Allergic rhinitis, BSACI 2017

The British Society for Allergy and Clinical Immunology (BSACI) guidelines for the treatment of allergic rhinitis recommend the use of combination intranasal steroids and antihistamines for optimum relief of symptoms.

The revised BSACI guideline stresses the link between allergic rhinitis and the risk of developing asthma, as well as the potential for concurrent rhinitis to worsen asthma control.

Allergic rhinitis (AR) is the most common immunological disease but is often under-diagnosed and poorly managed. This matters because AR significantly reduces quality of life and interferes with attendance at school and work. Symptoms can affect the eyes, sinuses, middle ear, nasopharynx and lower airways. Both AR and non-allergic rhinitis are risk factors for developing asthma. Rhinitis also impairs asthma control, and increases the costs of asthma treatment.

In the UK, the prevalence of rhinitis is 10% in children aged 6-7, 15% in 13-14 year olds, and 26% in young adults. It is more likely to affect boys before adolescence, but in older age groups, women are more likely to be affected. Rhinitis is strongly associated with asthma: 74-81% of people with asthma also have symptoms of rhinitis, and poor control of rhinitis is a risk factor for asthma exacerbations.

The term non-allergic rhinitis (NAR) describes the group of patients with symptoms of rhinitis but without any identifiable allergic triggers.

Occupational rhinitis can be either allergic or non-allergic, and refers to people with pre-existing rhinitis whose symptoms are exacerbated by workplace exposures. More than 300 agents that can cause symptoms have been identified, the same as those that induce occupational asthma (OA), and include protein allergens from animals or plants, e.g. flour, latex, and irritants such as chlorine and ammonia. However, occupational rhinitis is three times more common than OA. Avoidance of exposure is important to prevent progression to OA.

DIAGNOSIS

- A detailed history is needed, covering seasonality (pollen, moulds); indoor or outdoor symptoms (dust mite, household pets), work location and whether there is improvement during holidays, and relationship to potential triggers

- Signs: nasal discharge

– Clear – infection is unlikely

– Unilateral – uncommon (exclude cerebrospinal fluid leak)

– Coloured

1. Yellow indicates allergy or infection; green usually indicates infection.

2. Unilateral – tumour, foreign body, nose picking, misapplication of nasal spray

3. Bilateral - misapplication of nasal spray, granulomatous disorder, predisposition to bleeding disorders, infection, nose picking

- Family history – AR more likely when rhinitis is seasonal or where there is a family history of AR.

- Social history – contact with pets or other animals, occupation

- Medication history – drugs such as alpha- and beta-blockers, aspirin, NSAIDs, oral contraceptives, and topical drugs that affect the sympathetic nervous system can aggravate symptoms; previous treatments for rhinitis – how effective were they, how used and for how long

- Signs: nasal crusting

– Severe crusting is unusual in rhinitis and requires further investigation. Consider chronic rhinosinusitis, nose picking, cocaine abuse, non-invasive ventilation. Topical steroids rarely cause crusting.

- Eye symptoms – include itching, redness, swelling of the white of the eye or eyelid, watering, and (rarely) periorbital oedema

- Lower respiratory tract symptoms – cough, wheeze, shortness of breath

- Other symptoms

– Snoring, sleep problems, sniffing, nasal intonation

– Pollen-food syndrome (triggered by antigens in some fruits, vegetables and nuts)

– Nasal hyper-reactivity

EXAMINATION

- Visual assessment

– Chronic mouth breathing

– Nasal airflow (e.g. metal spatula misting in young children)

- Anterior rhinoscopy

– Appearance may be normal in AR

– Presence of clear, coloured or purulent secretions

– Presence or absence of nasal polyps

INVESTIGATIONS

- Skin prick tests (STP) should be carried out routinely to determine if rhinitis is allergic or non-allergic. High negative predictive value, and should be interpreted in the context of the history

- Serum-specific IgE may be requested if SPT plus clinical history give equivocal results but STP more sensitive to inhaled allergens such as cat dander, mould and grass pollen

- Laboratory tests usually unnecessary but may include full blood count and differential white cell count, C-reactive protein, immunological profile, microbiological examination of sputum and sinus swabs when chronic infection is suspected

- FeNO (fractional exhaled nitric oxide) can be useful to rule out asthma. Normal levels are less than 20 parts per billion

- Measurements of lung function

WHEN TO REFER

- Patients with unilateral symptoms, heavily blood-stained discharge or pain should be referred to ENT

- Patients with nasal blockage not relieved by pharmacotherapy, or structural abnormalities should be seen by a surgeon

TREATMENT

- Allergen avoidance – clearly effective in seasonal AR (hayfever) but difficult for patients with house dust mite allergy as it is difficult to reduce exposure to mites in the home. Interventions that may be helpful include wearing sunglasses during pollen season, applying balms e.g. Vaseline to the nose. Patients with allergy to pets such as cats, dogs, or horses should be advised to avoid these animals, but may choose to continue to keep them . There is little evidence for use of HEPA filters or temperature controlled laminar airflow treatment in rhinitis.

- Saline irrigation has a small beneficial effect on reducing symptoms.

- A 10-second burst of carbon dioxide from a pressurised container into the nasal airway, with the mouth open, reduces all symptoms of rhinitis within minutes. It is available over the counter for rescue treatment (Serenz).

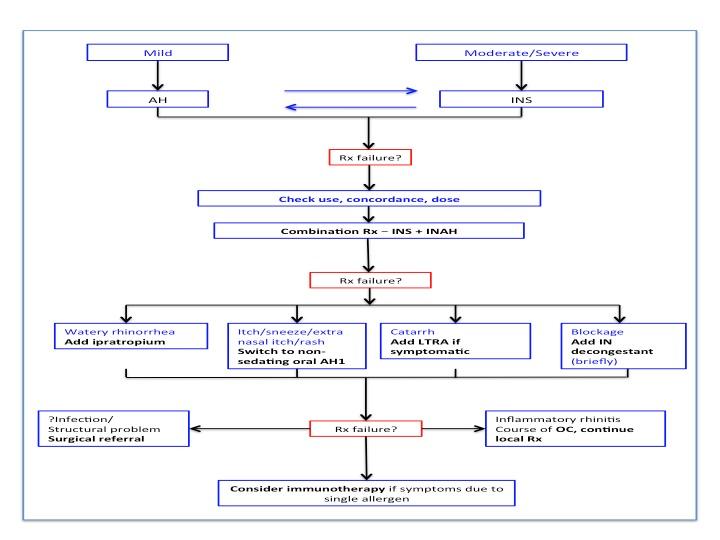

PHARMACOTHERAPY

- Antihistamines – available as oral, intranasal and ocular preparations. All effective, but it is important to use a drug with the least side effects and which is suitable for the patient at the time (i.e. during pregnancy, breastfeeding)

– First generation oral antihistamines are not recommended because of their sedative and cognitive effects, which can impair driving and examination results already affected by rhinitis symptoms. Antihistamines with an anticholinergic effect are associated with the development of dementia.

– Second generation antihistamines have been associated with cardiac arrhythmias and should be used with caution in those with cardiac risk factors

- Topical antihistamines

– Nasal (topical H1-antihistamine) – superior to oral antihistamines in relieving symptoms and with faster onset of action. Continuous treatment is more effective than on demand use. Less effective than intranasal steroids in AR. Use first line in mild-to-moderate intermittent and mild persistent rhinitis

- Corticosteroid therapy

– Intranasal corticosteroids (INS) reduce all symptoms of AR. Systemic absorption is negligible with mometasone fuorate, fluticasone furoate and fluticasone propionate, and one of these should be used for children. Systemic absorption is modest for other INS, and high for betamethasone, which should only be used short-term. Side effects may include nasal irritation, sore throat and nose bleeds (10% of users). Correct use is important to reduce local adverse effects. Use first line for moderate-to-severe persistent symptoms.

– Oral steroids or steroid drops should be used for severe nasal obstruction, initially for up to one week.

- Combination therapy

– INS and topical H1-antihistamine combination (currently available as a combination spray containing axelastine and fluticasone propionate, Dymista) leads to greater symptom improvement than using either agent alone in severe AR. Use in patient with symptoms that remain uncontrolled with antihistamine or INS monotherapy

Complementary therapies

- There is inadequate evidence for the use of all complementary therapies, including acupuncture, herbal medicines and homeopathy, and they are not recommended for clinical use

SEVERE NASAL OBSTRUCTION

- Oral steroids can be used as short term rescue therapy during severe exacerbations despite compliance with conventional pharmacotherapy

- Intranasal decongestants – topical formulations allow relief of nasal congestion with minutes. However, only short-term use (generally less than 10 days) is recommended as paradoxical increase in nasal congestion may occur, with the risk increasing with duration of use.

OCULAR THERAPY

- Sunglasses reduce eye symptoms but complete protection is not possible. Ocular symptoms can be suppressed by oral antihistamines, and by intranasal agents including corticosteroids, antihistamines and combination preparations.

- Ocular symptoms are often better treated with topical eye drops: mast cell stabilisers such as sodium cromoglycate, nedocromil sodium and lodoxamine are generally effective. A drug with both mast cell stabilising and antihistaminic properties, olopatadine is often effective and well tolerated – its twice daily application makes it suitable for contact lens wearers. Topical steroids are effective but can be sight-threatening (ocular hypertension/glaucoma, cataract and infection).

IMMUNOTHERPAY

- Allergen immunotherapy can improve symptoms, reduce medication requirements and improve quality of life

- Subcutaneous injection immunotherapy (SCIT) is effective for seasonal rhinitis due to pollens and perennial rhinitis due to house dust mite. SCIT requires weekly up-dosing injections followed by maintenance injections every 4-6 weeks for 3-5 years. It should only be given in specialist clinics

- Sublingual immunotherapy (SLIT) is a relatively new, safe and effective alternative treatment for AR due to grass pollen, ragweed and house dust mite. It is well tolerated with mainly local side effects. After supervision of the first dose by the prescriber, it is self-administered at home.

- The choice of SCIT or SLIT depends on patient preference as there are no adequately powered head-to-head comparative trials

- Allergen immunotherapy is recommended for patients with objective confirmation of IgE sensitivity for patients with seasonal rhinitis whose symptoms persist despite maximal drug therapy, and perennial AR with an allergy to house dust mites (who do not respond adequately to anti-allergic drugs and where the allergen cannot easily be avoided.

RHINITIS IN CHILDREN

Acute viral rhinitis is common, peaks in winter, and frequency of episodes varies with age, birth order and degree of day-care exposure: between 1 and 10 episodes a year is usual, with a peak between 6 months and 6 years, after that, 1–2 episodes a year, usually in winter is ‘normal’.

Other causes of symptoms include retained foreign body, nasal septum deviation, nasal polyps and cerebrospinal fluid leak.

AR affects 3% of 4-year-olds, and is a risk factor for developing asthma. It often presents alongside other atopic conditions such as asthma, eczema and food allergy.

The approach to diagnosis is the same as for adults.

Therapy is based on the same principles as for adults, but monitor growth especially if children are receiving steroids by multiple routes.

Otitis media with effusion and/or adenoidal hypertrophy may be associated with AR, and treatment for rhinitis may be helpful.

RHINITIS IN PREGNANCY AND BREASTFEEDING

Rhinitis affects 20% of pregnancies. Causes are multifactorial but may include nasal vascular engorgement and placental growth hormone. Rhinitis in pregnancy may not be adequately treated during routine antenatal care, but can have a negative impact on quality of life. Women with pre-existing rhinitis are likely to be most severely affected.

During pregnancy, most medications cross the placenta and should only be prescribed when the benefits outweigh risks.

- Nasal lavage is safe and effective and reduce the need for antihistamines

- Chromones have not been shown to affect the fetus and are the safest drug for use in the first trimester

- The safety of INS in pregnancy has not been established but systemic absorption is minimal. Beclomethasone, fluticasone propionate and budesonide are widely used is pregnant women with asthma.

- Decongestants should be avoided

- Patients on immunotherapy (who will be under specialist care) can continue treatment during pregnancy, but treatment should not be initiated

Similar recommendations apply during breastfeeding: avoid antihistamines as they are excreted in breastmilk, and may cause drowsiness in the infant and poor feeding. As in pregnancy, pharmacotherapy should only be used when the potential benefits outweigh risks. The lowest dose of any drug therapy should be used for the shortest duration.

Reference

1. BSACI guideline for the diagnosis and management of allergic and non-allergic rhinitis, 2017. Clinical & Experimental Allergy 2017;47(7): 856-889

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/cea.12953

Related guidelines

View all Guidelines