British Guideline on the Management of Asthma, 2019

British Thoracic Society/Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network, 24 July 2019 (SIGN 158)

British Thoracic Society/Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network, 24 July 2019 (SIGN 158)

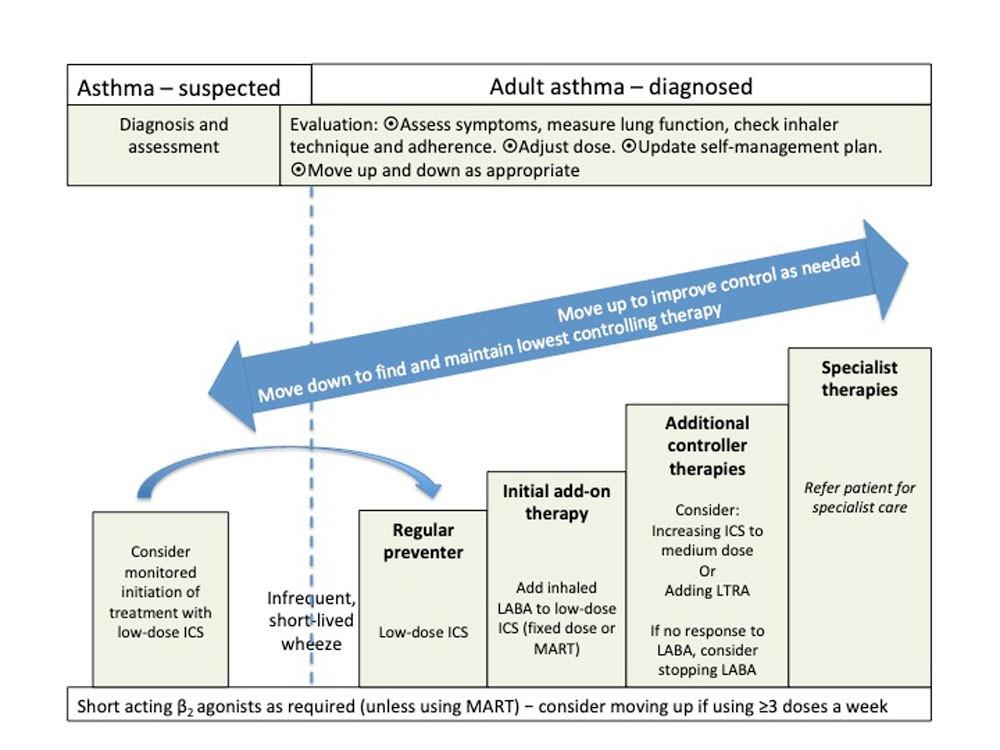

The 2019 BTS/SIGN Guideline provides a simplified approach to treatment to ensure that all patients with asthma are prescribed an inhaled corticosteroid (ICS) and that treatment for any patient using more than three doses of a short-acting bronchodilator a week is stepped up

The updated version of the British Guideline on the Management of Asthma was launched last month (July 2019) is likely to be the last produced by the British Thoracic Society and the Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network, independently of NICE. In future UK-wide guidance for the diagnosis and management of chronic asthma will be produced jointly by the three organisations to:

- Support healthcare professionals in making accurate diagnoses and providing effective treatments to control the condition and prevent acute asthma attacks

- Promote good practice and include recommendations in areas where differences in guidance had previously existed between the organisations.

The new guideline will form part of a broader set of guidance and materials produced by BTS, SIGN and NICE, on diagnosing and management asthma throughout an individual’s lifetime – a new ‘asthma pathway’.

THE NEW BTS/SIGN GUIDELINE

The new BTS/SIGN Guideline provides a simplified approach to treatment to ensure that all patients with asthma are prescribed an inhaled corticosteroid (ICS) and that treatment for any patient using more than three doses of a short-acting bronchodilator a week is stepped up.

The first choice as an add-on therapy to ICS is an inhaled long-acting β2 agonist (LABA), which should be considered before increasing the dose of ICS.

The guideline also stresses the importance of assessing the risk of future asthma attacks at every asthma review by asking about the history of previous attacks, objectively assessing current asthma control and reviewing reliever use.

Quadrupling the dose of ICS is recommended as a means of averting an acute asthma attack.

Good asthma control is associated with little or no need for short-acting β2 agonist (SABA). SABA should only be used as required for the relief of symptoms.

Anyone prescribed more than one short-acting bronchodilator inhaler device a month should be identified and have their asthma assessed urgently, and measures taken to improve asthma control if this is poor

Ed: This advice has since been updated. Anyone requiring more three SABA inhalers a year should be assess urgently and measures taken to improve asthma control

DIAGNOSIS

Central to all definitions of asthma is the presence of symptoms – one or more of wheeze, breathlessness, chest tightness, cough – and of variable airflow obstruction. There is no single diagnostic test for asthma: diagnosis is based on clinical assessment supported by objective tests that demonstrate variable airflow obstruction or the presence of airway inflammation.

In a patient with a very high probability of asthma prior to testing, the results of a diagnostic test with a substantial false negative rate will have minimal influence. Conversely, in a patient with an intermediate or low probability of asthma, a positive diagnostic test may significantly shift the probability towards an asthma diagnosis.

Diagnostic tests are typically performed at a single point of time whereas asthma status varies over time. Objective tests performed when patients are asymptomatic may result in false negatives: for example, spirometry in primary care patients with intermittent symptoms confirms obstruction in less than 40% of patients, and bronchodilator reversibility is demonstrated in around 15% of patients – whereas in patients admitted to hospital with a confirmed asthma attack, 83% had obstructive lung function. Similarly, fractional exhaled nitric oxide (FeNO) was only positive in 40% with diagnosed asthma at 12 months, and one in five were falsely negative.

Recommendation

Compare the results of diagnostic tests undertaken while a patient is asymptomatic with those undertaken when a patient is symptomatic to detect variation over time

Spirometry

Spirometry is the investigation of choice for the identification of airflow obstruction and is widely available although training is needed to obtain reliable recordings and to interpret the results, particularly in children.

Measuring lung function in children under 5 years is difficult and requires specialist techniques. In children over 5 conventional lung function testing is possible in most settings by an operator experienced in paediatric spirometry. FEV1 is often normal in children with persistent asthma, and abnormal results may be seen in children with other respiratory diseases.

Forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1)/forced vital capacity (FVC) can be as high as 90% in young children, so using the commonly used fixed ratio of 70% will underestimate airflow limitation. In adults over 40 years, levels below 70% may be normal, and using a 70% threshold will overestimate obstruction.

In adults with obstructive spirometry, an improvement in FEV1 of 12% or more in response to either β2 agonists or ICS treatment trials, together with an increase in volume of 200ml or more is regarded as a positive test. Note: some people with COPD can have significant reversibility.

In children, an improvement in FEV1 of 12% or more is regarded as a positive test

Recommendation

Carry out quality-assured spirometry using lower limits of normal to demonstrate airway obstruction, provide a baseline for assessing response to initiation of treatment and exclude alternative diagnoses

- Obstructive spirometry with positive bronchodilator reversibility increases the probability of asthma

- Normal spirometry in an asymptomatic patient does not rule out the diagnosis of asthma

Peak expiratory flow monitoring

- A peak flow recorded when symptomatic (e.g. during the assessment of an asthma attack) may be compared with peak flow when asymptomatic (e.g. after recovery from an attack) to confirm variability

- In adults, serial peak-flow records may demonstrate variability in symptomatic patients but should be interpreted with caution, and in context. There is no evidence to support routine use of peak-flow monitoring in the diagnosis of asthma in children.

- Serial peak flows (at least four readings a day) are the initial investigation of choice in suspected occupational asthma

Challenge tests

Referral for challenge tests (direct or indirect) should be considered in adults with no evidence of airflow obstruction on initial assessment in whom other objective tests are inconclusive but asthma remains a possibility.

Fractional exhaled nitric oxide (FeNO)

A positive FeNO tests suggests eosinophilic inflammation and provides supportive but not conclusive evidence for an asthma diagnosis.

FeNO levels are:

- Increased in patients with allergic rhinitis exposed to allergen, even without respiratory symptoms

- Increased by rhinovirus infection in healthy individuals but this effect is inconsistent in people with asthma

- Increased in men, tall people, and by consumption of dietary nitrates

- Lower in children

- Reduced in cigarette smokers

- Reduced by inhaled or oral steroids

In steroid-naïve adults, a FeNO of 40 parts per billion (ppb) or more is regarded as positive; in schoolchildren, a FeNO level of 35 ppb or more is regarded as a positive test.

Recommendation

Use measurement of FeNO (if available) to find evidence of eosinophilic inflammation. A positive test increases the probability of asthma but a negative test does not exclude asthma

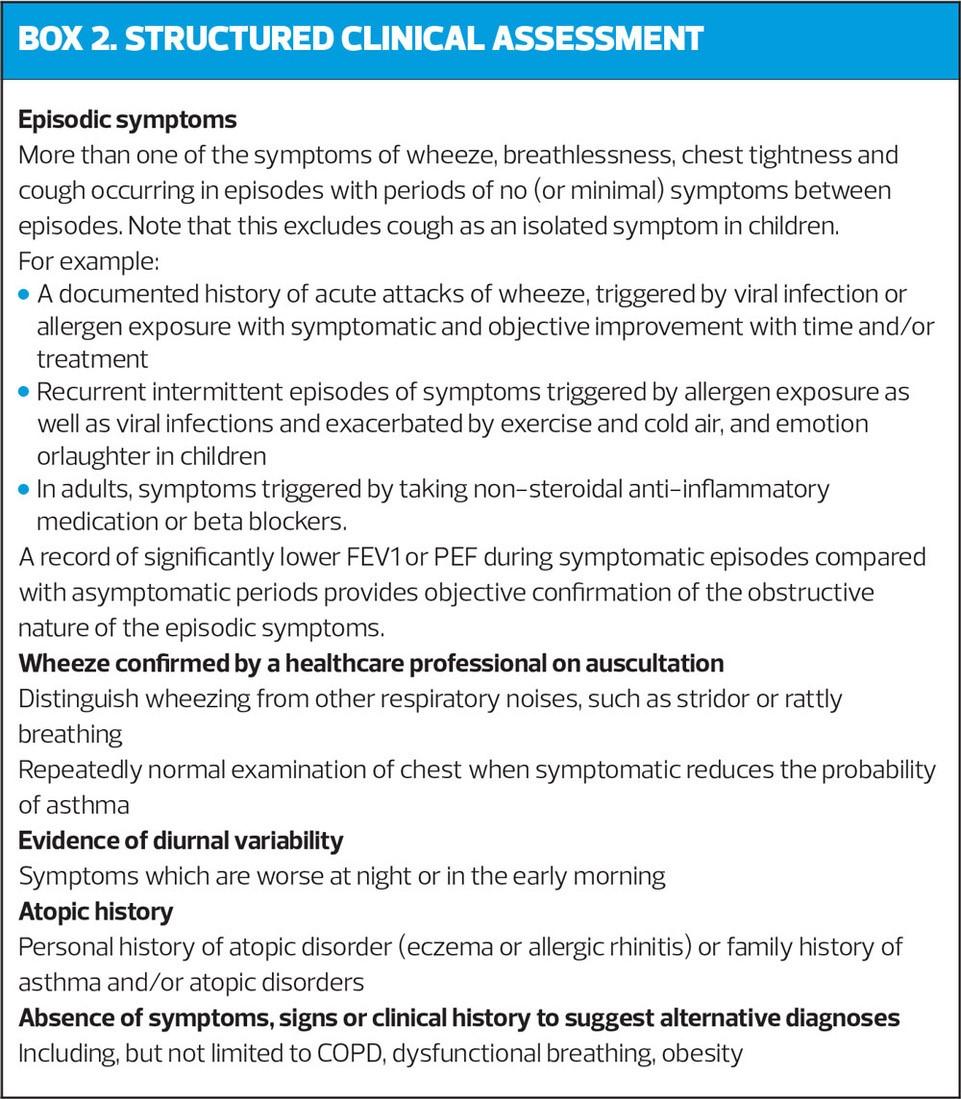

STRUCTURED CLINICAL ASSESSMENT

Undertake a structured clinical assessment to assess the initial probability of asthma, (Box 2) based on:

- History of recurrent episodes of symptoms, ideally corroborated by variable peak flows when symptomatic and asymptomatic

- Symptoms of wheeze, cough, breathlessness and chest tightness that vary over time

- Recorded observation of wheeze by healthcare professional

- Personal/family history of other atopic conditions

- No symptoms or signs to suggest alternative diagnoses

PROBABILITY OF ASTHMA BASED ON INITIAL STRUCTURED CLINICAL ASSESSMENT

High probability

Record the patient as likely to have asthma, code as suspected asthma, and commence carefully monitored initiation of treatment (typically 6 weeks of ICS)

Assess baseline status using a validated question (Asthma Control Questionnaire or Asthma Control Test and lung function tests (spirometry or peak expiratory flow)

At follow-up, assess symptomatic response and lung function

If response is good (clinically important improvement and/or substantial increase in lung function), confirm diagnosis.

Adjust treatment according to the response (down-titrate ICS dose) to the lowest dose that maintains the patient free of symptoms.

Provide self-management education and a personalised asthma action plan (PAAP)

If objective response is poor or equivocal, discuss adherence, recheck inhaler technique and arrange further tests or consider alternative diagnoses. Usually appropriate to withdraw the treatment.

Low probability

If there is a low probability of asthma and/or an alternative diagnosis is more likely, investigate for the alternative diagnosis. Reconsider asthma if the clinical picture changes or an alternative diagnosis is not confirmed. Undertake or refer for further tests to investigate for a diagnosis of asthma.

Intermediate probability

Adults and children who have some but not all of the typical features of asthma or who do not respond well to initial treatment have an intermediate probability of asthma and require further assessment and diagnosis before a diagnosis can be made. Be aware that some conditions can overlap or mimic asthma, including COPD, obesity, anxiety/panic or dysfunction breathing. Spirometry, with bronchodilator reversibility if appropriate, is the preferred initial test for investigating intermediate probability of asthma in adults and in children old enough to produce reliable results.

Consider referral for tests not available in primary care:

- When the diagnosis is unclear

- Suspected occupational asthma

- Poor response to asthma treatment

- Severe/life-threatening asthma attack

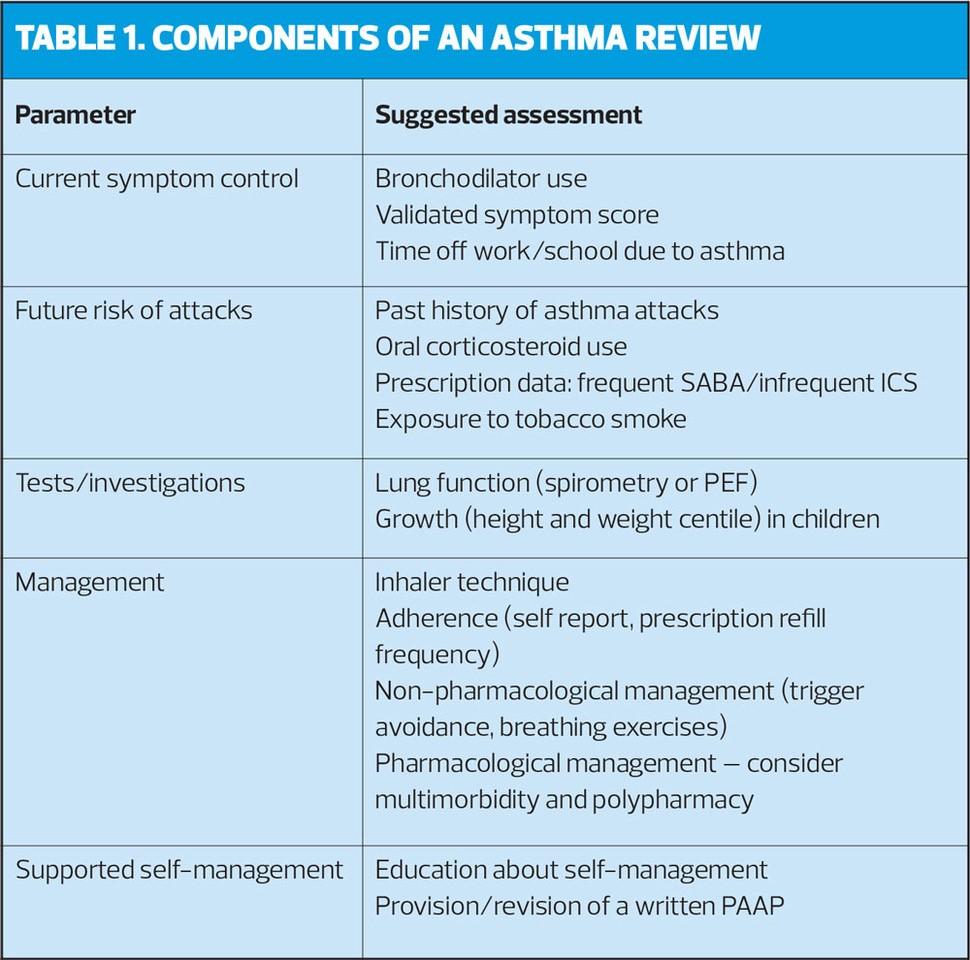

ASTHMA REVIEW

The core components of an asthma review that should be assessed and recorded at least annually are current symptoms, future risk of attacks, management strategies, supported self management and growth in children (Table 1).

Identifying people with poor symptom control and at future risk of asthma attacks enables targeting of care for the individual patient, by:

- Increasing frequency of review

- Commencing/increasing prevent medication

- Personalisation of an asthma plan

- Avoiding triggers such as smoking

- Shifting the balance of necessity/concerns for ICS treatment

When assessing asthma symptoms, a general question such as ‘how is your asthma today?’ is likely to result in a non-specific answer such as ‘I’m OK’.

Ask specific questions about reliever use or such as the Royal College of Physicians ‘3 Questions’.

In the last month:

- Have you had difficulty sleeping because of your asthma symptoms (including cough)?

- Have you had your usual asthma symptoms during the day (cough, wheeze, chest tightness or breathlessness)?

- Has your asthma interfered with your usual activities (e.g. work/housework/school)?

Positive responses should prompt further assessment of symptom control.

The routine use of FeNO testing to monitor asthma is not recommended, except in specialist asthma clinics.

Predicting future risk of asthma attacks

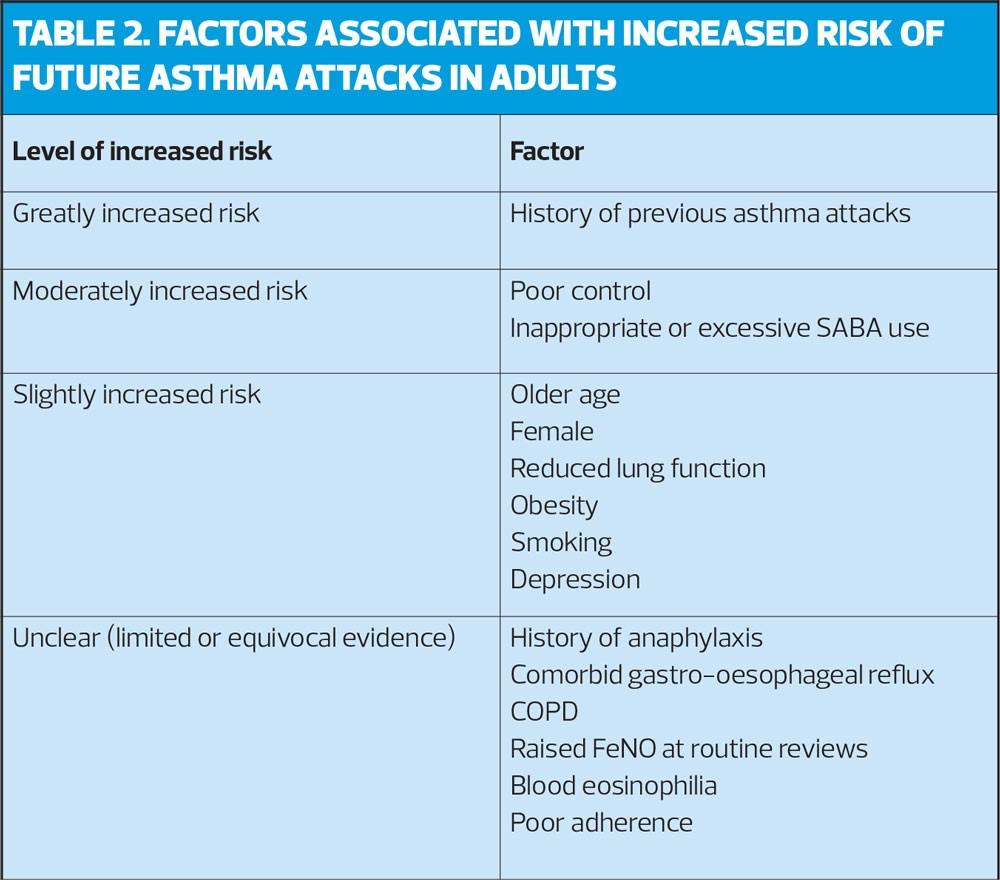

Factors associated with an increased risk of an asthma attack are shown in Table 2.

In people with severe asthma, assess the risk of future asthma attacks at each visit by asking structured questions about asthma control, reviewing history of previous attacks and measuring lung function.

INCREASING ICS TO AVERT AN ASTHMA ATTACK

Regular daily use of preventer medication is the best means of avoiding asthma attacks and the need for increased (rescue) doses of ICS. PAAPs routinely include advice to increase the dose of ICS at the start of an asthma attack in an attempt to abort the attack. The evidence suggests that quadrupling the dose of ICS can reduce the number of severe exacerbations, hospitalisations and may reduce the risk of requiring oral steroids.

In highly adherent patients, or those already on high dose ICS there may be little to gain by increasing ICS. However, using a single combination inhaler for maintenance and reliever therapy (MART) ensures an increased dose of ICS is delivered as the use of formoterol reliever treatment is increased. For people on fixed-dose combination inhalers, increasing the dose of ICS may best be achieved by adding a single ICS inhaler.

Recommendation

In personalised asthma action plans for adults, consider advising quadrupling ICS at the onset of an asthma attack and for up to 14 days to reduce the risk of needing oral steroids.

NON-PHARMACOLOGICAL MANAGEMENT

There is a common perception among patients and carers that there are many environmental, dietary and other triggers of asthma, and that avoiding them will improve asthma and reduce the need for drug therapy. Failure to address these concerns may compromise concordance with recommended pharmacotherapy.

Do’s and don’ts

- Do recommend weight reduction in obese patients to promote general health and reduce respiratory symptoms consistent with asthma. Obese and overweight children should be offered weight-loss programmes to reduce the likelihood of respiratory symptoms suggestive of asthma

- Do advise current and prospective parents of the many adverse effects of smoking on their children, including increased wheezing in infancy and increased risk of persistent asthma

- Do offer appropriate support to stop smoking to people with asthma and parents/carers of children with asthma

- Do administer immunisations as usual, independent of any considerations related to asthma. Response to vaccines may be lessened by high-dose ICS

- Do offer breathing exercise programmes to adults with asthma as an add-on to pharmacological treatment to improve quality of life and reduce symptoms

- Do not offer advice on pet ownership as a strategy for preventing childhood asthma

- Do not routinely recommend physical or chemical methods of reducing house dust mite levels in the home

- Do not recommend air ionisers for the treatment of asthma

INHALER TECHNIQUE AND CHOICE OF DEVICE

- Prescribe inhalers only after patients have received training in the use of the device and have demonstrated satisfactory technique.

- In children aged 5-12 and adults, a pMDI + spacer is as effective as any other hand-held inhaler, but some [adult] patients may prefer some types of DPI.

- The choice of device may be determined by the choice of drug

If the patient is unable to use a device satisfactorily an alternative should be found

- The patient should have their ability to use the prescribed inhaler device (particularly for any change in device) checked by a competent healthcare professional

- The medication needs to be titrated against clinical response to ensure optimum efficacy

- Reassess inhaler technique as part of the structured clinical review

- Generic prescribing of inhalers should be avoided as this might lead to people with asthma being given an unfamiliar inhaler device which they are not able to use properly

- Inhalers with low global-warming potential should be used when they are likely to be equally effective. Where there is no alternative to MDIs, lower volume HFA134a inhalers should be used in preference to large volume or HFA227ea inhalers

- Patients should be encouraged to ask the pharmacy they use if they can recycle their used inhalers.

PHARMACOLOGICAL MANAGEMENT

Before initiating a new drug therapy, practitioners should check adherence with existing therapies and check inhaler technique. See Figure 1 for treatment steps.

SABA

All patients with symptomatic asthma should be prescribed a short-acting β2 agonist (SABA)

Ed: This advice has since been updated. Patients should not be prescribed SABA without also being prescribed ICS

Recommendation

Good asthma control is associated with little or no need for SABA, which should only be used for the relief of symptoms.

Anyone prescribed more than one SABA inhaler device a month* should be identified, have their asthma assessed urgently, and measures take to improve asthma control if this is poor.

*See above

ICS

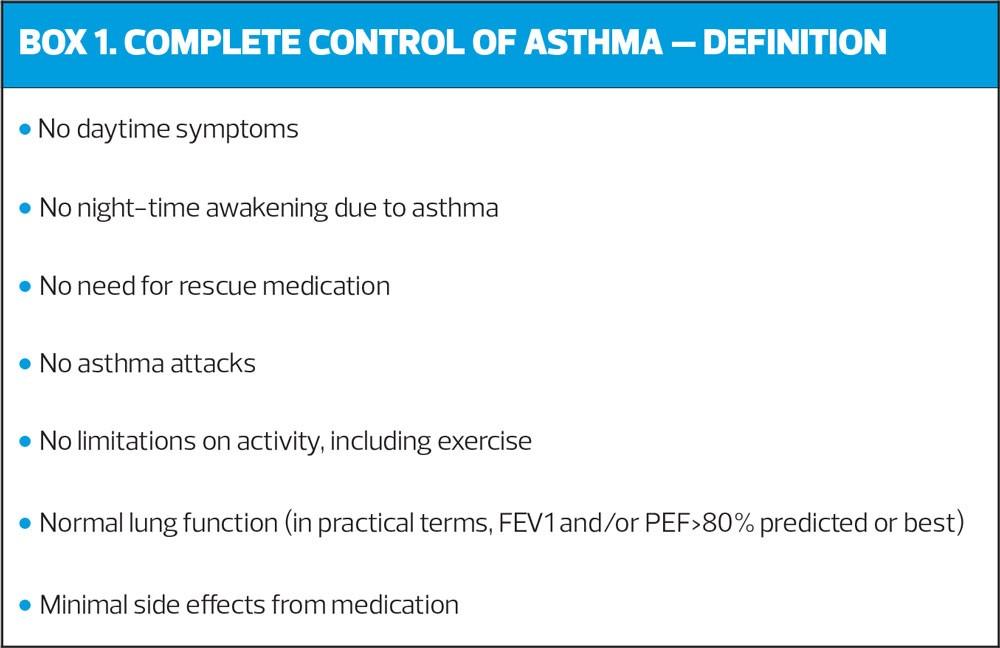

Inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) are the recommended preventer drug for adults and children for achieving overall treatment goals (Box 1).

ICS should be considered for adults, children aged 5-12 and children under the age of 5 with any of the following features:

- Using SABA more than three times a week

- Symptomatic three time a week or more

- Waking one night a week

In addition, ICS should be considered in adults and children aged 5-12 who have had an asthma attack requiring oral corticosteroids in the last two years.

Start patients at a dose of ICS appropriate to severity of disease, usually low dose for adults and very low dose for children (refer to summary of product characteristics for individual product). Titrate the dose to the lowest at which effective control of asthma is maintained.

Recommendation

High dose ICS should only be used after referring the patient to specialist care

Most current ICS are slightly more effective when taken twice rather than once daily. Once daily ICS may be used in patients with milder disease and good or complete control of their asthma. Higher doses of ICS may be needed in patients who are smokers or ex-smokers.

There are alternative preventer therapies but these are less effective than ICS.

- Leukotriene receptor antagonists (LTRA) – some beneficial clinical effect. May be used in children under 5 years who are unable to take ICS

- Sodium cromoglicate and nedocromil sodium – of some benefit in adults and effective in children aged 5-12

- Theophyllines – some beneficial effect

- Antihistamines and ketotifen – ineffective

Initial add-on therapy

Some patients with asthma may not be adequately controlled with low-dose ICS.

Recommendation

The first choice as add-on therapy to ICS in adults is an inhaled long-acting β2 agonist (LABA), which should be considered before increasing the dose of ICS

In children aged 5 and over, an inhaled LABA or an LTRA can be considered as initial add-on therapy

Combination inhalers are recommended to guarantee that the LABA is not taken without ICS, and to improve inhaler adherence.

MART

The use of a single combination inhaler for maintenance and reliever therapy (MART) is an alternative approach to the introduction of a fixed-dose twice-daily combination inhaler. It relies on the rapid onset of reliever effect with formoterol, and by including a dose of ICS ensures that as the need for a reliever increases, the dose of preventer medication is also increased. (A PAAP must be provided with a MART regime).

Additional controller therapies

If control remains poor on low-dose (adults) or very low-dose (children) ICS plus LABA:

- Re-check diagnosis

- Assess adherence to existing medication

- Check inhaler technique.

If more intense treatment is appropriate, consider:

- Increasing dose of ICS to medium (adults) or low (children 5-12 years). If no improvement when LABA is added consider stopping LABA before increasing dose of ICS

- Consider adding an LTRA

- The addition of a long-acting muscarinic antagonist (LAMA) to ICS plus LABA may confer some additional benefit although results of clinical trials are currently inconclusive.

- Theophyllines may improve lung function and symptoms but are associated with an increase in adverse events.

- All patients whose asthma is not adequately controlled on recommended initial controller therapies should be referred for specialist care

DECREASING TREATMENT

Once asthma is controlled, decreasing treatment is recommended but not often done, leaving some patients overtreated.

Recommendation

In adults who are stable on high-dose ICS it is reasonable to attempt to halve the dose of ICS every three months. Some children with milder asthma and a clear seasonal pattern to their symptoms may have a more rapid dose reduction during their ‘good’ season.

- Regular review as treatment is decreased is important. When deciding which drug to decrease first and at what rate, consider the severity of asthma, side effects of treatment, time on current dose, benefits achieved and patient preference

- Patients should be maintained at the lowest possible dose of ICS. Reduction in dose should be slow, and considered every three months, decreasing the dose by 25-50% each time.

See also NICE: the final joint guidance on asthma. Practice Nurse November 2024

Reference

British Thoracic Society/Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network, 24 July 2019 (SIGN 158)

Related guidelines

View all Guidelines