Going on the attack to eradicate asthma attacks forever

General practice nurses play an important role in asthma management and, with appropriate training, are in a key position to drive good quality care for people with asthma and to improve currently unacceptable outcomes

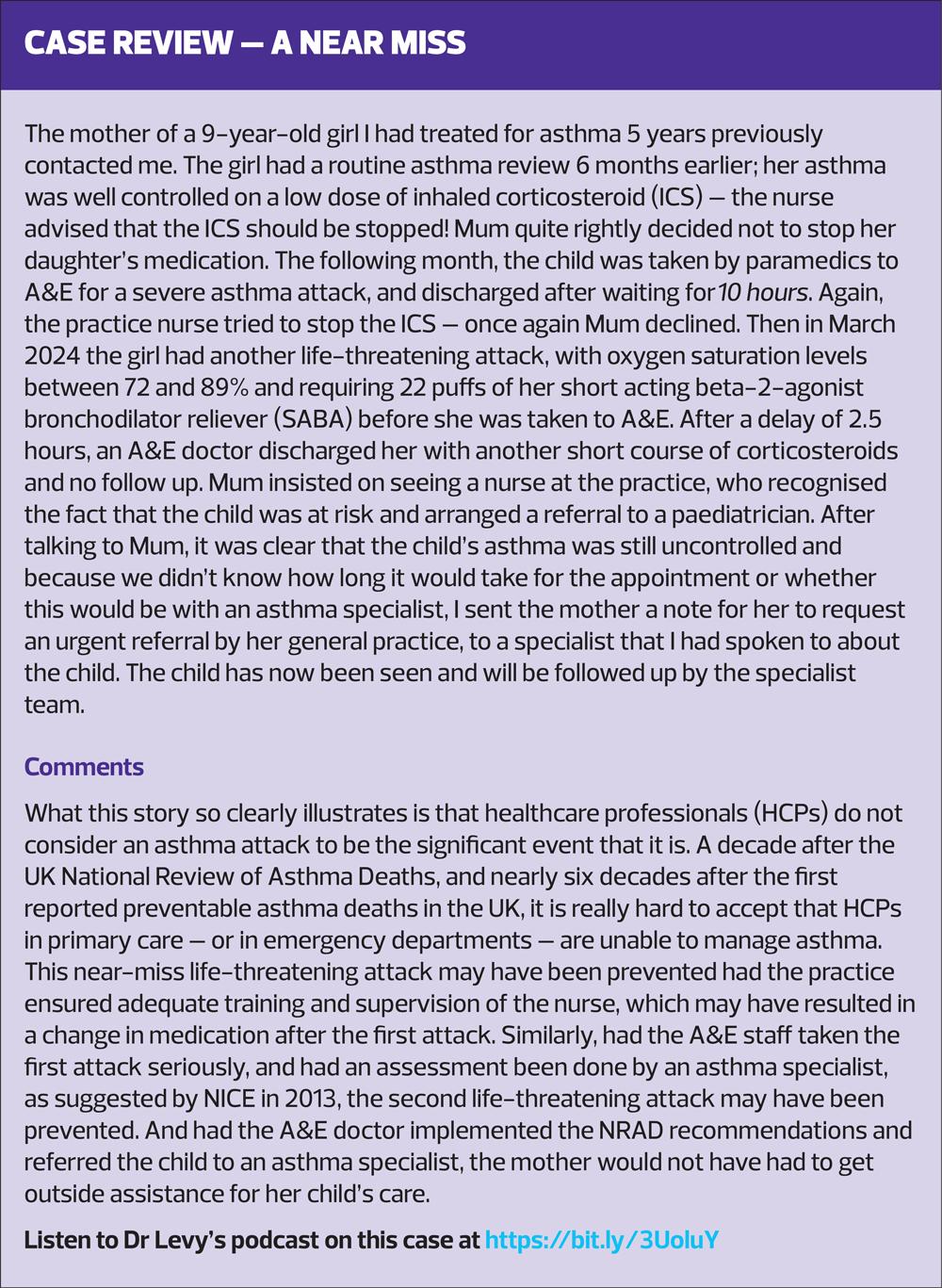

Asthma care in the United Kingdom varies throughout the country and the outcomes generally are not very good. High numbers of patients experience asthma attacks – which are mostly preventable with good chronic (long-term) care, hospital admissions for asthma are not decreasing, and nor are preventable deaths due to this disease. Nurses play an important role in asthma management, both in delivery of acute care in hospital and primary care, and in primary care, nurses are often delegated to do routine as well as post-attack reviews. Sadly, while in the 1990s most nurses providing asthma care had diploma-level training, nowadays – for various reasons – very few have had adequate training and nor do they have access to good quality supervision by doctors or ongoing training.

Given the current state of the NHS, I’m taking the opportunity to suggest that nurses, with appropriate training, take a more active role in ensuring that people with asthma are managed to the highest standards in order to maintain good control of their asthma and prevent asthma attacks. This is really a call for nurses working in primary care (or A&E departments) to drive good quality care for patients with asthma. The theme for World Asthma Day for 2024 is ‘Asthma Education Empowers’ (https://ginasthma.org/world-asthma-day-2024/) and now is the time for this theme to be applied by nurses as well as other healthcare professionals (HCPs). In order to focus on eradicating asthma attacks this article focuses on managing and preventing asthma attacks.

A decade after the UK National Review of Asthma Deaths (NRAD),1 and nearly six decades after the first reported preventable asthma deaths in the UK, it is really hard to believe that HCPs in primary care or in A&E departments continue to manage asthma as an acute disease and not the chronic disease that it is.

In addition to the role of administering drug treatment for the attack, a nurse with asthma knowledge and competence is perfectly placed to also assess progress of the treatment.

In many cases, doctors delegate acute treatment and supervision of asthma attacks, often without asking the nurse’s opinion or drawing on their experience when reviewing the patient after emergency treatment has been delivered. There is an opportunity for a nurse to play an active role in ongoing assessment, raising alerts, and ensuring safety of the patient by critically evaluating their observations made during the attack treatment and ensuring the doctor or senior nurse is aware of these.

Management of an acute asthma attack involves:

1. Treating the attack

2. A post-attack review to ensure the attack is over and also establish why the person had the attack by identifying modifiable risk factors and dealing with these by optimising care – in this way future attacks can be prevented. In addition, I suggest:

3. A process which will help primary care practices ensure people with asthma are appropriately managed and this involves a formal system for ongoing reflection on quality control – a so called 7-step plan.

ACUTE ASTHMA CARE

Some health care professionals prefer to use the term ‘asthma exacerbation’ when someone’s asthma flares up. I prefer the term ‘asthma attack’ because it conveys a sense of urgency and risk for both patients and HCPs.

Is the person having an asthma attack?

When someone known to have asthma consults with respiratory symptoms, two important initial questions are: is the person having an asthma attack? And is it safe to send the person home? Then once the attack has been treated the next question is – why did the attack happen and how can the next one be prevented?

An asthma attack may develop very suddenly and sometimes this does happen; in fact a person may consult for the first time with an asthma attack before the diagnosis has been made. However, in most cases attacks develop slowly over weeks or days. A difficulty for clinicians is that the symptoms may and do fluctuate, so the person may appear well when consulting. Ask when they first started getting these respiratory symptoms, whether they have been using their reliever medication and did it help? How long did the relief last?

Increased use of relievers is an indication that this may be an attack. Benefit or relief of symptoms after using a reliever is another clue this is an attack. If the benefit is not lasting more than four hours, it is potentially a signal of a life-threatening attack, because the bronchodilator effect of SABA inhalers should last for four hours.

Ask whether the person has been checking their peak expiratory flow (PEF) and if so, what is their best reading and how much the readings have been fluctuating. A 10% change in adults and 13% change in children from morning to evening or day to day,2 indicates reversible airflow obstruction and probable asthma; if the readings are below 60% of their best readings that would indicate the attack is severe; and if below 30% of best, it is life-threatening, requiring urgent hospital transfer.

Has the person been measuring their oxymetry? Levels below 94% are serious and below 91%, life-threatening. In a person with dark skin, the level may be falsely reassuring – oxygen levels may actually be 4% lower than the oximeter reading.

In these cases it's important to also use respiratory rate as another indicator of severity if raised. If the respiratory rate is high for the person’s age that’s an important clue that the attack is severe. Can you hear wheezing on auscultation? If yes, then the person has at least 30% obstruction of the airways,3,4 and if you can’t hear any air movement or breath sounds, the attack may be very serious and an ambulance may be needed.

Pulse rate and blood pressure should also be measured – low blood pressure is a sign the attack may be severe. Having said all this – remember that someone having an asthma attack may have none of the features described here, so the history and your clinical judgement are important.5

Assessing what happens during an attack

Objective measurements before during and after treatment include: pulse, respiratory rate and blood pressure, as well as assessing breathing difficulty (use of accessory muscles), tiredness or exhaustion, pulse oximetry, peak expiratory flow (PEF) or spirometry, should be measured and considered in deciding to either send someone home or admit them for inpatient hospital care.2

Ideally, nurses working in front line medical facilities in primary care, A&E departments or secondary care should be trained in both acute and chronic asthma care. Knowledge of acute asthma and in particular the signs that an attack may be life-threatening is essential. However, someone who may be at risk of developing into a severe attack may have no symptoms or signs at the time of assessment.5 So for example, a child who has been ill with breathing difficulty, may have been treated by a parent with emergency high dose SABA and may then appear fit and well and running around the surgery the next day.

In an asthma attack three things happen: the airway passages (or bronchi and bronchioli) get very irritable so they go into spasm and become narrower; the walls of the air passages swell due to influx of inflammatory cells such as eosinophyls; and the airways fill with mucus and phlegm. Then with high doses of SABA either via a nebuliser or a spacer, some of the spasm improves and the person is able to cough up some of the phlegm and they may feel better – which may just be for hours or even some days. And a parent, patient or nurse or doctor may be lulled into a false sense of security thinking that the attack has resolved. However, the beneficial effect of the acute treatment with a SABA may be short lived and the person may deteriorate soon afterwards. For example, in the NRAD, 10% of those who died had been discharged from hospital treatment for attacks within 28 days. Also the author is aware of at least four potentially preventable asthma deaths where the individuals died within 25 hours, 36 hours, 5 days, and 12 days, after being sent home following acute treatment for an attack.6-9

The main problem in these cases was that the HCPs failed to take the attacks seriously by thoroughly assessing their severity, and ensuring appropriate ongoing supervision, in hospital if needed. Treatment of an asthma attack is not just simply to provide acute bronchodilator therapy and send the person home with a three- or five-day course of oral corticosteroids (OCS) – it also involves a detailed assessment to enable a clinical decision to be made on what action is needed there and then, and subsequently.

If someone is sent home after treatment of an attack, safety netting advice (i.e. when and how to call for help) and a post-attack review are essential. A self-management plan should be updated or issued, and prescription written for a peak flow meter to record twice daily readings that will help both the patient and any HCP involved in their care to subsequently decide when it is safe to stop taking oral corticosteroids.

POST-ATTACK REVIEW

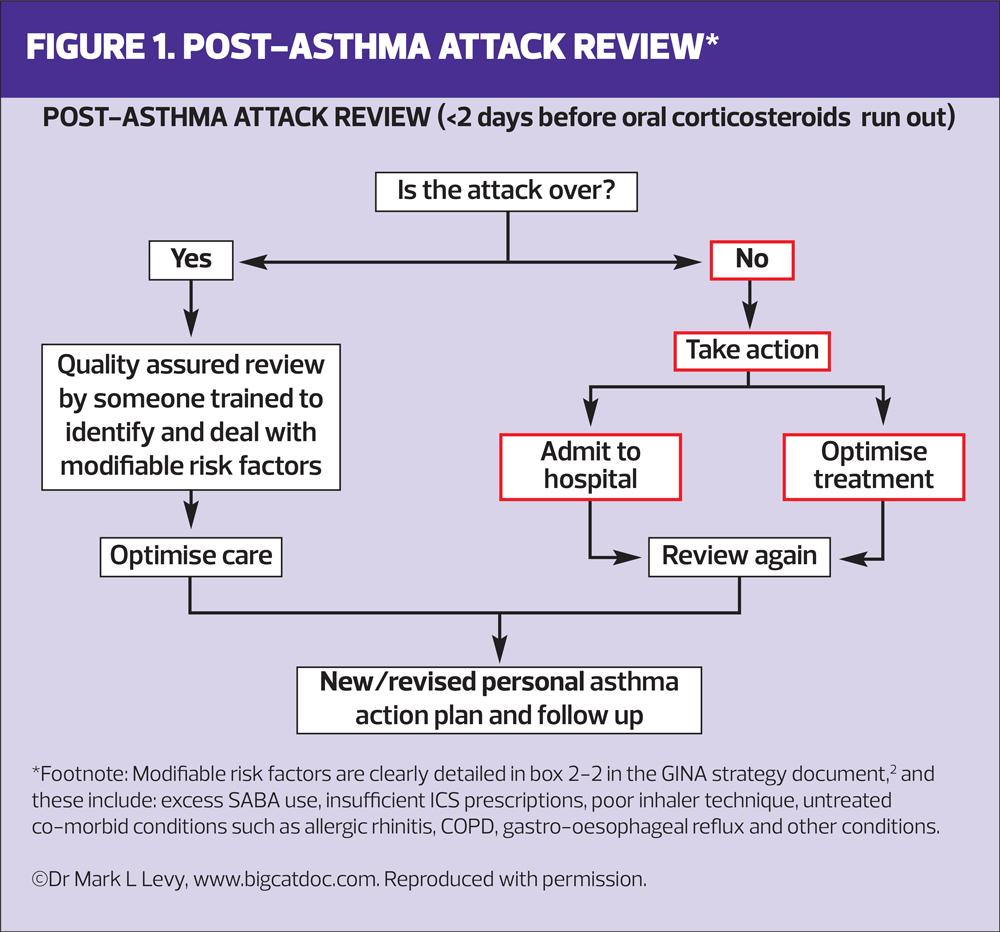

The reason why guidelines recommend a post-attack review is first to establish whether the attack is over or if more treatment or hospital admission is needed; and secondly, so that modifiable risk factors can be identified and dealt with to prevent future attacks (see Figure 1). Ideally the post attack review will be done within a few days of treatment of the attack, and certainly before the OCS runs out. Also, ideally the person should be recording twice daily PEF readings, and some people have their own oximeters and may be recording these values.

Is the attack over? Has it resolved?

The assessment for whether the attack is over or not is similar to the assessment described above to determine whether someone has an attack and how bad it is. If the person still needs to use SABA, is waking at night due to respiratory symptoms, has rapid respiratory or pulse rate, has fluctuating or reducing PEF readings, or has low oxygen saturation the attack has not yet resolved. Either more oral corticosteroids, increased dose of ICS, anti-inflammatory reliever therapy (AIR),10 or referral to hospital may be appropriate. In either event, that person should be assessed by a trained asthma clinician.

Why did the attack happen: identify modifiable risk factors

GPs are incentivised to perform a routine annual asthma review in their patients. However, asthma fluctuates from day to day and an assessment on a good day when the person’s asthma is well controlled is unhelpful. A detailed asthma assessment after each and every asthma attack is far more informative;2,11 record these as ‘annual reviews’. In this way the review would serve both to ensure remuneration for the practice and also possibly save the patient from another attack, hospital admission or even from dying from asthma.

Patient safety is ensured by focussing on the underlying chronic asthma disease and dealing with modifiable risk factors that could have caused the attack (see Figure 1).

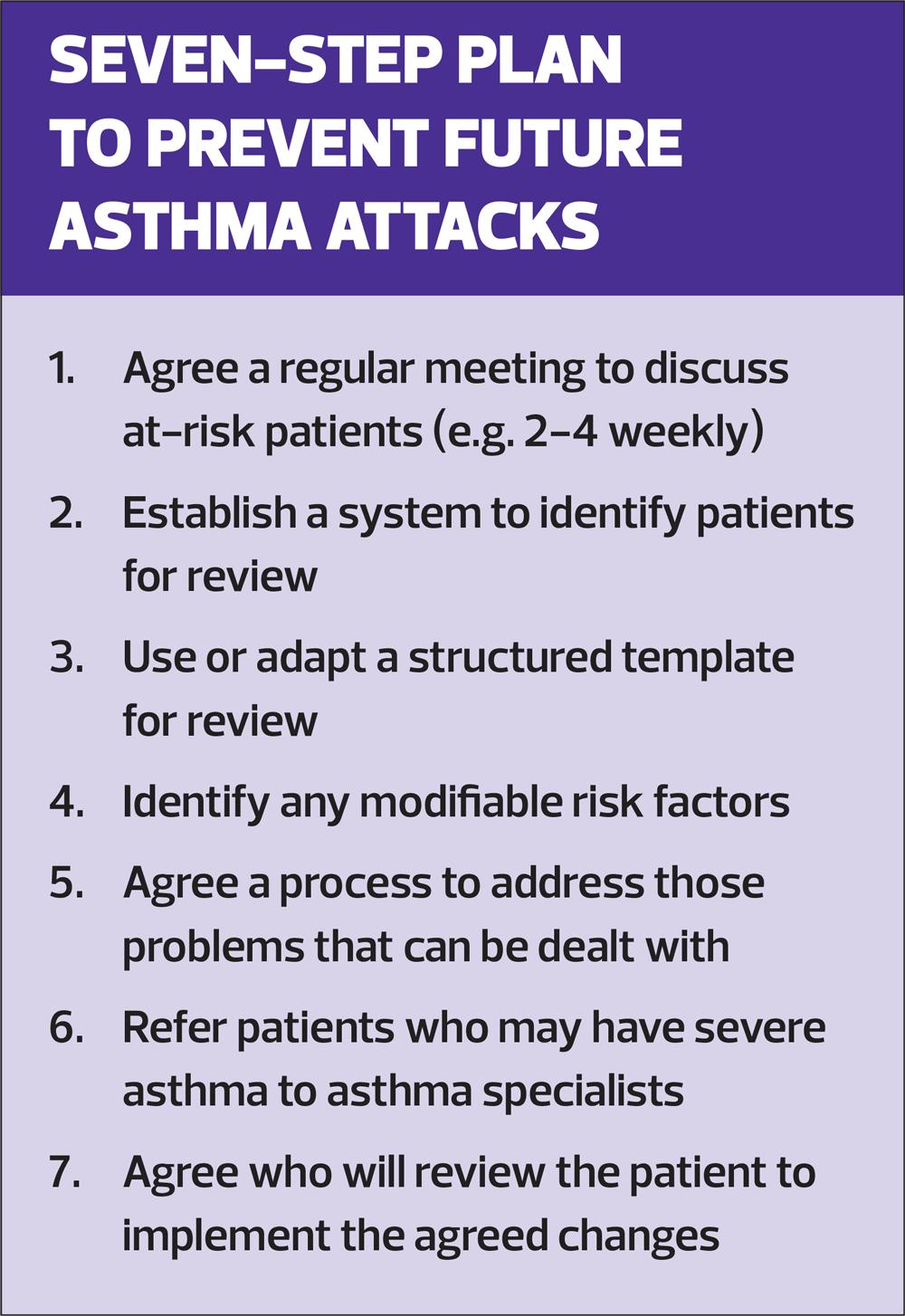

A system for ongoing quality control – a 7-step plan

Asthma has not been very high on the UK national agenda for health care and despite poor outcomes,12 being the commonest chronic childhood disease and one of the commonest adult diseases many local providers have not prioritised asthma. Therefore it’s time for primary care practices themselves with the help of a nurse with asthma training to drive this forward. The 7-step plan is quite simple and practical way to address this (Box 1).13

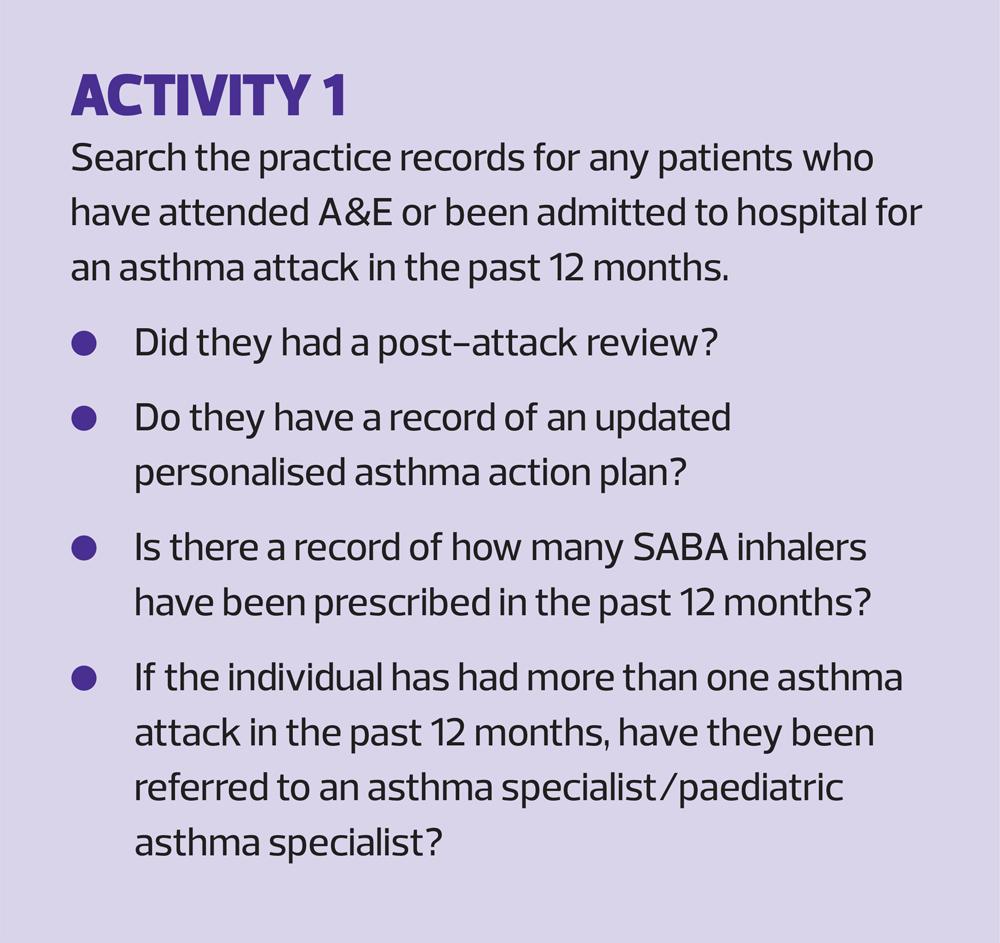

Once the practice agrees to meet at least once a month and to accurately code every asthma attack in patient’s records. The computer code ‘Acute asthma attack’ should be used for anyone who:

- Is treated with high dose SABA either via a spacer or nebuliser;

- Is prescribed or uses a short course of oral corticosteroids;

- Attends A&E; or

- Is admitted to hospital for an asthma attack.

Then each of these patients should be allocated to a clinician in the practice to extract information from the records using a form available online,13 based on an audit that resulted in a 16% reduction in admissions by children with asthma the following year.14

These cases should be discussed at the regular practice meeting attended by all members of staff who deal with patients. Decisions on what action is needed for those particular patients should be agreed, and any system changes that need to be implemented in the practice should be identified and agreed. Interventions may include ensuring adequate ICS prescriptions are collected by patients, reducing individuals’ reliance on SABAs, changing inhaler device where appropriate for individuals, and removing SABA prescriptions from repeat prescribing as a practice policy – anyone requesting a SABA should be seen urgently or an instruction given to reception staff to expedite an emergency appointment for those with asthma presenting with poor control.

This system could begin by focusing on children and young people and then extending to all ages – depending on how many patients in the practice are suffering from acute asthma attacks: ideally there should be none because all but very few asthma attacks are preventable. Positive outcomes will be improved individual patient care, safety and satisfaction, reduction in asthma attacks, reduction in hospital admissions and reduction in practice workload.

In summary, it is really time for nurses to take a lead in improving asthma care in primary care in the UK. This article has focused on dealing with the major problem to start with – too many people are suffering from poor asthma control and dangerous, distressing attacks. By ensuring attacks are dealt with in accordance with latest guidance to ensure they resolve completely, followed by detailed timely post-attack reviews rather than performing routine annual reviews which may be done on a day when the person’s asthma is well controlled, nurses have an opportunity to end a lot of patient suffering. Then by initiating and implementing a systematic practice approach to deal with all asthma attacks as significant events everyone could benefit – patients as well as practice staff.

REFERENCES

1. Why asthma still kills: the National Review of Asthma Deaths (NRAD) Confidential Enquiry report Royal College of Physicians. London; 2014. https://www.rcplondon.ac.uk/projects/outputs/why-asthma-still-kills

2. Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA). The Global Strategy for Asthma Management and Prevention; 2024. https://www.ginasthma.org.

3. Noviski N, Cohen L, Springer C, et al. Bronchial provocation determined by breath sounds compared with lung function. Arch Dis Child 1991;66(8):952-5.

4. McFadden ER Jr, Kiser R, DeGroot WJ. Acute bronchial asthma. Relations between clinical and physiologic manifestations. N Engl J Med 1973;288(5):221-5.

5. Scottish Intercollegiate Guideline Network (SIGN), the British Thoracic society (BTS). British guideline on the management of asthma; 2019 https://www.sign.ac.uk/media/1048/sign158.pdf.

6. Radcliffe S. Regulation 28 Statement in the matter of Sophie Holman (Deceased) 2019 https://www.judiciary.uk/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/Sophie-Holman-2019-0035_Redacted.pdf

7. Carney T. Regulation 28 statement in the matter of Tamara Mills (Deceased). 2015 https://www.judiciary.gov.uk/wp-content/uploads/2016/01/Mills-2015-0416.pdf

8. Radcliffe S. Regulation 28 Statement in the matter of Michael Uriely (deceased) 2017 https://www.judiciary.gov.uk/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/Uriely-2017-0069_Redacted.pdf

9. Persaud N, Senior Coroner East London. Regulation 28: Report to Prevent Future Deaths 2020. https://www.judiciary.uk/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/Kalila-Griffiths-2020-0299_Redacted.pdf.

10. Levy ML, Beasley R, Bostock B, et al. A simple and effective evidence-based approach to asthma management: ICS-formoterol reliever therapy. BJGP. 2024;74(739):86-9. https://bjgp.org/content/74/739/86

11. Levy ML, Bacharier LB, Bateman E, et al. Key recommendations for primary care from the 2022 Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA) update. NPJ Primary Care Respiratory Medicine. 2023;33(1):7.

12. Levy ML, Fleming L, Bush A. Asthma deaths in children in the UK the last straw! BrJ Gen Pract 2024:bjgp24X738201. https://bjgp.org/content/early/2024/04/29/bjgp24X738201

13. Levy M. An asthma attack is a red flag: A 7-step plan 2024 https://bigcatdoc.com/2024/01/10/2024-identify-that-an-asthma-attack-is-a-red-flag/.

14. Levy ML, Ward A, Nelson S. Management of children and young people (CYP) with asthma: a clinical audit report. NPJ Primary Care Respiratory Medicine 2018 2018/05/21; 28(1). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41533-018-0087-5.

Related articles

View all Articles