COVID-19, long term conditions and mental health

Katherine Ellerby

Katherine Ellerby

RGN, RM, BSc (Hons)

Non-medical independent prescriber, NDFSRH

Practice Nurse and Clinical Research Nurse

Practice Nurse 2021;51(1):22-27

The psychological impact of the global pandemic is undeniable, and coronavirus continues to have an impact on the mental and emotional wellbeing of people with long term conditions, as well as people recovering from COVID-19: what GPNs can do to offer support

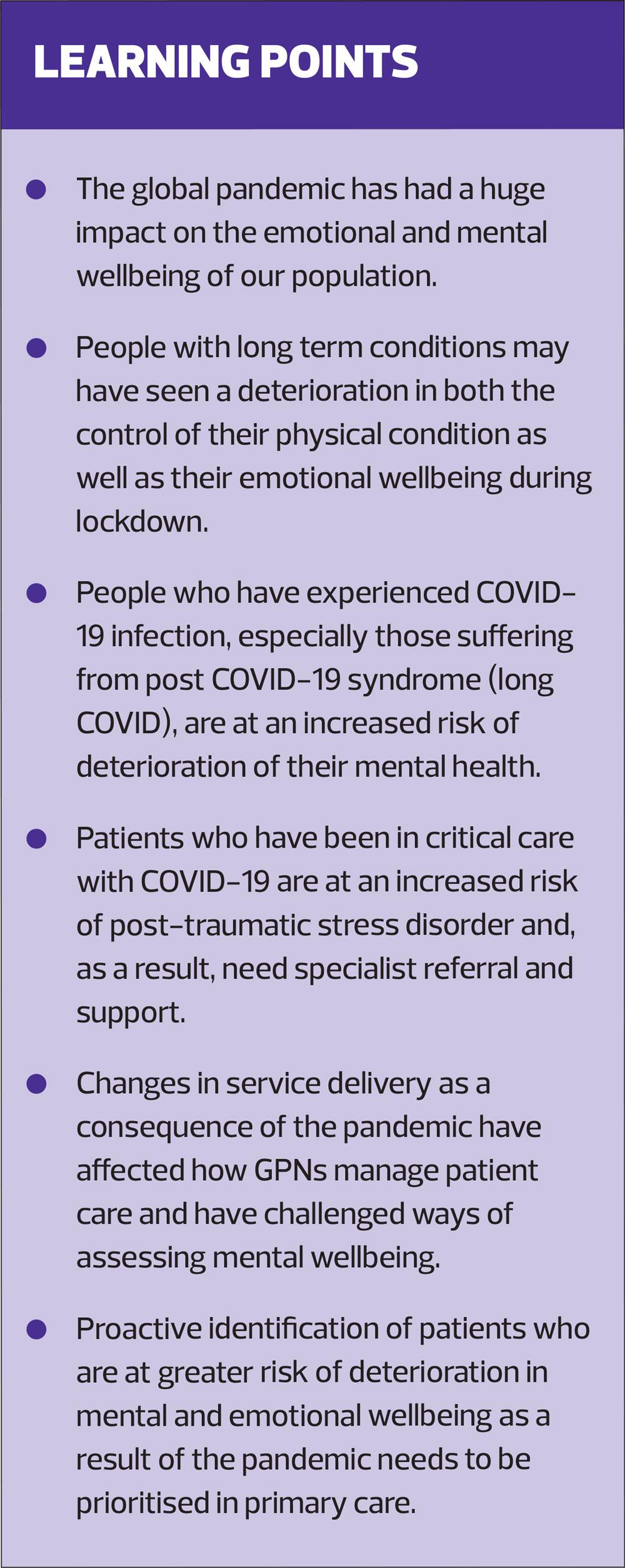

Fear. Loneliness. Powerlessness. The impact of COVID-19 on the mental health and wellbeing of our population, both nationally and globally, has been overwhelming and it’s not, by any estimation, over yet. The enormous change in our daily routines and behaviours, vital to reduce the number of COVID-related deaths, has cost us socially, personally and economically. Not only is there a fear of the wide-reaching physical manifestations of the virus itself, but also fear of its continuing impact on the lives we lead – social isolation, denial of physical contact, limitations to our freedom, the devastating impact from loss of employment and income. The hope of returning to some sort of ‘normal life’ is constantly slipping from our grasp as we endure further lockdowns.

PANDEMICS AND MENTAL HEALTH

In June 2020 the Economic and Research Council published a review of the evidence relating to the impact of social isolation in the context of a number of pandemics and other public health crises throughout the world.1 Unsurprisingly, the review demonstrated that detrimental impacts on mental health from social isolation during public health crises are more common in vulnerable and disadvantaged groups. Equally, those with greater social restrictions reported greater levels of anxiety, depression and, in some cases, post-traumatic stress disorder. Evidence from non-COVID epidemics around the world, namely SARS (Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome) and MERS (Middle East Respiratory Syndrome), suggests that the impact of isolation on mental health is not a short term problem.2

During the initial coronavirus outbreak in China, 70% of people reported psychological distress.3 In the UK, deterioration of mental wellbeing peaked at the height of the pandemic period during the initial lockdown and, while there may be signs of recovery in the population overall, evidence from the Public Health England COVID-19 Mental Health and Wellbeing Surveillance Report highlights that the mental health of the nation has not returned to pre-lockdown levels,4 nor is it likely to any time soon. What is abundantly clear is that the negative effect of this pandemic on many people’s mental health, especially those with greater health inequalities, is a long term issue.5,6

MENTAL WELLBEING

Simply put, social interaction is an essential part of what makes us human. Positive relationships, be it with family, friends or communities, have one of the biggest and most favourable impacts on our quality of life and mental wellbeing.7 Conversely, loss of social connections and an increase in loneliness and feelings of worthlessness – whether people have pre-existing mental health problems or not – are inevitably detrimental to our emotional wellbeing.1 Furthermore, as the virus has swept through our population, causing a rise in morbidity and mortality, it has left in its wake family members in grief, mourning and heartache. Many have been kept away from their loved ones at a time of greatest need, and ultimately for some, in their final hours. It is no wonder that the mental wellbeing of our nation has been severely challenged.

PEOPLE WITH LONG TERM CONDITIONS

We know that our patients with long term conditions (LTCs), especially those who have been shielding, have had even tighter restrictions on their daily lives than the rest of us.7 As well as the emotional impact of having to shield, for some people the knowledge that they are more susceptible to the virus and at greater risk of its potential fatal effects has heightened their fear and anxiety.8

LTCs are a significant burden of disease in the UK and, prior to coronavirus, LTCs have represented over 50% of appointments in primary care.9 At the height of the pandemic, four in ten patients were not seeking help from their GP for fear of adding to the burden on the NHS.10 High risk and poorly controlled patients were prioritised, which meant that routine reviews for the more well-controlled patients with respiratory conditions, diabetes and heart disease, for example, were being deferred or undertaken remotely, by telephone or video consultation. As a consequence, the Quality and Outcomes Framework for 2020/21 has been reviewed and amended to reflect the need to target the more vulnerable patients during the pandemic.11 For others control of their LTCs worsened, be it due to their change of lifestyle and/or ready access to health professionals.12

Even without COVID-19, we know that having a long term physical condition increases the risk of poorer mental health, such as low mood, depression and anxiety disorders.13 We also know that physical and mental health are inextricably linked – people with physical health conditions have a greater risk of mental ill-health and, equally, people with mental health conditions have an increased risk of physical co-morbidity. The cycle is self-perpetuating.

The latest figures from the Office for National Statistics demonstrate that 1 in 5 adults were experiencing low mood and depression during the pandemic, with increased anxiety in older adults and those with a debilitating LTC.14,15 The evidence shows that people with co-morbidities have significantly higher rates of morbidity from COVID-19, and those over 80 years of age are 70 times more likely to die compared to those under 40.16,17 Death rates are also higher in ethnic minority groups and in areas of deprivation, as well in those who are obese. Having an LTC also contributes to an increased risk of death. Given these facts, it is not surprising that mental wellbeing has been, and continues to be, significantly impacted by the COVID pandemic.17

TECHNOLOGY AND THE CHANGING FACE OF CONSULTATIONS

As we know, during the initial lockdown face to face LTC monitoring was quickly replaced by telephone or video consultations, with some variation between practices. By doing so, necessary though this might have been, we have had to ask patients who were less familiar with this type of consultation to make yet another adjustment to their lives.

You can argue that there are positives to take from this change of practice, for example, reducing time and effort for patients to attend in person, enabling self-monitoring in a more relaxed environment at home, and empowering patients to take more responsibility for their condition by doing so.18,19 However, for some patients it hasn’t been, and still isn’t, easy. Implementing new frameworks, pathways and technological advances may be the way forward, but for some people this approach may be uncomfortable at best, and even detrimental enough to cause a downward spiral in their mental wellbeing as they struggle to adapt to this new way of working – something we need to be mindful of.

MANAGING MENTAL HEALTH OF PATIENTS WITH LTCs

One of the benefits of face to face contact with patients is the ability to pick up on non-verbal signs from the minute they walk into our rooms. Their posture, their greeting, their eye-contact (or lack of it), the way the patient is dressed and their general demeanour. When conducting consultations virtually, we may have to probe that bit more, and be proactive when asking patients about their mental wellbeing:

- Are they sad or ‘empty’ for much of the time?

- Do they frequently get tearful?

- Are they more irritable and intolerant of other people?

- Have they lost interest in activities they previously enjoyed?

- Is decision-making difficult?

- Do they have any thoughts about harming themselves?

Completing assessment tools, such as the 7-item Generalised Anxiety Disorder scale (GAD-7) and/or the 9 item Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) for depression may be useful at this time to get an insight into how our patients are feeling.20,21 However, there is a risk that the responses to such tools may be misrepresented by poor physical health rather than an accurate measurement of anxiety and depression.21

What we do need to do is help our patients to recognise when they are struggling emotionally, give them the confidence to self-manage their mental wellbeing and seek further help as necessary. We particularly need to hone in on and identify those with LTCs who are at a greater risk of mental health problems, especially, and including, those individuals who:21,22

- Are living alone

- Have worsening conditions

- Have been shielding

- Have been bereaved during the pandemic

- Have been more isolated from other people

- Have had their support network reduced

- Have become carers as a result of the pandemic.

POST-COVID RECOVERY

Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) following any life-threatening intensive care admission is well documented.23,24 Typically, patients who have been in critical care can experience a number of symptoms including:

- Irritability

- Fear of recurrent illness

- Hallucinations

- Flashbacks

- Insomnia

- Nightmares

- Avoidance of thoughts

- Heightened anxiety

- Negative thoughts or mood

- Forgetfulness and ‘brain-fog’.

While one in five adults who have been in critical care experience PTSD following discharge, for some people the psychological impact can persist for many months, sometimes years. COVID-19 is likely to be no exception. Following the 2005-06 SARS outbreak in Hong Kong, evidence suggests that 47.8% of people with SARS experienced PTSD with over a quarter of those suffering for up to 30 months after their initial recovery.2

COVID-19 restrictions can mean that visits from loved ones are prohibited. Critical care staff, out of necessity, are unrecognisable in their head to toe PPE, further dehumanising the situation. Furthermore, some individuals may experience the additional burden of ‘survivor’s guilt’ which they may struggle to resolve:

- ‘Why did I live when others didn’t?’

- ‘Have I infected my family or friends?’

- ‘Am I responsible for other people’s deaths?’

Clearly management of such intense emotional trauma needs specialist support through psychological therapies such as cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) and Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing (EMDR).24 However, GPNs need to ensure that they understand their role and responsibilities in identifying patients who have been through this traumatic event and who are now back in the community, supporting patients who have experienced trauma, and knowing the associated referral pathways.

Death of a loved one is enormously difficult at any time and losing a family member as a result of COVID-19 brings additional difficulties and challenges.25 The impact on mental health of bereavement during a pandemic is largely uncharted territory. GPNs may be well placed to offer initial support and advice for patients struggling with such a loss, and direct them to specialist support services.

LONG COVID

Current evidence suggests that 10-20% of people who suffered from milder forms of coronavirus infection are likely to have persistent symptoms beyond 8 weeks.26 Symptoms include persistent fatigue, cognitive ‘blunting’ (brain fog), memory issues, anxiety and depression as well as physical manifestations with respiratory, cardiovascular, inflammatory and gastrointestinal symptoms.26 Current estimates suggest that there could be as many as 60,000 people in the UK affected by ‘Post COVID-19 syndrome’ or ‘Long COVID’ for more than 3 months.27

The mental health impact on people who have recovered from COVID-19 is evident whether or not they had pre-existing mental health issues.28 The RCGP guidance document, ‘General Practice in the Post-Covid World’ recognises the need to enhance mental health support in primary care and encourages clinicians to actively identify patients who are in greater need of mental health support.28

In response to the Long COVID phenomenon NHS England is rolling out specialist clinics to provide holistic care of the physical, cognitive and psychological impact of COVID-19. This includes an assessment of mental health and wellbeing including depression, anxiety and post-traumatic stress disorder. NICE and SIGN, along with the RCGP have published much awaited guidance on post COVID syndrome.29

SUPPORTING MENTAL HEALTH DURING THE PANDEMIC

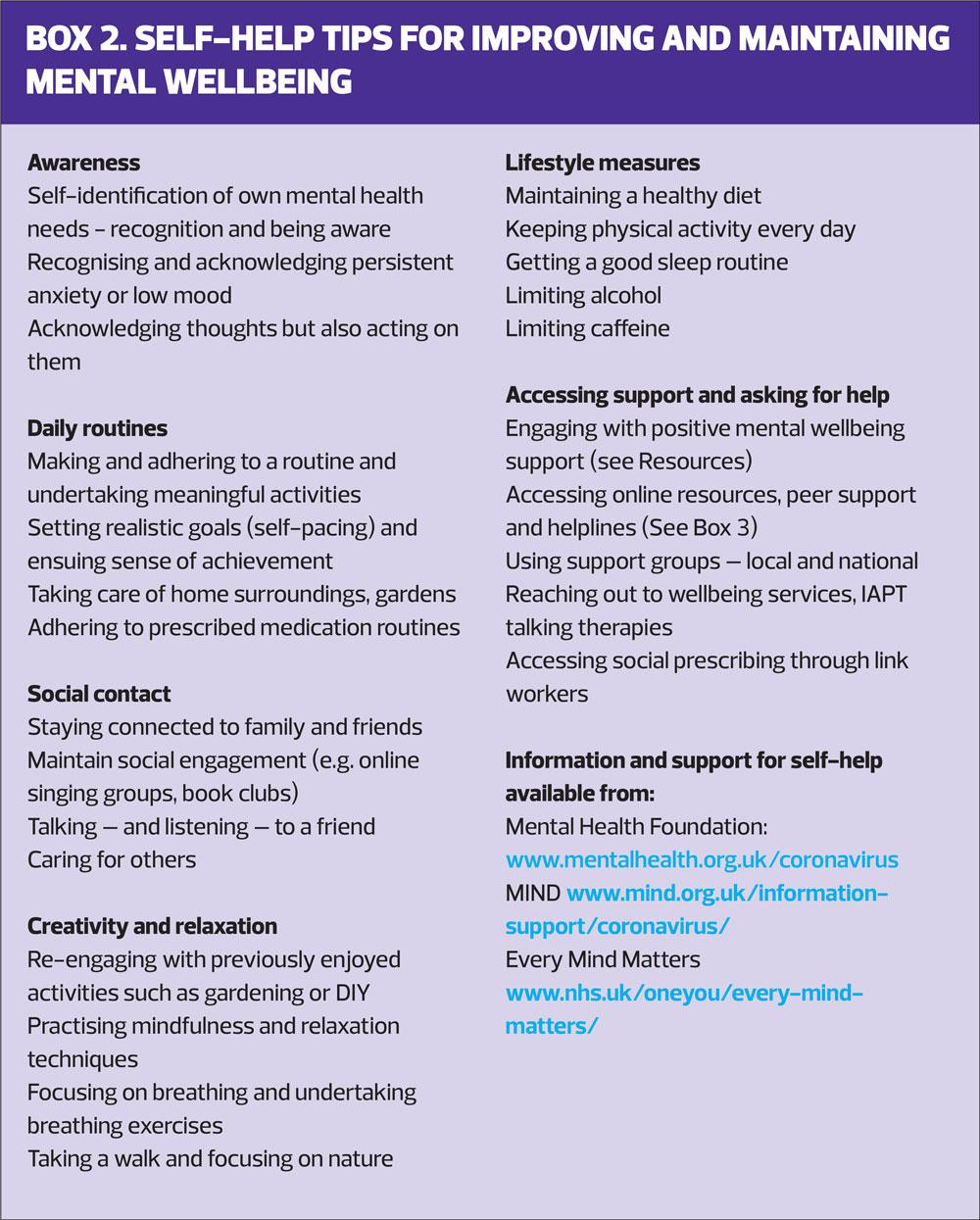

Acknowledging the impact of the pandemic on emotional and mental wellbeing is an important first step. Helping people to seek ways to maintain and improve both their physical and mental health is a delicate balance. We need to enable our patients to recognise when self-management isn’t enough and to seek further support from external agencies.

For some people the constant barrage of COVID-19 related broadcasts and information can create a huge escalation in anxiety. Social media does not always provide the best quality information. It may help to advise patients to limit and manage the amount of time they spend on social media in order to reduce information overload. Being able to acknowledge and accept that so much about the pandemic is way beyond personal control is a difficult, but important, step in reducing anxiety.

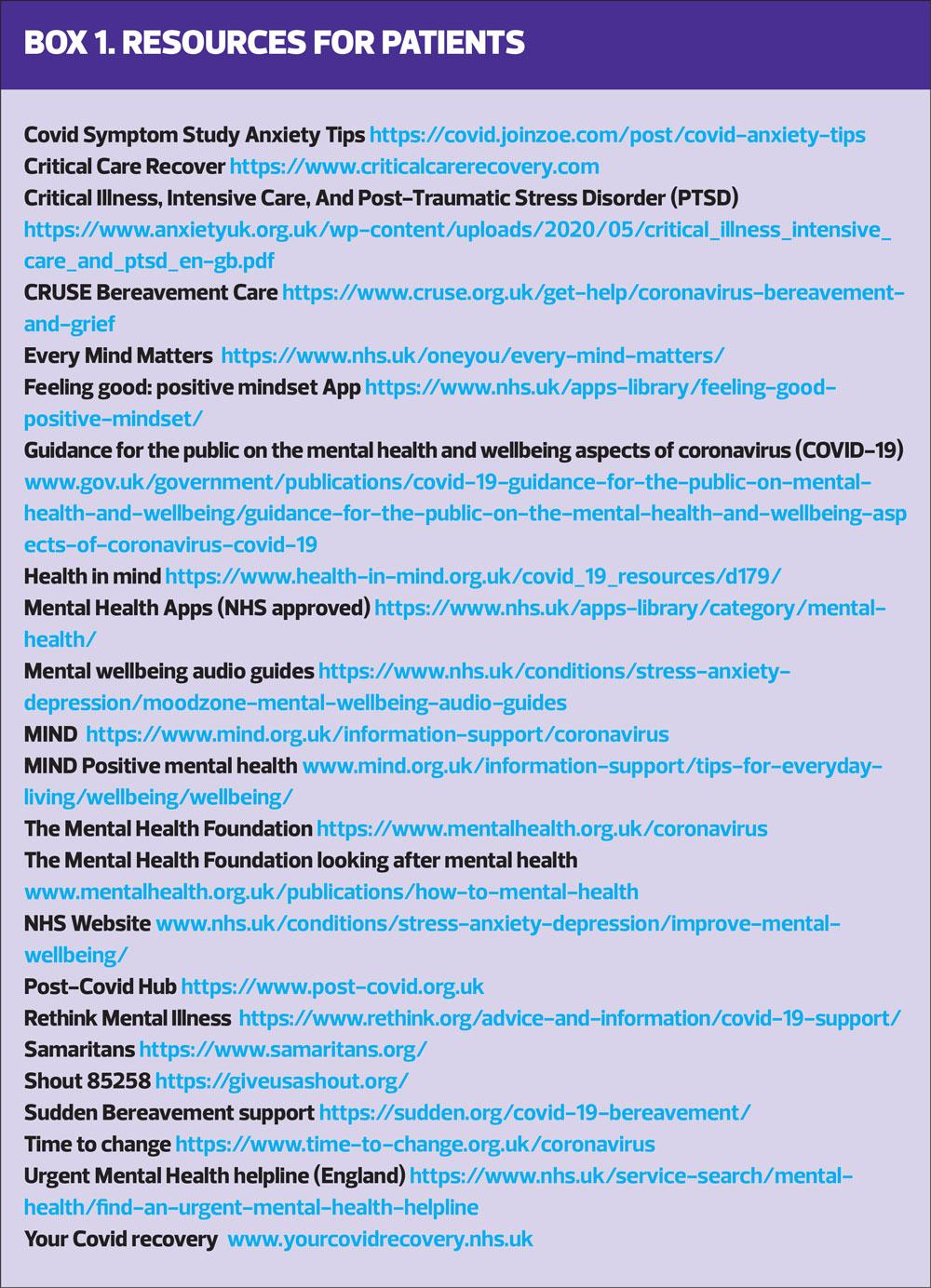

There are a number of excellent resources to support mental wellbeing, specifically in light of the effects of COVID-19, that we can signpost our patients to. The NHS website, ‘Your COVID Recovery’ as well as national organisations such as MIND, The Mental Health Foundation and Rethink Mental Illness are just some of the resources which have specific advice and support for people suffering as a result of the pandemic (See Boxes 1 & 2).

People who have pre-existing mental health problems are at greater risk of feeling particularly challenged at this time and we need to ensure our patients are able to access support from their mental health teams. 24-hour helplines, such as SHOUT 85258 and The Samaritans, are able to offer support. MIND and OCD UK have tips and advice for people who are struggling with obsessive compulsive behaviour from fear of the infection. For people with LTCs, specific support can be also accessed via national organisations and charities such as Diabetes UK, Asthma UK and The British Heart Foundation. GPNs can be proactive in signposting patients to appropriate resources and highlighting what is available for them.

ACTS OF KINDNESS

It is particularly fitting, even poignant, that the theme for this year’s Mental Health Awareness week, back in May this year, was ‘kindness’. Doing something good for someone else benefits our own emotional health and mental wellbeing. Paying attention to someone else and brightening their day can create a positive focus, rather than concentrating on all the things that are difficult and denied during the pandemic. Both The Mental Health Foundation and Health in Mind, amongst others, promote the concept that positive acts of kindness and doing something for someone else, however small, can make a big difference to the both the recipient’s and giver’s wellbeing.30,31

Acts of kindness may be as simple as complementing another person, or leaving a handwritten note to say thank you. Sometimes it is the smallest of gestures that have the biggest impact. Clearly this isn’t a new idea but, while the pandemic has wreaked fear, anxiety and loneliness in the population, we have also seen people, communities and neighbourhoods who have reached out, supported each other and reminded us that there is a lot of good in the world.

SUMMARY

We are still very much in the throes of this pandemic and restrictions continue. This time around the nights are longer and the days shorter, darker and colder. The impact on the mental health of our more susceptible patients is evident and we need to go the extra mile to check in on their wellbeing within the restrictions that we have. So often the case in primary care, we may need to seek out those patients who don’t necessarily seek out our help themselves. Maybe because control of their LTC isn’t as bad as others, maybe they are the people who ‘don’t like to make a fuss’, maybe they are just feeling too low to even ask for help or maybe they have recovered from COVID-19 and feel they have troubled the NHS enough.

We don’t know how long this is going to last or how long people’s lives are going to be restricted, but we can play our part in supporting our patients to get through this, and the impact it is having on their mental health, as best we can.

REFERENCES

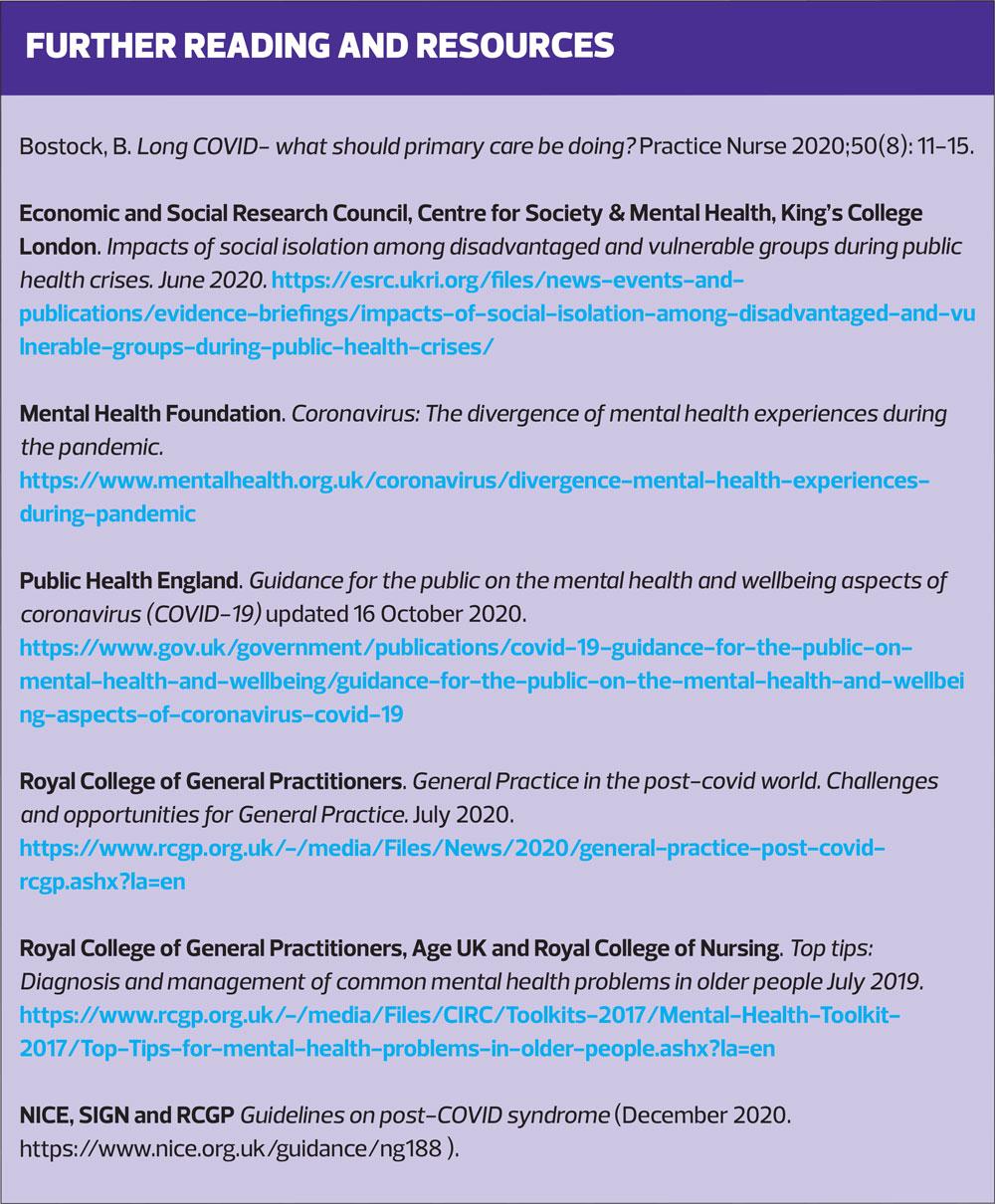

1. Economic and Social Research Council, Centre for Society & Mental Health, King’s College London. Impacts of social isolation among disadvantaged and vulnerable groups during public health crises. June 2020. https://esrc.ukri.org/files/news-events-and-publications/evidence-briefings/impacts-of-social-isolation-among-disadvantaged-and-vulnerable-groups-during-public-health-crises/

2. Hyunsuk J, Hyeon W Y, Yeong-Jun S, et al. Mental health status of people isolated due to Middle East Respiratory Syndrome. Epidemiol Health 2016;38:22016048 https://www.e-epih.org/journal/view.php?doi=10.4178/epih.e2016048

3. Fangyan T, Hongzia L, Shuicheng T, et al. Psychological symptoms of ordinary Chinese citizens based on SCL-90 during the level I emergency response to COVID-19. Psychiatry Research 2020;288:112992 https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0165178120306879?via%3Dihub

4. Public Health England. COVID-19 mental health and wellbeing surveillance report. Research and Analysis: Important findings so far. 8 September 2020. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/covid-19-mental-health-and-wellbeing-surveillance-report/2-important-findings-so-far

5. Kousoulis A, Van Bortel T, Hernandez P, et al. The long term mental health impact of covid-19 must not be ignored. Opinion. BMJ 5 May 2020. https://blogs.bmj.com/bmj/2020/05/05/the-long-term-mental-health-impact-of-covid-19-must-not-be-ignored/

6. Pierce M, Hope H, Ford T, et al. Mental health before and during the COVID-19 pandemic: a longitudinal probability sample survey of the UK population. The Lancet Psychiatry. 21 July 2020; 7(10); 883-892. https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lanpsy/article/PIIS2215-0366(20)30308-4/fulltext

7. The Mental Health Foundation. Relationships in the 21st Century. The forgotten foundation of mental health and wellbeing. Summary Report. 16 May 2016. https://www.mentalhealth.org.uk/sites/default/files/relationships-in-21st-century-summary-may-2016.pdf

8. GOV.UK Guidance on shielding and protecting people who are clinically extremely vulnerable from COVID-19. Updated 28 October 2020. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/guidance-on-shielding-and-protecting-extremely-vulnerable-persons-from-covid-19/

9. Department of Health and Social Care. Long Term Conditions Compendium of Information: Third Edition. May 2012. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/long-term-conditions-compendium-of-information-third-edition

10. Bostock N. Millions of patients 'avoiding calls to GP' during COVID-19 pandemic. GP Online. 25 April 2020. https://www.gponline.com/millions-patients-avoiding-calls-gp-during-covid-19-pandemic/article/1681384

11.NHS England and NHS Improvement. 2020/21 General Medical Services (GMS) Contract. Quality and Outcomes Framework (QOF) Guidance for GMS contract 2020/21 in England. https://www.england.nhs.uk/coronavirus/wp-content/uploads/sites/52/2020/03/C0713-202021-General-Medical-Services-GMS-contract-Quality-and-Outcomes-Framework-QOF-Guidance.pdf

12. Levine LS, Seidu S, Grenhalgh T, et al. Pandemic threatens primary care for long term conditions BMJ 2020;371:m3793 https://www.bmj.com/content/371/bmj.m3793

13. Health and Social Care Information Centre. Mental Health and Wellbeing in England Adult Psychiatric Morbidity Survey 2014. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/556596/apms-2014-full-rpt.pdf

14. Office for National Statistics. Coronavirus and depression in adults, Great Britain: June 2020. 18 August 2020. https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/wellbeing/articles/coronavirusanddepressioninadultsgreatbritain/june2020

15. Office for National Statistics. Coronavirus and anxiety, Great Britain: 3 April 2020 to 10 May 2020. 15 June 2020 https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/wellbeing/articles/coronavirusandanxietygreatbritain/3april2020to10may2020#personal-characteristics-associated-with-high-anxiety

16. The Kings Fund. Deaths from Covid-19 (coronavirus): how are they counted and what do they show?19 August 2020. Available at: https://www.kingsfund.org.uk/publications/deaths-covid-19

17. Public Health England. Disparities in the risk and outcomes of COVID-19. August 2020. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/908434/Disparities_in_the_risk_and_outcomes_of_COVID_August_2020_update.pdf

18.Collins B. Technology and innovation for long-term health conditions. August 2020. Available at: https://www.kingsfund.org.uk/sites/default/files/2020-07/Technology%20and%20innovation%20for%20long-term%20health%20conditions%20August%202020.pdf

19. Greenhalgh T, Vijayaraghavan S, Wherton J, et al. Virtual online consultations: advantages and limitations (VOCAL) study. BMJ Open. 2016;6: e009388. Available at: https://bmjopen.bmj.com/content/bmjopen/6/1/e009388.full.pdf

20. NICE CG123. Common mental health problems: identification and pathways to care; 2011 (reviewed August 2018). https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg123

21. Greenhalgh T, Knight M. A’court C, et al. Management of post-acute covid-19 in primary care. BMJ 2020;370:m3026 https://www.bmj.com/content/370/bmj.m3026

22. Mental Health Foundation. Coronavirus: The divergence of mental health experiences during the pandemic.

https://www.mentalhealth.org.uk/coronavirus/divergence-mental-health-experiences-during-pandemic

23. Khan Burki T. Post-traumatic stress in the intensive care unit. The Lancet Respiratory Medicine. 2019:7(10);843-844. https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lanres/article/PIIS2213-2600(19)30203-6/fulltext

24. NICE NG116. Post-traumatic stress disorder; 2018. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng116

25. Yardley S, Ralph M. Death and dying during the pandemic. BMJ 2020;369:1472. https://www.bmj.com/content/369/bmj.m1472

26. Public Health England. COVID-19: long-term health effects. 7 September 2020. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/covid-19-long-term-health-effects/covid-19-long-term-health-effects

27. NHS News. NHS to offer ‘long covid’ sufferers help at specialist centres. 7 October 2020. https://www.england.nhs.uk/2020/10/nhs-to-offer-long-covid-help/

28. Royal College of General Practitioners. General Practice in the post-covid world. Challenges and opportunities for General Practice. July 2020. https://www.rcgp.org.uk/-/media/Files/News/2020/general-practice-post-covid-rcgp.ashx?la=en

29. NICE, SIGN, RCGP. NG188. COVID-19 rapid guideline: managing the long-term effects of COVID-19; December 2020. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng188

30. The Mental Health Foundation. Random acts of kindness during the coronavirus outbreak. 11 September 2020. https://www.mentalhealth.org.uk/coronavirus/random-acts-kindness-during-coronavirus-outbreak

31. Health in Mind. Random acts of kindness during covid-19. https://www.health-in-mind.org.uk/covid_19_resources/i2281/random_acts_of_kindness_during_covid_19.aspx

Related articles

View all Articles