Mucolytics in general practice

One of the treatments available for patients with COPD is mucolytic therapy, which reduces accumulation of mucus in the lungs, helping to prevent exacerbations - but this option can be overlooked. Here we look at how mucolytics can be used more effectively

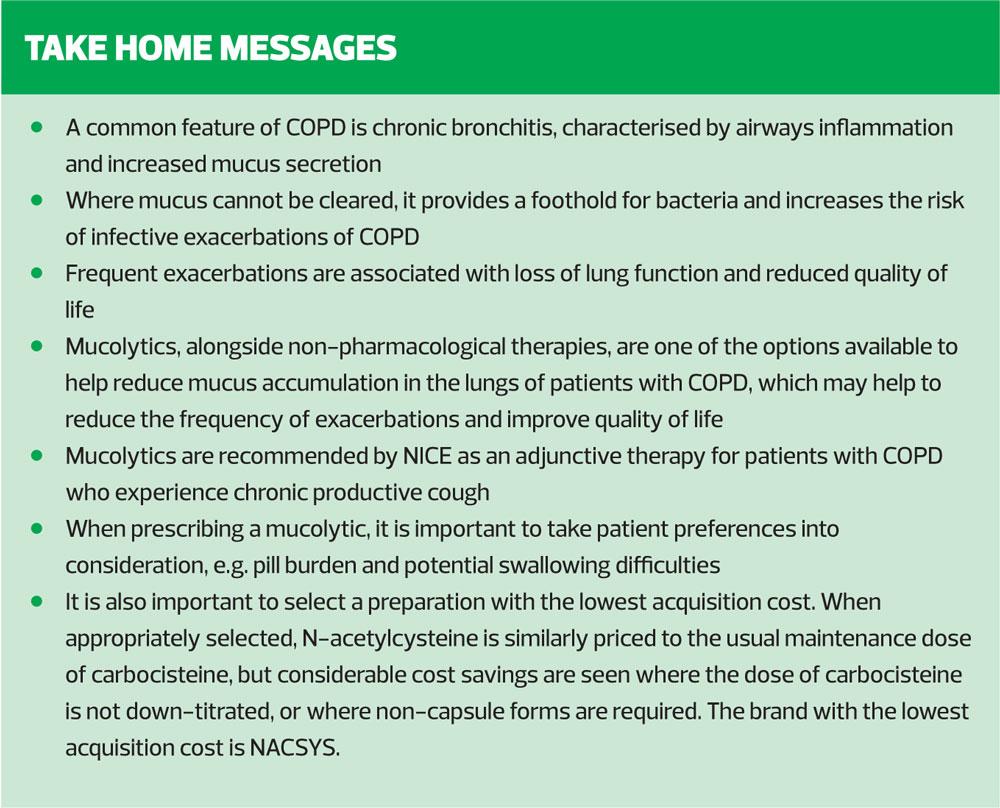

Prevention and treatment of exacerbations or flare ups are a key component in the management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD).1 Commonly caused by infections, either viral or bacterial, frequent exacerbations can result in reduced life expectancy, loss of lung function (measured as forced exhalation in one second [FEV1]) and an increase in breathlessness associated with deconditioning.1 One of the most common reasons for primary care practitioners to refer people with COPD to secondary care is acute exacerbation.

However, it is clearly most important to ensure lung function is preserved and quality of life promoted before most patients reach the stage of referral. Recently a surge of new inhaler therapies has highlighted benefits of inhaled therapy in improving symptom control and reducing exacerbations. Mucolytics, alongside non-pharmacological therapies, are one of the other options available to help reduce mucus accumulation in the lungs and thus prevent exacerbations and improve quality of life.2 However, at present they may sometimes be overlooked as a part of COPD care, perhaps due to lack of information on their efficacy and appropriate usage. The aim of this article is to clarify the dosing regime and various benefits and drawbacks of available therapies so that they can be more effectively used.

EFFECT OF MUCUS ACCUMULATION IN THE AIRWAYS

Mucus production in the airways occurs as part of the lung defence system against both inhaled particles and micro-organisms.1 Once these invaders of the respiratory tract are caught in the sticky mucus, the small hair like cells called cilia brush the mucus up and away from the airways.3 The cough mechanism then facilitates the removal of the mucus and trapped contents from the lungs.3

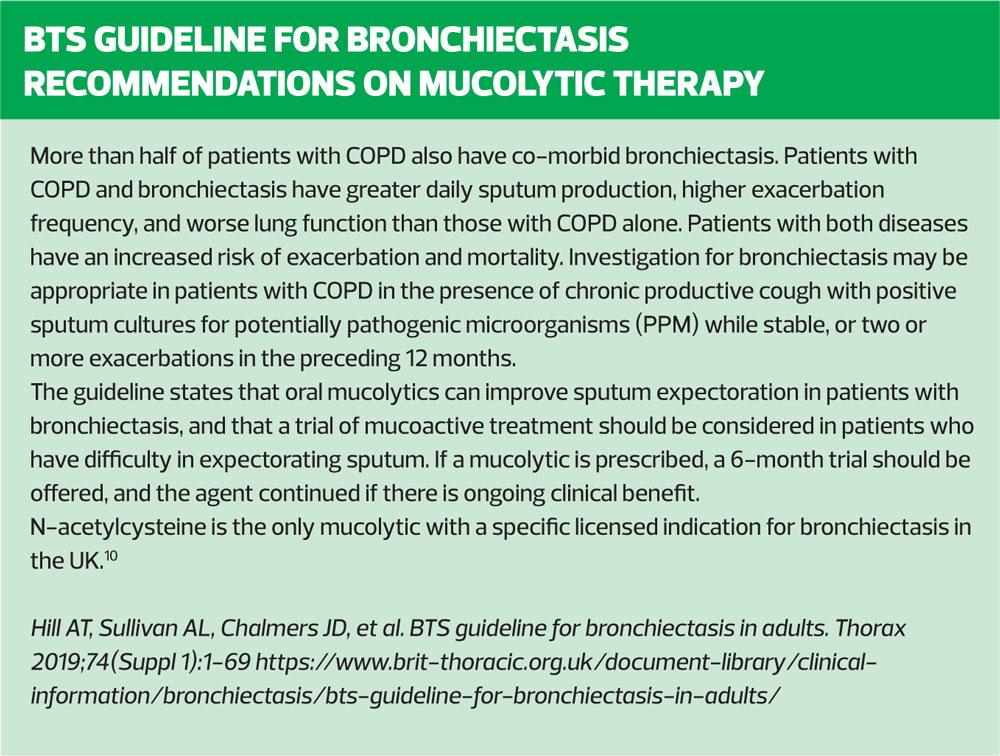

A common feature of COPD is chronic bronchitis, which is characterised by inflammation of the airways and increased mucus secretion.1 This increase in mucus can lead to difficulties in chest clearance without intervention.1 Where the mucus cannot be cleared it provides a foothold for bacteria and increases the chances of chest infection/infective exacerbation of COPD. High frequency of exacerbation is associated with loss of lung function and reduced quality of life.2 Repeated exacerbations can increase the level of deconditioning experienced by the person with COPD.

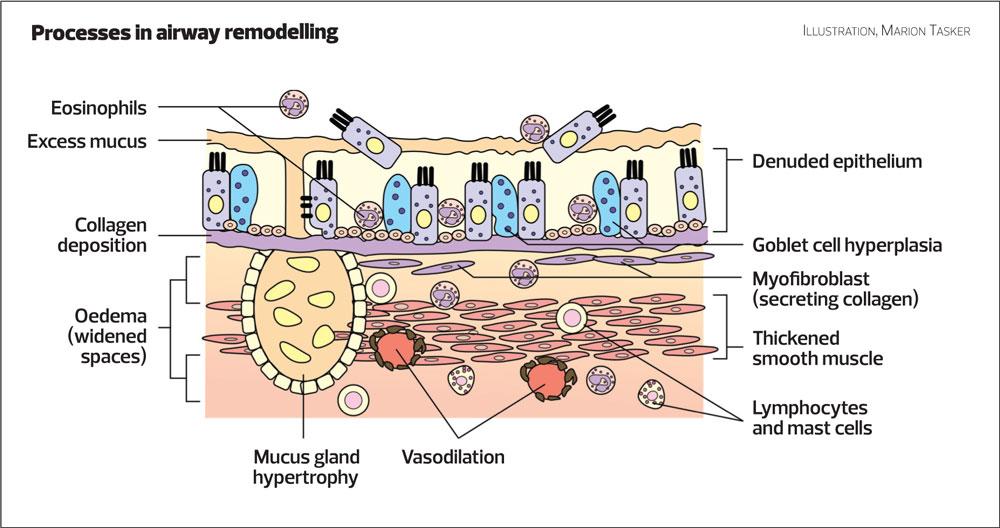

Another problem associated with chronic mucus accumulation and infection is remodelling of the airways. As the epithelium (thin surface layer) of the airways is damaged by invading microorganisms, the cells that are destroyed are replaced most frequently by more goblet cells, which are responsible for mucus production1 (Figure 1). This vicious and damaging cycle of cell destruction is then the cause of the increased frequency of infection. The result is that lung function deteriorates and the person with COPD becomes more symptomatic.

COUNTERING THE PROBLEM

Annual review provides an ideal opportunity to identify people with COPD who would potentially benefit from mucolytics. This is especially true as at annual review optimisation of other pharmacotherapy and non-pharmacological intervention is already a priority.4 The following should be considered:

Is the person smoking? Smoking cessation has been identified as a priority in COPD management and is a high value intervention.4,5 Studies have shown that irritants found in tobacco smoke interfere with mucus clearance and incidence of exacerbation is higher before smoking cessation than after.3

Is the person struggling with chest clearance? The COPD Assessment Test (CAT), a validated tool for the identification of symptom severity in COPD, can be helpful in identifying these patients as often they will score highly the symptoms of sputum and cough. It is not usual for a person with COPD to expectorate large volumes of mucus on a daily basis when well. Where this is the case alternative or co-existing diagnosis such as bronchiectasis should be considered.5

Has the person adequate levels of hydration? When a person is not adequately hydrated, mucus will be thicker and more difficult to expectorate. Therefore, simply reminding the person to aim to drink at least 1.2 litres of fluid per day to prevent dehydration,6 can have a profound effect.

Is the person active and able to cough effectively? Physical activity both helps to shake loose mucus in the airways, enabling it to be expectorated more readily, and encourages deeper breaths. This enables air to reach the smallest sections of the airways and get behind mucus allowing a more effective cough. The active cycle of breathing7 is a useful and effective chest clearance method and can be explained quickly and easily. Where chest clearance is a problem, referral to respiratory physiotherapy can be useful in teaching chest clearance methods and positive expiratory pressure devices may be employed to allow people to better clear their airways through the use of positive airways pressure and vibration.4,5

MUCOLYTICS

Where a person is active, hydrated and able to cough effectively, mucolytics are a pharmacological support that can help to make mucus less sticky and reduce the destruction of normal epithelium cells thus reducing the increase in goblet cells known as goblet cell hyperplasia.1 The NICE 2018 guideline for management of COPD recommends that practitioners consider mucolytics for people with chronic productive cough.4 Mucolytics are also recommended by the Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) in its most recent report, particularly for those who are not receiving an inhaled corticosteroid, based on evidence that they may reduce exacerbations and improve health status.5 NICE guidance does not recommend mucolytics routinely as a method of reducing risk of exacerbation. In practice this means it is important to think carefully about who will benefit from a trial of mucolytic therapy, and as per NICE guidance, ensure efficacy in the individual patient is reviewed before mucolytic therapy is continued.4

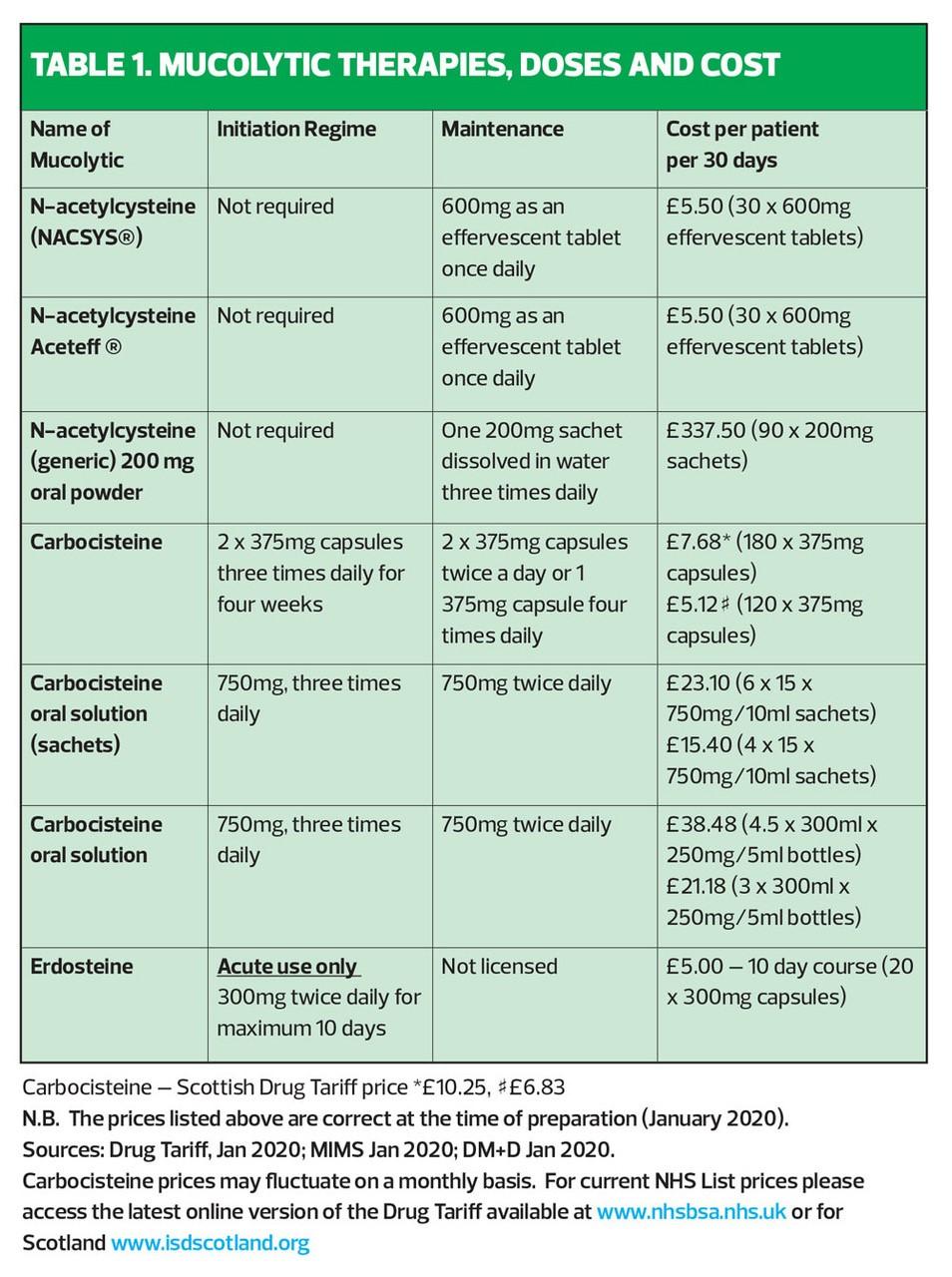

Where a person has chronic productive cough and is otherwise optimised in terms of treatment, carbocisteine and

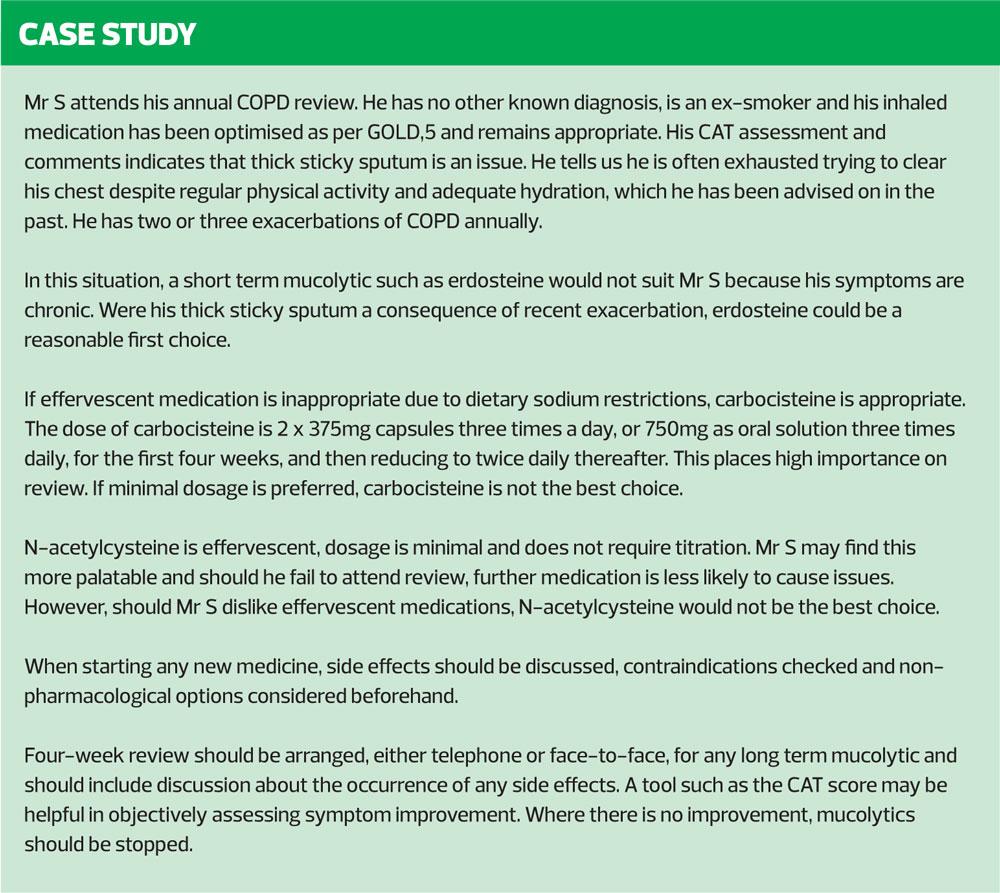

N-acetylcysteine are the most commonly used mucolytics licensed in the United Kingdom (UK) for respiratory conditions.4 Erdosteine is also a licensed mucolytic available for prescription in the UK and is used in short bursts where long term mucolytic therapy is not indicated. At present it should be noted that mucolytics are not recommended for use in an acute exacerbation,4 but some people may benefit from a short course of a mucolytic: this decision should be made on an individual basis.

Carbocisteine

Carbocisteine is perhaps the most well known of the mucolytics currently available to prescribe in the UK. It has the advantage of being familiar to most practitioners and has no notable drug interactions to consider. Another benefit of carbocisteine is the lack of common side effects, though rarely it has been associated with gastrointestinal bleed and allergic reaction.8 It would be therefore inappropriate to prescribe it to those with an active peptic ulcer and anyone with known hypersensitivity to any of its components.

Carbocisteine is usually trialed at a higher dose before being titrated down. The initial dose is 2250mg a day, which is then reduced to 1500mg daily, i.e. two capsules three times a day reducing to two capsules twice a day (or one capsule four times a day) when a satisfactory response is obtained.8 However, a concern regarding carbocisteine is how frequently the trial is not reviewed and dose is not titrated down. This means that many patients will continue to use 180 capsules per month, compared with the 120 capsules required for maintenance.

It is also of note that carbocisteine capsules contain both gelatin and lactose, which can be an issue for some patients, and they are quite large and can be difficult to swallow.9 There are liquid and dissolvable forms to overcome this problem, but these formulations are significantly more expensive than the standard capsules, a cost increase which prescribers should take into account (Table 1). Carbocisteine is available as a generic product and its price is regulated by the Drug Tariff.

N-acetylcysteine

Until recently, N-acetylcysteine has not been licensed in the UK despite being widely used in Europe. It has the advantage of being a once-daily treatment, taken dissolved in water, which makes it acceptable to people who struggle with swallowing large capsules. When compared with carbocisteine, the pill burden is greatly reduced: the patient requires only 30 effervescent tablets per month (one per day) as opposed to a minimum of 120 capsules per month from the start and titration is not needed.10

N-acetylcysteine has no common side effects. Uncommonly, hypersensitivity, headache, pyrexia, hypotension, gastric irritation and tinnitus have been reported, and very rarely, dyspepsia may occur.10

N-acetylcysteine is contraindicated in people with hypersensitivity to any of its components.

N-acetylcysteine should not be dissolved in the same solution as any other medicinal product and it should be taken 2 hours before antibiotic use to avoid a risk of inactivation of the antibiotic. Activated charcoal can reduce effect of

N-acetylcysteine and N-acetylcysteine may enhance effect of nitroglycerin, so caution should be exercised for patients using either or both of these medications.10

N-acetylcysteine products have a significant range in price and it is therefore important to select the brand with the lowest acquisition cost. When appropriately selected, N-acetylcysteine is similarly priced to the usual maintenance dose of carbocisteine, but considerable cost savings are seen where the dose of carbocisteine is not down-titrated, or where non-capsule forms are required. In Scotland, the cost savings with N-acetylcysteine are substantial compared with all doses of carbocisteine due to the higher Drug Tariff price in Scotland.

Erdosteine

Erdosteine is licensed for use in acute exacerbations of chronic bronchitis in people over 18 years of age. It can be used for a maximum of 10 days and then must be stopped. The usual dosage is 300mg twice daily and it is supplied, like carbocisteine, in capsule form which poses difficulty for people who are unable to swallow capsules.11 However, as this is a short course of treatment the pill burden is less a disadvantage than it would be in a long term treatment. Erdosteine is best used in those who do not routinely struggle with expectoration but are having difficulties with expectoration during an acute exacerbation, which can hinder recovery.1 Erdosteine over 10 days’ use costs more than twice as much as a 10-day supply of other mucolytics and this should be considered when prescribing. Erdosteine is contraindicated in those with liver or renal failure (creatinine clearance of less than 25ml/min) and in those with hypersensitivity to any components of the medicine or active peptic ulcer.10 It is not known to interact with any other medications. The most commonly reported side effect is gastrointestinal disorder. Uncommon side effects include colds, dyspnoea, headaches, gastric irritation, taste alteration and hypersensitivity reactions such as urticarial.10

An advantage erdosteine has is that, like N-acetylcysteine, it has no titration period and unlike either carbocisteine or

N-acetylcysteine, review is not usually required as this is not a medicine which will continue after the initial period of use. Where a trial of carbocisteine or

N-acetylcysteine has been reviewed and discontinued due to lack of perceived/ objective benefit, erdosteine may be a useful alternative for a patient who requires mucolytic treatment during periods of exacerbation then but not in periods of wellness.

CONCLUSION

Mucus accumulation in the airways can pose several problems for people with COPD.1 Those effected with symptoms of chronic bronchitis and those not treated with inhaled corticosteroids are most likely to benefit from a mucolytic.5 Before considering pharmacological intervention, it is advisable to ensure that practical lifestyle advice and non-pharmacological intervention have been considered as these do not entail a cost burden to the NHS or pill burden to the person with COPD, do not carry the risk of side effects and do not add to the problem of polypharmacy.4

Identifying appropriate candidates for mucolytic therapy is essential to avoid unnecessary cost to the NHS, unnecessary risk to the person with COPD, and to ensure safe and optimal prescribing. It is recognised that mucolytics are not beneficial to all COPD patients, even among those experiencing chronic bronchitis-type symptoms, which is why mucolytics are not recommended as standard therapy for all patients with COPD. The importance of review if initiating a trial of long-term mucolytic therapy cannot be over-stated.8 This is particularly true where the pill burden and cost of medication that has not been titrated is significant, as is the case with carbocisteine. Stopping long-term mucolytics where no improvement is seen is important, and making an objective decision can be aided by symptom scoring tools such as CAT.

Where a person is suitable for mucolytics, the practitioner should carefully consider the options available. It is of paramount importance to consider the individual’s circumstances, both health and non-health related, in order to select and prescribe the medication which is most suitable. Taking into account non-medical factors such as the potential for medication review, ability to remember medicines and financial cost to the NHS are important as well as the pharmacological suitability of a given drug. This should be the case in prescribing any medication and is no less true for mucolytics.

REFERENCES

1. Cazzola M, Rogliani P, Calzetta L, et al. Impact of Mucolytic Agents on COPD Exacerbations: A Pair-wise and Network Meta-analysis. COPD: J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2017;14(5):552-563.

2. Ramos FL, Krahnke JS, Kim V. Clinical issues of mucus accumulation in COPD. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2014;9:139–150.

3. Ito JT, Ramos D, Lima FF, et al. Nasal Mucociliary Clearance in Subjects With COPD After Smoking Cessation: Respiratory care .2015; 60(3), 399-405

4. NICE NG115. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in over 16s: diagnosis and management, December 2018. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng115

5. GOLD. 2019 Global Strategy For Prevention, Diagnosis and Management of COPD [Internet], December 2018 https://goldcopd.org

6. NHS Choices. Water, drinks and your health, 2018 https://www.nhs.uk/live-well/eat-well/water-drinks-nutrition/

7. Association of Chartered Physiotherapists in Respiratory Care (ACPRC). The Active Cycle of Breathing Techniques, 2011. https://www.acprc.org.uk/Data/Publication_Downloads/GL-05ACBT.pdf

8. Carbocisteine 375 mg Capsules, Summary of product characteristics. Last updated, August 2018. https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/product/3291/smpc

9. Hamilton AR, Murphy A. Carbocisteine: Are we getting it right?. University Hospitals of Leicestershire NHS Trust, 2015

10. NACSYS 600mg Effervescent Tablets, Summary of product characteristics. Last updated October 2017. https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/product/8576

11. Erdotin 300mg capsules, Summary of product characteristics. Last updated July 2017. https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/product/287

Related articles

View all Articles