COPD: GOLD 2020

Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD). Global strategy for the diagnosis, ma...

Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD). Global strategy for the diagnosis, management and prevention of COPD. 2020 Report; 2019.

The 2020 report updates recommendations in a number of areas, but for completeness, this summary covers the main aspects of COPD that are likely to be managed in primary care, which will be particularly useful for practice nurses who are not ‘experts’ – and those who would appreciate a refresher on the basics of COPD management

The first Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) report was published in 2001, since when it has been updated annually with a major revision every five years. The last major report was in 2017.

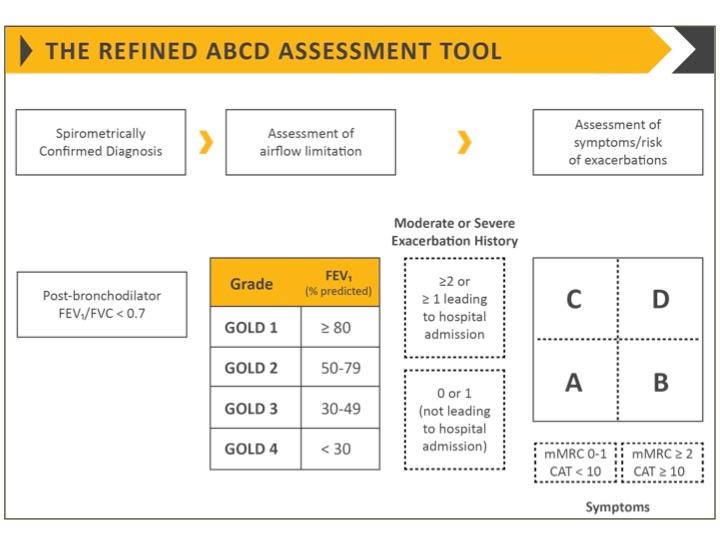

The 2020 report retains the ‘refined’ ABCD assessment tool from the 2017 revision, and emphasises the importance of the individual patient’s symptoms and exacerbation risks, and separates recommendations for initial and follow up treatment based on the patient’s major treatable traits. The 2020 revision also refines the use of non-pharmacological treatments, adds more information on the role of eosinophils as a biomarker for the efficacy of inhaled corticosteroids (ICSP and clarifies the diagnosis of exacerbations.

The term asthma & COPD overlap (ACO) is no longer used, as asthma and COPD are different conditions, although they may share some common characteristics and clinical features.

DEFINITION & OVERVIEW

COPD is a common, preventable and treatable disease, characterised by persistent respiratory symptoms and airflow limitation due to airway and/or alveolar abnormalities, usually caused by significant exposure to noxious particles or gases. The main risk factor for COPD is tobacco smoking but biomass fuel exposure and air pollution may be contributory factors. ‘Host’ factors include genetic abnormalities, abnormal lung development and accelerated ageing.

The most common respiratory symptoms include dyspnoea, cough and/or sputum production. These symptoms may be under-reported by patients.

COPD is associated with periods of acute worsening of symptoms (exacerbations), and in most patients, is associated with significant comorbidities which increase morbidity and mortality.

COPD is a leading cause of morbidity and mortality worldwide. Prevalence – currently estimated at 12% globally – is projected to increase due to continued exposure to risk factors and an ageing population.

DIAGNOSIS & INITIAL ASSESSMENT

COPD should be considered in any patient who has dyspnoea (progressive over time, characteristically worse with exercise, persistent), chronic cough or sputum production, a history of recurrent lower respiratory tract infections and/or a history of risk factors for the disease.

Chronic cough is not specific to COPD, so consider other causes, which include:

- Asthma

- Lung cancer

- Tuberculosis

- Brochiectasis

- Left ventricular heart failure

- Interstitial Lung Disease

- Cystic fibrosis

- Idiopathic Cough

- Chronic allergic rhinitis

- Post nasal drip syndrome

- Upper airway cough syndrome

- Gastro-eosophageal reflux

- Medication (e.g. ACE inhibitors)

Additional signs in severe COPD include fatigue, weight loss and anorexia; these can also be a sign of other diseases including TB and lung cancer, so should always be investigated. Ankle swelling may indicate the presence of cor pulmonale.

Comorbidities frequent occur in patients with COPD, including cardiovascular disease, skeletal muscle dysfunction, metabolic syndrome, osteoporosis, depression, anxiety and lung cancer. These conditions should be actively sought and treated as they can independently affect the risk of hospitalisation and mortality.

Spirometry is required to make the diagnosis. A post-bronchdilator FEV1/FVC <0.70 confirms the presence of persistent airflow limitation.

- Spirometers should be calibrated regularly

- Spirometry should be performed by a person who has been trained in optimal technique and quality performance

- Maximal patient effort in performing the test is needed to avoid underestimation of values and hence errors in diagnosis and management.

For reversibility testing, measure FEV1 10-15 minutes after a short-acting B2 agonist (SABA) is given, or 30-45 minutes after a short-acting anti muscarinic (SAMA) or a combination of both classes of drug. The threshold for airflow diagnosis is a post-bronchodilator fixed ratio of FEV1/FVC <0.70.*

*GOLD prefers this criterion to lower limit of normal (LLN) as it is independent of reference values, even though it may result in more frequent diagnosis in elderly patients, and less frequent diagnosis in adults

Assessment should determine the level of airflow limitation, the impact of disease on the patient’s health status, and the risk of future exacerbations, hospital admissions, or death, in order to guide treatment.

Classification of airflow limitation

- GOLD 1: Mild – FEV1 ≥80% predicted

- GOLD 2: Moderate – 50% ≤FEV1 <80% predicted

- GOLD 3: Severe – 30% ≤FEV1 <50% predicted

- GOLD 4: Very severe – FEV1 <30% predicted

In addition to assessing breathlessness using the Modified Medical Research Council (mMRC) dyspnoea scale, assess health status using the COPD Assessment Test (CAT) or the COPD Control Questionnaire.

When assessing the risk of future exacerbations, the best predictors of frequent exacerbations (two or more per year) are:

- A history of previous, treated exacerbations

- Deteriorating airflow limitation, and

- Spirometric severity.

See Figure 1.The number (GOLD 1, GOLD 2, etc) indicates severity of airflow limitation, while the letter (A – D) provides information on symptom burden and risk of exacerbation.

PREVENTION AND MANAGEMENT

- Smoking cessation is key. Pharmacotherapy and nicotine replacement increase long-term abstinence rates. The effectiveness and safety of e-cigarettes as an aid to smoking cessation is uncertain.

- Pharmacological therapy can reduce COPD symptoms, reduce the frequency and severity of exacerbations, and improve health status and exercise tolerance.

- Each treatment regime should be individualised and guided by severity of symptoms, risk of exacerbations, side effects, comorbidities, and the patient’s response, preference and ability to use inhaler devices.

- Assess inhaler technique regularly

- Flu vaccination and pneumococcal vaccination decrease the incidence of lower respiratory tract infections

- Pulmonary rehabilitation improves symptoms, quality of life, and physical and emotional participation in everyday activities

- For patients with severe COPD, refer to the full guideline recommendations for long-term oxygen therapy, non-invasive ventilation, surgical or bronchoscopic interventions, and palliative care.

Pharmacotherapy

The aims of drug therapy for COPD are to reduce symptoms, reduce the frequency and severity of exacerbations, and to improve exercise tolerance and health status

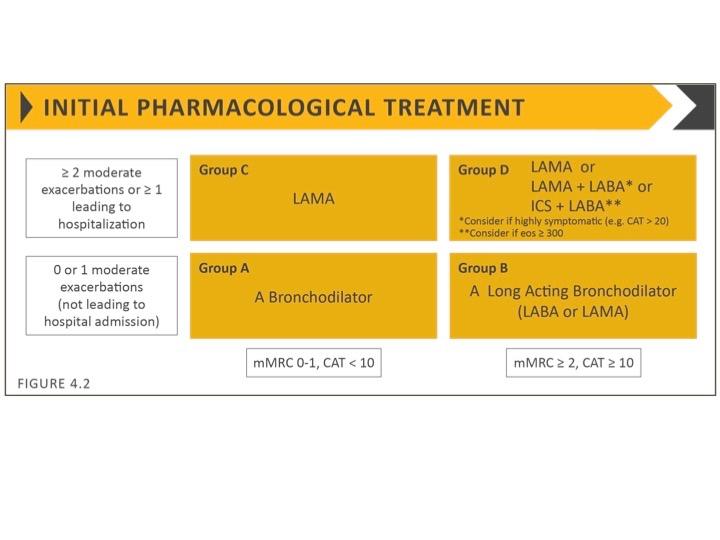

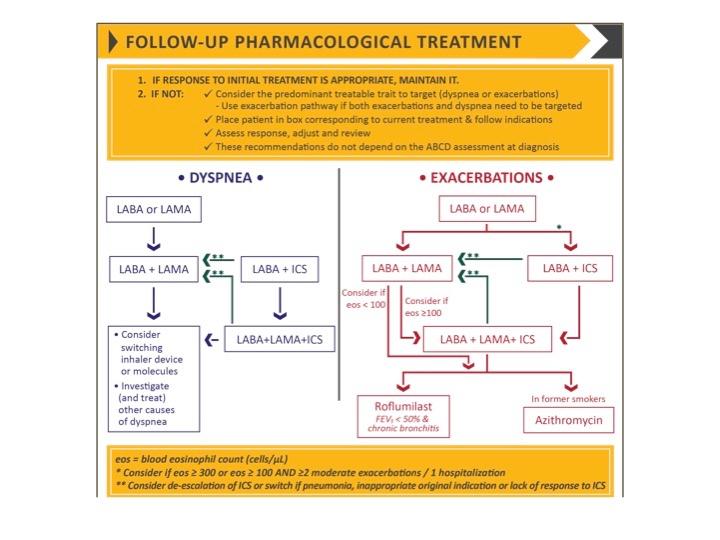

Inhaled bronchodilators are central to symptom management and used regularly to prevent or reduce symptoms. See Figure 2.

- Regular and as-needed use of SABA or SAMA improves lung function and symptoms.

- Combinations of SABA and SAMA are more effective than either medication alone.

- Long-acting bronchodilators (LABA) and anti-muscarinic agents (LAMAs) significantly improve lung function, dyspnoea, and health status, and reduce exacerbation rates

- Combination treatment with a LABA and LAMA increases FEV1, and reduces symptoms and exacerbations compared with monotherapy.

- ICS in combination with a LABA is more effective than the individual components

- Regular ICS treatment increases the risk of pneumonia, especially in patients with severe COPD

- Triple inhaled therapy (ICS/LAMA/LABA) increases FEV1, and reduces symptoms and exacerbations compared with ICS/LABA, LABA/LAMA or LAMA monotherapy

- In patients with chronic bronchitis, severe to very severe COPD and a history of exacerbations, a PDE4 inhibitor (e.g. roflumislast [Daxas])

- Long-term antibiotics (azithromycin and erythromycin) reduce exacerbations over one year, but treatment with azithromycin is associated with an increased incidence of bacterial resistance.

- Regular treatment with mucolytics (erdosteine, carbocysteine, NAC) reduces exacerbations in some populations.

- Simvastatin does not prevent exacerbations in COPD patients at increased risk of exacerbations and without indications for statin therapy. However, statins may have some benefits for COPD patients who are prescribed them for cardiovascular and metabolic indications.

Blood eosinophil count

Blood eosinophil counts predict the effect of ICS (added to regular bronchodilator treatment) in preventing future exacerbations. ICS-containing regimens have little or no effect at a blood easonophil count 300 cells/μl are likely to benefit most. These thresholds should be not be regarded as cut-off points, but as a guide to predicting possible treatment benefit.

Factors to consider when initiating ICS

Factors strongly supporting ICS initiation include:

- History of hospitalisation(s) for exacerbations

- Two or more moderate exacerbations per year (despite appropriate long-acting bronchodilator maintenance therapy)

- Blood eosinophils >300 cells/μl

- History of, or comorbid asthma

Consider ICS use when:

- One moderate exacerbation of COPD per year (despite appropriate long-acting bronchodilator maintenance therapy)

- Blood eosinophils 100-300 cells/μl

Factors mitigating against the use of ICS:

- Repeated pneumonia events

- Blood eosinophils

- History of myocardial infarction

INHALER DEVICES

When a treatment is given by inhaler, the importance of education and training in inhaler device technique cannot be over-emphasised.

The choice of device should be tailored to the individual and most importantly, will depend on the patient’s ability and preference.

It is essential to provide instructions and to demonstrate the proper inhaler technique when prescribing any device, to ensure technique is adequate. Technique should be re-checked at every visit to ensure that patients continue to use their inhaler correctly.

Inhaler technique – and adherence to therapy – should be assessed before making changes to therapy on the basis that current treatment is insufficient.

The main errors in technique relate to problems with inspiratory flow, inhalation duration, co-ordination, dose preparation, exhalation manoeuvre before inhalation, and breath-holding following inhalation. Specific instructions are available for each type of device.

There is no evidence of superiority of nebulised therapy over hand-held devices in patients who are able to use them properly.

NON-PHARMACOLOGICAL TREATMENT

Pulmonary rehabilitation

Pulmonary rehabilitation should be considered part of integrated patient management. Benefits to patients are considerable, in terms of improving breathlessness, health status and exercise tolerance. Pulmonary rehabilitation also reduces hospitalisation among patients who have had a recent exacerbation, and leads to a reduction in symptoms of anxiety and depression. However, uptake is often poor – either because patients have not been referred for rehabilitation or because they are unaware of the potential benefits.

Education

Patient education often takes the form of healthcare professionals giving information and advice, and assuming that knowledge will lead to behaviour change. Improving patient knowledge is important, but education alone has not been shown to be effective in changing behaviour or even motivating patients. Self-management interventions that are structured and personalised, such as health coaching, may be useful. Topics that should be covered in this way include:

- Smoking cessation

- Correct use of inhaler devices

- Early recognition of exacerbation

- When to seek help

- Considering advance directives.

Vaccination

Annual flu vaccination is recommended for all patients with COPD, and patients >65 years (and younger patients with significant comorbidities e.g. heart disease) should receive the one-off pneumococcal vaccination.

Nutrition

Nutritional supplementation should be considered in malnourished patients with COPD.

Oxygen therapy

Long-term oxygen therapy is recommended for patients with severe resting hypoxaemia, but should not be routinely prescribed for patients with stable COPD and resting or exercise-induced, modest desaturation. Individual patient factors should be considered. Be aware that resting oxygenation at sea level does not preclude severe hypoxaemia when traveling by air.

MANAGEMENT CYCLE

After the start of therapy, patients should be re-assessed for progress towards treatment goals:

- Review: Symptoms - especially breathlessness, and exacerbations

- Assess inhaler technique and adherence, non-pharmacological approached (including pulmonsary rehabilitation and self-management education)

- Adjust therapy as necessary: escalate, switch inhaler device or inhaled drug(s), de-escalate

A separate algorithm is provided for follow-up treatment, where management is still based on symptoms and exacerbations, but recommendations are not dependent on the patient's GOLD group at diagnosis. See Figure 3.

FOLLOW-UP

Routine follow-up of patients with COPD is essential. Lung function may worsen over time, even with optimal care. Symptoms, exacerbations and objective measures of airflow limitation should monitored to modify management, and identify any complications or comorbidities that may develop.

Each follow-up visit should include:

- Dosage of prescribed medications

- Adherences

- Inhaler technique

- Effectiveness of current regime

- Side effects.

MANAGEMENT OF EXACERBATIONS

An exacerbation of COPD is defined as an acute worsening of respiratory symptoms that results in additional therapy.

As the symptoms are not specific to COPD, relevant differential diagnoses should be considered.

Exacerbations can be precipitated by several factors, most commonly respiratory tract infections

The goal of treatment is to minimise the impact of the current exacerbation and prevent subsequent events. Symptoms usually last between 7 and 10 days, but at 8 weeks, 20% of patients have not recovered to their pre-exacerbation state.

SABA, with or without SAMA, is recommended as the initial bronchodilators to treat an acute exacerbation. Maintenance therapy with a long-acting bronchodilator should be initiated as soon as possible (before hospital discharge if admitted).

Oral corticosteroids (OCS) can improve lung function and oxygenation, and shorten recovery time and length of hospital stay. Prednisalone 40mg/day for 5 days is recommended. OCS should be prescribed for no more than 5–7 days as longer courses increase risk of pneumonia.

Antibiotics can shorten recovery time, reduce the risk of early relapse, treatment failure, and length of hospital stay. Indications for antibiotics are the three cardinal symptoms: increase in dyspnoea, sputum volume and sputum prurulence (or two of these if one is increased sputum prurulence). Antibiotics should be continued for 5–7 days. Choice of antibiotic should be guided by local bacterial resistance pattern.

Consider admission for patients with:

- Severe symptoms such as sudden worsening of resting dyspnoea, high respiratory rate, decreased oxygen saturation, confusion or drowsiness

- Acute respiratory failure

- Onset of new physical signs (e.g. cyanosis, peripheral oedema)

- Failure to respond to initial management

- Presence of serious comorbidities

- Insufficient home support

Differential diagnosis of COPD exacerbation

When there is clinical suspicion of the following acute conditions, consider further investigation:

- Pneumonia

- Chest X-ray

- Assessment of C-reactive protein (CRP) (and/or procalcitonin if available)

- Pneumothorax

- Chest X-ray or ultrasound

- Pleural effusion

- Chest X-ray or ultrasound

- Pulmonary embolism

- D-dimer and/or Doppler sonography

- Computed tomography pulmonary angiogram (CTPA)

- Pulmonary oedema (cardiac related)

- Electrocardiogram (ECG) and cardiac ultrasound

- Cardiac arrhythmias (atrial fibrillation)

- ECG

The above summary covers those aspects of COPD that are likely to be managed in primary care. For more detailed recommendations and further information on the management of severe disease, view the full guideline at https://goldcopd.org/gold-reports/

Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD). Global strategy for the diagnosis, management and prevention of COPD. 2020 Report; 2019. https://goldcopd.org/gold-reports/

Related guidelines

View all Guidelines