Identifying and managing patients with bronchiectasis

Samantha Prigmore

Samantha Prigmore

RGN BSc, MSc

Independent Consultant

Respiratory Nurse

Practice Nurse 2024;54(1):21-26

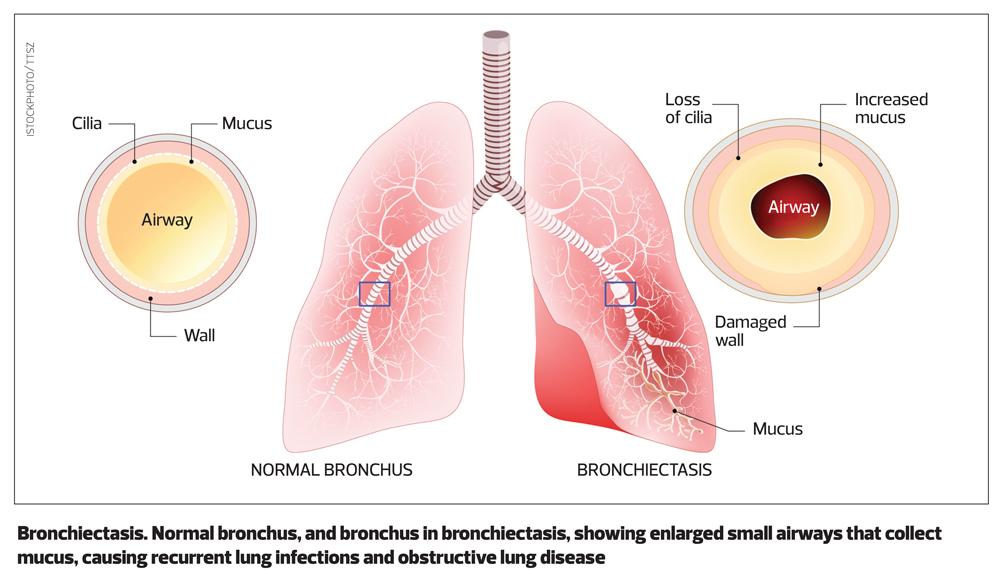

Bronchiectasis is a chronic condition in which irreversible damage to, and dilation of the bronchi, leads to symptoms of persistent or recurrent bronchial sepsis.1 Diagnosis can be challenging, but the condition can be successfully managed in primary care

Bronchiectasis is defined by the presence of permanent and abnormal dilatation of the bronchi,2 with the name being derived from two Greek words: bronckos, airways and ectasis, widening.

The dilatation of the bronchi is irreversible, and results in the elastic and muscular tissue being destroyed by acute or chronic inflammation and infection. This impairs of the natural drainage of bronchial secretions, which can become chronically infected resulting in mild to moderate airway obstruction. Unless appropriately managed, the combination of infection and chronic inflammation, results in progressive lung damage.

PREVALENCE

Bronchiectasis is a relatively common respiratory condition affecting people of all ages. A GP practice of 10,000 patients will have around 50 adult patients with bronchiectasis, with 1% of people over 70 years of age living with the condition. It is more common in females than males, 5.6/1000 females versus 4.9/1000 males.3

CAUSES

There are several known causes of bronchiectasis where the individual is more prone to respiratory infection, or the condition affects the ability to clear secretions from the chest.4 These include:

- Post respiratory related infection e.g., pneumonia, whooping cough, measles, or mycobacterial infections.

- Presence of a muco-ciliary disorders e.g., primary ciliary dyskinesia, Kartagener’s syndrome, (which comprises of three conditions; situs inversus, chronic sinusitis and bronchiectasis), Youngs syndrome (which is characterised by male infertility, bronchiectasis, and sinusitis)

- Obstruction of the airway lumen e.g., a foreign body, lung cancer or tuberculosis

- Cystic fibrosis, which whilst normally diagnosed in the first few weeks of life, can be missed and diagnosed later in life.

- Existing respiratory conditions e.g., chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis (ABPA).

- Immune disorders e.g., hypogamma-globulinemia, HIV infection and cancers.

- A history of aspiration, including gastro-oesophageal reflux disease

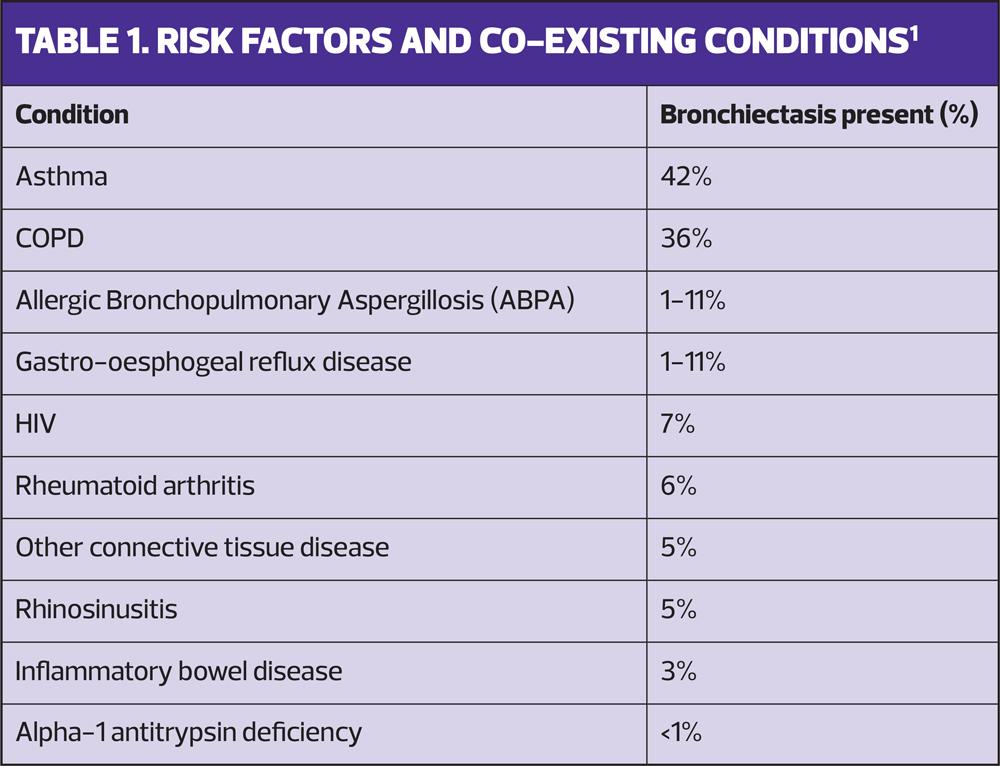

Despite the known causes of bronchiectasis, the underlying cause is idiopathic in 44% of cases.5 In addition to the known causes, there are several risk factors and health conditions which are associated with bronchiectasis (Table 1).

PRESENTATION

The overwhelming presenting symptom in patients with bronchiectasis is a chronic productive cough, which is present in 98% of people. Unfortunately, patients may have had a chronic productive cough for many years before bronchiectasis is diagnosed. Experiencing chronic respiratory symptoms from childhood is not uncommon. Other common presenting symptoms include fatigue (74%), chronic rhinosinusitis (70%) and dyspnoea (62%).2

DIAGNOSIS

Bronchiectasis should be suspected in patients with a recurrent or persistent cough that has lasted for more than 8 weeks and features the production of purulent or mucopurulent sputum,1 with a lower index of suspicion for bronchiectasis if there are co-existing factors (Table 1).6

In addition, when undertaking annual reviews of patients with COPD and asthma, consider the possibility of underlying bronchiectasis. Patients with COPD who have experienced of two or more exacerbations a year and a previous positive sputum sample for Pseudomonas aeruginosa while stable, and patients with difficult to treat asthma, should be investigated for bronchiectasis.

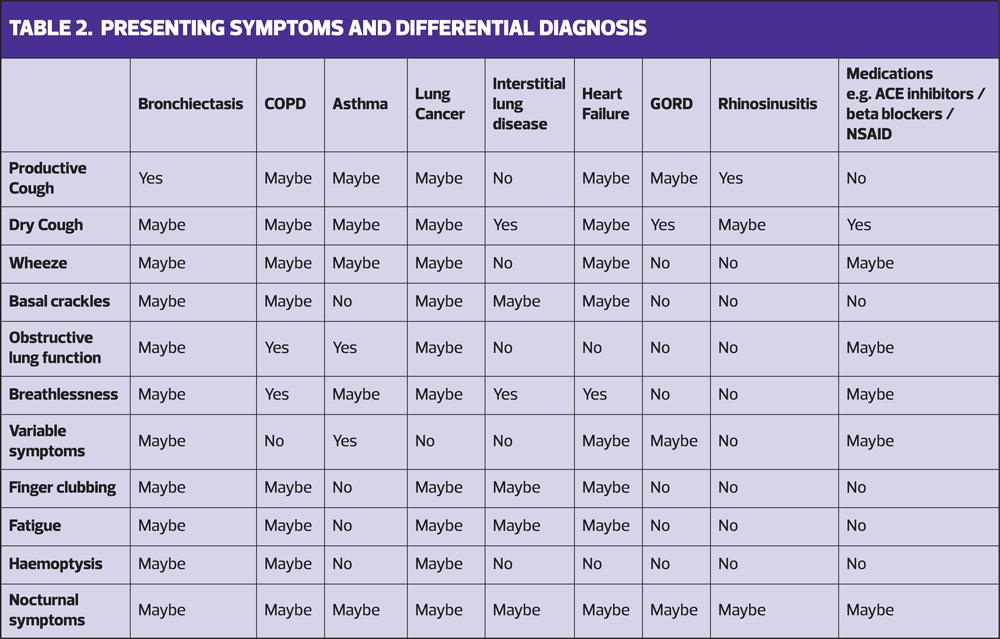

Diagnosis can be challenging because the presenting symptoms are similar to those of other conditions and comorbidities such as COPD and asthma. Table 2 highlights the differential diagnosis and the likely symptoms which may be present. It worth remembering that patients may have more than one condition which may be driving their symptoms, and it is important to identify and treat the underlying causes.

Making the diagnosis

A detailed clinical history and examination can help to determine the likelihood of bronchiectasis. This should include past medical history, including childhood illnesses such as measles or whooping cough, history of pneumonia, TB and chest or sinus infections. A smoking history should be taken, and smoking cessation support offered to current smokers.

Including a drug history is important as respiratory symptoms are common side effects of some medications, including angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors which can cause a persistent dry cough, beta blocker, and non-steroid anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID)-induced bronchospasm (Table 2).

It is important to capture the frequency and severity of infections i.e., requiring admission. It is helpful to explore vaccination history as this may highlight immune system deficits, and infertility issues, which may be caused by ciliary disorders.

The duration and type of cough should be questioned, along with the quantity, consistency, and colour of sputum production. Some patients will also report foul tasting sputum especially during an infection. Breathlessness is common and should be measured using the modified Medical Research Council (mMRC) score.7 Clinical examination may reveal inspiratory basal crackles, wheeze and finger clubbing.

It is helpful to arrange baseline investigations to support the diagnosis of bronchiectasis, and exclude or identify alternative diagnoses. These should include:

- Routine blood tests

- Full blood count to identify possible anaemia and white cell abnormalities.

- Renal and liver function tests as poor function is associated with risk of infection.

- Glucose and HbA1c to exclude diabetes.

- Vitamin D level. Low levels of Vitamin D are associated with higher risk of infection.

- Sputum sample

- Sputum samples should be analysed for microbiology and culture to identify bacterial and mycobacterial infection.

- Radiological tests

- Chest X-ray may identify infection and abnormalities, including lung cancers. However, a normal chest X-ray cannot exclude the diagnosis of bronchiectasis.

- High Resolution Computerised Tomography (HRCT) scan is a highly accurate test,8 and is the gold standard test to confirm the diagnosis of bronchiectasis. You may – or may not – be able to arrange in primary care, but an HRCT scan is also helpful in determining the possible aetiology of bronchiectasis e.g., ABPA, and identifying which lobes are affected.

- Spirometry

- Spirometry is not particularly helpful in confirming the diagnosis of bronchiectasis but is useful to exclude obstructive and restrictive lung conditions e.g., asthma, COPD and interstitial lung disease,

- Pulse oximetry

- Hypoxia may be present in patients with severe bronchiectasis, and other conditions, and should be appropriately managed.

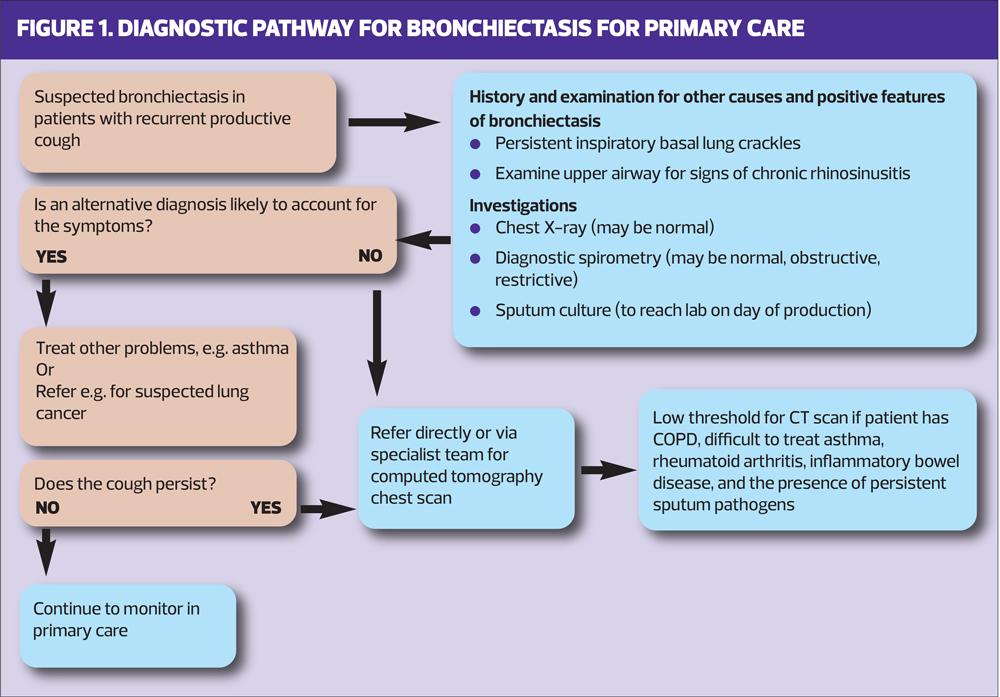

All patients with possible bronchiectasis should be referred to the respiratory specialist team to confirm the diagnosis, severity of the disease and develop a management plan for the patient. Figure 1 provides an example of a diagnostic pathway for primary care.6

Further investigations undertaken by specialists teams

The British Thoracic Society (BTS) guidelines make recommendations on the investigations that should be undertaken to support the diagnosis of bronchiectasis, and identify possible underlying cause(s) and co-existing conditions.

In addition to those performed in primary care, the specialist respiratory team will arrange further investigations, which may include:

- Radiology including HRCT if not previously performed. The HRCT scan is particularly helpful in identifying which area lobes of the lungs are affected, which can help with providing a targeted management plan.

- Blood test including:

- Aspergillus precipitins, total IgE, aspergillus IgE to exclude ABPA.

- Auto antibodies, Rheumatoid factor, anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide (anti–CCP) to exclude rheumatoid arthritis.

- Alpha 1 antitrypsin levels to exclude deficiency

- IgA, IgM, IgG and pneumococcal antibodies to review immune responses.

- Sputum analysis

- Microscopy, culture and sensitivity (MC&S) for common pathogens including Staphylococcus aureus, Haemophilus influenzae, Pseudomonas aeruginosa

- Early morning sputum (x3) for mycobacteria acid-fast bacilli and atypical mycobacteria

They will undertake a detailed clinical history to explore possible aetiology of bronchiectasis which could include:

- Undiagnosed cystic fibrosis, which would include the early onset of symptoms, a history of malabsorption, male infertility, childhood history of steatorrhoea, upper lobe disease, persistent isolation of Staphylococcus aureus in sputum samples.

- Ciliary dysfunction, which may present with a history of upper and lower respiratory tract infections, chronic sinus infections.

- Recurrent aspiration, which may be caused by dysphagia or gastro-oesophageal reflex disease and may be present without the patient experiencing classical symptoms e.g., indigestion, acid reflux.

The risk of exacerbations, hospitalisation and mortality should be assessed using the Bronchiectasis Severity Index,9 which is a useful tool to predict risks.

MANAGEMENT

Bronchiectasis is a long-term condition which can be managed in primary care, following the confirmation of the diagnosis. However, depending on the severity of the disease and treatment, some patients will continue to be followed up by respiratory specialists. The main aims of management are to prevent further lung damage, maximise lung function, improve quality of life and reduce exacerbations. This will include identifying and treating any underlying causes, including optimising co-existing lung conditions e.g., COPD or asthma. Important aspects of care to improve quality of life will include sputum clearance techniques, addressing breathlessness and reducing the risk of infections.

Patient education is essential to enable self-management, including routine treatment, how to recognise the signs of an infection or deterioration in their condition, and what actions they should take. The BTS has developed a self-management plan (https://www.brit-thoracic.org.uk/document-library/quality-standards/bronchiectasis/appendix-self-management-plan) which can be downloaded to support patients with bronchiectasis.

Sputum clearance

To reduce the risk of exacerbations, patients need to be able to effectively clear secretions from their chest. Therefore, patients should be referred to a specialist respiratory physiotherapist1, to be taught techniques to help mobilise and expectorate sputum.

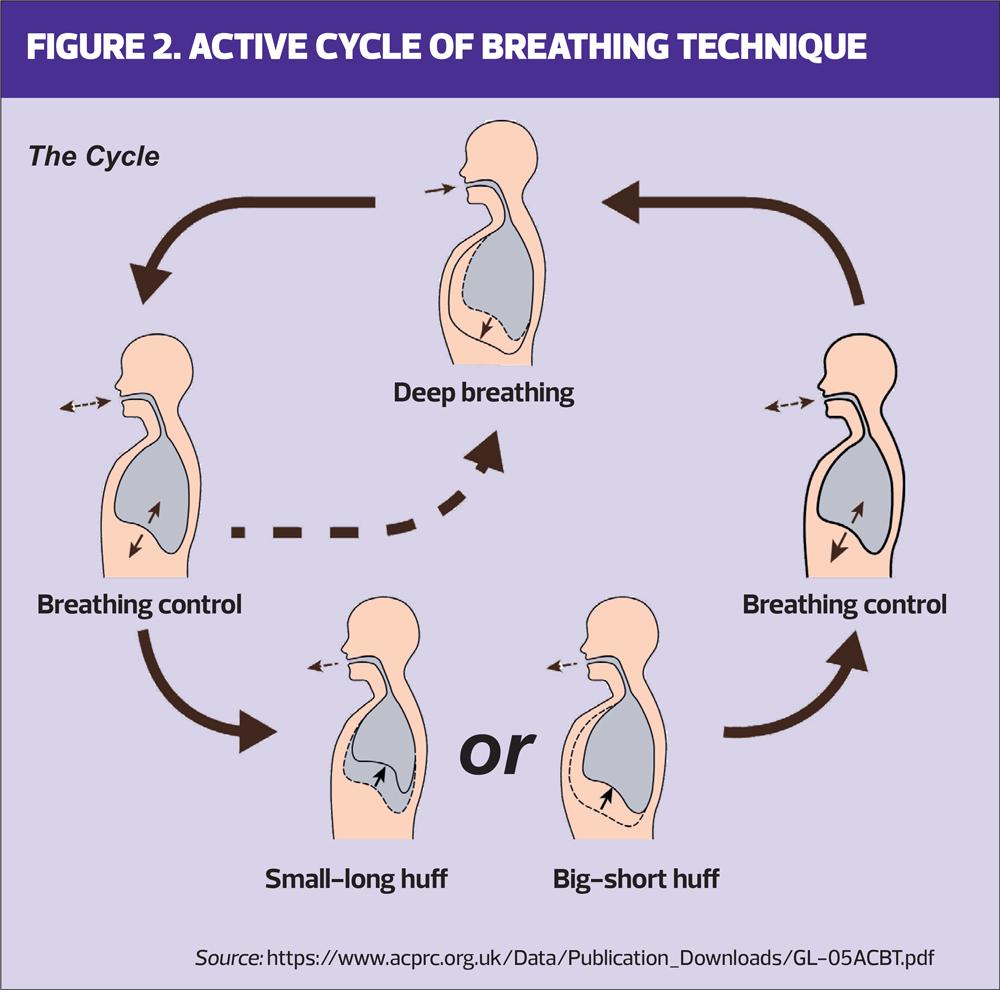

Common techniques include active cycle of breathing technique (ACBT) (Figure 2) and gravity assisted postural drainage to target specific lobes of the lung. If sputum is difficult to clear, the use of an oscillating positive pressure device maybe recommended. The combination of positive expiratory pressure with high frequency oscillations helps with expectoration. Sputum clearance techniques are effective, if practised regularly as part of a management plan. Many patients adapt quickly to including the techniques into their daily routines, but it is always sensible to check that they are undertaking them correctly.

Some patients may experience thick tenacious sputum. One of the commonest reasons for this is dehydration. Therefore, adequate fluid intake should be encouraged. Despite this, some patients may benefit from a trial of a mucolytic agent e.g., carbocysteine, or nebulised hypertonic saline to help reduce the viscosity of and loosen secretions.

Breathlessness

Patients should be referred to pulmonary rehabilitation if they have an mMRC >1, as it improves quality of life, breathlessness and reduces exacerbation rates.1 There is little evidence for the routine use of inhaled corticosteroids, short acting beta-2 agonists, long-acting beta-2 agonist (LABA) or long-acting anti muscarinic agents (LAMA), unless there is a coexisting obstructive lung disease, when recommended inhaled therapy should be offered.

However, a trial of LABA/ LAMA may be worth considering for significant breathlessness.6 In this situation, it is important to evaluate effectiveness and discontinue if there is no reported improvement in breathlessness.

Reducing infections

Reducing the risk of infections is vital and therefore patients should be offered and encouraged to have the pneumococcal and annual influenza and COVD vaccinations, in line with current guidance. If necessary, advice on shielding should be given along with practical tips of reducing exposure to viruses, such as hand hygiene, avoiding contact with people with coughs and colds, and wearing a face covering when in crowded spaces.

Exacerbations

Unfortunately, patients may experience exacerbations, and early intervention is important.

The classical signs of an infection include:

- Generally feeling unwell

- Increase in cough and breathlessness

- Change in sputum volume, colour, and viscosity. Some patients may experience episodes of haemoptysis

- Pyrexia

An exacerbation can mild and managed with an increase in sputum clearance techniques, hydration and rest, but often will require a course of antibiotics. Typically, a prolonged course i.e., two weeks, is required to address the underlying infection. Patients should be issued with sputum pots to produce a sputum sample, if they have not responded to initial treatment. Clear guidance should be provided in the patient’s management plan on when to seek medical help.

It is recommended that patients who experience three or more exacerbations a year should be referred for specialist review. They may require prophylactic antibiotics e.g., azithromycin or nebulized antibiotics to address the frequency of exacerbations. The patient should be reviewed regularly by the specialist team.

COMPLICATIONS

People with mild bronchiectasis can expect to have normal life expectancy. However, some people will experience complications, which include:

- Frequent exacerbations

- Haemoptysis

- Anxiety and depression

- Incontinence

- Fatigue

- Chest pain

- Respiratory failure

REVIEW

It is recommended that patients with bronchiectasis are reviewed at least annually.1

The review should include:

- Review of pneumococcal, annual influenza, COVID 19 vaccinations status

- Exacerbation history (consider referral to respiratory specialists)

- Compliance with sputum clearance techniques (re-refer to specialist respiratory physiotherapy if necessary). If the patient has been issued with oscillating positive pressure device, this should be replaced annually

- Assessment of co-morbidities, such as asthma and COPD and optimise if necessary

- Pulse oximetry and spirometry (for evidence of disease deterioration and existing airway disease)

- Update the patient’s management plan if required

Although health related quality of life questionnaires are not routinely used in clinical practice,10 disease/symptom specific questionnaires e.g., COPD Assessment Test11 or Leicester Cough Questionnaire,12 can be helpful to measure the impact of symptoms and effectiveness of interventions.

CONCLUSION

Bronchiectasis is a relatively common condition that can significantly affect the quality of life of people living with it. Following the confirmation of the diagnosis, most cases can be managed in primary care with good symptoms management, education and self-management strategies, prompt treatments of exacerbations and regular reviews.

REFERENCES

1. Hill A, Sullivan A, Chalmers J, et al. British Thoracic Society guideline for bronchiectasis in adults. Thorax 2019; 74 (Suppl 1): 1–69 doi:10.1136/thoraxjnl-2018-212463

2. King P. The pathophysiology of bronchiectasis. International Journal of COPD 2009; 4 411-419 doi:10.2147/copd.s6133

3. Quint J, Millett E, Joshi M, et al. Changes in the incidence, prevalence, and mortality of bronchiectasis in the UK from 2004 to 2013: a population-based cohort study. Eur Respir J 2016; 47 (1) 186–193. doi: 10.1183/13993003.01033-2015

4. King P, Holdsworth SR, Freezera NJ, et al. Characterisation of the onset and presenting clinical features of adult bronchiectasis. Respiratory Medicine 100 (12), 2183-2189 doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2006.03.012

5. Gao Y, Guan W, Shao-xia L, et al. Aetiology of bronchiectasis in adults: A systematic literature review. Respirology 2016; 21 1376-1383 doi: 10.1111/resp.12832

6. Gruffydd-Jones K, Keely D, Knowles V, et al. Primary care implications of the British Thoracic Society Guidelines for bronchiectasis in adults. NPJ Prim Care Respir Med 2019; 29: 24. doi: 10.1038/s41533-019-0136-8

7. Mahler DA, Wells CK. Evaluation of clinical methods for rating dyspnea. Chest 1988 Mar 1;93(3):580-6 doi: 10.1378/chest.93.3.580

8. Young K, Kolbenstvedt. High resolution CT and bronchography in the assessment of bronchiectasis . Acta Radiol 1991;32:439-441

9. Chalmers JD, Goeminne P, Alberti S, et al The Bronchiectasis Severity Index: an international derivation and validation study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2014;189(5);576-585 doi: 10.1164/rccm.201309-1575OC

10. McLeese R, Spinou A, Alfahl Z, et al. Psychometrics of health-related quality of life questionnaires in bronchiectasis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Respir J 2021; 58: 2100025 doi: 10.1183/13993003.00025-2021

11. Jones PW, Harding G, Berry P, et al. Development and first validation of the COPD assessment test. Eur Respir J 2009; 34: 648–654 doi: 10.1183/09031936.00102509

12. Birring SS, Prudon B, Carr AJ, et al. Development of a symptom-specific health status measure for patients with chronic cough: Leicester Cough Questionnaire (LCQ). Thorax 2003; 58(4):339-343 doi: 10.1136/thorax.58.4.339

Related articles

View all Articles