Guideline in a nutshell: Improving vaccination uptake

MANDY GALLOWAY

MANDY GALLOWAY

Editor

Practice Nurse 2022;52(5):12-15

With some exceptions, vaccine uptake rates have been falling and, in order to provide population-level protection, it is vital that everyone plays their part in encouraging their patients to accept the offer of vaccination

A new guideline from NICE aims to improve the uptake of vaccination in the general population in the light of declining vaccination rates and increasing numbers of cases of vaccine-preventable diseases.1

Vaccinations provide both personal and population-level protection against many diseases, and high uptake rates create population-level protection for both immunised and, in most cases, non-immunised people. Some people are unable to be vaccinated for medical reasons, some may not yet be eligible for vaccination – such as new-born babies, some may be at increased risk of disease – the elderly or those with compromised immune systems.2

Some vaccines, for diseases such as shingles, only protect those people who receive them.

But in all cases, it is vital that everyone who is eligible for vaccination should be encouraged to accept it.

Although uptake of the COVID-19 vaccination and boosters has been high [See flu article in this issue] and may have boosted confidence in vaccinations generally, in recent years, vaccine coverage has been declining. In 2017-18, vaccination uptake was lower for nine of the 12 routine vaccinations at ages 12 months, 24 months and 5 years in England. And although coverage for the first measles, mumps and rubella (MMR) vaccine dose increased, uptake for the second dose has declined – from 89.3% in 2015, to 87.8% in 2018.

As Practice Nurse reported in April, the latest data for July to September 2021 revealed uptake for the first dose of MMR at 24 months was 88.6% and for the second dose, it was 85.5%. Two doses are needed for optimum protection for the individual, and vaccine coverage needs to be at 95% to achieve herd immunity.

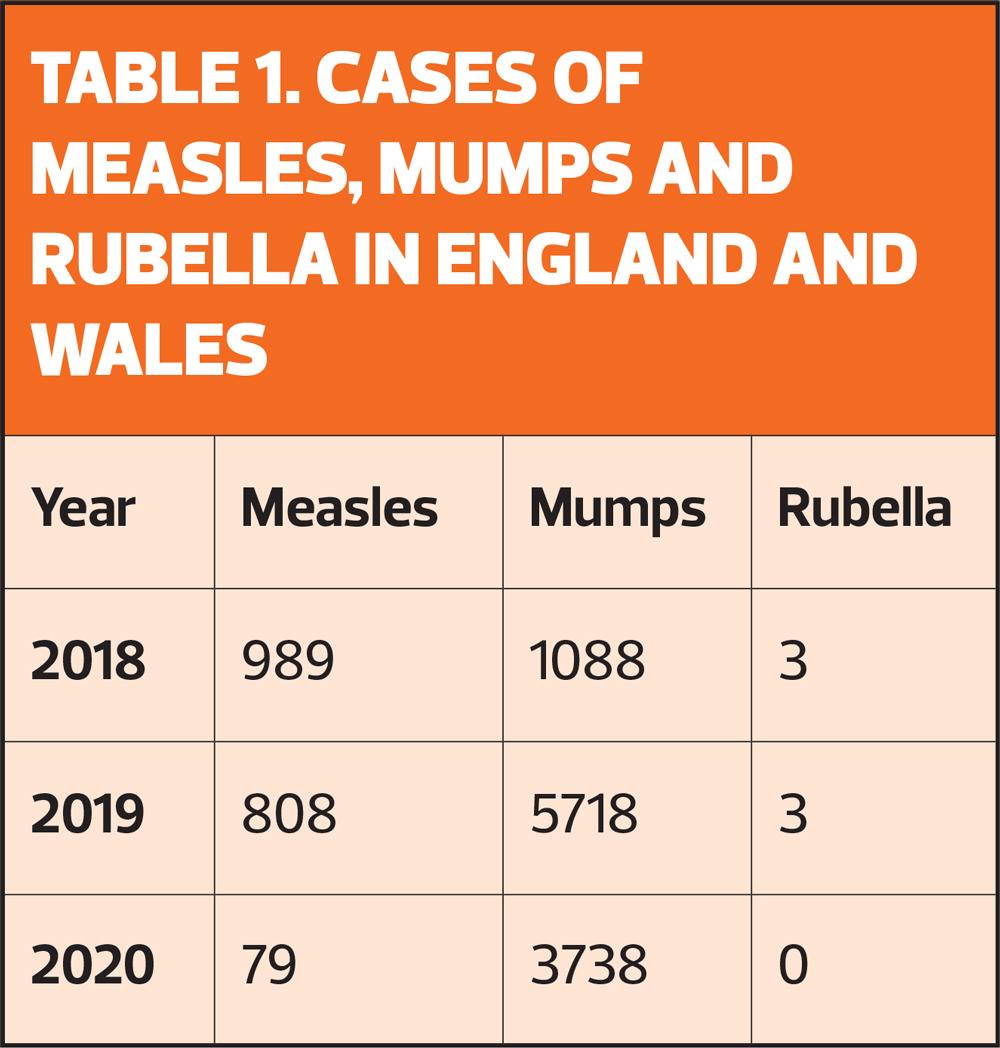

Between 2018 and 2020, there were 1,876 cases of measles in England and Wales (Table 1),3 and nine deaths, including six among adults.4

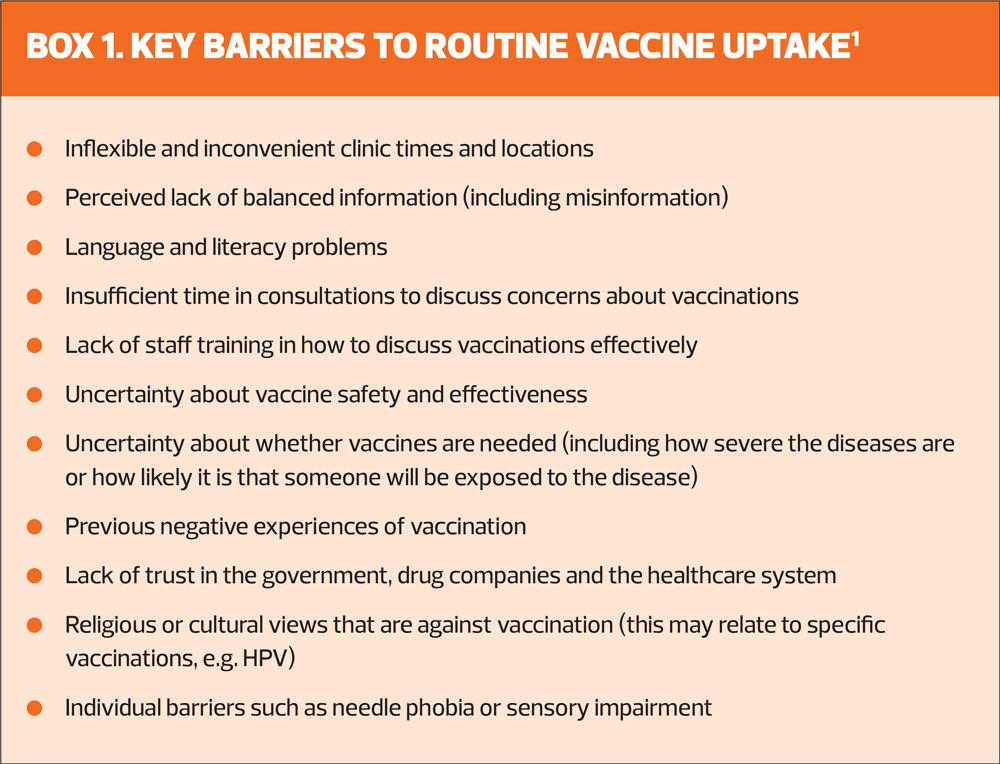

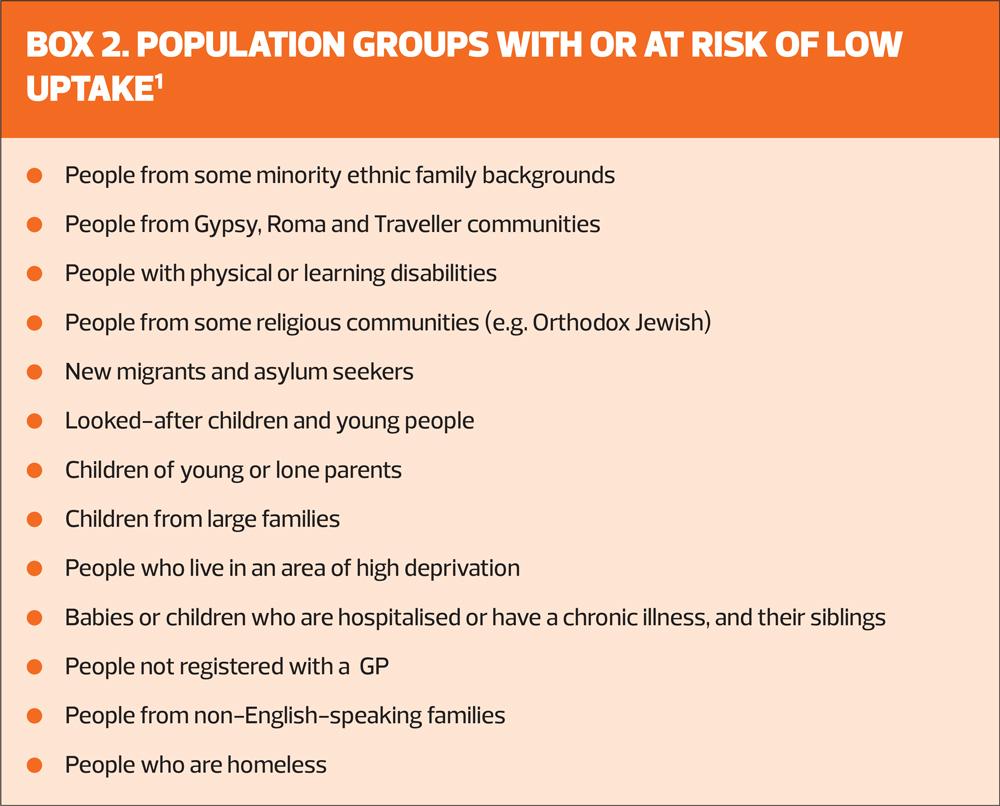

Reasons for low uptake include poor access to healthcare services, particularly among communities such as Gypsy, Roma and Travellers, refugees and asylum seekers who may not be registered with a GP. Furthermore, some migrants may not understand the UK health system and what is available to them.2

Another issue may be insufficient capacity within the NHS for providing vaccinations, although this is belied by the delivery of both the COVID-19 vaccination and booster programme, and last year’s record-breaking seasonal flu campaign.2

Yet another reason for low uptake is the continuing presence of inaccurate claims about the safety and effectiveness of vaccines, which can lead to ‘vaccine hesitancy’ and which the World Health Organization identifies as one of the top ten threats to global health.5

IMPROVING UPTAKE

A key recommendation to improve uptake is for each practice to have a named vaccination lead. Without one, vaccine-related tasks may not be prioritised, given the conflicting demands on practice staff time.

Having a named vaccination lead in each practice can help identify people who are housebound, and therefore less likely to be vaccinated because they cannot attend appointments, and ensure they are vaccinated. And while it may not be possible to vaccinate people in some non-healthcare settings, having a named individual can ensure that strategies are in place to make sure that these people are signposted to vaccination services.

Many GP practices already have a register of people who are housebound that the vaccination lead could use. In practices that do not have a register, the lead could identify people who decline vaccination because they cannot attend the surgery, and code them appropriately.

The vaccination lead would be responsible for ensuring:

- Vaccination records are validated and updated

- People who are eligible for vaccination are identified

- Invitations and reminders are sent to people who are eligible

- Vaccines are administered and recorded

- Coordination with other providers

- GP practices and child health information services (CHIS) understand each other’s reporting systems and processes

- Best practice is followed for ordering, storing, distributing and disposing of vaccines

Another important task for vaccination leads is to ensure that all staff who are in contact with people eligible for vaccination – even if they do not administer vaccines – have ongoing education about vaccination, so that they:

- Understand who is eligible for vaccination on the routine NHS schedule

- Are aware of the barriers to vaccination

- Understand the benefits and risks of vaccination

- Know where to signpost people for further information

It is particularly important that practitioners who administer vaccine are given the time, resources and support to:

- Undertake mandatory training before administering vaccines

- Include training on vaccination as part of CPD, including how to have effective and sensitive conversations about vaccination

- Ask people about any questions and concerns they may have about vaccination and to offer personalised responses (or direct them to relevant sources)

- Provide tailored information on the risks and benefits of vaccination

- Understand when a vaccine is contraindicated and when it can still be delivered

- Overcome individual barriers to vaccination e.g. learning disability, needle phobia, sensory impairment.

Education for practitioners involved in delivery vaccinations has been shown to increase uptake, and can help them feel confident when discussing vaccination.

Having effective conversations about vaccination can be particularly helpful when trying to address vaccine hesitancy. In addition, some people with allergies or specific conditions may think they are unable to have a vaccination because they think it is contraindicated, but this is often not the case. If the practitioner understands when a vaccine is contraindicated, and can discuss these concerns with the patient or carer, fewer people may be prevented from being vaccinated.

It is also important that vaccine-related education is available for non-clinical staff who are in contact with people who are eligible for vaccination: they need a basic knowledge of immunisation practices and issues so they are able to hold a simple conversation about the benefits of vaccination, and can point people in the right direction for further information. Education increases staff confidence, and helps to make every contact count to increase the opportunities for patients to be vaccinated.

OPPORTUNISTIC VACCINATIONS

NICE recommends using every available opportunity to identify people eligible for vaccination, including at registration, during health and developmental reviews as part of the healthy child programme, and whenever people make contact with healthcare professionals – including community pharmacists. Other opportunities present when people’s circumstances change – for example, when people move to care homes or when a child enrols at nursery or school.

Unless a person has a documented (or reliable verbal) vaccine history, GPNs should assume they are not immunised and plan a full course of immunisations: see UKHSA guidance on vaccination of individuals with uncertain or incomplete immunisation status, and refer to the Green Book, Chapter 11.6,7

Use prompts and reminders from electronic medical records to identify people who are eligible and due or overdue for vaccinations, and add prompts to the records of parents or carers if children’s vaccinations are overdue.

When people eligible for vaccination are identified opportunistically, GPNs should:

- If possible, discuss any outstanding vaccinations with them (or their family members or carers) and offer vaccination immediately

- Otherwise, encourage them to book an appointment to discuss the vaccinations or for vaccination

- Consider referring a child’s parents or carers to the health visitor or school nurse, as appropriate to the child’s age.

HOUSEKEEPING

Even if the vaccination is declined, the offer should be recorded in the person’s records. When administering a vaccine, ensure that the information is recorded accurately – this should include:

- Details of consent to the vaccination (including if someone else has consented on the person’s behalf, and their relationship to the person)

- The dose, batch number, expiry date, vaccine name and vaccine product name

- The date, route and site of administration

- Any reported adverse reactions

- Whether the vaccine was administered under Patient Specific Directions or Patient Group Directions.

Patient-held records should be updated at the time of vaccination, or if not available at the time, at the next healthcare appointment. Childhood vaccinations should be reported promptly to CHIS (and CHIS should notify GP practices of any vaccinations given outside the practice).

ESCALATING CONTACT

Patients who do not respond to invitations or attend clinics should be identified, and sent a reminder. They may not have given the practice up to date contact details, e.g. if they have moved house, so it is important to check that they have received the invitation and/or reminder. You may need to use another method of contact, such as a phone call or text message.

Contact the parents or carers of children aged 5 or under who have not responded to a reminder if a vaccination is approaching, within 2 weeks for immunisations for babies up age 1, and within 3 months for children aged 1 year and over. It is important that follow-up occurs rapidly, or parents/carers might think it was acceptable to defer vaccination, and this would expose the child to higher risk of contracting the diseases targeted by vaccination. The limits are shortest for babies because they have vaccinations due at 2, 3, and 4 months but reminders for older people are less time sensitive because they can be vaccinated for shingles or pneumonia over a period of several years.

When talking to a child’s parents or carers who have not responded to an invitation or reminder, explore their reasons for not responding, and try to address any issues they raise.

There is evidence to show that if someone does not respond after being sent a reminder, an escalating system of contact can be effective. This might initially involve a phone call from a GP receptionist, then a GPN, and finally from the GP, until the person is vaccinated or declines.

You can enlist the help of other health and social care practitioners – health visitors, social workers or key workers – while respecting the person’s decision if they refuse vaccination. If someone refuses vaccination, record the reason why, and make sure they know how to get a vaccination at a later date if they change their mind.

CONCLUSION

It is essential that everyone in primary care does everything possible to increase the uptake of vaccination to prevent outbreaks of vaccine-preventable diseases. Vaccination rates have been in decline in recent years – although it is to be hoped that the high uptake of COVID-19 vaccination may have a knock-on effect on other vaccinations – and while cases of measles, mumps and rubella were comparatively low last year, the UK saw significant outbreaks of both measles and mumps in 2018 and 2019. It is easy to forget that the diseases the UK’s vaccination programme is designed to control can be severe and have life-changing consequences. Be positive about vaccination, and knowledgeable. Be empathetic, not confrontational. At the end of the day, people have the right to refuse vaccination, no matter how unwise, but be sure to tell them the door is open if they change their minds.

REFERENCES

1. NICE NG218. Vaccine uptake in the general population; 17 May 2022. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng218

2. NICE NG218. Guideline scope: vaccine uptake in the general population. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng218/documents/final-scope

3. UKHSA. Confirmed cases of measles, mumps and rubella in England and Wales: 1996 to 2021; updated February 2022. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/measles-confirmed-cases/confirmed-cases-of-measles-mumps-and-rubella-in-england-and-wales-2012-to-2013

4. UKHSA. Measles notifications and deaths in England and Wales: 1940 to 2020; updated February 2022. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/measles-deaths-by-age-group-from-1980-to-2013-ons-data/measles-notifications-and-deaths-in-england-and-wales-1940-to-2013

5. World Health Organization. Ten threats to global health in 2019. https://www.who.int/news-room/spotlight/ten-threats-to-global-health-in-2019

6. UKHSA. Vaccination of individuals with uncertain or incomplete immunisation status. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/vaccination-of-individuals-with-uncertain-or-incomplete-immunisation-status

7. UKHSA. UK immunisation schedule: the green book, chapter 11. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/immunisation-schedule-the-green-book-chapter-11

Related guidelines

View all Guidelines