Management of COPD symptoms: the role of mucolytics

TERRY ROBINSON

TERRY ROBINSON

RGN DipN (Community Nursing)

MSc BSc NMP

Respiratory Nurse Consultant

Harrogate and District NHS Foundation Trust

Practice Nurse 2022;52(2):16-21

This article has been initiated and supported by Alturix Ltd, who have had the opportunity to review it for factual accuracy but have had no input into its content.

Sputum production is a common feature of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) but for some patients, it is difficult to clear, leaving them potentially vulnerable to respiratory infections. We look at the evidence for mucolytic therapies and when they should be considered

COPD affects up to 3 million people in the UK, although only a third of these – just over a million – have been currently diagnosed.1,2 This means that there are a lot of ‘missing’ patients who remain symptomatic, living with symptoms and disability. Around a third of patients are only diagnosed following a first admission to hospital with an exacerbation.3,4

SYMPTOMS

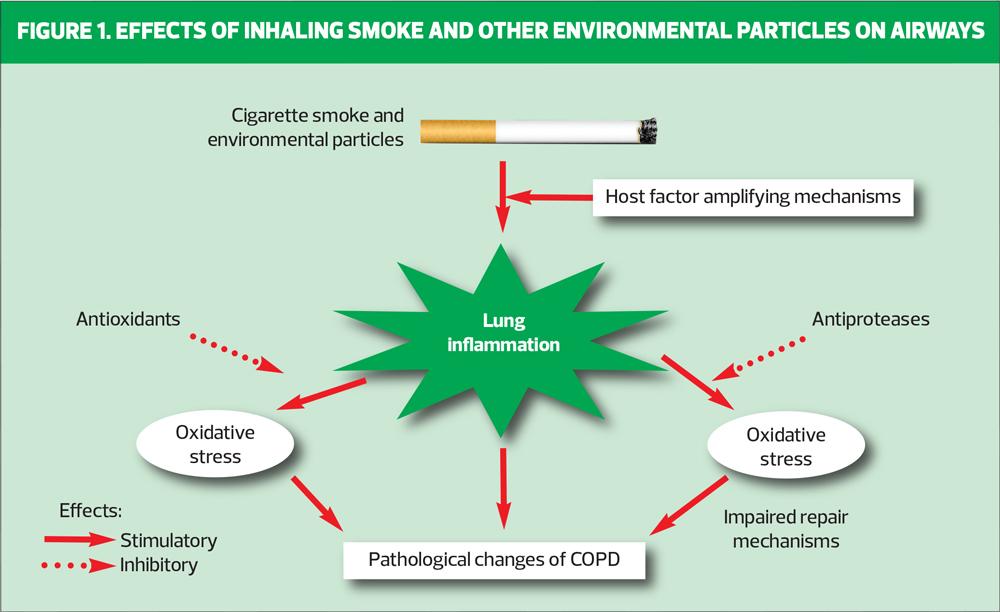

Symptoms of COPD develop due to airway inflammation, causing narrowing and obstruction of the airways. This results in airflow limitation and air trapping which subsequently leads to poor gas transfer and ultimately respiratory failure.1,3

Although breathlessness is the most common symptom in COPD,3 some patients have a productive cough, caused by hypersecretion of the mucus glands in the airways, and occasionally wheeze and or chest tightness, again caused by narrow airways.

The obstruction in the airways, unlike asthma, is irreversible and usually progressive over time.

You should suspect COPD in patients who are symptomatic, over the age of 35, and usually with a 20-pack year smoking history and/or an occupational history of working with noxious fumes or gases.

GUIDELINES

The main guidelines available to help clinicians diagnose and treat patients with COPD are the Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) report,1 and the clinical guideline from NICE (NG 115)3 and, in Scotland, the Best Practice guide.2

In both the GOLD report and NICE guidelines, non pharmacological therapies, such as smoking cessation, influenza, pneumococcal and COVID-19 vaccinations, and pulmonary rehabilitation are recommended.1,3 Both guidelines also state that long-acting bronchodilators are the cornerstone of maintenance treatment. For some patients, if they are demonstrating features of asthma, or are having frequent exacerbations, inhaled corticosteroid treatment (ICS) is recommended.

CHRONIC BRONCHITIS

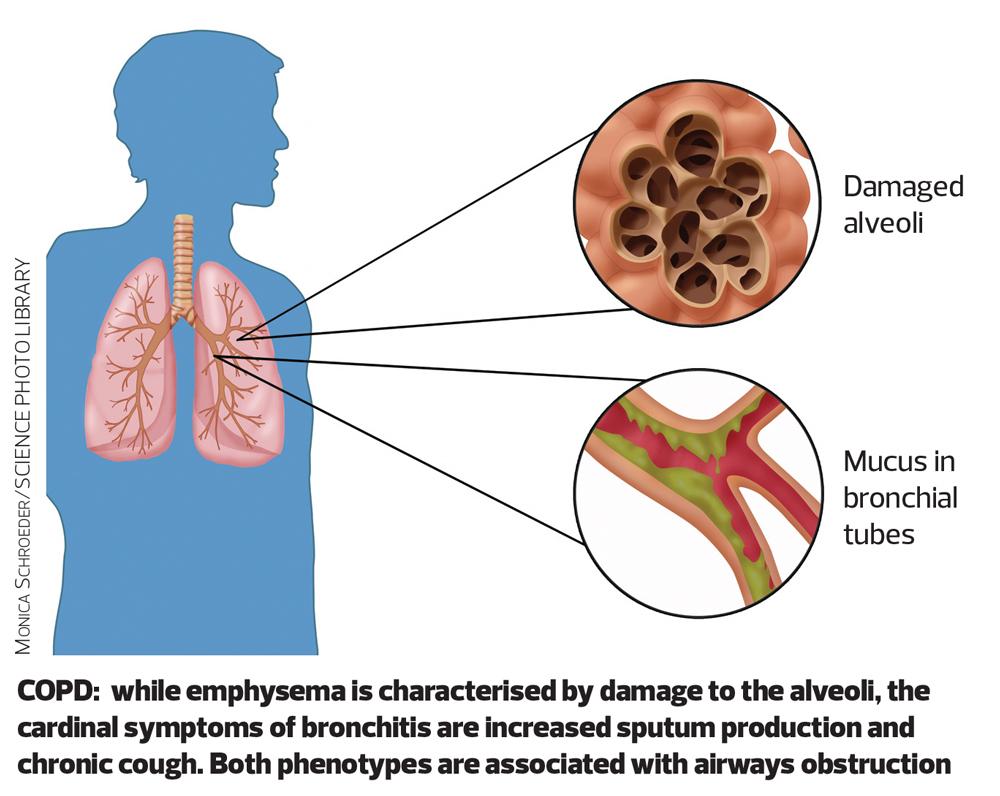

COPD is an umbrella term for emphysema and chronic bronchitis. The two phenotypes can also overlap, and some patients can have both emphysema and chronic bronchitis.

To diagnose chronic bronchitis patients will have a productive cough for at least 3 months of the year for 2 consecutive years,4 but the reality is that most patients cough every day throughout the year.

About a third of patients with COPD will have the chronic bronchitis phenotype and studies have shown that those patients with chronic bronchitis lose lung function, as defined by Forced Expiratory Volume in 1 second (FEV1), faster than those without, and that the death rate is higher in this patient group.4

Many of these patients develop respiratory failure and need long term oxygen therapy.4

Patients with chronic bronchitis tend to have worse health status than those with emphysema, and worryingly, younger patients, such as those under the age of 50 diagnosed with chronic bronchitis, are at a higher risk of morbidity and mortality when compared with those without bronchitis.4

Emphysema is pathologically defined as an abnormal permanent enlargement of air spaces distal to the terminal bronchioles, accompanied by the destruction of alveolar walls and without obvious fibrosis. This process leads to reduced gas exchange, changes in airway dynamics that impair expiratory airflow, and progressive air trapping.5

MUCUS SECRETION

The reason why we have goblet cells, which secrete mucus on to the mucous membrane of the airways, is to act as a barrier against particles and micro-organisms we may have inhaled and is part of the lung defence system.6 Goblet cells, and therefore mucus production, are significantly increased when the epithelium is irritated, for example, by inhaling cigarette smoke and other noxious fumes.

In normal circumstances, approximately 20-30ml of secretions are produced by the airways every day. We have a ‘mucociliary escalator’ made of beating cilia that brush the mucus upwards from the bronchus, and away from the airways.7

These secretions are often swallowed. If the quantity of mucus exceeds 30mls, a cough is necessary to clear the airways of the mucus. We have cough receptors around the trachea and pharynx, which are there to induce a cough to expel the excessive mucus. Patients with chronic bronchitis have impaired mucociliary clearance and this is associated with increased vulnerability to respiratory tract infections.7

Other respiratory conditions are also associated with difficulty in expectorating mucus, for example, bronchiectasis, where there is damage to the epithelium and the cilia are destroyed8 and cystic fibrosis, where the mucus can become dehydrated, making it so thick and sticky that the cilia are unable to propel the mucus upwards from the airways.9

Factors that can inhibit the mucociliary escalator include cigarette smoke and inhalation of toxic gases, which can cause abnormalities in the cilia and impair motility.10

MUCOLYTICS

Now we understand the mechanisms of chronic bronchitis and mucus production where do mucolytic therapies come in?

Evidence base

An independent Cochrane review11 was carried out in 2019. The review compared mucolytic agents versus placebo in patients with chronic bronchitis or COPD. The primary objective was to determine whether, if patients were prescribed a mucolytic, there would be a reduction in exacerbations and/or days of disability. Secondary objectives included whether there was any improvement in lung function or quality of life.

Finally, the review looked at the frequency of adverse events associated with the use of mucolytics.

The review looked at 38 different trials, involving over 10,000 participants. Most of the studies looked at the use of N-acetylcysteine (NAC) rather than carbocisteine. Some of the studies looked at mucolytics not available to prescribe in the UK. None of the studies were head-to-head between acetylcysteine and carbocisteine.

The key results from the studies found that patients prescribed a mucolytic were more likely to be exacerbation-free compared with those given placebo. The number needed to treat (NNT) was low, at only 8 to keep a patient exacerbation-free for an average of 9 months.

This compares favourably to the NNT of 14 patients on an ICS/LABA combination inhaler,12 and 12 on a LAMA/LABA combination inhaler13 to prevent an exacerbation over a 12-month period.

The review found that patients taking mucolytics had fewer days of disability, for example days when they could do their normal activities more easily, compared to those given placebo.

They were also approximately one-third less likely to be admitted to hospital, although this result is based on only five studies.

The review also found that there was an overall improvement in quality of life, however, the mean difference did not reach the minimal clinically important difference of -4 units. There was a small improvement in lung function and no increase in side effects in those patients taking a mucolytic compared with placebo.

CHOICE OF MUCOLYTIC

Mucolytic therapy can be suitable for patients at any stage if they have a chronic cough, productive of sputum, typically seen in chronic bronchitis.1,3

Prior to March 2020 most patients with COPD were seen at least annually for a review of their COPD.

Due to patients with COPD being asked to ‘shield’ and GP practices being advised to only see patients face-to-face if essential to do so for clinical reasons, many practices reduced face-to-face consultations during the pandemic and introduced remote consultations using online, phone and video-links.

However, a remote consultation can be an opportunity to discuss non-pharmacological interventions too. Patients should be asked about their fluid intake. In healthy individuals even mild dehydration can slow cognitive decision making, increase fatigue, impair memory, alertness and concentration, and very importantly, physical performance.14 In people with chronic bronchitis this can further exacerbate problems with sputum clearance. The patient should be reminded to drink at least 1.2 litres of fluid a day to reduce the risk of dehydration.15

Every patient should be asked if they are able to clear their chest effectively or if they are struggling with sputum clearance. They should be reminded of the importance of keeping physically active, to help with sputum clearance, and reminded about the active cycle of breathing techniques (ACBT), which have been found to improve sputum production and cough efficiency in patients with COPD.16 If the patient continues to struggle to expectorate their sputum, a referral to a respiratory physiotherapist may be of benefit. Some patients are suitable for positive expiratory pressure (PEP) devices. In PEP therapy the patient exhales against a fixed-orifice resistor. This generates a pressure during expiration ranging from 10-20 cm H2O. This can then help promote effective airway clearance by mobilising secretions.17

For those patients who, despite being well hydrated and trying to keep physically active and coughing effectively, continue to struggle to expectorate sputum, a mucolytic drug may be trialled.

In the UK there are currently two mucolytics licensed for long-term use in people with COPD. These are carbocisteine and NAC.2 A third drug, erdosteine, is also available, but is only licensed for short-term use in acute exacerbations of chronic bronchitis.

Carbocisteine

Carbocisteine is a mucolytic agent that has been shown to affect the nature and amount of mucus glycoprotein that is secreted in the respiratory tract, and studies have shown that carbocisteine reduces goblet cell hyperplasia.18

Dosage

- The dosage of carbocisteine is initially 2250 mg daily, prescribed as 375 mg capsules, two capsules three times daily

- This is reduced to 1500 mg daily, given as two capsules twice daily or one capsule four times daily when a satisfactory response is obtained.19

Carbocisteine is not associated with interactions with other drugs, but it is contraindicated in patients with active peptic ulceration.19

There are concerns about how often the dose of carbocisteine is reviewed: around 45% of patients remain on the initiation dose, and are not down-titrated.20 When the dose is reduced, additional consultations are needed to check whether the lower dose remains effective.

The size of the carbocisteine capsules is also large and it can prove difficult for some patients to swallow them. It is thought that up to 60% of people over the age of 60 years have struggled to take solid medicines, such as capsules, at some time.21 This can be caused by having a dry mouth, breathlessness or dysphagia.22 Although carbocisteine also comes in liquid, granules and syrup preparations, these preparations are much more expensive than the capsules.

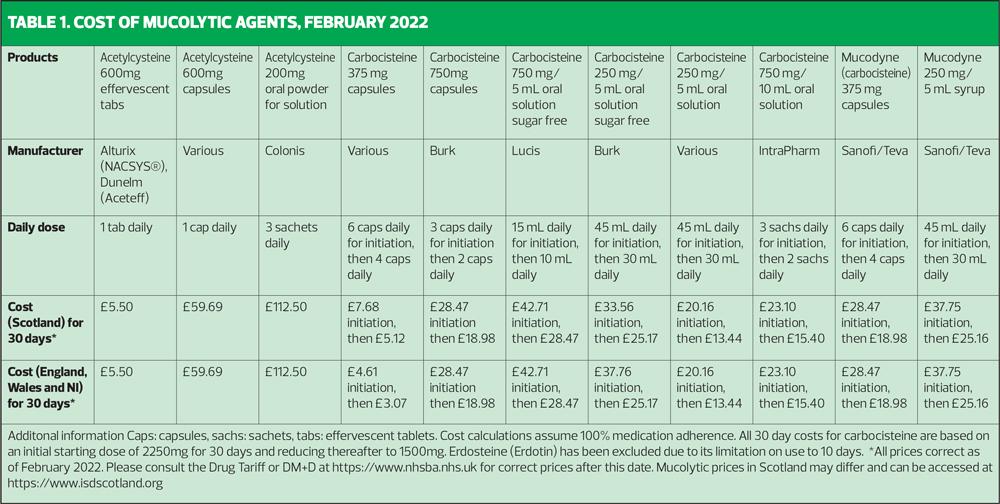

The price of carbocisteine is regulated by the Drug Tariff (See Table 1).

N-acetylcisteine (NAC)

NAC is a mucolytic and antioxidant drug that may also influence several inflammatory pathways by working on oxidative stress, an important trait in the pathogenesis of COPD.23

It comes as a 600mg effervescent tablet which is taken once daily. Patients with a reduced cough reflex are advised to take the tablet in the morning. There is no need for downward titration as the dose is fixed at 600 mg daily.24

Interactions

- NAC may enhance the vasodilatory effects of nitroglycerin

- Activated charcoal can decrease the effects of NAC

- If the patient requires concomitant oral antibiotics, they should be taken 2 hours before or after NAC to avoid a risk of inactivation of the antibiotic

- NAC should not be given concomitantly with cough medicines.24

Contraindications

Like carbocisteine, caution is advised in patients with a history of peptic ulceration, especially when used concomitantly with other medicines known to irritate the mucous membrane of the gastrointestinal tract.

NAC is a once-daily drug. A systematic review comparing once daily to twice and three times daily dosing regimens in chronic disease management found that in 20 studies examined, all reported higher adherence rates in patients using less frequently dosed medications, between 2% and 44% improvement in once versus twice daily dosing and 22-41% in thrice daily dosing.25

Erdosteine

Erdosteine is a mucolytic licensed for symptomatic treatment of an acute exacerbation of chronic bronchitis. It is a short-term use drug and should only be prescribed at 300mg capsules twice daily for up to 10 days. It is not licensed for patients who routinely struggle to expectorate their sputum where carbocisteine or NAC would be the mucolytic of choice.26

- It is commonly associated with epigastric pain and altered taste.

- It is contraindicated in people with liver or renal failure, those with active peptic ulceration, and in those with hypersensitivity to any components of the medicine.26

- It is more expensive than either carbocisteine or NAC.

CASE STUDIES

David

David attends for his annual COPD review:

- He is a 60-year-old accountant who was diagnosed with COPD 5 years ago

- He is an ex-smoker with a 24-pack-year history

- He has no occupational exposure to any other noxious fumes or gases

- He lives alone.

His current symptoms include a productive cough and breathlessness on exertion. His breathlessness is getting progressively worse, causing him to limit his activities. He is expectorating thick, sticky sputum, which he is finding it increasingly difficult to clear. He is also embarrassed about coughing when at work or when he goes out as he feels people are staring at him, especially since the COVID-19 pandemic, as he feels people may think he has coronavirus.

He has had two clinician confirmed exacerbations of COPD in the last year, requiring a course of both antibiotics and oral corticosteroids.

Initial assessment

David scored 3 on his mMRC dyspnoea score and 14 on his CAT score, indicating a high symptom burden. He was already on a dry powder triple therapy inhaler, containing an inhaled corticosteroid and 2 long-acting bronchodilators. He had picked up 11 prescriptions for this inhaler in the past 12 months, indicating good adherence. He also had a dry-powder salbutamol inhaler on his repeat prescription list, of which he had picked up 10 units in the past 12 months.

His inhaler technique was good with both devices.

He was drinking approximately 4 large glasses of water each day as well as several cups of tea and caffeinated coffee, especially whilst at work.

As he remained symptomatic, he was prescribed a trial of NAC, (Nacsys® 600mg). As he was working, the once daily dosing of NAC compared to the twice or four times daily dosing of carbocisteine fitted better with his lifestyle. David was advised about potential side effects associated with NAC. He had no other contraindications in his medical history indicating that NAC would not be an appropriate drug for him to trial.

Non-pharmacological advice is equally as important as pharmacological advice and David was also given advice on increasing his activity levels by having a short walk during his lunch break and switching to decaffeinated coffee, as caffeine can have a diuretic effect, increasing the risk of dehydration.26

One-month review

David had a telephone consultation 4 weeks after commencing NAC. While the dose of NAC does not have to be titrated, it is important to review the efficacy and tolerability of any new medicine. His mMRC dyspnoea score had decreased to 2, and his CAT score to 8, indicating a reduction in symptom burden.

David reported that he had followed the advice given to him at his annual review and had increased his fluid intake and was gradually increasing the distance he was walking each day. He had not had any side effects from the Nacsys®. He said he was finding it easier to expectorate his sputum now and was less socially embarrassed.

He had not had any further exacerbations of his COPD.

Following this consultation, the NAC was added to his repeat prescription list. He was advised on the importance of maintaining the non-pharmacological advice given and to report them if he experienced any adverse events.

Marjorie

Marjorie was seen at home for her annual COPD review.

- Marjorie, aged 82 years, was widowed 5 years ago and is now struggling to live independently in her bungalow

- She is an ex-smoker, and has a 46-year pack history

- She finds any activity makes her breathless, and is relying on her family to do her shopping and housework

- She has a productive cough every day, and struggles to expectorate her sputum

- She finds the cough exhausting and struggles to eat at times because of her breathlessness and cough

- She feels very fatigued, especially in the afternoon and evening

- She has severe COPD, with an FEV1 of 31% of predicted

- She has had two hospital admissions in the last year with infective exacerbations of COPD

- She has several other long-term conditions including type 2 diabetes, ischaemic heart disease, osteoporosis, and stress incontinence, exacerbated by her cough

- She reports to struggling to swallow all her tablets and sometimes selects the ones she finds easier to swallow.

Marjorie scored 4 on her nMRC dyspnoea scale and 25 on the CAT test, indicating a very high symptom burden. Marjorie had been prescribed an ICS/LABA dry-powder inhaler (DPI), that was prescribed twice daily and a soft-mist LAMA inhaler that was to be used once daily. She had a salbutamol metered dose inhaler (MDI) that she used frequently.

She was also prescribed carbocisteine but had been continued on 2 capsules TDS for many months. She was also on 12 other tablets for her other long-term conditions.

Understandably she struggled to take all her various inhaled and oral medications as prescribed and often forgot to take some of them.

Seeing Marjorie at home proved to be very beneficial. Her inhaler technique was poor with the MDI but good with the DPI, and she did have enough inspiratory flow to use a DPI inhaler. She was shown how to use an alternative DPI device so that her inhaled medication could be switched to a triple therapy DPI that she only needed to use once daily. Her salbutamol was also switched to a DPI, enabling the same inspiratory effort to be used for both devices. Her carbocisteine was also switched to NAC so that she only had to remember to take it once daily rather than TDS. She was advised to take her inhaler and NAC first thing in the morning, when she was more alert and less tired.

As she was also struggling with her other oral therapies, she was referred to her local community pharmacist, who arranged a structured medicine review for Marjorie and she was subsequently provided with a Dosette box.

Marjorie was given advice on increasing her fluid intake. As stress incontinence had been a problem for Marjorie and was one of the reasons she was limiting her oral fluid intake, she was asked if she would like a referral to the local continence service for the provision of pads, which she accepted.

Marjorie was also struggling to remain independent at home, due to her breathlessness. She agreed to be referred to the local pulmonary rehabilitation group, which she was eventually able to commence between service suspensions due to Covid-19. In the interim she was referred to the community respiratory occupational therapist, who helped her with breathlessness management and assessed her for equipment which could be provided to help Marjorie maintain her independence.

Review

Marjorie was contacted after 4 weeks by telephone to see if she had experienced any side effects from either the NAC or the change in her inhaled therapies. She reported no side effects and felt that the new regimen was much easier for her to follow. She also reported that she felt her cough was less problematic and she had not needed to use her salbutamol so frequently. She had increased her fluid intake as advised and felt the input from the Occupational Therapist and Continence Adviser had been very beneficial. She now had more confidence to leave her house to visit family. The NAC and the triple therapy DPI were then added to her repeat prescription, as well as the DPI salbutamol.

She was seen at the outpatient clinic after 3 months, on a day she was attending the pulmonary rehabilitation course. She said that she was enjoying the course, mainly for its social aspect as she was now meeting other people with COPD and felt less socially isolated. She said on her previous pharmacological regimen she did not think she would have been able to attend, due to breathlessness, cough, and fatigue.

She had not had any exacerbations since the changes in both her non-pharmacological and pharmacological management.

TAKE HOME MESSAGES

- COPD is a common, chronic condition that can result in high morbidity and mortality

- Chronic bronchitis results in airway inflammation and increased mucus production which can lead to an increase in exacerbations of COPD

- Frequent exacerbations can result in a decline in health-related quality of life and higher risk of mortality

- COPD guidelines advocate the use of mucolytics for some patients, alongside bronchodilators and inhaled corticosteroids for people with chronic bronchitis who have a chronic cough, to reduce the risk of exacerbations

- When prescribing a mucolytic drug, patient lifestyle, pill burden and the ability to swallow medications should be taken into consideration, as well as cost-effective prescribing

- Whenever a change is made to a medication the patient should be offered a review to assess the effect of the drug and if any side effects have been noted. Only then should the drug be added to their repeat prescription list

- Non-pharmacological management strategies are equally important as COPD can affect people physically, psychologically, and socially

- We need to address all the patient’s needs so that they can take back control of their condition.

REFERENCES

1. NICE NG115. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in over 16s diagnosis and management guidance; https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng115

2. Scottish Government. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD): best practice guide; 2017 https://www.gov.scot/publications/copd-best-practice-guide

3. Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD). Global Strategy for the Diagnosis, Management and Prevention of COPD, 2021. https://goldcopd.org

4. Kim V, Criner G. The Chronic Bronchitis Phenotype in COPD: Features and Implications. Curr Opin Pulm Med 2015;21(2):133-141

5. Boka K, Emphysema. Medscape 2019. https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/298283-overview

6. Bustamante-Marin XM, Ostrowski LE. Cilia and Mucociliary Clearance. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 2017;9(4):a028241.

7. Camner P, Mossberg B, Philipson K. Tracheobronchial clearance and chronic obstructive lung disease. Scand J Respir Dis 1973;54:272–81

8. Bronchiectasis Toolbox: Airway Clearance in the Normal Lung. https://bronchiectasis.com.au/physiotherapy/principles-of-airway-clearance/airway-clearance-in-the-normal-lung.

9. Cystic Fibrosis Foundation. Reasearch into mucus. https://www.cff.org/research-mucus

10. Tilley A, Walters M, Shaykhiev R, et al. Cilia dysfunction in lung disease. Annu Rev Physiol 2015: 77:379-406

11. Poole P, Sathananthan K, Fortescue R. Mucolytic agents versus placebo for chronic bronchitis or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2019:5(5): CD001287

12. Suissa. S. Number needed to treat in COPD: exacerbations versus pneumonias. Thorax 2013;68(6):540-3

13. Treatment of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease: Guidelines from the American Thoracic Society. Am Fam Physician 2021;104(1):102-103.

14. Cheuvront SN, Kenefick RW. Dehydration: physiology, assessment, and performance effects. Compr Physiol 2014;4:257-85.

15. NHS Choices. Water, drinks and your health, 2018. https://www.nhs.uk/live-well/eat-well/water-drinks-nutrition/

16. Shen M, Li Y, Ding X, et al. Effect of active cycle of breathing techniques in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a systematic review of intervention. Eur J Phys Rehabil Med 2020 Oct;56(5):625-632.

17. Fagevik Olsen F, Lannefors L, Westerdahl E. Positive expiratory pressure. Common clinical applications and physiological effects. Respir Med 2015;105(3):297-307.

18. Bai C, Song Y. The function of mucins in the COPD airway. Curr Respir Care Rep 2013;2:155-166. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13665-013-0051-3

19. Carbocisteine 375mg Capsules. Summary of product characteristics. Last updated 23 October 2020. https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/product/3291/smpc

20. Hamilton AR, Murphy A. Carbocisteine: are we getting it right? Poster presented at the annual UKCPA Autumn Symposium, Leicester, 14 November 2015.

21. Strachan I, Greener M. Medication-related swallowing difficulties may be more common than we realise. Pharmacy in Practice 2005;15(9): 411-414

22. Wright D. Prescribing Medicines for Patients with Dysphagia. A handbook for healthcare professionals. Grosvenor House Publishing; 2011

23. Matera M, Calzetta L, Cazzola M. Oxidation pathway and exacerbations of COPD: the role of NAC. Expert Rev Respir Med 2016;10(1):89-97

24. Nacsys 600mg Effervescent Tablets. Summary of product characteristics. Last updated 09 February 2021. https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/product

25. Saini S, Schoenfeld P, Kaulbeck K, Dubinsky M. Effect of medication dosing frequency on adherence in chronic diseases. Am J Manag Care 2009;15(6):e22-33.

26. Erdotin 300mg capsules. Summary of product characteristics. Last updated 31 May 2019. https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/product

27. Alfaro T, et al. Chronic coffee consumption and respiratory disease: A systematic review. Clin Respir J 2018;12(3):1283-1294

Related articles

View all Articles