Best practice in oral contraception

AMY SHIRTLIFF BA(Hons), MSC, RGN; Nurse practitioner & writer

Practice Nurse 2025;55(4):26-30

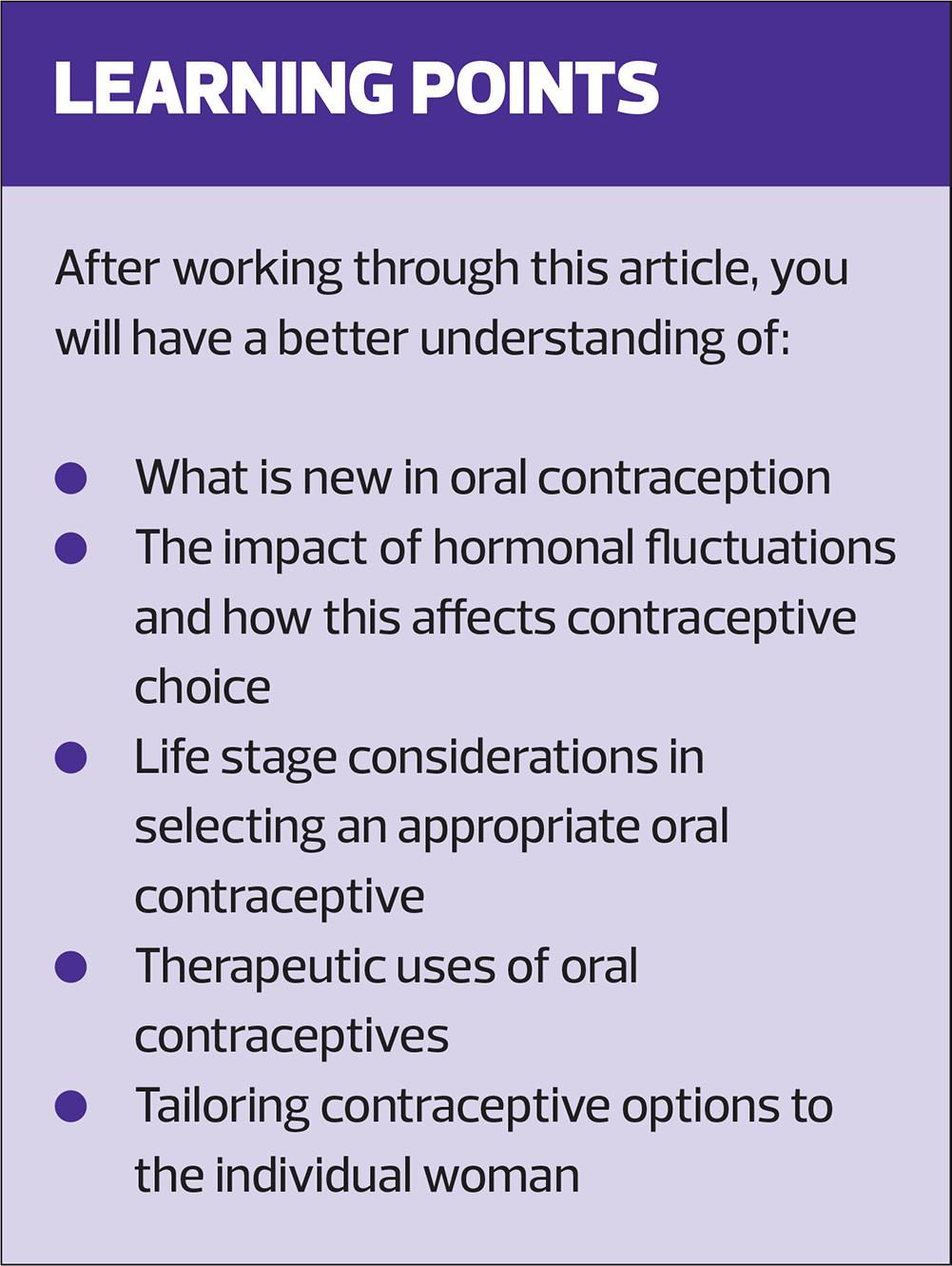

With newer pill options and ever-evolving evidence, this article provides both a refresher on best practice and a timely update, helping clinicians confidently navigate oral contraception in 2025.

Oral contraception remains a cornerstone of primary care, offering modifiable, individualised options with therapeutic progestins and the benefits of oestrogen.1

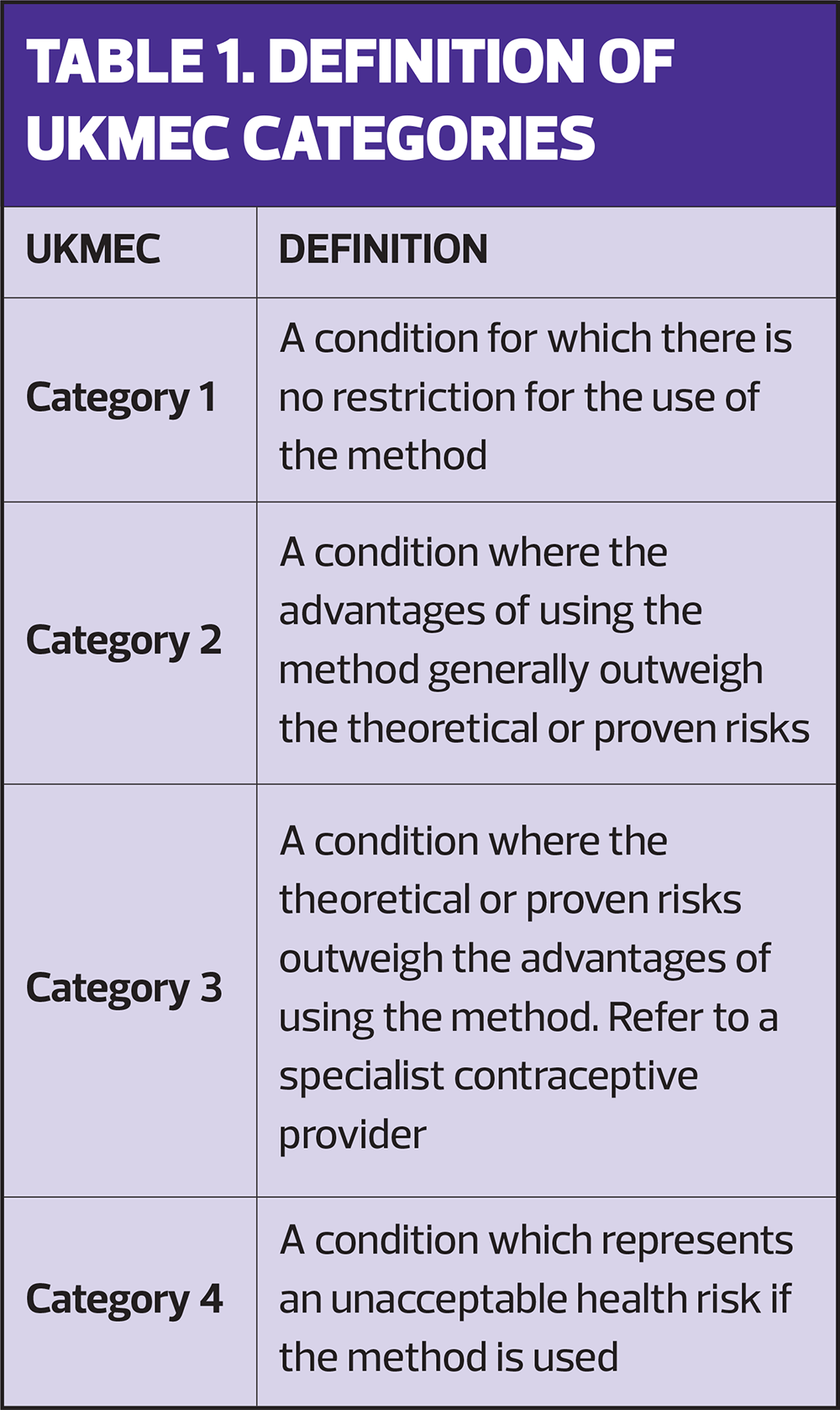

Effective contraceptive care begins with understanding the patient’s needs, lifestyle, and symptom patterns, moving beyond a simple checklist. Once this foundation is laid, use UKMEC guidance to carry out a thorough risk assessment, including blood pressure, BMI, and family and medical history.2 Review past experiences: what worked, what didn’t, and what assumptions might still influence choices. After establishing oestrogen suitability, explore therapeutic needs in depth.3 Clinicians must ask the right questions rather than expect patients to volunteer details. Only after gathering all these details can the most suitable pill be considered.4

Women experience various hormonal symptoms due to fluctuating oestrogen, progestogen, and androgen levels:

Oestrogen fluctuations: Sudden drops (early follicular/premenstrual phases) can cause low mood, irritability, fatigue, headaches, poor concentration.

High oestrogen (late follicular/ovulatory phase) may cause breast tenderness, anxiety, or migraines in some women but can improve mood and mental clarity in others.5

Sustained low oestrogen (e.g. perimenopause, PCOS, thyroid disorders, eating disorder history, excessive exercise, chemo/radiotherapy6) may cause vaginal dryness, low libido, dry skin, adverse mood and cognitive changes.

Progesterone fluctuations (post-ovulation rise/premenstrual drop) are associated with fatigue, low mood, increased appetite, and mood instability.

Low progesterone can contribute to breakthrough bleedingandpremenstrual mood symptoms.

Androgens can lead to acne, oily skin, hirsutism, and hair thinning.

Low androgens rarely cause symptoms but may reduce libido and muscle mass.5

Oral contraceptive effects vary widely based on oestrogen dose and type, and progestin type. Combined pills (COCPs) contain synthetic ethinylestradiol or natural oestrogens (estradiol valerate, estradiol hemihydrate, estetrol). Progestins fall into four generations, differing by chemical structure and side effect profiles: first (norethindrone, norethisterone), second (levonorgestrel), third (desogestrel, gestodene), and fourth/’newer’ (drospirenone, dienogest, nomegestrol). Progestin choice is critical, as it dictates androgenic or antiandrogenic effects, allowing therapeutic tailoring.2

A table comparing progestins’ androgenic and antiandrogenic properties can be found at: https://www.nhstaysideadtc.scot.nhs.uk/approved/guidance/NHS%20Tayside%20Hormonal%20Contraception%20Guide.pdf .7

Oestrogen

The oestrogen in COCPs suppresses endogenous oestrogen production via hypothalamic–pituitary axis feedback, reducing natural, and often symptom causing hormonal fluctuations.2 In women with lower baseline oestrogen levels, COCPs provide exogenous oestrogen to prevent deficiency symptoms.8 In those with strong endogenous ovarian activity, COCPs suppress cyclical peaks causing symptoms, while delivering a consistent exogenous dose.

It is a misconception that oestrogen inherently causes side effects; most issues stem from dose issues or individual sensitivity. While oestrogen dose may need adjusting either way, it's more common to increase from 20 mcg to 30 mcg due to breakthrough bleeding and poor cycle control, whereas decreasing from 30–35 mcg is considered if oestrogenic symptoms occur or worsen.9 Oestrogen use also provides health benefits, including lighter periods, less menstrual pain, reduced acne, less PMS, improved bone health, and lower risks of endometrial, ovarian, and colorectal cancers. For those without contraindications, a low, tailored dose of oestrogen may offer better symptom management alongside effective contraception.2

Progestins

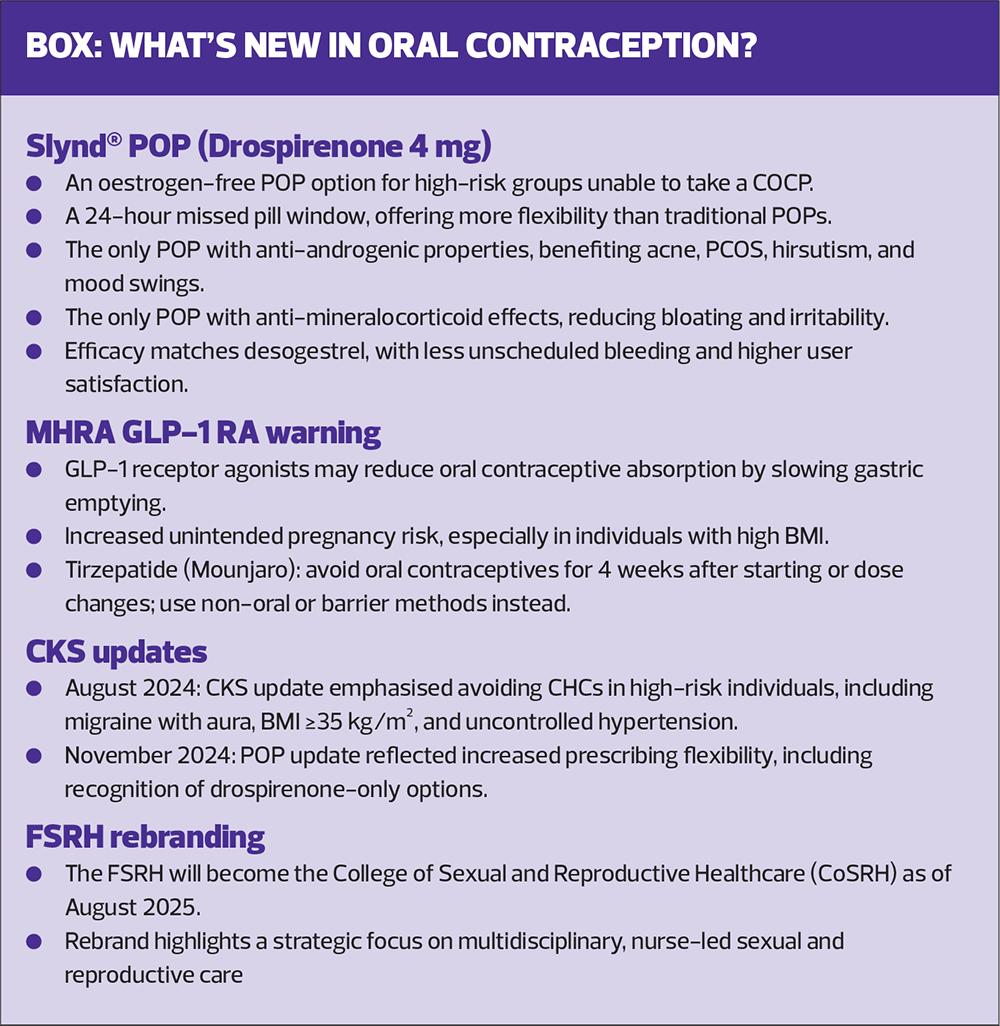

Progestins in COCPs and progestogen-only pills (POPs) primarily thicken cervical mucus to prevent sperm penetration, and some also suppress ovulation (desogestrel and drospirenone).10 Progestin choice in both COCPs and POPs is crucial, especially when oestrogen is contraindicated. While oestrogen can offset some progestin-related effects, it doesn’t do so entirely. Although levonorgestrel-containing COCPs remain preferred by local formularies due to slightly lower venous thromboembolism (VTE) risk, the majority of women find antiandrogenic options more helpful overall.11 Until recently, all POPs contained androgenic progestins, limiting options for those unable to take oestrogen but still needing symptom control. The drospirenone-only POP (Slynd) provides an antiandrogenic alternative.12

Mood is influenced by both progestin type and oestrogen presence: exogenous oestrogen suppresses mood-fluctuating hormones, and COCPs with newer generation progestins often link to more stable mood.13,14 For women experiencing side effects despite switching progestins, particularly after trying a COCP containing drospireone, combined pills containing naturally derived estradiol (Qlaira, Zoely, Drovelis) may be preferred.14

Clinicians must consider POPs carefully in women with a history of depression: multiple sources link them to worsening mental health symptoms and advise they be used ‘with caution’.15 Evidence suggests earlier generation progestins (1st–3rd) may affect mood more, though links to androgenicity remain unclear. Desogestrel has been associated with worsened mood, irritability, and depressive symptoms,16 while emerging evidence indicates drospirenone-only POPs may cause fewer mood-related effects. One large observational study found increased antidepressant use among POP users, particularly adolescents, and a study in postpartum women using drospirenone-only POPs showed significant reductions in Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale scores.17 Although the Faculty of Sexual & Reproductive Healthcare (FRSH) issued a response to the above study,18 further research has since supported associations between POPs and androgenic COCPs and depression in susceptible women. This potential risk must be taken seriously and weighed carefully when advising on the most suitable options.

Patients’ medical backgrounds and risk factors must also be carefully considered. However, while the differences in VTE risk between different progestins in combination with oestrogen in COCPs is notable, the absolute risk remains small; even the highest risk (3rd generation progestins and drospirenone) is no higher than 0.12%,2 and evidence of cardiovascular risk is mixed, with studies suggesting that available COCPs do not increase the risk of myocardial infarction or stroke in healthy non-smoking women of any age.19 As the types of estradiol in naturally derived pills (Qlaira, Zoely, and Drovelis) have less impact on liver protein synthesis, evidence now shows they have a lower risk of VTE.20

NICE guidance states that while typical first line options are 30mcg ethinylestradiol plus norethisterone or levonorgestrel, consider the woman's preference, as any COCP can be offered first-line.2,21 NICE guidelines also state that any POP can be started first line and patient choice should be considered.22

POPs are recommended for women with oestrogen contraindications or significant oestrogen-related side effects. However, it is important to note that POPs may allow ongoing fluctuations in ovarian oestrogen, worsening symptoms like mood changes, acne, or headaches in some individuals.2 For those who benefit from oestrogen’s stabilising effects, its removal can worsen hormone-responsive symptoms.

This was highlighted during the COVID-19 pandemic, when many women already taking the COCP were told POPs were the only option due to lower risk and ease of remote prescribing. While appropriate for some, this often occurred without fully considering symptom control or patient preference. One study found nearly 50% of participants were seeking a continuation or repeat COCP prescription, and 41% had difficulty accessing their preferred method. Despite longstanding NICE guidance recommending a 12-month COCP prescription after 3 months’ use,21 many women struggled unnecessarily.23

Clinicians must meticulously consider each woman’s symptoms and history when selecting contraception. Educating patients about risks and encouraging them to report medical changes is vital. A 3-month adjustment period should be advised when starting or changing pills, but when side effects and hormonal symptoms are involved, that’s a long time to feel unwell. If you’re asking a woman to commit to a pill 3 months, ensure it’s the best therapeutic option for her.24

The pill check

A pill check shouldn’t be rushed. Clinicians must review risk factors and confirm there are no new contraindications. It’s important to assess adherence and whether the patient understands missed pill rules. Open-ended questions help uncover subtle, often unreported side effects. If the patient is unhappy, revisit the initial consultation advice.

Both FRSH and NICE guidance support prescribing a 12-month supply of both COCPs and POPs to reduce gaps in use and unintended pregnancy.21 This annual review may be undertaken remotely with the provision of blood pressure and weight from the patient for COCPs, and a ‘face-to-face review is not necessary for safe prescribing’.2 Interim reviews are necessary in the event of significant diagnoses or unwanted side effects. When switching contraceptive methods it’s essential to avoid any lapse in protection.2 Most hormonal methods should begin immediately after the last active pill of the previous pack, though specific timing can vary.2,20Simple strategies such as setting alarms, using apps, and linking pill-taking to routines can improve adherence.25 Asking how patients remember their pill is often more revealing than yes/no questions.

LIFE STAGE CONSIDERATIONS

Adolescents

COCPs can regulate cycles and improve acne, but progestogen-only options matter when oestrogen is contraindicated. Confidentiality and autonomy are essential. Under-16s can consent if Gillick competent. Unhurried, non-judgmental discussions are key. Though LARCs are often preferred for reliability, pills may feel less intimidating and offer greater control.2

Postpartum

POPs can be started immediately after childbirth, regardless of breastfeeding. They do not affect milk supply or increase VTE risk. COCPs are contraindicated (UKMEC 4) during the first 6 weeks postpartum for breastfeeding individuals due to VTE risk and possible milk supply effects. After 6 weeks, if fully breastfeeding, COCP changes to UKMEC 3, and by 6 months postpartum or with reduced breastfeeding, it becomes UKMEC 2. For non-breastfeeding individuals, COCP is UKMEC 3 in the first 3 weeks postpartum due to high VTE risk, then UKMEC 2 from 3 to 6 weeks if no other risk factors exist (See Table 1). Many clinicians delay COCP initiation until after 6 weeks to simplify risk assessment and align with the postnatal check.3,10

Age 40 onwards

Background risks increase, therefore guidance changes slightly. COCPs continue to remain suitable for healthy, low-risk, and no method is contraindicated by age alone for women in their 40s.3,26Oestrogen continues to provide key benefits, including managing perimenopausal symptoms, regulating bleeding, and preserving bone density.27,28 For contraindications such as migraine with aura or VTE history, progestogen-only methods are necessary. Transitioning off COCPs around 50 often simplifies menopause management, as COCPs suppress follicle stimulating hormone (FSH) and can mask menopause onset.3,26

THERAPEUTIC USES OF ORAL CONTRACEPTIVES

The following therapeutic uses primarily apply to COCs, as evidence is strongest for combined formulations.

Acne: COCPs increase sex hormone-binding globulin, reducing free testosterone and improving inflammatory and non-inflammatory acne lesions. NICE recommends COCPs as first-line treatment when appropriate.19

Polycystic Ovary Syndrome (PCOS): For patients not seeking pregnancy, COCPs regulate cycles and suppress ovarian androgen production, improving hirsutism and acne. Essential metabolic monitoring is required due to insulin resistance risks.19

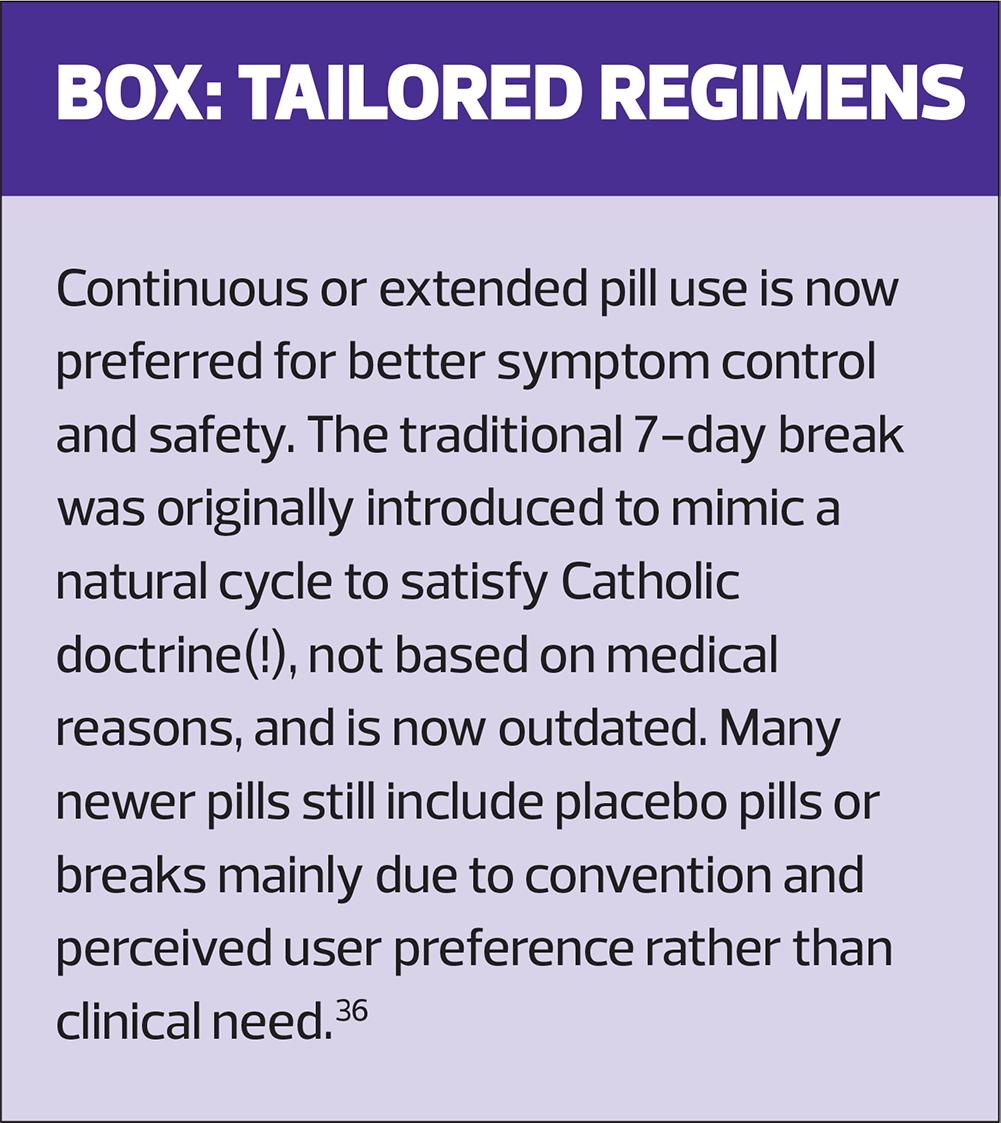

Premenstrual Dysphoric Disorder (PMDD): Extended or continuous COCP regimens, especially with drospirenone and other fourth generation COCPs can reduce cyclical mood symptoms.19

Dysmenorrhoea: COCPs reduce uterine contractility and menstrual pain by lowering prostaglandin synthesis. Continuous regimens often provide better symptom relief than cyclic use.19

Heavy Menstrual Bleeding (HMB): COCPs suppress ovulation and stabilise the endometrium, reducing menstrual volume and duration. Qlaira is a first-line treatments alongside tranexamic acid, tailored to patient preference.2

Endometriosis and Adenomyosis: Continuous or extended COCP use suppresses menstruation and hormonal stimulation of ectopic endometrial tissue in endometriosis and stabilises the endometrium in adenomyosis, reducing pelvic pain and dysmenorrhoea.2

Functional Ovarian Cysts: COCPs prevent new follicular or corpus luteum cysts by suppressing ovulation but do not speed resolution of existing cysts.29

Endometrial Protection in Chronic Anovulation: COCPs provide progestogenic opposition to unopposed oestrogen, reducing endometrial hyperplasia risk in chronic anovulation conditions like PCOS, hypothalamic dysfunction, and perimenopause.29

Primary Ovarian Insufficiency (POI) and Hypogonadism: In adolescents and young adults, COCPs support hormone replacement and protect the endometrium.30

DOCUMENTATION AND SAFETY NETTING

Say it, then write it

A safe contraception consultation follows a clear sequence: provide the patient with necessary information, then document it. This includes discussing side effects, UKMEC eligibility, missed pill rules, STI risk, and what to expect. Document not just what you said, but what the patient understood.

Rationale requires detail

Record why the method was chosen, alternatives discussed, comorbidities, and UKMEC category. ‘Discussed risks’ isn’t enough. Clear notes protect both patient and clinician if adverse effects arise later.31

Safety net properly

Replace vague advice (‘call if you have problems’) with specific red-flag symptoms and follow-up instructions to meet professional standards. Proper documentation reduces risk and lowers complaints.32

Back up verbal advice with leaflets or trusted links, as patients forget 40–80% of medical information and often misremember the rest!33

ADDRESSING INEQUALITIES AND IMPROVING ACCESS

Discrimination has no place in contraceptive care, where trust and dignity are essential. Healthcare professionals must actively educate themselves on patients' diverse realities to provide validating care. Systemic bias and cultural insensitivity disproportionately affect ethnic minorities, people with disabilities, LGBTQ+ individuals, and those facing socioeconomic deprivation.34 The Candidacy Framework in a recent British Journal of General Practice article explains how perceptions of care and clinical judgement are disrupted by discrimination. Addressing these structural issues requires intentional, data-led service redesign, including equity audits and targeted solutions such as extended hours and multilingual information to make care truly accessible and person-centred.35

CONCLUSION

Oral contraception has evolved into a highly tailored part of therapeutic hormone care. Nurses play a vital role in applying clinical guidelines and communicating knowledge to support informed patient choice. A solid understanding of low-dose oestrogen’s biological role is crucial as a cornerstone of contraception. As the field advances, an informed, equitable, and patient-focused approach remains key to supporting reproductive autonomy for all.

References

1. Women’s health toolkit: Contraception. RCGP Learning https://elearning.rcgp.org.uk/mod/book/view.php?id=12534&chapterid=824

2. Faculty of Sexual & Reproductive Healthcare (FSRH). UK Medical eligibility criteria for contraceptive use (UKMEC); 2019. https://www.fsrh.org/Public/Public/Standards-and-Guidance/uk-medical-eligibility-criteria-for-contraceptive-use-ukmec.aspx

3. FSRH. FSRH Guideline: Combined hormonal contraception; 2023 https://www.fsrh.org/Common/Uploaded%20files/documents/fsrh-guideline-combined-hormonal-contraception-october-2023.pdf

4. Nimbi F, Rossi R, Tripodi F, et al. A Biopsychosocial Model for the Counseling of Hormonal Contraceptives: A Review of the Psychological, Relational, Sexual, and Cultural Elements Involved in the Choice of Contraceptive Method. Sex Med Rev 2019;7(4):587-596.

5. Endocrine Society. Reproductive Hormones; 2022. https://www.endocrine.org/patient-engagement/endocrine-library/hormones-and-endocrine-function/reproductive-hormones

6.Villines Z. What happens when oestrogen levels are low? 2025 https://www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/321064.

7. Tayside Sexual & Reproductive Health Service (TSRHS). NHS Tayside Hormonal Contraception Guide; 2024 https://www.nhstaysideadtc.scot.nhs.uk/approved/guidance/NHS%20Tayside%20Hormonal%20Contraception%20Guide.pdf

8. Baskaran C, Cunningham B, Plessow F et al. Oestrogen replacement improves verbal memory and executive control in oligomenorrheic/amenorrheic athletes in a randomized controlled trial. J Clin Psychiatry. 2017 May;78(5):e490-e497.

9. Gallo MF, Nanda K, Grimes DA et al. 20 µg versus >20 µg oestrogen combined oral contraceptives for contraception. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013 Aug 1;2013(8).

10.Faculty of Sexual & Reproductive Healthcare. FSRH Guideline: Progestogen-only Pills; 2023. https://www.fsrh.org/Common/Uploaded%20files/documents/fsrh-ceu-clinical-guideline-progestogen-only-pills-aug22-amended-11july-2023-.pdf.

11. Sangthawan M, Taneepanichskul S. A comparative study of monophasic oral contraceptives containing either drospirenone 3 mg or levonorgestrel 150 μg on premenstrual symptoms. Contraception 2005; 71(1):1 - 7

12. FSRH. FSRH CEU statement: Drospirenone 4mg progestogen-only Pill (Slynd®️); 2024 https://www.fsrh.org/Common/Uploaded%20files/documents/fsrh-ceu-statement-drsp-pop-janu24.pdf

13. Poromaa IS, Segebladh B. Adverse mood symptoms with oral contraceptives. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 2012; 91:420–427.

14. Robertson E, Thew C, Thomas N, et al. Data on the feasibility and clinical outcomes of a nomegestrol acetate oral contraceptive pill in women with premenstrual dysphoric disorder. Front Endocrinol 2021;12:704488.

15. Mu E, Kulkarni J. Hormonal contraception and mood disorders. Aust Prescr. 2022;45(3):75-79.

16. Watson S, Härmark L. Desogestrel and panic attacks – a new suspected adverse drug reaction reported by patients and health care professionals on spontaneous reports. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2018;84(8):1858-1859.

17. Caruso S, Caruso G, Bruno MT, et al. Effects of drospirenone only pill contraception on postpartum mood disorders: A prospective, comparative pilot study. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2023 Sep;288:73-77.

18. FSRH. CEU response to published study: Association of Hormonal Contraception with Depression; 2016. https://www.fsrh.org/Common/Uploaded%20files/documents/association-of-hc-with-depression.pdf

19. De Leo V, Musacchio M, Cappelli V, et al, Hormonal contraceptives: pharmacology tailored to women's health. Hum Reproduct Update 2016: 22(5):634–646

20. Frisendahl C, Kallner H, Gemzell-Danielsson K. The clinical relevance of having more than one oestrogen in combined hormonal contraception to address the needs of women, Best Pract Res Clinl Obstet Gynaecol 2025; 98:102571.

21.NICE CKS. Combined oral contraceptives; 2024. https://cks.nice.org.uk/topics/contraception-combined-hormonal-methods/management/combined-oral-contraceptive/

22. NICE CKS. Progesterone-only pill; 2024 https://cks.nice.org.uk/topics/contraception-progestogen-only-methods/management/progestogen-only-pill/

23. Ma R, Foley K, Saxena S. Access to and use of contraceptive care during the first COVID-19 lockdown in the UK: a web-based survey Br J Gen Pract Open 2022;6(3):BJGPO.2021.0218

24. Bitzer J, Marin V, Lira J. Contraceptive counselling and care: a personalized interactive approach. Eur J Contracept Reprod Health Care. 2017 Dec;22(6):418-423.

25. Nguyen M, Chan EYL, Nguyen T, et al. Traditional or technological? A cross sectional survey of oral contraceptive reminders in young adults. Sex Reprod Healthc. 2021 Sep;29:100618.

26. FRSH. Contraception for Women Aged Over 40 Years; 2025. https://www.fsrh.org/Common/Uploaded%20files/documents/fsrh-guideline-contraception-for-women-aged-over-40-years.pdf

27. GPnotebook. Contraception in women aged over 40 years; 2024. https://gpnotebook.com/en-GB/pages/gynaecology/contraception-in-women-aged-over-40-years

28. Kim SM, Shin W, Kim HJ, et al. Effects of Combination Oral Contraceptives on Bone Mineral Density and Metabolism in Perimenopausal Korean Women. J Menopausal Med. 2022 Apr;28(1):25-32

29. Cameron S. Contraception and gynaecological care. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol 2009;23(2):211-220

30. Torrealday S, Kodaman P, Pal L. Premature Ovarian Insufficiency - an update on recent advances in understanding and management. F1000Research. 2017;29(6):2069.

31. MDU. Effective record-keeping; 2024. https://www.themdu.com/guidance-and-advice/guides/effective-record-keeping

32. National Institute for Health and Care Research. Safety-netting in general practice: how to manage uncertain diagnoses; 2023. https://evidence.nihr.ac.uk/alert/safety-netting-in-general-practice-manage-uncertain-diagnoses/

33. Kessels RP. Patients' memory for medical information. J R Soc Med. 2003;96(5):219-22.

34. BMA. Anti-discrimination statement; 2024. https://www.bma.org.uk/about-us/equality-diversity-and-inclusion/edi/bma-anti-discrimination-statement-2024

35. Mawson R, Hodges V, Salway S, et al. Understanding access to sexual and reproductive health in general practice using an adapted Candidacy Framework: a systematic review and qualitative evidence synthesis. Br J Gen Pract 2025;BJGP.2024.0522.

36. Walker S. Contraception: the way you take the pill has more to do with the Pope than your health. The Conversation; 2019. https://theconversation.com/contraception-the-way-you-take-the-pill-has-more-to-do-with-the-pope-than-your-health-109392

Related articles

View all Articles