Bedwetting: A guide for practice nurses

Davina Richardson RGN/RSCN BSc (Hons)

Davina Richardson RGN/RSCN BSc (Hons)

Children’s Specialist Nurse, Bladder & Bowel UK

This article has been initiated and supported, and reviewed solely by ALTURiX Ltd.

Practice Nurse September-October 2023;53(5)

Myths and misunderstandings about nocturnal enuresis – bedwetting – continue to linger from the days when it was considered something that children would simply grow out of: it is a treatable condition and general practice nurses should provide accurate and timely advice and intervention when it is reported

Bedwetting, nocturnal enuresis, or simply enuresis, are different terms used to describe a common but distressing disorder, that may have a significant impact on school performance, social and psychological functioning for the child, and on quality of life for them and their family.1

Considered a medical condition of ‘intermittent incontinence that occurs during periods of sleep’ once a month or more for at least three months, in those aged over five years,2 it affects about 5–10% of seven-year-olds and 3% of teenagers.3 Numbers reduce with increasing age. However, prevalence continues at about 2% in adulthood. Those who are wetting most frequently can be assumed to have the most significant and enduring negative impacts and are known to be least likely to experience spontaneous resolution of symptoms.4

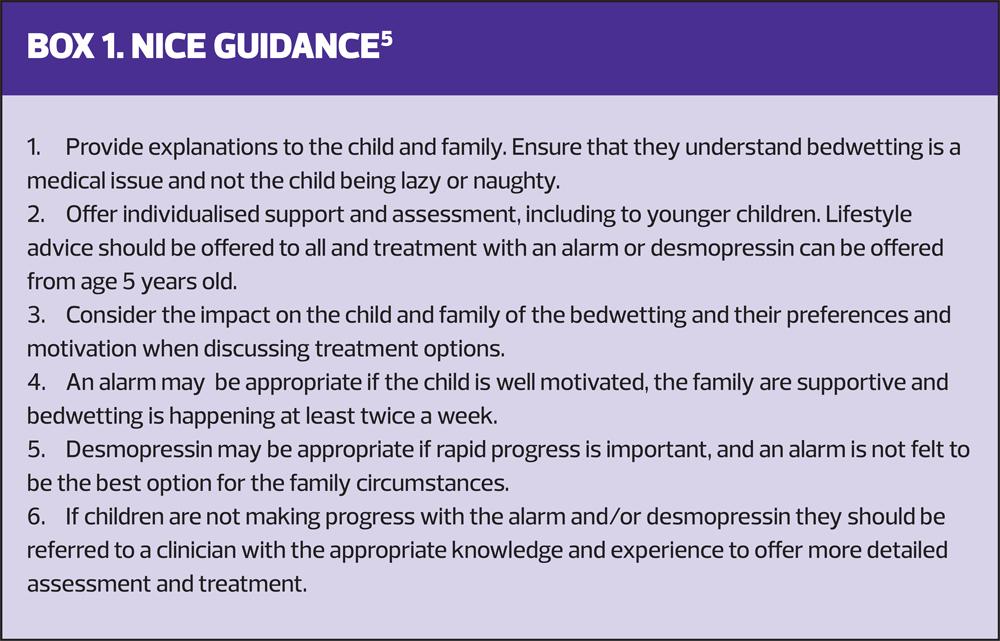

Research has increased understanding of this heterogenous condition and there has been guidance for management from NICE for more than a decade (Box 1).5 However, myths and misunderstandings continue to linger from the days when it was considered a self-limiting psychological condition.

It is important for primary care health professionals to understand the impact, causes, comorbidities and treatment options for bedwetting, to be able to provide timely and effective support and/or appropriate onward referral to affected children and young people. This will help improve quality of life for the whole family, identify and intervene appropriately for any comorbidities and reduce negative outcomes for the affected child.

IMPACT

The sense of shame, the social stigma of a continence issue and fear of bullying results in children and young people harbouring a burdensome secret, which in turn causes feelings of difference and increases social isolation.6 Many respond by avoiding social situations that involve sleeping away from home. Bedwetting has been described as ‘creating a sense of struggle’; of being a problem hidden within the family during childhood and one where young adults choose social isolation and avoidance of intimate relationships to cope.7

Associated stress for parents may be one of the reasons why some respond punitively to their children. Ferrara et al1 found this to be the case with 54.1% of parents of a large sample of Italian families who mainly told their children off for being wet, but also used discipline, humiliation, sleep deprivation and corporal punishment. Sá et al8 reported that all 87 children in their study of children whose parents had also wet the bed had been punished, despite this being an unhelpful response that may increase the wetting.9

Clinical experience is that most children with bedwetting have supportive and concerned families. However some do respond with punishment due to a lack of understanding of the causes of bedwetting and that it is not a behavioural issue. It is important for the child’s wellbeing, and for engagement with treatment, that both the child and family are given appropriate explanations about the condition.

CAUSES

Bedwetting is known to run in families. However, genetic links do not indicate the causes for the individual, duration of the condition or response to treatment.10 NICE5 describes bedwetting as ‘a symptom that may result from a combination of different predisposing factors.’ The three systems model of enuresis remains an accepted description of enuresis, that outlines the main causes: nocturnal polyuria, and/or bladder overactivity during sleep, combined with an inability to wake to bladder signals.11

Inability to reduce urine production overnight is linked to reduced production of vasopressin at night. (Vasopressin is the hormone that increases reabsorption of water in the kidney tubules.) However, this does not explain why children who have nocturnal polyuria are not able to wake to the full bladder signals, which provide strong arousal stimuli.10 Furthermore, not all children who are wet at night produce more urine during sleep than would be expected. Many appear to have bladder overactivity during sleep, with the volume of urine passed during the wetting incident being lower than expected bladder capacity for age.12

One of the myths associated with enuresis is that the affected child sleeps deeply. However, although studies have found that children with enuresis are difficult to arouse from sleep, they are more tired in the day than their peers, with poorer sleep quality at night that affects their daytime functioning and wellbeing.1,13 Children with bedwetting have disturbed sleep associated with poorer quality of life, and treatment improves neuropsychological functioning.13,14

COMORBIDITIES

There are several comorbidities that are associated with enuresis and enuresis is occasionally a symptom of other conditions. Sudden onset of bedwetting after a period of being dry should be investigated and underlying pathology including diabetes mellitus, urinary tract infection and polyuric renal failure should be excluded.3

Children with developmental differences including autism and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder are more likely to have enuresis than children with typical development and are more likely to be resistant to treatment.15,16 However they should still be offered the same individualised care options as their typically developing peers.17

Constipation has an association with enuresis, although often unrecognised by families.18 Clinical experience is that if this is missed, treatment success is less likely. The rationale is that the retained stools distend the rectum causing pressure on the bladder. They may also trigger detrusor overactivity, which may produce daytime symptoms, including frequency, urgency and daytime urinary incontinence.19 Constipation and daytime lower urinary tract symptoms should be assessed and treated, although their absence does not exclude the latter problem occurring only during sleep.

Sleep disordered breathing should always be considered. It is thought that, if present, the frequent arousal stimuli from the upper airways make the child less able to wake to bladder signals. Resolution of the airway issues may result in spontaneous remission of the bedwetting. Therefore, if families report snoring or sleep apnoea they should be referred to the appropriate specialist for assessment and treatment.20

The significant impact and potential for comorbidities alone should be sufficient to result in initiation of assessment and proactive treatment, when the child and family present. However, enuresis has also been linked to nocturia in adulthood.21,22 Although it is not yet clear whether early resolution of bedwetting reduces the likelihood of this, the possibility adds further weight to the argument for intervention. It is also worth noting that children with additional needs, including those with learning disabilities who are continent in the day, can and should be offered the same individualised assessment and treatment for bedwetting as children who have typical development.

INITIAL ADVICE

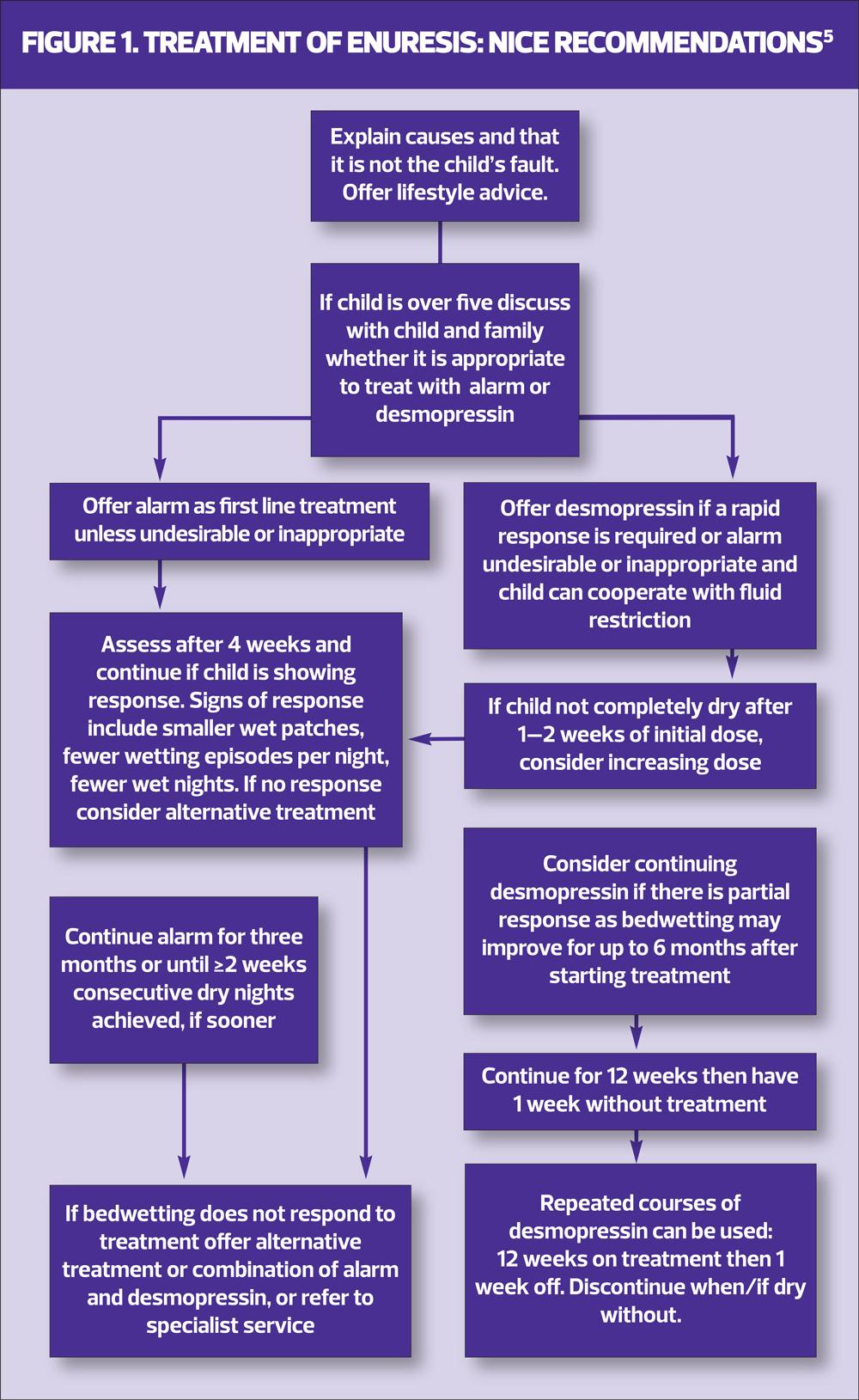

Initially advice may be offered whenever a child presents, including in children under five years old.5 Understandable explanations for the cause of the problem should be provided, to reduce the likelihood of punishment and to encourage adherence to treatment.

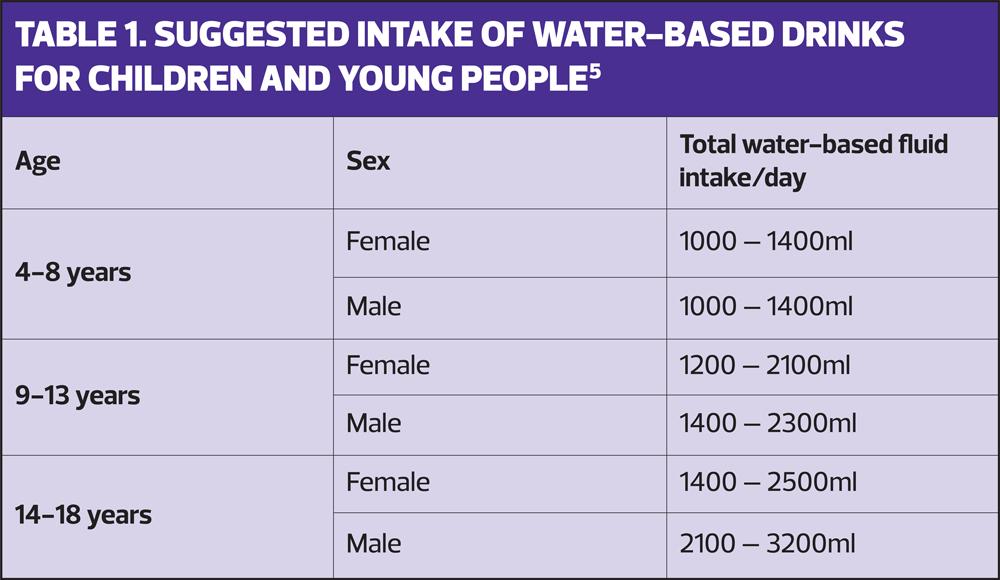

It is usual to exclude and treat any underlying constipation, in line with NICE guidance,23 and encourage behaviours that promote optimal bladder function, as these may lead to resolution for a minority of children. The child should be encouraged to drink water-based fluids at approximately two hourly intervals from waking until an hour before bedtime (see Table 1 for suggested fluid intake). They should avoid caffeinated and fizzy drinks as these may promote diuresis and bladder overactivity. Optimal toileting habits – using the toilet about every two hours and just before settling to sleep – should also be recommended. Ensuring a good position on the toilet with bottom and thighs well supported will help to facilitate complete bladder emptying.3

Protein and salt increase diuresis, so should be avoided in the evening.24 Families should be advised that waking their child to toilet at night is unlikely to be helpful in the long term and should be avoided.3

Many families use containment products (disposable pants or nappies) as a management strategy. NICE suggests a trial without these, but does not provide further information. Breinbjerg25 found that 13% of untreated children aged 4–8 years old, in a cohort of 70, became dry within two weeks when they stopped using disposable products at night. The recommendation is that if children continue to be wet, use of products may improve the child’s and their parent’s sleep, emotional wellbeing and quality of life. It is therefore reasonable to use them if the child and family desire this, until the wetting starts to resolve.

Some children will see progress with the above advice. However, there is evidence that basic toileting advice alone is ineffective for children with bedwetting.26 For those that do not have a rapid reduction in wet nights after being provided lifestyle advice more proactive treatment should be offered.

PROACTIVE TREATMENT

There are two main options for first-line treatment of bedwetting. These are the enuresis alarm and desmopressin. Information about both options should be provided, with the child and family supported to choose the most desirable and appropriate for their situation to try first.

Enuresis alarm

The alarm is not widely available for loan, other than from children’s community bladder and bowel services. However, some families may opt to purchase one. The alarm is not suitable or desirable in all situations, including where there are safeguarding concerns. If parents are expressing negativity, anger or lack of understanding towards their child that persists with explanations, if there is neglect, physical or emotional abuse, the alarm disturbing the parent’s sleep may trigger exacerbation of parental negative behaviours towards their child, increasing the likelihood of the chid suffering significant harm. Using an alarm has been likened to having a new baby: it may make a noise at any time of the night and most children need parental support to use it, at least initially, which impacts on sleep for the child and their family and may result in difficulties with adherence.

The alarm is likely to be most effective for those who are motivated, have parental support, who use it every night and who are wet two or more nights a week at commencement of treatment.3 It can be successful in those with learning disabilities and should not be excluded because of autism or ADHD. There are no predictors for success with an alarm. However, if there is no progress or poor adherence after four weeks of treatment, it is unlikely to lead to dryness at that point and should be discontinued,27 at least for a time.

If an alarm is used, it is important that it is used every night, although it does not need to be reset after the first sounding, even if the child is wet again. Parents need to wake their child as soon as they hear the alarm.3 The child should the turn off the alarm and go straight to the toilet to try to void (before any wet linen is changed) and before settling back to sleep. Signs of progress include the child learning to wake to the alarm, the alarm sounding after a longer period of sleep, the child managing to pass some urine in the toilet and dry nights. If none of these are seen within four weeks the alarm should be discontinued.27

If progress is made, the child should continue to use the alarm until they have achieved 28 consecutive dry nights or improvements have not continued after a further two to three months of alarm use. If the alarm does not resolve the problem, it remains an option for a later date, alone or in combination with other treatments, but alternative strategies should be considered.

Desmopressin

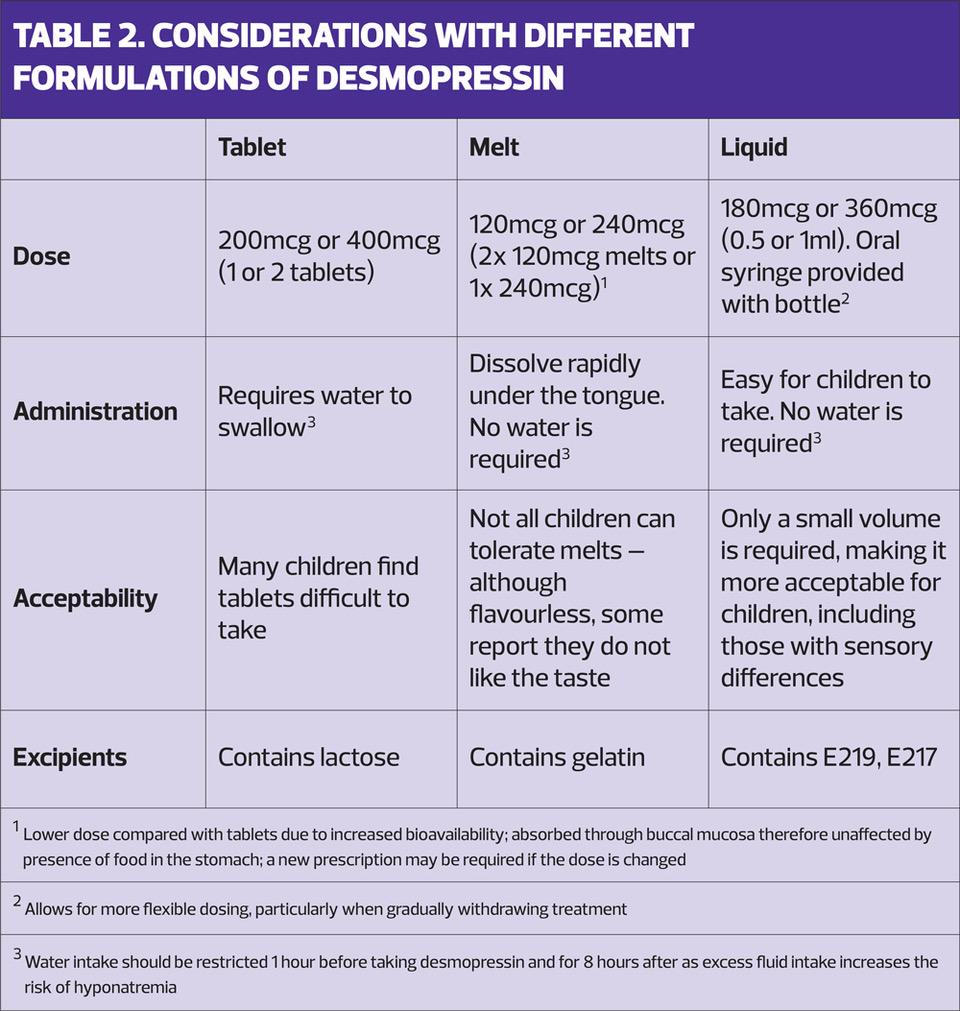

Desmopressin, the other first-line treatment, is a synthetic form of the hormone arginine vasopressin. It reduces urine output so that the bladder can accommodate the total volume produced, in children with nocturnal polyuria, without the child needing to wake. Desmopressin is available as a 200mcg tablet, an oral solution of 360mcg per 1ml, or as a 120 or 240mcg oral lyophilisate (melt). It is usual practice to start with 200mcg if tablets are used, 180mcg for liquid and 120mcg for the lyophilisate and double the dose after a week if the wet nights continue (See Table 2).

Desmopressin is not associated with any safety concerns, and side effects, which include but are not limited to hyponatraemia, nausea, abdominal pain, emotional changes and vomiting, are rare. Contraindications include cardiac insufficiency, treatment with diuretics, a history of hyponatraemia, inappropriate ADH secretion and von Willebrand’s Disease Type IIB.

Desmopressin is given up to an hour before bedtime. However, fluid intake must be restricted in the one hour prior to taking it, with no fluids for eight hours afterwards, to prevent hyponatremia, which may occur with excess fluid intake. It has been suggested that up to 200mls in the first hour after administration is a safe limit.3 Desmopressin must not be given if the child cannot comply with the fluid restriction prior to administration for any reason. It should also be omitted if the child is unwell with diarrhoea or vomiting, until they have recovered.28

Response to desmopressin is usually immediate, but it is advisable to use it for at least 1–2 weeks to gauge its effect. If it is not fully effective, the dose can be doubled i.e. 400mcg for the tablets, 360mcg for the liquid and 240mcg for the lyophilisate. If wetting reduces or if the child is dry when taking desmopressin it may be continued for up to 12 weeks at a time. The child must then have one week without it. If they are dry during the treatment break it does not need to be resumed. If wetting returns, desmopressin may be restarted for further 12-week treatment blocks.24

Consideration should be given to gradual weaning of desmopressin if there is relapse after a previous response.5 This may be done via dose reduction, which may be easier with the liquid formulation, or a structured or random withdrawal: families may be advised to reduce the dose to six days a week for two weeks then five days a week etc, or it might be suggested that they throw a dice and give desmopressin if it lands on numbers 1-3 and withhold it if the dice lands on numbers 4-6. They should keep a diary of desmopressin administration and of wet and dry nights for evaluation.

CHOOSING TREATMENT

The mode of action of the alarm is not fully understood, but this treatment may be more acceptable to families and children who are motivated to overcome the issue and cope with associated disrupted nights and/or are reluctant to try pharmacological remedies first. Furthermore, most children who become dry with an alarm sleep throughout the night without needing to use the toilet10 and are more likely to remain dry permanently.

It is known that children with nocturnal polyuria are likely to respond to desmopressin,29 and it is a straightforward therapy, but its success cannot be accurately predicted. It should therefore not be excluded for any child. As desmopressin comes in different formulations a discussion should be had about which is likely to be most appropriate and acceptable, although resource implications in terms of cost to the NHS should also be considered.

Tablets are usually swallowed with water, which may be an issue for two reasons: water should be avoided in the hour prior to taking desmopressin and the eight hours after, to prevent hyponatremia. Furthermore, even a small amount of water before bed may contribute to earlier bladder filling, particularly for younger children with smaller bladder capacities,30 and clinical experience is that parents and younger children often prefer to avoid tablets if possible.

The melts were formulated for ease of administration to children and have been found to increase adherence and hence efficacy.30 They are simple to administer and take but must be discarded if broken into more than two pieces. However, anecdotally a small minority of children, particularly those who have sensory hypersensitivities, have complained about a residual taste.

The oral solution of desmopressin is newly available and provides a cost-effective alternative to tablets and melt. It is flavourless and only small volumes are required, which makes it straightforward to swallow and more difficult to spit out. It is also a familiar way of taking medication for many children, and does not contain any common allergens.

The child and family should be provided with sufficient information about each treatment option and allowed to choose which to try first. If the bedwetting does not resolve with the first option chosen, an alternative may be appropriate. It is worth bearing in mind that different formulations of desmopressin may induce different responses in the individual, so are worth trying, particularly if medication remains the preferred option although families may opt to try a different treatment (alarm if they have previously tried desmopressin and vice versa.

It is important for those offering initial intervention and support to be aware that up to half of affected children have treatment resistance or relapse.31 Clinical experience is that further treatment with options previously used, or a different formulation of desmopressin, or combination of both alarm and desmopressin may be successful. However, if there is occult constipation, overactive bladder during waking hours or other comorbidities, the bedwetting may not improve.

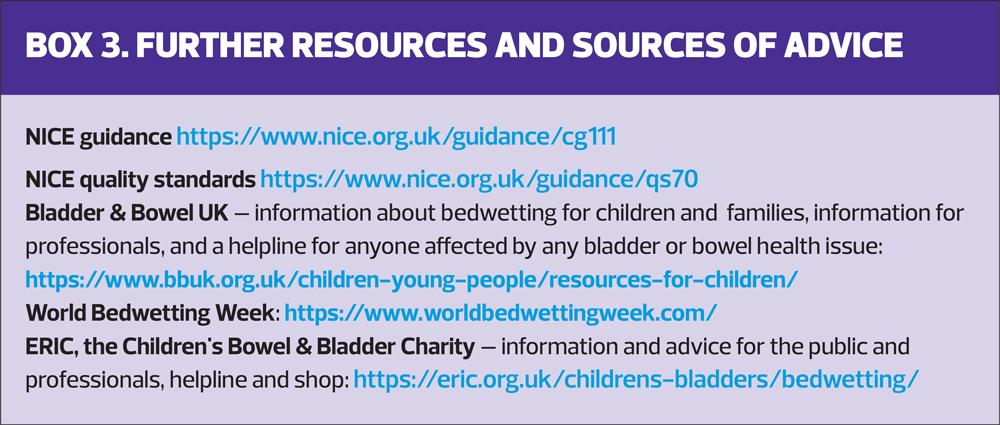

Further resources are available to children, families as well as to clinicians (see Box 3), which may aid understanding and adherence. However, if children are not making progress after treatment with desmopressin and/ or alarm, for any reason, NICE5 is clear that children should be referred to a professional with the appropriate expertise for further assessment and support.

CONCLUSION

Bedwetting is a common and distressing condition for both children and their families, that is not often self-limiting, particularly in those who are wet frequently. For this reason, delaying active intervention is not defensible, including in children with additional needs or disabilities. Assessment, followed by lifestyle advice should be offered to all and initial treatment options discussed for those who are over 5 years old. If the response to intervention is limited then children should, in line with NICE guidance, be referred to a specialist service.2

Job code: DM022 Date of preparation: September 2023 This article has been initiated and supported and reviewed solely by ALTURiX https://alturix.com/contact-us/ Prescribing information for DEMOVO® is available here. Reporting adverse effects: Adverse events should be reported. Reporting forms and information can be founds at https://yellowcard.mhra.gov.uk or search for MHRA Yellow Card in the Google Play or Apple App Store. Adverse events should also be reported to Alturix Limited at safefy@alturix.com and +44 (0)1903 038 083 |

REFERENCES

1. Ferrara P, Francheschini G, Bianchi di Castelbianco, et al. Epidemiology of enuresis: a large number of children at risk of low regard. Italian Journal of Pediatrics 2020;46(128): doi.org/10/1186/s13052-020-00896-3

2. Austin PF, Bauer SB, Bower W, et al. The standardization of terminology of lower urinary tract function in children and adolescents: update report from the Standardization Committee of the International Children’s Continence Society. Neurourology and Urodynamics 2016;35:471- 481

3. Nevéus T, Fonseca E, Franco I, et al. Management and treatment of nocturnal enuresis – an updated standardization document from the International Children’s Continence Society. Journal of Pediatric Urology 2020;16:10-19

4. Van Herzeele C, Vande Walle J, Dhondt K, Juul KJ. Recent advances in managing and understanding enuresis. F1000Research 2017:6:1881 doi:10.12688/1100research.11303.1

5. NICE CG11. Bedwetting in under 19s; 2010. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg111

6. Whale K, Cramer H, Joinson C. Left behind and left out: the impact of the school environment on young people with continence problems. Br J Health Psychol 2018;23(2): 253 – 277

7. Wilson GJ. The lived experience of bedwetting in young men living in Western Australia. Australian and New Zealand Continence Journal 2014; 20 (4) 188 – 192

8. Sá CA, Gusmão Paiva AC et al. Increased risk of physical punishment among enuretic children with family history of enuresis. J Urol 2016;195(4 Pt 2):1227-30

9. Al-Zaben FN, Sehlo MG. Punishment for bedwetting is associated with child depression and reduced quality of life. Child Abuse and Neglect 2015;43:22-29

10. Nevéus T. Pathogenesis of enuresis: Towards a new understanding. Int J Urol 2017;24:174-182

11. Butler RJ, Holland P. The three systems: a conceptual way of understanding nocturnal enuresis. Scand J Urol Nephrol 2000;34(4):270-277

12. Nevéus T. The amount of urine voided in bed by children with enuresis. J Pediatr Urol 2019;15:31 e1-e5

13. Van Herzeele C, Dhondt K, Roels SP, et al. Periodic limb movements during sleep are associated with a lower quality of life in children with monosymptomatic enuresis. Eur J Pediatr 2015;174:897-902

14. Van Herzeele C, Dhondt K, Roels SP, et al. Desmopressin (melt) therapy in children with monosymptomatic nocturnal enuresis and nocturnal polyuria results in improved neuropsychological functioning and sleep. Pediatr Nephrol 2016;31:1477–1484

15. Van Herzeele C, Vande Walle J. Incontinence and psychological problems in children: a common central nervous pathway? Pediatr Nephrol 2016; 31, 5, 689 – 692

16. Von Gontard A, Equit M. Comorbidity of ADHD and incontinence in children. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2015;24:127–140

17. Nevéus T. Problems with enuresis management a personal view. Front Pediatr 2022;10: doi10.3389/fped.2022.1044302

18. McGrath KH, Calwell PHY, Jones MP. The frequency of constipation in children with nocturnal enuresis: a comparison with parental reporting. J Pediatr Child Health 2008;44:19–27

19. Nevéus T. Nocturnal enuresis – theoretic background and practical guidelines. Pediatr Nephrol 2011; 26: 1207 -1214

20. Zaffanello M, Piacentini G, Lippi G, et al. Obstructive sleep-disordered breathing, enuresis and combined disorders in children: chance or related association? Swiss Med Wkly 2017;147(0506):w14400

21. Gong S, Khosla L, Gong F, et al. Transition from childhood nocturnal enuresis to adult nocturia: A systematic review and meta-anlaysis. Res Rep Urol 2021;13:823–832

22. Goessaert AS, Schoenaers B, Opdenakker O, et al. Long-term follow up of children with nocturnal enuresis: increased frequency of nocturia in adulthood. J Urol 2014:191:1866–1871

23. NICE CG99. Constipation in children and young people: diagnosis and management; 2010. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg99

24. Vande Walle J, Rittig S, Bauer S, et al Practical consensus guidelines for the management of enuresis. Eur J Pediatr 2012;171(6):971–983

25. Breinbjerg A, et al. The Effects of Discontinuing Night-time Protection on Incidence of Paediatric Nocturnal Enuresis – a Multicentre Randomised Controlled Trial. Poster 4, presented at Association for Continence Advice Conference 15 – 16 May 2023, Birmingham

26. Borgström M, Bergsten A, Tunbjer M, et al Daytime urotherapy in nocturnal enuresis: a randomised controlled trial. Arch Dis Child 2022;107:570–574

27. Larsson J, Borgström M, Karanikas B, Nevéus T. The value of case history and early treatment data as predictors of enuresis alarm response. J Pediatr Urol 2022;19(2):173.e1-173.e7

28. NICE BNF. Desmopressin; 2023. https://bnfc.nice.org.uk/drugs/desmopressin/#medicinal-forms

29. Van Herzeele C, Evans J, Eggert P, et al. Predictive parameters of response to desmopressin in primary nocturnal enuresis. J Pediatr Urol 2015;11(4): 200.e1–200.e8

30. Juul KV, Van Herzeele C, De Bruyne P, et al. Desmopressin melt improves response and compliance compared with tablet in treatment of primary monosymptomatic nocturnal enuresis. Eur J Pediatr 2013;172:1235–1242

31. Caldwell PHY, Lim M, Nankivell G. An interprofessional approach to managing children with treatment-resistant enuresis: an educational review. Pediatr Nephrol 2018;33:1663-1670

Related articles

View all Articles