Severe asthma: what do I need to know?

Jayne Longstaff

Jayne Longstaff

RGN BSc

Oaks Healthcare, Waterlooville, Hants

Jessica Gates,

MRCP

Epson and St Hellier NHS Trust

Hitasha Rupani

PhD MRCP

Consultant Respiratory Physician, University Hospital Southampton NHS Foundation Trust

Practice Nurse 2021;51(9):28-34

Specialist assessment of patients with severe asthma can improve outcomes, but it appears that large numbers of people with potential severe asthma are under recognised in primary care and are not being referred appropriately

Asthma is one of the most common respiratory conditions. There are over 5.4 million people with asthma living in the UK,1 and people with asthma face a significant burden of morbidity and impact on their quality of life. Moreover, 1,400 people in the UK die each year from asthma; an exceptionally high toll for a manageable condition.1 The National Review of Asthma Deaths reported that nearly 20% of deaths attributable to asthma in the UK were associated with potentially avoidable factors, such as access to specialist care and delayed referral.2

Review in specialist care involves a systematic assessment and has been shown to improve asthma outcomes, and to reduce exacerbations and oral corticosteroid use.3 However, a recent report suggests that 72% of adults with asthma poorly controlled in primary care had not been referred or had a specialist review in the past year.4

This article discusses the identification and management of patients with potential severe asthma, referral to specialist centres and the role of biological therapies.

WHAT’S IN A DEFINITION?

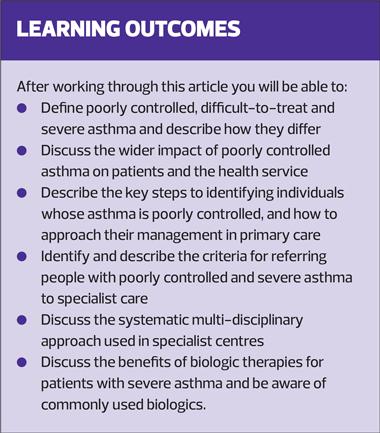

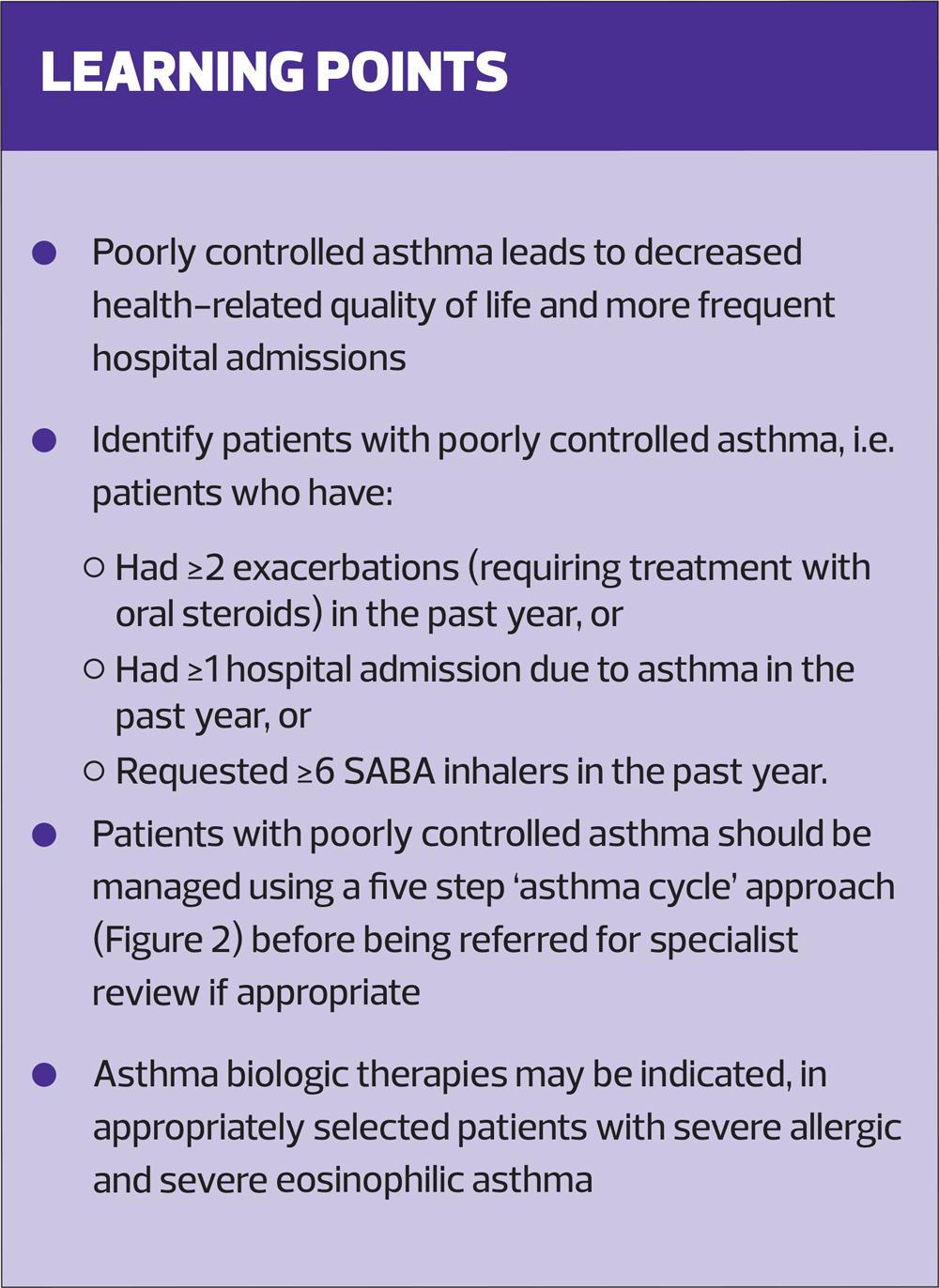

Asthma is often described as poorly controlled, difficult-to-treat or severe (Box 1) and it is important to understand the prevalence of these sub-classifications, and how they differ.

Poorly controlled asthma leads to more days off work, a limitation on daily activities, decreased health-related quality of life and more frequent hospital admissions compared to controlled asthma. Additionally, patients with poorly controlled asthma use more medication, including rescue inhalers and oral corticosteroids (OCS).5

A Dutch population survey has shown that about 17% of adults with asthma have difficult-to-treat asthma and 3.7% have severe asthma.6 If these findings are translated to the UK population this would equate to approximately 850,000 adults with asthma who are on high treatment steps (GINA or BTS) yet have poor symptom control and ongoing exacerbations, with about 200,000 patients having severe asthma. The diagnosis of severe asthma is usually made in specialist severe asthma centres and after the patient has received input from the multi-disciplinary team (MDT) (see below).

Asthma is also often defined as allergic or eosinophilic.

- Allergic asthma is asthma that is triggered by allergens such as pollens, animals, dust mites and moulds. Patients with allergic asthma have raised levels of IgE in their blood and sensitisation to different allergens is confirmed through skin prick testing and/or blood tests.

- Patients with eosinophilic asthma have raised levels of eosinophils in blood (≥ 0.3 x109 cells/L) and sputum.

Since asthma is a variable disease, in addition to reviewing the patient’s current blood eosinophil count (BEC), historical results should also be considered. A review of primary care patient records has shown that about 50% of patients with asthma have BEC ≥ 0.3 x109 cells/l.7 Patients with allergic asthma may also have a raised BEC and patients with eosinophilic asthma may also have allergic sensitisations.

THE IMPORTANCE OF IDENTIFYING POTENTIAL SEVERE ASTHMA

The main reason to identify patients with potentially severe asthma is to reduce the morbidity associated with uncontrolled asthma and treatment (oral steroid)-related side effects, hospital admissions and deaths.

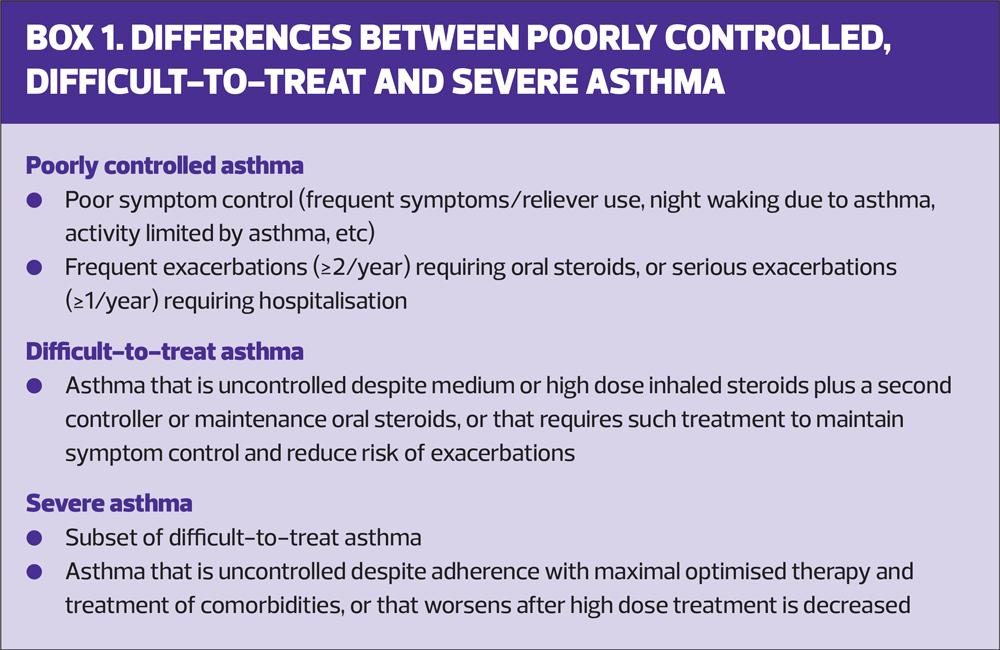

Frequent or regular use of OCS is associated with a number of side effects including:

- Osteoporosis

- Dyspeptic disorders

- Sleep disturbance

- Hypertension

- Diabetes

- Bone fractures, and

- Cataract.8

Importantly, each prescribed course of OCS results in a cumulative burden on current health and future risk of steroid-related complications, and the incidence of adverse events increases with each year of exposure.9 Figure 1 illustrates the most important types of OCS-related morbidity and their risk.

IDENTIFYING PATIENTS WITH POTENTIAL SEVERE ASTHMA

A key step is identifying patients with poorly controlled asthma. These include patients who have:

- Had ≥2 exacerbations (requiring treatment with oral steroids) in the past year OR

- Had ≥1 hospital admission due to asthma in the past year OR

- Requested ≥6 SABA (short-acting β-agonist) inhalers in the past year.11

While the annual asthma review will support the identification of these patients, patients may also be identified during an exacerbation review and, proactively, using integrated IT search tools. The Accelerated Access Collaborative, a unique collaboration hosted by NHS England and NHS Improvement, has worked with key stakeholders to create an electronic tool to help identify patients with poorly controlled asthma in primary care. The SPECTRA (Identification of SusPECted seveRe Asthma) tool (Table 1) identifies patients based on the above criteria, but many other search tools are available and it is recommended that they are implemented and reviewed on a 6-monthly basis.

MANAGEMENT IN PRIMARY CARE

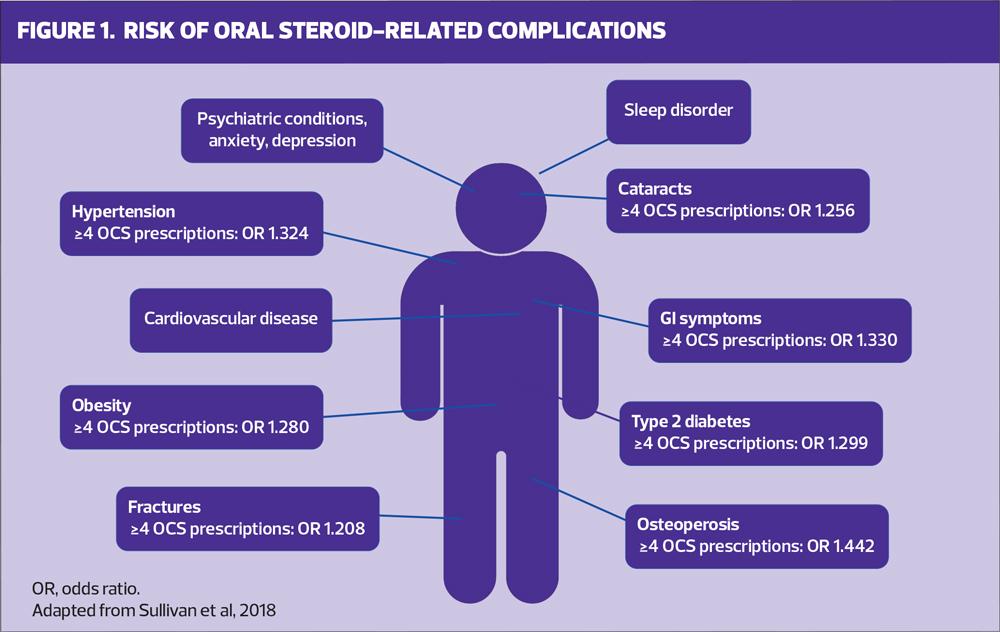

Once patients have been identified as having poorly controlled asthma, they should undergo a period of management, including assessment and treatment optimisation, in primary care. The management of all patients with asthma involves a similar, five step ‘asthma cycle’ (Figure 2).

Step 1. Diagnostic confirmation

Confirming that their symptoms are due to asthma may involve:

- Reviewing their medical history and any previous investigations (this may involve repeating previous tests such as spirometry, serial Peak Expiratory Flow Rate [PEFR])

- Considering additional investigations e.g. sputum culture, FeNO (if available)

- Considering other comorbidities that may be contributing to their symptoms e.g. allergic rhinitis and breathing pattern disorder.

Step 2. Optimising inhaler technique

Correct inhaler technique is the cornerstone to effective asthma control and errors range from insufficient inspiratory effort (made by 32-38% of dry-powder inhaler users), actuation before inhalation (made by 25% of metered-dose inhaler users), to failure to inhale a second dose.12

Unfortunately, it has been shown that health care professionals who care for patients with chronic respiratory diseases have insufficient knowledge about the correct use of inhaler devices. A systematic review found that inhaler technique was correct in only 16% of cases.13 Furthermore, patients’ technique has been shown to deteriorate over time and, even as early as 4 weeks after optimisation, a third of patients can have incorrect technique.14 Therefore:

- Provide inhaler technique advice and support at every interaction with the patient

- Make use of the many inhaler technique and education materials available to support patients and health care professionals (See Resources and Further Reading)

- Consider changing the device if the individual is unable to master the correct technique.

Step 3. Treatment adherence and escalation as per guidelines

Adherence to inhaler therapy is a particularly problematic area in asthma, and many studies have shown that adherence to inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) is less than 50%.15 Identifying and appropriately managing non-adherence can improve health care outcomes.16

Checking adherence to medication at every review and ensuring the medications are prescribed as part of a tailored personal asthma action plan (PAAP) will include:

- Asking about when and how often asthma medication is taken

- Counting how often patients pick up new or refill prescriptions and comparing it to how many inhalers they should be using. (Remember, however, that requests for a prescription may not always mean that the patient is collecting the medication from the pharmacy and they may still not use it as prescribed)

- Checking how much medication is left in the inhaler if it has a counter.

Once inhaler technique and adherence has been reviewed, treatment should be increased in a step-wise manner as per local and national guidance.

Step 4. Personalised asthma action plan, including advice on trigger avoidance

A co-written PAAP is key to supporting patients’ understanding and self-management of their asthma. It contains information on recommended steps should a patient experience a decline in symptoms and clear guidance on when to seek medical assistance. All patients with asthma should be provided with a PAAP that is updated regularly. Asthma triggers, how to avoid them and what to do if exposed to them should be included.

Allergy UK and the British Society for Allergy and Clinical Immunology have up to date trigger avoidance guidance and tools to support patients and clinicians. (See Resources and Further Reading).

Step 5. Lifestyle

It is widely recognised that lifestyle modification will improve lung health and any intervention should be actively encouraged. This will include:

- Encouraging a healthy balanced diet

- Promoting regular exercise and activity

- Avoiding unnecessary stress and anxiety

- Offering smoking cessation advice and support at every opportunity to improve symptoms, lung function and corticosteroid sensitivity.

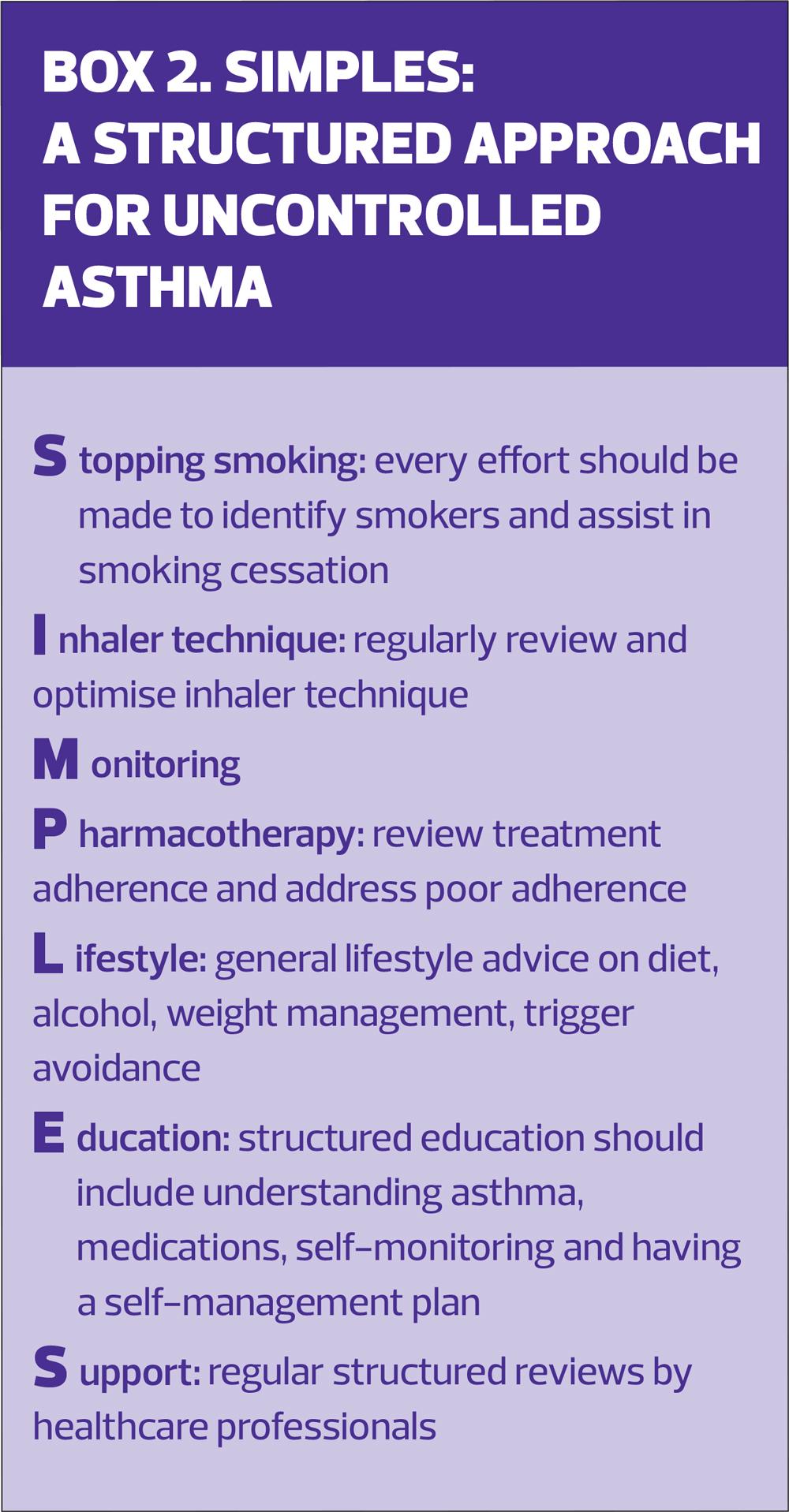

A structured approach (SIMPLES)

SIMPLES (Box 2) is a structured approach to the review of a person with poorly controlled asthma and provides a check-list that encompasses key components of an asthma review and interventions prior to considering referral to specialist care for further evaluation.17

WHEN TO REFER

If a patient remains uncontrolled, with ongoing exacerbations, high SABA use and ongoing symptoms, despite the SIMPLES steps, then referral to secondary or specialist care should be considered.

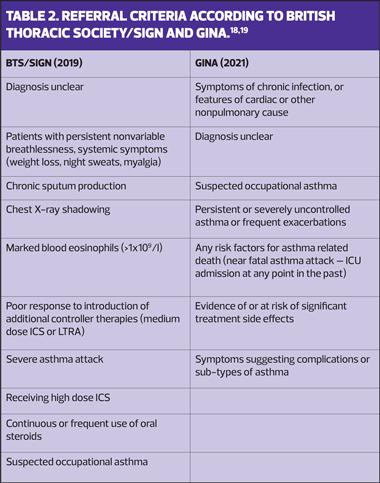

The Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA) guidelines and the British Thoracic Society/SIGN guidelines set out clear indications for referral to secondary and specialist care for asthma patients (Table 2).18,19

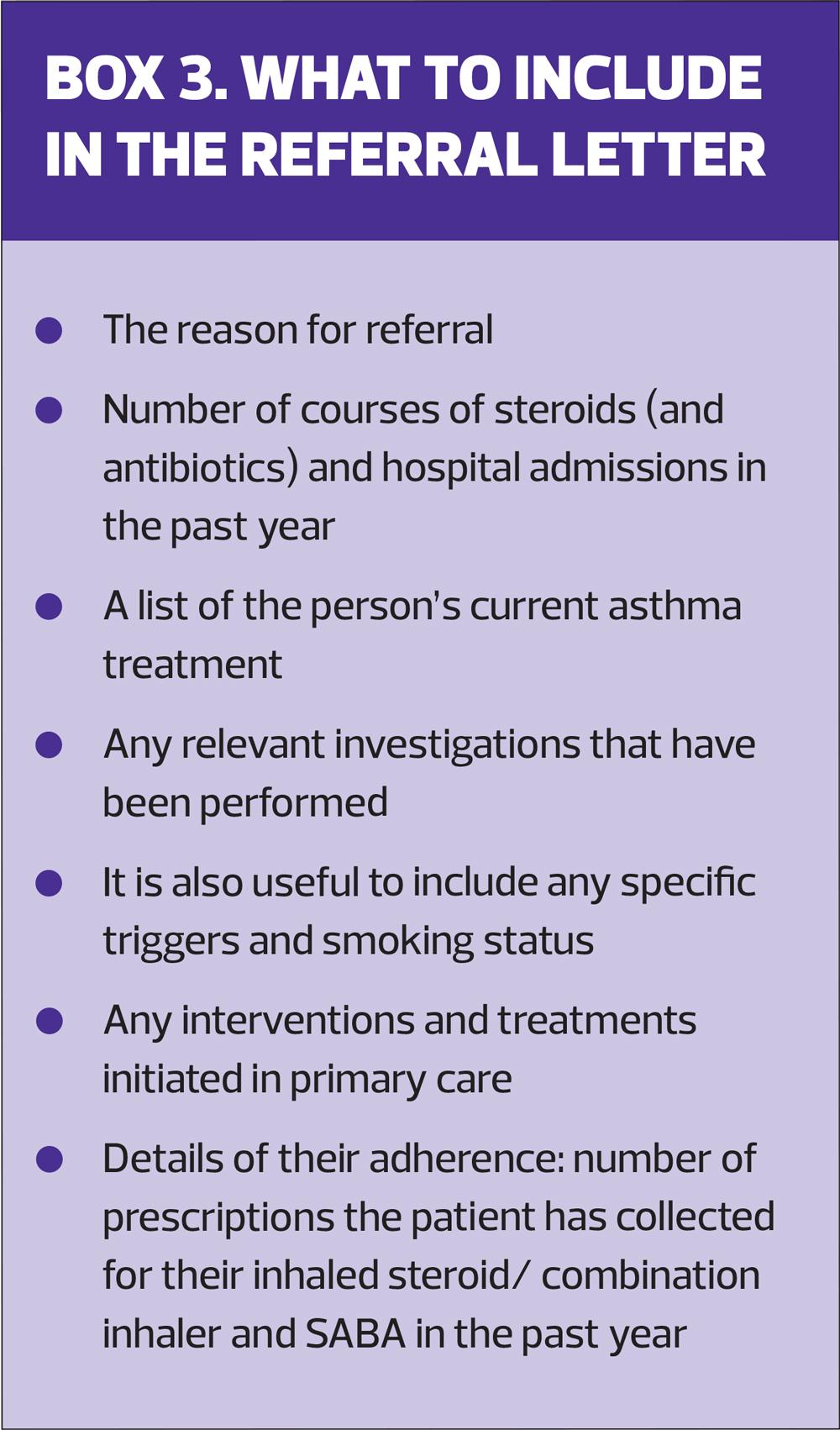

What to include in the referral letter

Box 3 outlines the important points to include. The SPECTRA tool, referred to earlier, also contains an asthma referral template that auto-populates relevant fields and can be used to facilitate the referral process.

WHAT HAPPENS IN SPECIALIST CENTRES

In most cases, the steps detailed in the ‘Asthma Cycle’ are repeated in specialist care with the support of a MDT, which may include specialist physiotherapists, speech and language therapists, dietitians, psychologists and pharmacists as well as specialist nurses.

A systematic MDT approach has been shown to improve asthma control, reduce OCS use and hospital admissions. Patients will require different levels of input from various members of the MDT and teams meet regularly to discuss patients and their progress. The case study opposite highlights the input from various members of the MDT.

ASTHMA BIOLOGICS

Biologic therapies are a relatively new class of medication. They work in a different way to traditional asthma treatments, targeting specific pathways that lead to inflammation in the airways. In the UK they are licenced for use in people who have severe allergic asthma or severe eosinophilic asthma, i.e. patients who remain uncontrolled despite treatment and adherence optimisation and comorbidity management,20 and their initiation requires approval from the severe asthma MDT. Currently, biologics are only initiated in severe asthma centres and select secondary care sites.

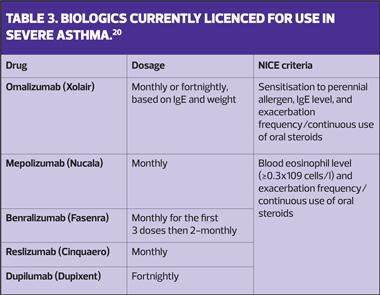

Omalizumab is licenced for use in patients with severe allergic asthma while mepolizumab, reslizumab and benralizuamb are licenced for use in patients with severe eosinophilic asthma. Table 3 lists the biologics that are currently licenced and the indications for their use. Additional biologics are currently in clinical trial stages and will be added to treatment algorithms in the future.

Asthma biologics have transformed the treatment of patients with severe allergic and severe eosinophilic asthma. In appropriately selected patients their use:

- Reduces asthma exacerbations

- Reduces dependence on daily steroids

- Improves lung function and quality of life.

In general, asthma exacerbations are reduced by at least 50% with 70% of patients receiving mepolizumab being able to reduce their daily OCS dependence by at least 50%,21 and one, single centre study of UK patients treated with benralizumab showed median reduction in maintenance OCS dose of 100% by 1 year.22

Response to the biologic is reviewed 16-24 weeks after initiation and then more formally by the MDT at 52 weeks. Biologic treatment is continued if there has been a clinically meaningful reduction in exacerbations and OCS dose (if patients are on daily steroids). Following this, their ongoing use is reviewed at least annually and continued use requires that:

- Reduction in exacerbations is maintained

- OCS dose is maintained or lower than at previous annual review

- Improvement in asthma control is maintained

- The patient has remained adherent to all their other prescribed asthma treatments.20

Patients who respond to biologics are likely to continue them long term unless they stop responding, develop side effect or contra-indications to asthma biologics. Considering this, most patients are taught to self-inject their biologic treatment at home (except patients on reslizumab as this is given intravenously). The time point that patients transfer to home self-administration varies between centres and is also dependent on clinical factors and patient related factors such as dexterity issues and availability of cold storage.

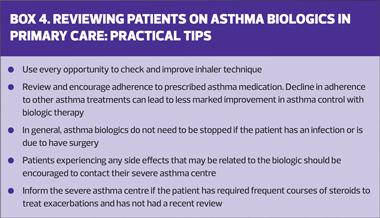

Practical tips for when patients on asthma biologics are reviewed in primary care are given in Box 4.

CASE STUDY

The referral letter

Please can you review this 46-year-old lady who has asthma. She is on Fostair 100/6 and montelukast. I am concerned because she has had 12 salbutamol inhalers in the last year, and 4 courses of oral steroids. Her inhaler technique has been checked and she was given a spacer last month. I also think she has a breathing pattern disorder, and I have directed her to some online resources. Her other medications include fluticasone nasal spray and an SSRI.

I am grateful for your review. Her most recent spirometry results are attached.

Treatment optimisation and additional investigations

Asthma nurse specialist review

- Inhaler technique

- Adherence management

Breathing pattern disorder

- Review by specialist respiratory physiotherapist

- 3 sessions

Psychologist review

- Acknowledged high levels of personal stress

- HADS: Anxiety = 11; depression = 12

- Did not believe that asthma was a serious condition

- 4 sessions

Chronic rhino-sinusitis

- Reviewed by ENT and treatment adjusted

- Did not need surgery

Dietitian review

- Salicylate sensitivity

- Dietary changes

Outcomes

- Remained uncontrolled

- Started on a biologic

CONCLUSION

Identifying patients with poorly controlled, difficult-to-treat and potential severe asthma is important as ‘SIMPLES’ treatment interventions can help improve their asthma control and reduce exacerbations. Patients who remain uncontrolled despite a period of assessment and management in primary care should be referred to secondary or specialist asthma centres for a systematic assessment using MDT support. Patients who remain symptomatic despite treatment and adherence optimisation and comorbidity management should be considered for advanced therapies such as asthma biologics to help reduce exacerbations, oral steroid use and related side effects.

REFERENCES

1. Asthma UK. Asthma facts and statistics. 2021 https://www.asthma.org.uk/about/media/facts-and-statistics/

2. Royal College of Physicians. Why asthma still kills: National Review of Asthma deaths;2015 https://www.rcplondon.ac.uk/projects/outputs/why-asthma-still-kills.

3. Denton E, Lee J, Tay T, et al. Systematic assessment for difficult and severe asthma improves outcomes and halves oral corticosteroid burden independent of monoclonal biologic use. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract 2020;8(5):1616-1624.

4. Ryan D, Heatley H, Heaney LG, et al. Potential severe asthma hidden in UK primary care. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract 2020;9(4):1613-23.

5. Price D, Fletcher M, van der Molen T. Asthma control and management in 8,000 European patients: the REcognise Asthma and LInk to Symptoms and Experience (REALISE) survey. NPJ Prim Care Respir Med. 2014;24:14009.

6. Hekking P-PW, Wener RR, Amelink M, et al. The prevalence of severe refractory asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2015;135(4):896-902.

7. Kerkhof M, Tran TN, Allehebi R, et al. Asthma phenotyping in primary care: applying the international severe asthma registry eosinophil phenotype algorithm across all asthma severities. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract 2021 https://www.jaci-inpractice.org/article/S2213-2198(21)00897-7/fulltext

8. Price D, Castro M, Bourdin A, et al. Short-course systemic corticosteroids in asthma: striking the balance between efficacy and safety. Eur Respir Rev 2020;29(155):190151.

9. Sullivan PW, Ghushchyan VH, Globe G, Schatz M. Oral corticosteroid exposure and adverse effects in asthmatic patients. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2018;141(1):110-116.e117.

10. Cataldo D, Louis R, Michils A, et al. Severe asthma: oral corticosteroid alternatives and the need for optimal referral pathways. J Asthma 2021;58(4):448-458.

11. Holmes S, Kane B, Pugh A, et al. Poorly controlled and severe asthma: triggers for referral for adult and paediatric specialist care – A PCRS pragmatic guide. Primary Care Respiratory Update 2019. Issue 8, 22-27 https://www.pcrs-uk.org/sites/pcrs-uk.org/files/_SevereAsthmaReferral.pdf

12. Price DB, Román-Rodríguez M, McQueen RB, et al. Inhaler errors in the CRITIKAL study: type, frequency, and association with asthma outcomes. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract 2017;5(4):1071-1081.e1079.

13. Plaza V, Giner J, Rodrigo GJ, et al. Errors in the use of inhalers by health care professionals: a systematic review. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract 2018;6(3):987-995.

14. Ovchinikova L, Smith L, Bosnic-Anticevich S. Inhaler technique maintenance: gaining an understanding from the patient's perspective. J Asthma 2011;48(6):616-624.

15. Dima AL, Hernandez G, Cunillera O, et al. Asthma inhaler adherence determinants in adults: systematic review of observational data. Eur Respir J 2015;45(4):994.

16. Gamble J, Stevenson M, Heaney LG. A study of a multi-level intervention to improve non-adherence in difficult to control asthma. Respir Med 2011;105(9):1308-1315.

17. Ryan D, Murphy A, Stallberg B, et al. ‘SIMPLES’: a structured primary care approach to adults with difficult asthma. Prim Care Respir J 2013;22(3):365-373.

18. Global Initiative for Asthma. Global Strategy for Asthma Managment and Prevention. https://ginasthma.org/gina-reports/

19. BTS/SIGN Guideline for the management of asthma. 2019; https://www.brit-thoracic.org.uk/quality-improvement/guidelines/asthma/.

20. Rupani H, Murphy A, Bluer K, et al. Biologics in severe asthma: which one, when and where? Clin Exper Allergy 2021;51(9):1225-1228.

21. Kavanagh JE, d' Ancona G, Elstad M, et al. Real-world effectiveness and the characteristics of a “Super-Responder” to mepolizumab in severe eosinophilic asthma. Chest 2020;158(2):491-500.

22. Kavanagh JE, Hearn AP, Dhariwal J, et al. Real-world effectiveness of benralizumab in severe eosinophilic asthma. Chest 2021;159(2):496-506.

Related articles

View all Articles