Managing the long-term effects of COVID-19

NICE NG188; 18 December 2020

NICE NG188; 18 December 2020

For most people the symptoms of COVID-19 resolve within 12 weeks. But for a sizeable minority, symptoms can persist or new ones develop. Longer term effects of COVID-19 may include shortness of breath, fatigue, and ongoing problems involving the heart, lungs, kidneys, nervous system, and muscles and joints

This guideline covers the identification, assessment and management of the long-term effects of COVID-19, often described as ‘long COVID’. It was developed jointly by NICE, SIGN and the RCGP, and is a ‘living’ guideline, which means that target areas will be continually reviewed and updated in response to emerging evidence.

The guideline makes recommendations in a number of areas, including:

- Assessing people with new or ongoing symptoms after acute COVID-19

- Investigations and referral

- Planning care

- Management (including self-management, supported self-management, and rehabilitation)

- Follow up and monitoring

Acute COVID-19 is defined as signs and symptoms that last for up to 4 weeks. Ongoing symptomatic COVID-19 (symptoms persisting from 4 to 12 weeks) and post-COVID-19 syndrome (signs and symptoms that develop during or after COVID-19 infection, continue for more than 12 weeks, and are not explained by an alternative diagnosis) are together commonly known as ‘long COVID’. It usually presents with clusters of symptoms, often overlapping, which can fluctuate and change over time, and can affect any body system.

COMMON SYMPTOMS

Respiratory symptoms

- Breathlessness

- Cough

Cardiovascular symptoms

- Chest tightness

- Chest pain

- Palpitations

Generalised symptoms

- Fatigue

- Fever

- Pain

Neurological symptoms

- Cognitive impairment (‘brain fog’, loss of concentration or memory issues)

- Headache

- Sleep disturbance

- Peripheral neuropathy (pins and needles, numbness)

- Dizziness

- Delirium (in older people)

Gastrointestinal symptoms

- Abdominal pain

- Nausea

- Diarrhoea

- Anorexia and reduced appetite (in older people)

Musculoskeletal symptoms

- Joint pain

- Muscle pain

Psychological/psychiatric symptoms

- Depression

- Anxiety

Ear, nose and throat symptoms

- Tinnitus

- Earache

- Sore throat

- Dizziness

- Loss of taste and/or smell

Dermatological

- Skin rashes

ASSESSING PEOPLE WITH NEW OR ONGOING SYMPTOMS AFTER ACUTE COVID-19

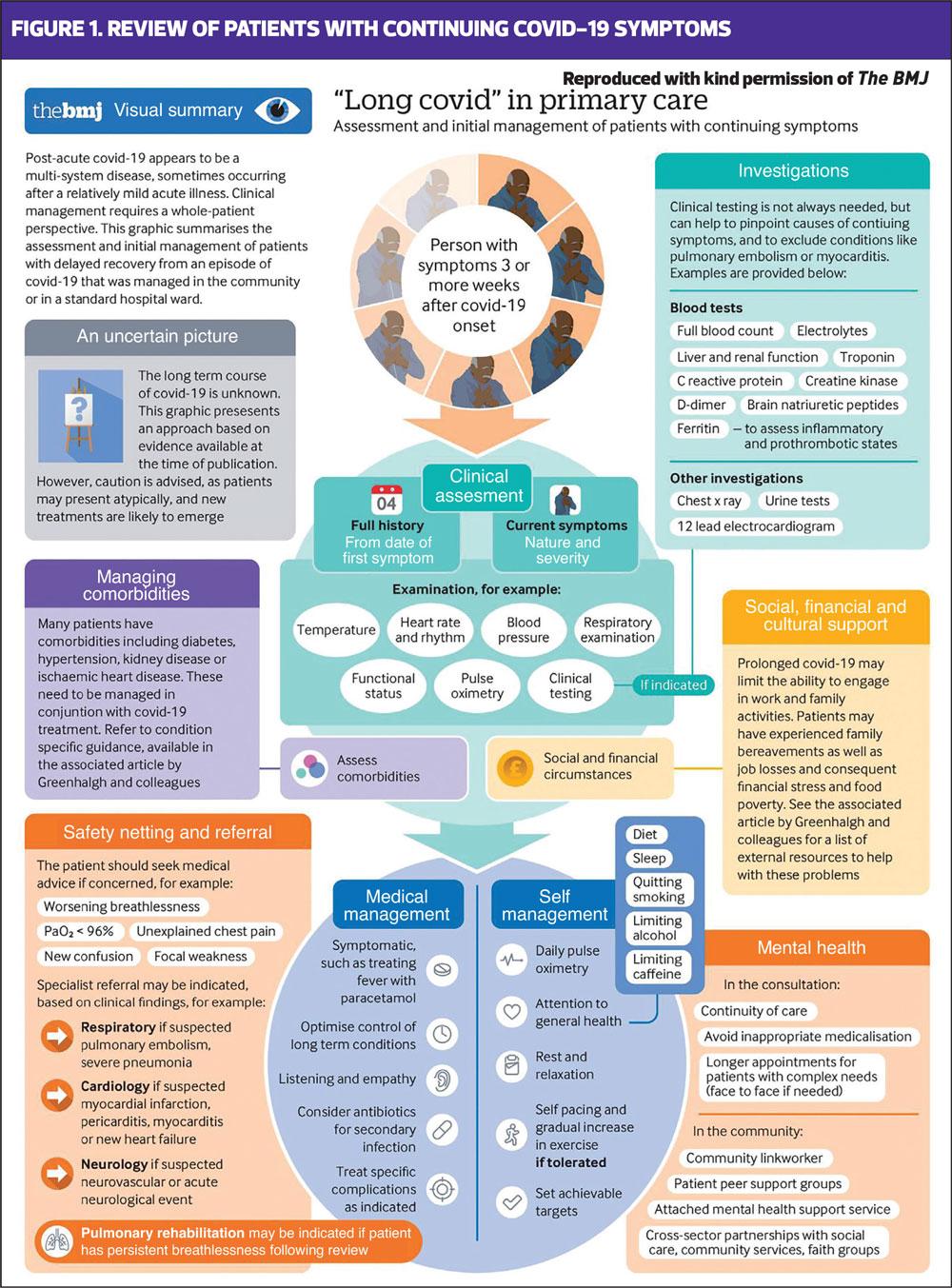

For people with ongoing symptomatic COVID-19 or suspected post-COVID-19 syndrome, take a holistic, person-centred approach. Take a comprehensive clinical history, and carry out an appropriate examination that involves assessing physical, cognitive, psychological and psychiatric symptoms, and functional abilities.

The history should cover:

- History of suspected or confirmed acute COVID-19

- The nature and severity of previous and current symptoms

- Timing and duration of symptoms

- History of other health conditions.

Be aware that symptoms may be wide-ranging and may fluctuate over time. You should discuss how the person’s life and activities, e.g. work or education, mobility and independence have been affected by their symptoms, acknowledge the impact of their illness on day-to-day life, and listen to their concerns. Do not attempt to predict whether someone is likely to develop long COVID based on whether they had specific symptoms or were hospitalised during the acute illness.

If you are investigating possible causes of a gradual decline, worsening frailty or dementia, or loss of interest in eating and drinking in older people, bear in mind that these can be signs of ongoing symptomatic COVID-19. If someone reports new cognitive symptoms, use a validated screening tool to measure impairment and impact.

INVESTIGATIONS AND REFERRAL

No one set of investigations and tests is suitable for everyone with ongoing symptomatic COVID-19 or suspected post-COVID-19 syndrome because of the wide range of symptoms and severity. Investigations should be tailored to the individual’s signs and symptoms. Many of the tests suggested below can be carried out in primary care. However, patients should be referred urgently to the relevant acute services if they have signs or symptoms that could be caused by a life-threatening complication, such as:

- Severe hypoxaemia or oxygen desaturation on exercise

- Signs of severe lung disease

- Cardiac chest pain

- Multisystem inflammatory syndrome (in children)

Offer tests and investigations based on presenting symptoms to establish whether they are likely to be caused by ongoing symptomatic COVID-19 or a new, unrelated diagnosis. If an unrelated diagnosis is suspected, follow the relevant national or local guidance.

Tests may include:

- Blood tests, including full blood count, kidney and liver function tests, C-reactive protein, ferritin, B-type natriuretic peptide and thyroid function tests.

- An exercise tolerance test (e.g. 1-minute sit-to-stand test. Record level of breathlessness, heart rate and oxygen saturation

- Lying and standing blood pressure (for people with postural symptoms)

- Chest X-ray 12 weeks after acute COVID-19 if the patient has not already had one and has continuing respiratory symptoms

Refer people for urgent psychiatric assessment if they have severe psychiatric symptoms or are at risk of self-harm or suicide. Consider referral for psychological therapies for people with mild anxiety or depression, or to a liaison psychiatry service if they have a complex physical and mental health presentation.

After ruling out life-threatening complications and alternative diagnoses, consider referring people to an integrated multidisciplinary assessment service (if available) at any time from 4 weeks after the start of acute COVID-19.

Consider the overall impact of the individual’s symptoms, even each individual symptom alone may not warrant referral.

Do not exclude people from referral to a multidisciplinary assessment service, for further investigations or specialist input based on the absence of a positive SARA-CoV-2 test – many people who had acute COVID-19, especially early in the pandemic, did not have a test.

PLANNING CARE

After assessment, use share decision making to discuss and agree with the person (and their family or carers) what support and rehabilitation they need and how this will be provided.

The discussion should include:

- Self-management of symptoms, such as setting realistic goals

- Who to contact if they are worried about their symptoms or need support

- Sources of advice and support e.g. support groups, social prescribing, online forums

- How to get support from other services such as social care

People may need support in discussions with employer, school or college about returning to work or education, e.g. having a phased return. See NICE’s guideline on workplace health: long-term sickness absence and capability to work https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng146

People may also need referral to a multidisciplinary rehabilitation service, where available, which should include occupational therapy, physiotherapy, clinical psychology and psychiatry, and rehabilitation medicine. These services will have the necessary expertise to treat fatigue and respiratory symptoms, as well as ongoing psychological symptoms, and neurological symptoms such as brain fog.

Older people are likely to need additional support, for example short-term care packages, advance care planning and support with social isolation, loneliness and bereavement as applicable.

Consider referral for specialist advice for children with ongoing symptomatic COVID-19 or post-COVID-19 syndrome from 4 weeks after the acute infection.

FOLLOW UP

Agree with your patient how often follow-up and monitoring are needed and which healthcare professionals should be involved, based on their level of need. It is important that people’s support can be adapted if their symptoms, or ability to carry out usual activities, change. Patients also value the ability to ‘check in’.

Using shared decision making, offer monitoring in person or remotely depending on the patient’s preference and whether it is clinically appropriate. Monitoring should be tailored to the individual’s symptoms, including new or worsening symptoms and their impact on the person’s life and wellbeing.

Heart rate, pulse oximetry and blood pressure can be self-monitored at home: ensure that the individual has clear instructions on when to seek further help. Self-monitoring is widely used in practice, but may not be suitable for everyone and can increase anxiety without the right information and support.

Be alert to developing or deteriorating symptoms that could mean referral or investigation is needed.

FURTHER READING

Bostock B. Long COVID – what should primary care be doing? Practice Nurse 2020;50(8):11–15

Reference

NICE NG188. COVID-19 rapid guideline: managing the long-term effects of COVID-19; 18 December 2020 https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng188

Related guidelines

View all Guidelines