Sleep apnoea: assessment and management

Dr Gerry Morrow

Dr Gerry Morrow

MB ChB, MRCGP, Dip CBT

Medical Director Clarity Informatics and Editor Clinical Knowledge Summaries

Practice Nurse 2020;50(9):30-34

Sleep apnoea is almost certainly under recognised and under diagnosed in primary care. This article outlines the background, common features and the role of the practice nurse in assessment and management of the condition

Sleep apnoea, as a result of the upper airway collapsing, causes irregular breathing during sleep.1 This collapse of the airways can be partial (hypopnoea) or complete (apnoea), and leads to a transient arousal from deep sleep to wakefulness or a lighter sleep phase. This arousal allows restoration of normal airway muscular tone. The person then falls into a deeper sleep leading to the cycle repeating itself. These cycles can occur many times throughout the night. Fragmentation of the normal sleep pattern develops as a result, leading to reduced sleep quality, excessive daytime sleepiness, and reduced concentration and alertness.1

TERMINOLOGY

Obstructive Sleep Apnoea/Hypopnoea Syndrome (OSAHS) is the term used to describe the coexistence of excessive daytime sleepiness with irregular breathing at night.2

Another term, Obstructive Sleep Apnoea/Hypopnoea (OSAH), is used to describe people with irregular breathing at night, but without daytime sleepiness. OSAH is more common than OSAHS but is less likely to be seen in primary care.

The British Thoracic Society (BTS) use the term 'Obstructive Sleep Apnoea Syndrome' (OSAS) in people with repetitive apnoeas and symptoms of sleep fragmentation with excessive daytime sleepiness.3

INCIDENCE AND RISK FACTORS

OSAS affects all age groups. People frequently attend to see practice nurses with fatigue and other symptoms that could point to a diagnosis of OSAS. The reported evidence suggests that, in the UK, up to 4% of middle-aged men and 2% of middle-aged women are affected.4 International studies suggest that the prevalence of OSAS in children is around 1–2%, and this may be increasing with the increasing incidence of obesity. The incidence in children with congenital conditions (e.g. Down's syndrome, neuromuscular disease, and craniofacial abnormalities) is higher.5

In adults there are a number of known risk factors for developing OSAS and males are two- to three- times more likely to develop it than females. Other risk factors in adults include:

- Obesity

- Neck circumference greater than 43 cm

- Family history of OSAS

- Smoking

- Alcohol intake before bed

- Sleeping supine

- Hypothyroidism

- Craniofacial abnormalities

- Acromegaly.

Risk factors for OSAS in children include:

- Adenotonsillar enlargement

- Obesity

- Congenital conditions, such as Down's syndrome, neuromuscular disease, craniofacial abnormalities, achondroplasia, and Prader–Willi syndrome.2,4,5

COMPLICATIONS

The sleep disruption that occurs in OSAS can lead to several consequences.

Complications in adults

In adults, OSAS can lead to hypertension and some authors propose that OSAS has an independent role in the pathogenesis of hypertension.6

Five studies (n = 8,435) from a systematic review and meta-analysis concluded that OSAS increases the risk of stroke independently of other cardiovascular risk factors.7

People with untreated OSAS are at a 7-12 times greater risk of road traffic accidents compared with people without OSAS.8

Complications in children

Growth hormone is secreted during sleep and faltering growth rates are seen in severe cases of OSAS in children.5 Disturbed sleep can also lead to behavioural problems, irritability, poor concentration and poor school performance.

PROGNOSIS

In adults treatment with Continuous Positive Airway Pressure (CPAP) reduces both daytime and nocturnal blood pressure.9 A meta-analysis of 28 studies found a weighted mean difference in daytime systolic pressure of –2.58 mmHg and diastolic blood pressure of –2.01 mmHg. Similar results were found with nocturnal readings.10

A meta-analysis of children with sleep apnoea has shown a reduction in apnoea severity and improvement in quality of life after adenotonsillectomy.5

HISTORY AND EXAMINATION

History in adults

OSAS should be suspected in a person with any of the following, common symptoms:

- Excessive daytime sleepiness and snoring and/or impaired concentration

- Feeling unrefreshed on waking

- Mood swings, personality changes, or depression

- Nocturia.

Rarely, OSAS is also associated with nocturnal sweating, reduced libido, and gastro–oesophageal reflux disease (GORD). Any report from a bed partner of episodes of apnoea or choking noises while sleeping needs to be taken seriously.

If you suspect OSAS you should ask about any associated symptoms which may suggest an underlying head or neck cancer, such as unilateral nasal bleeding and/or severe nasal obstruction. Voice changes and/or unexplained hoarseness, or dysphagia are also symptoms that should raise suspicion. Since OSAS is most often associated with marked weight gain suspicion of a head or neck cancer should be raised if the patient reports an usually rapid onset of symptoms in the absence of significant weight gain.

You should ask about any risk factors for OSAS, listed above, and about the effects of daytime sleepiness on driving, work performance, relationships, mood, sleeping and social life. You should also consider taking a collateral history from a bed partner, if possible, regarding snoring habits, apnoeas and choking episodes.

History in children

Suspect OSAS in children with any of the following nocturnal symptoms:

- Snoring and pauses in breathing, which may be followed by a gasp or snort

- Restlessness and sudden arousals from sleep

- Laboured breathing

- Unusual sleep posture (for example head bent backwards)

- Bedwetting.

Daytime symptoms in children include changes in behaviour (e.g. irritability), poor concentration, decreased performance at school, tiredness and sleepiness. Failure to gain weight or grow and mouth-breathing should also raise suspicion.

Examination

OSAS is an upper airway problem so you will need to examine the upper airway. Look for enlarged tonsils, or a small jaw. The nose should also be examined for any blockage due, for example, to nasal polyps or a deviated nasal septum.

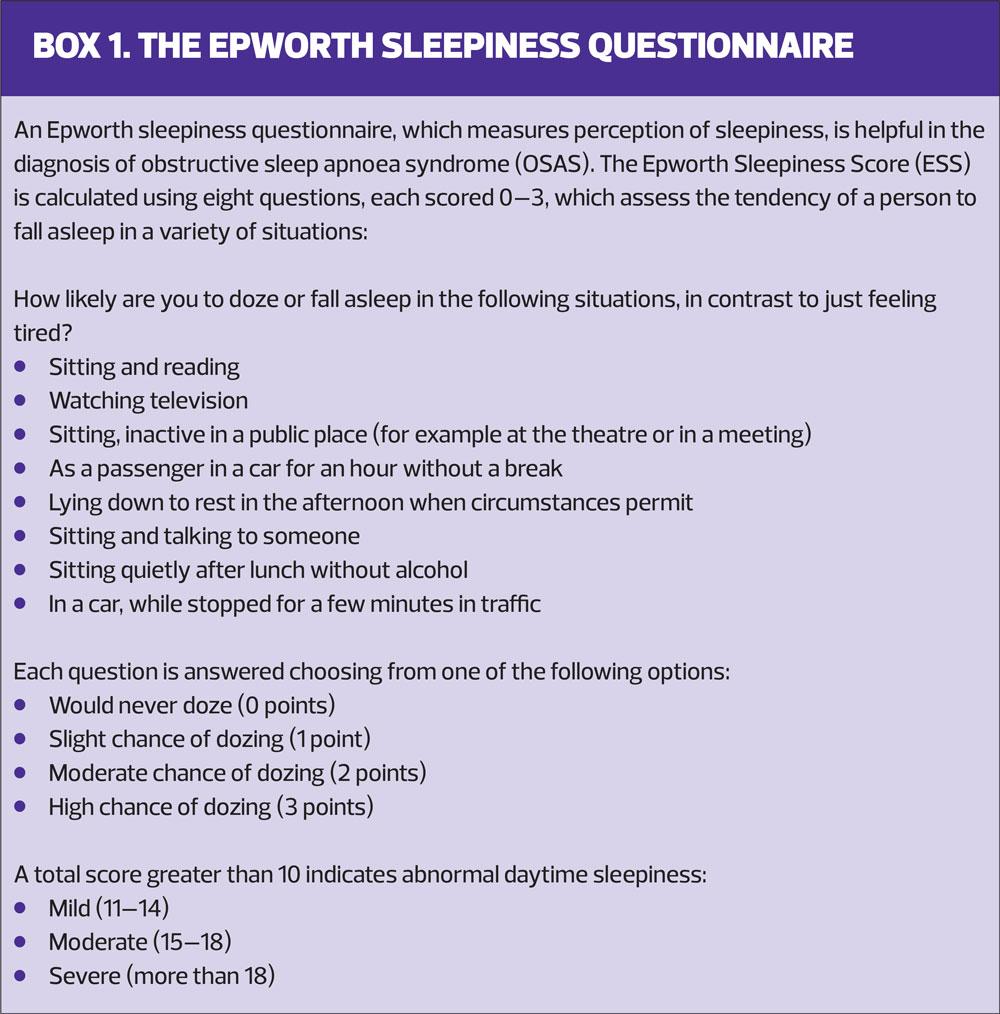

Check the person’s blood pressure, body mass index and neck circumference and ask them to complete an Epworth sleepiness questionnaire to assess the extent and severity of their symptoms (Box 1) You should also look for signs of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), respiratory failure or cor pulmonale as this will influence the urgency of referral. Consider arranging investigations if you suspect an underlying cause, e.g. thyroid function tests if hypothyroidism is suspected.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

There are many causes for daytime sleepiness, not all of which are sinister. The person may be experiencing sleep deprivation or a lack of sleep opportunity due, for example, to shift working or the advent of a new baby. Sleep may also be disturbed due to pain or anxiety, or restless leg syndrome. Depression may also cause daytime sleepiness. Some drugs, such as sedatives, beta blockers and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors can also cause sleepiness, so it is important to look at a person’s medication history. Neurological disorders, such as Parkinson’s or Motor Neurone Disease, or a previous head injury can also cause daytime sleepiness, as can hypothyroidism and narcolepsy.

Nocturnal choking or gasping may be caused by GORD, nocturnal asthma or heart failure. Panic attacks and night terrors may also cause a person to wake gasping.

REFERRAL

Urgent referral (2-week wait) of a person with suspected OSAS to an ear, nose and throat (ENT) specialist is essential if there are features suggestive of a head and neck cancer.

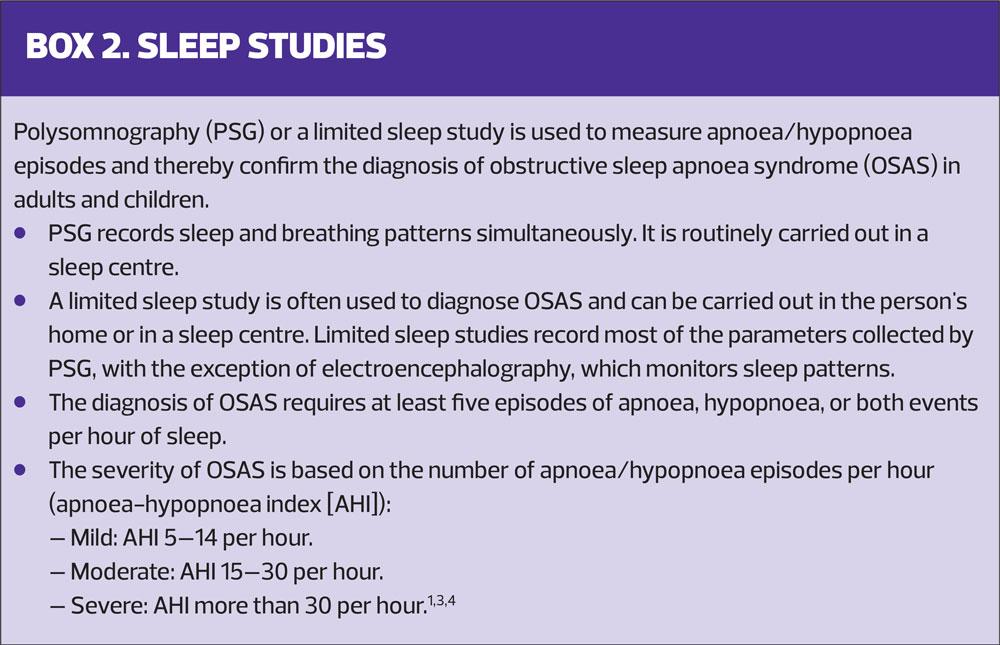

Referral to a sleep centre for sleep studies, (Box 2) is needed for confirmation of a diagnosis of OSAS, and for secondary care treatments, e.g. CPAP. However, sleep services have been severely disrupted during the pandemic, and there are likely to be delays in securing an appointment while centres deal with the backlog.10

Adults who need urgent referral include those who are sleepy while driving or working with machinery, or who are employed in hazardous occupations, for example, pilots or bus or lorry drivers. Such individuals must be advised not to drive until they have been assessed by a specialist.

Urgent referral to a sleep centre for confirmation of diagnosis is also necessary for adults who:

- Have signs of respiratory failure or heart failure

- Have symptoms suggestive of severe OSAS and comorbid COPD

Routine referral is indicated for adults who have symptoms suggestive of OSAS and/or an accompanying Epworth sleepiness questionnaire score of more than 10. However, when there are concerns about the person’s job security, personal communication with the sleep centre should be undertaken to ensure that diagnosis and treatment can be completed within four weeks of referral.

Children will need to be referred to a paediatric ENT specialist if they have features of adenotonsillar hypertrophy, symptoms of persistent snoring and features of OSAS.

SECONDARY CARE TREATMENTS

For adults, secondary care treatments for OSAS include the use of CPAP or intraoral devices.

CPAP is the first-line treatment for moderate or severe OSAS. It should only be used in mild OSAS if a person has symptoms that affect quality of life (inability to carry out daily activities) and when lifestyle advice or other treatments have failed or are inappropriate.4 Treatment with CPAP for OSAS has demonstrated significant reductions in both systolic and diastolic blood pressure,11 and people prescribed CPAP will require lifelong treatment and will have to wear either a nasal or face mask for airflow delivery at night. Poor adherence is common and may be due to a poorly fitting mask, problems with nasal dryness, nasal bleeding, or throat irritation.

Intraoral devices, such as a mandibular advancement device, can improve both sleep quality and nocturnal respiratory function in people with OSAS. They are appropriate for people who snore or have mild OSAS with normal daytime alertness. They are effective, non–invasive, and easy to manufacture.12 Intraoral devices can also be used as an alternative for people unable to tolerate CPAP.2

For children with clinical evidence of adenotonsillar enlargement, adenotonsillectomy may be offered.5 CPAP may be considered if adenotonsillectomy is contraindicated or not likely to be beneficial.5

THE ROLE OF THE PRACTICE NURSE

OSAS is almost certainly underdiagnosed in primary care so it is important that you are aware of the features that suggest it and refer appropriately. Once the diagnosis is confirmed there are a number of interventions that you can make that will be beneficial.

Lifestyle advice, where appropriate, can be immensely beneficial. Patients can be advised and supported to lose weight and exercise. They can be advised to reduce their alcohol intake and sedative use, where appropriate, and they should be advised and supported to stop smoking. In addition, if they habitually sleep supine they can be advised to try sleeping on their side.

OSAS increases the risk of cardiovascular disease (CVD) and an individual’s risk of CVD and diabetes should be assessed. Their blood pressure should be monitored regularly, and they should be encouraged to adhere to treatment with CPAP or intraoral devices. That these treatments can help manage symptoms and reduce the risk of long-term complications needs to explained and reinforced.

Patients may also benefit from information about support groups that provide self-management advice such as The Sleep Apnoea Trust Association.

ADVICE ABOUT DRIVING

Driving and entitlement to drive can be a particular concern and it is important to be aware of the issues so that you are able to advise patients appropriately. The BTS gives extensive advice regarding driving for people with OSAS.3

All patients must be advised to check with their insurer that they are still insured under their current policy.

People who are being investigated for, or have a diagnosis of sleep apnoea, but do not experience symptoms of daytime sleepiness of a severity likely to impair driving do not need to stop driving or inform the Driver and Vehicle Licensing Agency (DVLA). However, they should inform the DVLA, (but not cease driving) if they are successfully using CPAP or an intraoral device. As long as they are compliant with treatment, and their symptoms are controlled so that they no longer impair driving, their licence should not be affected.

The person has a legal requirement to inform the DVLA and stop driving if they are diagnosed with OSAS and their symptoms include sufficient sleepiness to impair driving. If, prior to formal diagnosis, the individual reports sufficient levels of sleepiness to impair driving there is a reasonable chance that this is due to a medical condition and they should stop driving pending diagnosis.

This guidance is applicable to both Group 1 (cars, mopeds, and motorbikes) and Group 2 (lorries and buses) drivers. In addition, for Group 2 drivers, compliance with treatment and ongoing symptom control must be assessed on a regular, usually annual, basis by the sleep specialist.

SUMMARY

OSAS is a common presentation in primary care. It is remediable and treatable, and treatment not only improves symptoms and lives but also reduces morbidity and mortality.

As practice nurses you will encounter people every day who have OSAS or risk factors for the condition. You will be ideally placed to assess, monitor, review and support people with OSAS as a core element of your role.

REFERENCES

1. NICE CKS. Obstructive sleep apnoea; 2015. https://cks.nice.org.uk/obstructive-sleep-apnoea-syndrome

2. SIGN. Management of obstructive sleep apnoea/hypopnoea syndrome in adults: a national clinical guideline. Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network. 2003

3. British Thoracic Society. Position statement. Driving and Obstructive Sleep Apnoea (OSA). 2019. https://www.brit-thoracic.org.uk/quality-improvement/clinical-resources/sleep/

4. NICE TA139. Continuous positive airway pressure for the treatment of obstructive sleep apnoea/hypopnoea syndrome. NICE technology appraisal 139.2008. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ta139

5. Powell S, Kubba H, O'Brien C, et al. Paediatric obstructive sleep apnoea (clinical review). BMJ 2010;340:c1918. doi: https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.c1918

6. Parati G, Lombardi C, Hedner J, et al. Recommendations for the management of patients with obstructive sleep apnoea and hypertension. Eur Respir J 2013;41(3):523-538.

7. Loke Y, Brown J, Kwok C, et al. Association of obstructive sleep apnea with risk of serious cardiovascular events: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2012;5(5):720-728.

8. Pagel JF. Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) in primary care: evidence-based practice. J Am Board Fam Med 2007;20(4):392-398.

9. Greenstone M, Hack M. Obstructive sleep apnoea (clinical review). BMJ 2014;348:3745 doi: 10.1136/bmj.g3745.

10. Association for Respiratory Technology & Physiology/British Thoracic Society. Sleep services during endemic COVID-19. May 2020. https://www.sleepsociety.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/Sleep_Services_During_Endemic_COVID-19_Version_1.3.pdf

11. Montesi S, Edwards B, Malhotra A, et al. The effect of continuous positive airway pressure treatment on blood pressure: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Clin Sleep Med 2012;8(5):587-596.

12. Lee CH, Mo J-H, Choi I-J, et al. The mandibular advancement device and patient selection in the treatment of obstructive sleep apnea. Archives of Otolaryngology Head and Neck Surgery 2009;135(5):439-444 doi:10.1001/archotol.125.10.1117

Related articles

View all Articles