needed with no ICS

- Regular low-dose ICS plus SABA as needed

- A combination inhaler of ICS plus formoterol, a fast onset long-acting beta2 agonist (LABA), used as needed

Compared with both other treatment options, ICS/formoterol as needed showed a reduction in severe exacerbations, and both ICS/formoterol and regular low-dose ICS plus SABA as needed produced consistently better outcomes than SABA alone. A combination inhaler containing ICS/formoterol is more cost-effective than regular ICS plus SABA as needed, and is therefore the preferred option.

Prescribing of SABA alone has been commonplace, although becoming less so because of the publicity around asthma deaths. However, most people aged 12 and over with newly diagnosed asthma are currently treated with a SABA alone, or regular ICS plus SABA as needed. So although combination inhalers are more expensive than SABA alone, the change is expected to generate future savings from a reduction in severe asthma exacerbations.

Sequencing of therapies (people aged 12 and over)

1. Low-dose ICS/formoterol combination (AIR) as needed for symptom control

2. Low-dose MART to people aged 12 and over with asthma that is not controlled with AIR

3. Moderate-dose MART to people aged 12 and over with asthma that is not controlled on low-dose MART

4. Consider adding a leukotriene receptor antagonist (LTRA) if asthma is not controlled on to moderate-dose MART. Give LTRA for a minimum trial period of 3 months (unless there are side effects) then stop if it is ineffective. Follow the MHRA safety advice on the risk of neuropsychiatric reactions in people taking montelukast.

5. Consider adding a long-acting muscarinic receptor antagonist (LAMA) to moderate-dose MART plus LTRA (or to moderate-dose MART alone if an LTRA has proved ineffective) for adults with asthma that is not controlled on current treatment. Give the LAMA for a minimum trial period of 3 months (unless there are side effects) then stop if it is ineffective

6. Refer to a specialist in asthma care when asthma is not controlled despite treatment with moderate dose ICS, LABA, LTRA and a LAMA

The GDC’s main reason for recommending the addition of LTRA ahead of LAMA is that it is simpler to add LTRA than LAMA, and does not require an additional inhaler, which means a lower environmental impact. LTRA is also cheaper than LAMA, but does carry a risk of significant side effects, particularly neuropsychiatric disturbances. If the therapies recommended in 1–5 have been tried, and the person’s asthma continues to be inadequately controlled, various biologic agents are available but these require initiation by a specialist (and are outside the scope of this guideline update).

People with an existing diagnosis of asthma who are stable on current therapy do not have to switch treatment, but consider changing treatment for people who are currently using SABA alone to low-dose ICS/formoterol as needed.

Also consider changing treatment to low-dose MART for people with asthma that is not controlled on:

- Regular low-dose ICS plus SABA as needed

- Regular low-dose ICS/LABA combination inhaler plus SABA as needed

- Regular low-dose ICS/LABA combination inhaler and supplementary LTRA (see warning about side effects, above) and/or LAMA, plus SABA as needed

When changing from low- or moderate-dose ICS (or ICS/LABA combination inhaler) plus supplementary therapy to MART, consider whether to stop or continue the supplementary therapy, based on the degree of benefit when it was initiated.

Initial management and medicines sequencing in children aged 5 to 11

- Offer twice daily paediatric low-dose ICS with SABA as needed.

- Consider paediatric low-dose MART* for children whose asthma remains uncontrolled, provided they have been assessed as able to manage a MART regimen

- Consider increasing to paediatric moderate-dose MART if asthma is not controlled on paediatric low-dose MART

*As of June 2024, no asthma inhalers were licensed for MART use in children under 12, so this use would be off label. Refer to Making decisions using NICE guidelines, https://www.nice.org.uk/about/what-we-do/our-programmes/nice-guidance/nice-guidelines/making-decisions-using-nice-guidelines#prescribing-medicines or SIGN’s Information on prescribing medicines outwith their marketing authorisation https://www.sign.ac.uk/using-our-guidelines/.

For children who are assessed as unable to manage a MART regimen, use twice daily paediatric low-dose ICS plus SABA as needed. Consider adding LTRA if their asthma is uncontrolled on this initial treatment before increasing the dose to twice daily moderate-dose ICS/LABA .

Refer all children whose asthma is uncontrolled on paediatric moderate-dose MART (or ICS/LABA maintenance treatment) to a specialist in asthma care.

Children under 5 years

For children under 5 with newly suspected asthma, consider an 8–12 week trial of twice daily paediatric low-dose inhaled ICS plus SABA if they have symptoms at presentation that indicate the need for maintenance therapy (e.g they have symptoms such as nocturnal cough, exercise-induced wheeze or morning shortness of breath between acute episodes) OR severe (i.e., requiring hospital admission) acute episodes of difficulty breathing and wheeze.

If symptoms do not improve during the trial period, check inhaler technique and adherence, check sources of symptoms in the child’s home, such as mould, cold housing, smokers or pets, and review the diagnosis. If none of these explain the child’s failure to respond to treatment, refer to an asthma specialist.

If symptoms resolve, consider stopping treatment after 8-12 weeks, and review again in 3/12. If symptoms recur by the 3-month review, or the child has an acute episode requiring systemic steroids or hospital treatment, restart regular ICS, and consider a further trial without treatment within 12 months.

If suspected asthma is uncontrolled on a paediatric moderate dose of ICS as maintenance therapy (with SABA as needed), consider adding an LTRA (see warning about side effects, above) for a trial period of 3 months, unless there are side effects, then stopping it if it is ineffective.

If suspected asthma is still uncontrolled, stop the LTRA and refer the child to an asthma specialist for further investigation.

The GDC found that regimes that included ICS showed greater benefits than those without ICS, and that regular ICS alone, or with SABA, was superior to intermittent ICS/SABA. The most important benefits of regular ICS were the reduction in exacerbations and hospital admission.

The committee also recognised the difficulty of making a firm diagnosis of asthma in this age group. Episodes of cough or wheezing are common with recurrent viral infections and can be difficult to tell apart from asthma (See Table 1). Furthermore, there may be concerns about treating such young children with long-term ICS when it may be unnecessary. Therefore, the threshold for referral for specialist care should be low.

DECREASING MAINTENANCE THERAPY

At every annual review of patients with asthma, discuss the potential risks and benefits of decreasing their maintenance therapy when their asthma has been well controlled on their current maintenance therapy.

- Stop or reduce dose of medicines in the reverse order that they were introduced, taking into account clinical effectiveness, side effects and the person's preference.

- Allow at least 8 to 12 weeks before considering a further treatment reduction.

- If considering step-down treatment for people aged 12 and over who are using low-dose maintenance inhaled corticosteroid (ICS) plus a short-acting beta2 agonist (SABA) as needed or low-dose MART, step down to low-dose as-needed AIR therapy (ICS/formoterol combination inhaler).

Agree how the change of regimen will be monitored, and adjust the patient's personalised asthma plan.

PERSONALISED ASTHMA PLANS

As in the previous BTS/SIGN British Asthma Guideline (2019), adults, young people and children aged 5 and over, with a diagnosis of asthma, should be offered a documented personalised action plan (PAAP) and education about asthma. Plans should be reviewed after any hospital admission, acute consultations in primary care or emergency departments, and at annual review, ensuring that the patient understands it

RISK-STRATIFIED CARE

Consider actively identifying people with asthma who are at risk of poor outcomes, and provide care tailored to their needs. Risk factors to review should include:

- Non-adherence to medication

- Over-use of SABA inhalers

- Repeated episode of unscheduled care for asthma

Most studies considered by the GDC showed some reduction in A&E attendance or hospitalisation after risk stratification. Two UK studies in particular showed that when patients were identified by alerts on GP computer systems as needing a course of oral steroids, it reduced the number of hospitalisation and the need for out-of-hours contact or A&E attendance for asthma exacerbations. The committee’s conclusion is that risk stratification is cost-effective.

This recommendation does not go as far as the GINA approach,2 which is to assess risk factors for exacerbation, reduce those that are modifiable, and to minimise oral corticosteroid use. Patients with one or more risk factors should be reviewed more frequently than low risk patients; all patients should be prescribed an ICS-containing treatment, preferably an AIR regimen, to reduce the risk of exacerbations; inhaler technique and adherence should be checked frequently, and corrected if needed.

CONCLUSION

Recent NICE guidelines have seen changes, sometimes dramatic, from the draft for consultation to the final published guidance, but on this occasion, there seems to be much to applaud. The categorical instruction to stop prescribing SABA alone, its embrace of the AIR approach to ensure that ICS is increased in response to increasing symptom levels, and the advice to review all patients to ensure that their treatment includes an ICS-containing treatment, will – it is sincerely hoped – help to reduce asthma attacks, unscheduled care and preventable deaths. Downplaying the role of spirometry in diagnosis will undoubtedly be helpful to practices that no longer offer this service in-house, but to adopt the use of FeNO more widely, both for diagnosis and monitoring, will take significant investment. Without improving access to, and funding for, FeNO, this recommendation will be very hard – if not impossible – to implement.

REFERENCES

1. NICE NG245 . Asthma: diagnosis, monitoring and chronic asthma management. 27 November 2024. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/NG245

2. Global Initiative for Asthma. 2024 GINA main report, Global Strategy for Asthma Management and Prevention; 7 May 2024. https://ginasthma.org/2024-report/

3. NICE NG80. Asthma: diagnosis, monitoring and chronic asthma management; 2017 (Updated 2021). https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng80

Related guidelines

View all Guidelines