Getting patients to stop smoking: do the drugs work?

DR ED WARREN

DR ED WARREN

FRCGP, FAcadMEd

Next month sees national No Smoking Day, when there is usually a spike in the numbers of quit attempts. But how can you support patients to stop smoking, and what are the most effective pharmacological aids?

Smokers are, by definition, more likely to have smoking-related disease, and will often be seen in general practice nurse (GPN)-run chronic disease management clinics. For others, smoking will be exacerbating another problem, such as the catarrh associated with the common cold, so that smokers are more likely to present on triage. Smoking is also associated with other factors that lead to increased consultation – in particular social deprivation and mental illness. Some GPNs may run their own smoking-cessation clinics. One way or another, you are likely to encounter significant numbers of smokers.

AUSTERITY

The Government is sending out mixed messages. On the one hand it has announced that prevention is to be at the centre of development plans for the NHS.1

It will be spending £157m on a scheme that targets smokers who are admitted to hospital.2 There is apparently no UK evidence that the scheme will work – it is being trialled in Manchester but the results are as yet unpublished. The only evidence comes from Canada where the ‘Ottawa Model’ of counselling and medication increased the number of non-smokers at 6 months from about 20% to about 30%,3 and decreased the rate of hospital re-admission by around a third on 2-year follow-up.4

On the other hand, since the Health and Social Care Act (2012) local councils have been responsible for public health, including smoking cessation programmes. The government grant to councils has been seriously reduced, and since statutory services (including child safeguarding) have to be maintained, the amount spent by councils on smoking cessation has of necessity been hit disproportionately, decreasing by 14% from 2016 to 2019. Indeed some councils, to balance their books, have stopped all of their smoking cessation services.5

This is regrettable as the number of smokers in the UK has recently been falling and it would be good to sustain this progress. The UK prevalence of smoking in the over-18s is now around 15%, with slight variation within the four countries. At its peak in 1948, 82% of the male population and 41% of women smoked. This stayed about the same until the 1970s, and then fell – quickly at first, but more slowly later – to present figures (from 2017).6 However, smoking still caused 78,000 deaths in England in 2015.6 Smoking prevalence is higher among the socially deprived and those with mental health problems. At over 25%, the smoking rate among manual workers is two and a half times higher than for those in professional jobs.6

SMOKING IS BAD FOR YOU

The earliest reference to tobacco smoking comes from two Spaniards writing in 1492 who saw American natives ‘drinking smoke’.7 Tobacco was allegedly introduced into Britain by Sir Walter Raleigh, who was subsequently executed (for treason and not for his role in tobacco use). During both World Wars, cigarette smoking was positively encouraged among servicemen as a comfort and as an aid to enduring life in the trenches.8

Even in the early days there were concerns about the safety of tobacco. King James I famously described smoking as ‘Hateful to the nose, harmful to the brain and dangerous to the lungs.’9

In 1642 the Pope threatened snuff users with excommunication. In Turkey smoking was a capital offence while the Emperor of Russia ordered that ‘tobacco drinkers’ should have their noses slit.7

The first incontrovertible evidence of the harms of smoking came in 1954 with the publication by Doll and Bradford-Hill of their study looking at the smoking habits and mortality rates of British doctors.10 In more than 60 years since then, nobody has had a good word to say in favour of tobacco smoking, except that it might just possibly protect against Parkinson’s disease.11

There are about 7,000 different chemicals in tobacco smoke.12 Around 250 are known to be harmful, including hydrogen cyanide, carbon monoxide and ammonia (added by manufacturers to increase the addictive effects of smoking).13 At least 69 of these are carcinogenic, including arsenic, benzene and cadmium.12 It is the nicotine that causes the addiction, and the other chemicals that kill and maim you.

THE GUIDELINES

So, how do you get people to stop smoking? NICE/CKS issued updated guidance in March 2018.14

Hunt the smoker

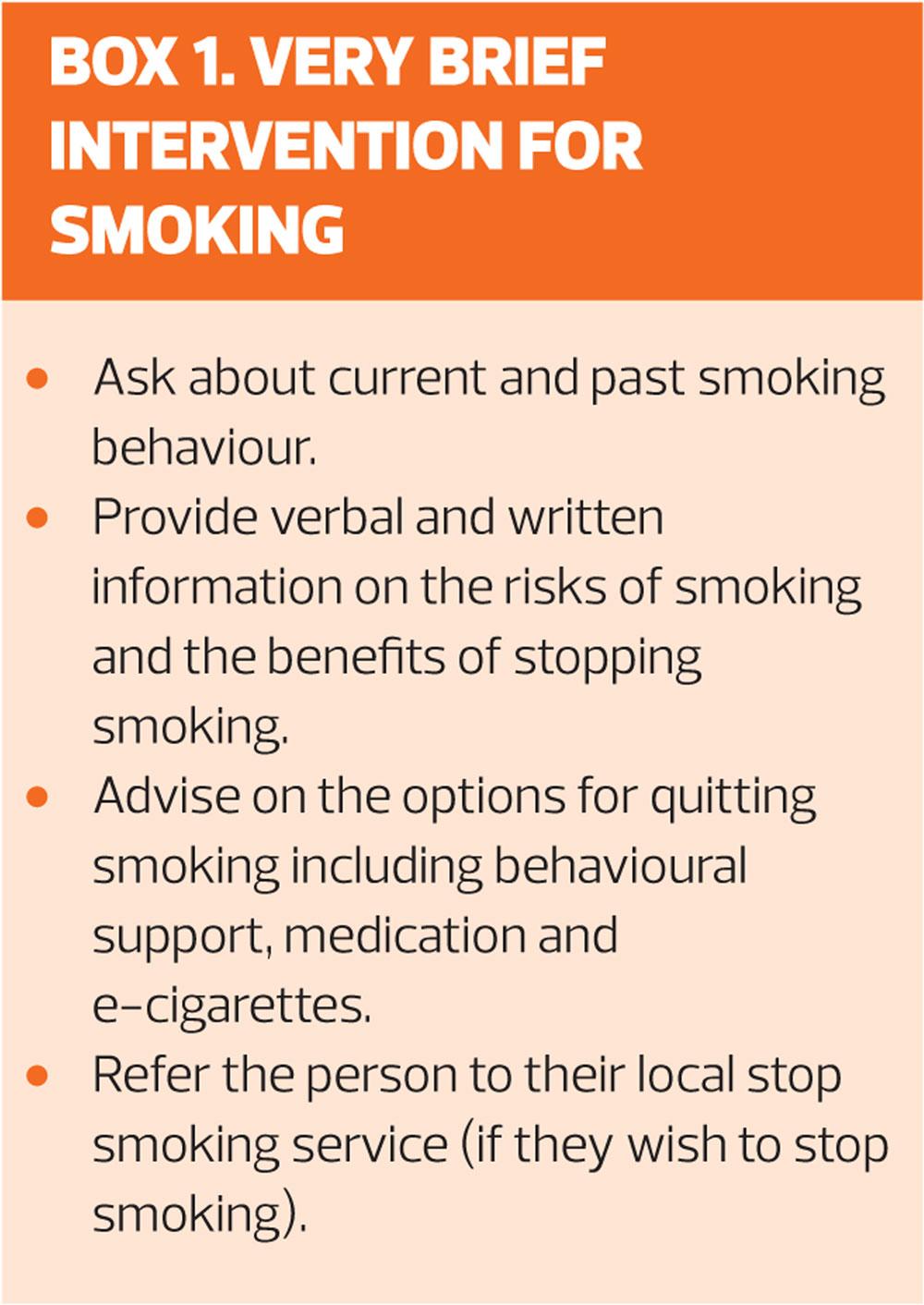

Ask patients at every opportunity whether they smoke. If they do, try Very Brief Intervention (VBI). This should take no more than 30 seconds – see Box 1. Over 60% of current smokers say that they want to stop, and under 20% say they have no intention of ever stopping.6 About 40% of smokers try and stop at least once each year, but only about 5% are successful.15 For those who do not wish to stop smoking, give advice about harm reduction. NICE guidance on smoking harm reduction is available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ph45.16

Assess the smoker

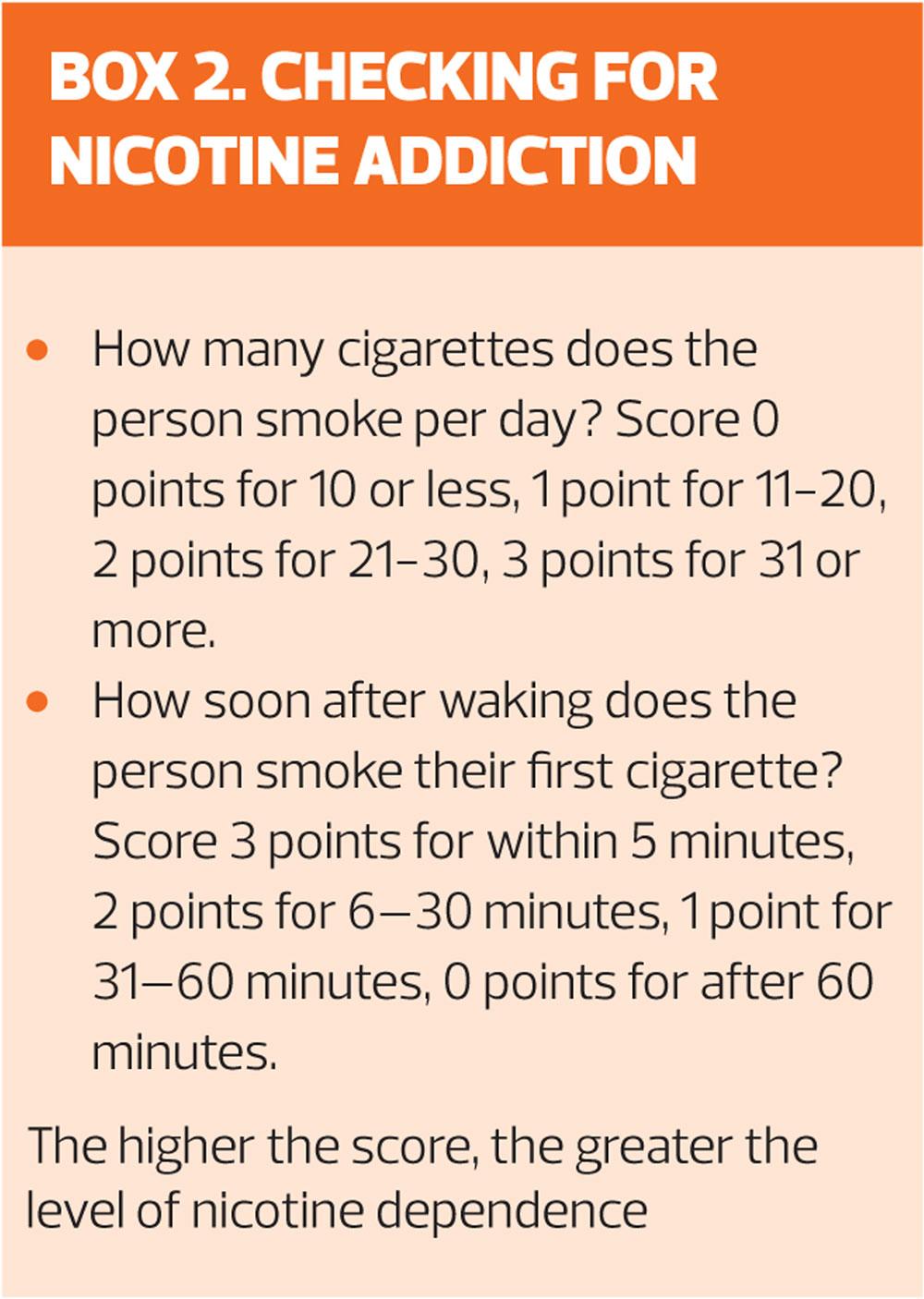

Is there evidence of nicotine addiction? About 43% of smokers are physically addicted to nicotine,6 and rather more smokers fear to stop because they think they are addicted. A brief guide to assessing if a smoker is addicted is given in Box 2. It is plausible that the addicts will respond better to medications, and the non-addicts will respond better to behavioural support.

What have you tried so far?

Most smokers try to stop more than once before success: depending on how you do the research it takes between 6 and 142 attempts before success.17 There is no cause for despondency at this poor success rate. Multiple quit attempts will usually result in a reduction in the lifetime consumption of tobacco – even a failed attempt is better than nothing.

Ask about previous attempts to quit

- How successful were you?

- Did you try any drug treatment?

- Did you use any support, for example through a smoking cessation service?

- What were your experiences of withdrawal symptoms and cravings?

Any complicating factors?

Some smokers may also be (other) drug users, have mental health issues, or may already have a smoking-related disease (e.g. lung cancer). Others may have ongoing illness that is exacerbated by smoking (e.g. COPD, diabetes). Smoking alters the bioavailability of some drugs, so that the dosages may need adjusting when smoking has ceased (e.g. olanzapine, warfarin, metformin).

MEDICATION FOR SMOKING CESSATION

There are three medications licensed in the UK which have proven efficacy in smoking cessation:

- Nicotine Replacement Therapy – NRT (patches, oral preparations such as gum or lozenges, nasal sprays, inhalators)

- Oral varenicline

- Oral bupropion

Some people want to try to stop smoking using e-cigarettes, but these cannot currently be prescribed (or supplied by smoking cessation services), so it recommended that they use one of the above licensed medications instead.14 Though e-cigarettes almost certainly carry fewer dangers than smoking real cigarettes, nevertheless it is not yet clear if they are safe long-term. E-cigarette use alone or in combination with licensed medication and behavioural support appears to be helpful in the short term but further research is needed to establish the role of e-cigarettes in smoking cessation.14

For smokers who do not want to stop, then further intervention at this point is inappropriate. However, you might warn them that their records have been flagged, and that their GP and GPN will be obliged to ask them about their smoking every time they seek healthcare. The danger is that the smoker then avoids seeing a healthcare professional because they fear either being browbeaten, or because they fear that every ailment will be attributed to the smoking. It is not clear from the literature how damaging this healthcare avoidance might be.

For smokers who do want to stop, then referral to a specialised NHS Stop Smoking service is advised.14 Psychosocial support is available, and there will also be a mechanism for issuing smoking cessation medication. For smokers who cannot or will not go to the Stop Smoking service, but who still want to stop smoking, then the responsibility rests with primary care.

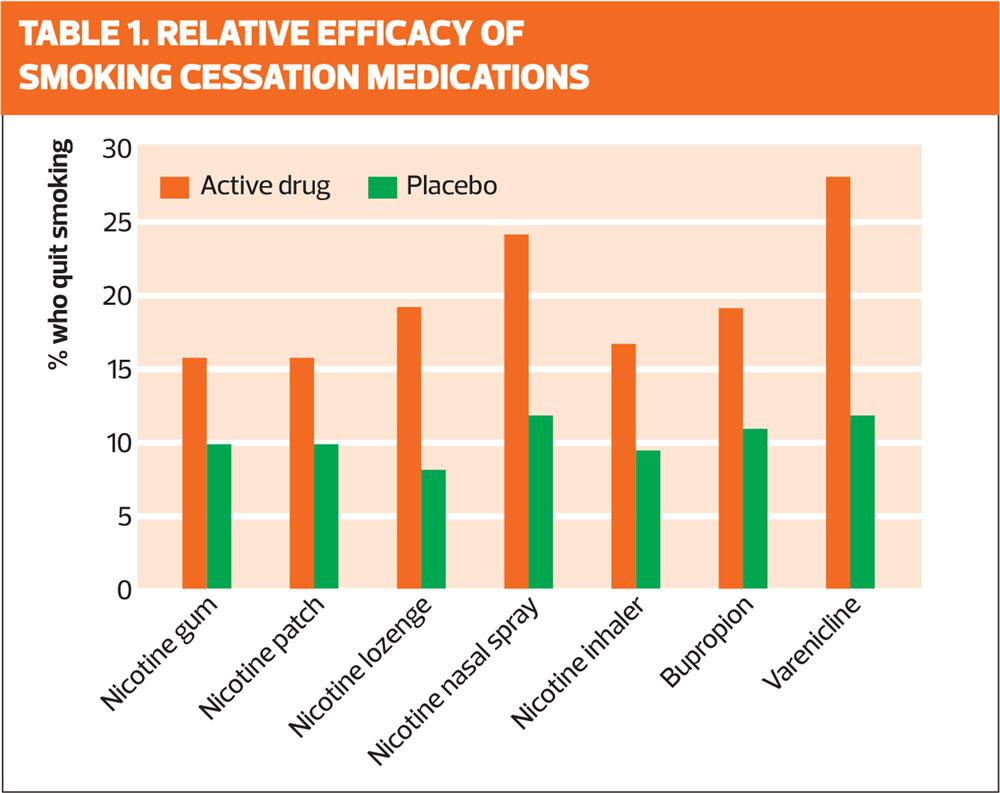

The relative efficacy of the available smoking-cessation medications, based on data from the Cochrane Collaborative,15 is shown in Table 1. From this it would look as though varenicline and nicotine nasal spray have the best chance of success. However, choice of medication should be guided by patient preference and also by any pre-existing illness or ongoing medication. If something has worked before, it might be worth trying it again, or else (as there has been a relapse) trying something else. All medications work best when used in conjunction with behavioural support.14

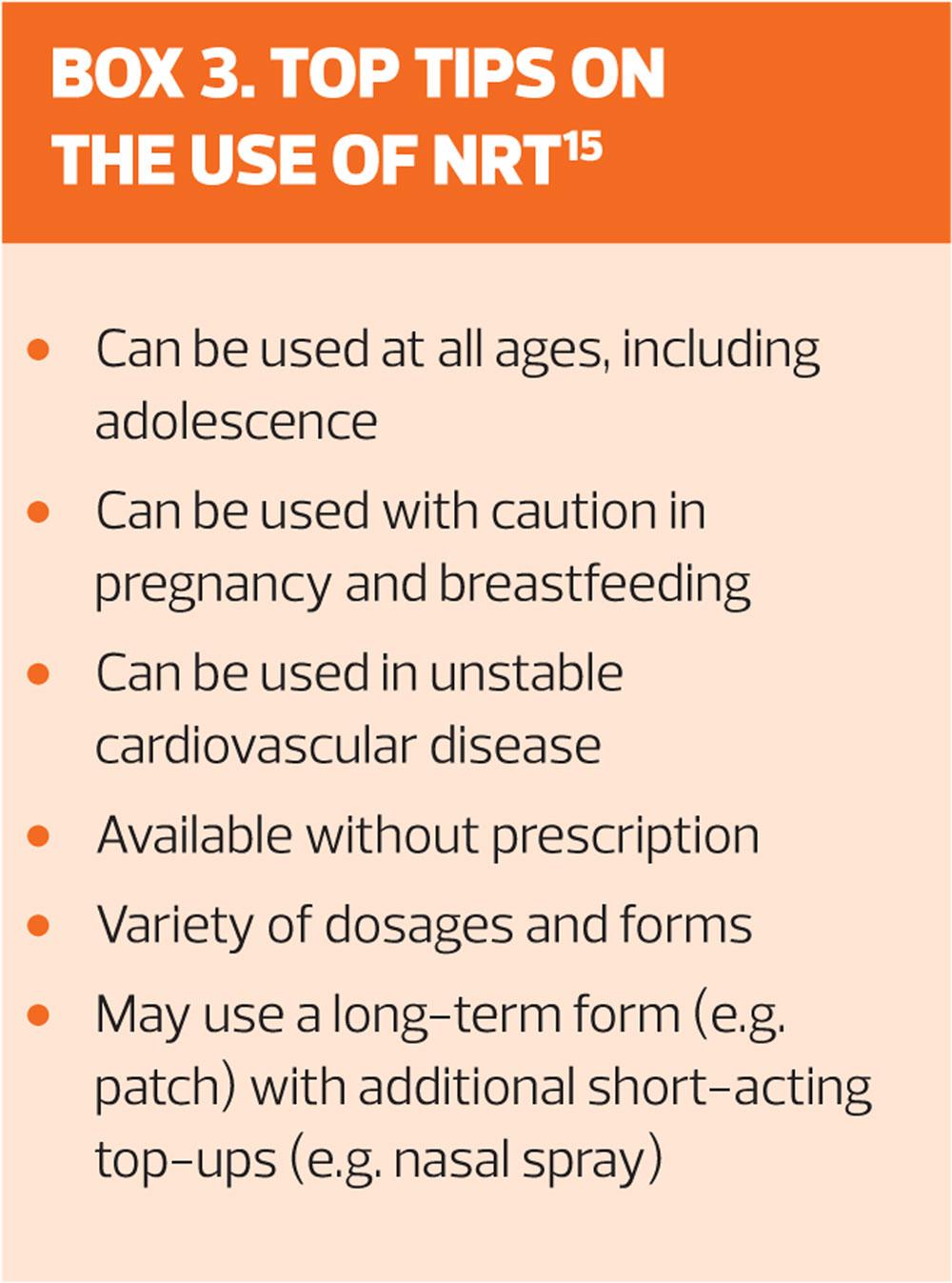

NICOTINE REPLACEMENT THERAPY (NRT)

NRT (Box 3) delivers nicotine at a lower concentration and more slowly than cigarettes, so it is plausible that the risks are lower. NRT may cause chest pain and palpitations, but it does not cause cardiac ischaemia.18

The patches are used for 16 hours and then taken off at night. If there is evidence of nicotine addiction (see earlier) then leave the patch on for 24 hours (16 hour and 24 hour patches are available). Branded products are recommended as the doses are different and bioavailability may vary.14 Each brand of patch is made in a number of doses, and it is usual to start on the highest dose.

Start use on the ‘quit day’ with a higher dose patch. This may be topped-up as needed with an oral preparation or a spray. There is good evidence to show that combination NRT is more effective than single product use,19 and this approach is recommended by NICE. Avoid fruit juice or coffee in the 15 minutes before using oral NRT – a tricky restriction as oral NRT tends to be used to overcome cravings, and you may not get much warning of these.

Treatment usually persists for 8 to 12 weeks, but longer durations and higher doses may be needed in the more dependent smokers. Since NRT is available without prescription, it is not unknown for patients to use patches and also smoke cigarettes – not an ideal situation, but it is to be hoped that at least the number of cigarettes used is reduced.

Usually the dose of NRT is tapered down to nothing, and the individual product instructions give advice on this. Apparently whether you stop suddenly or gradually has little effect on the long-term outcome of the treatment.14

About 20% of patch users get irritation where the patch is applied, but rarely is this so bad that treatment has to be stopped.20 Other side effects include dizziness, headache, sleep disturbance, agitation, irritability, fatigue, gastro-intestinal upset, dry mouth, cough, muscle pain, joint pain, palpitations, tingling, tremor, anxiety, dyspnoea. The nasal spray can cause nosebleeds and runny eyes. Oral preparations can cause sore mouth and tongue, or hiccoughs.20

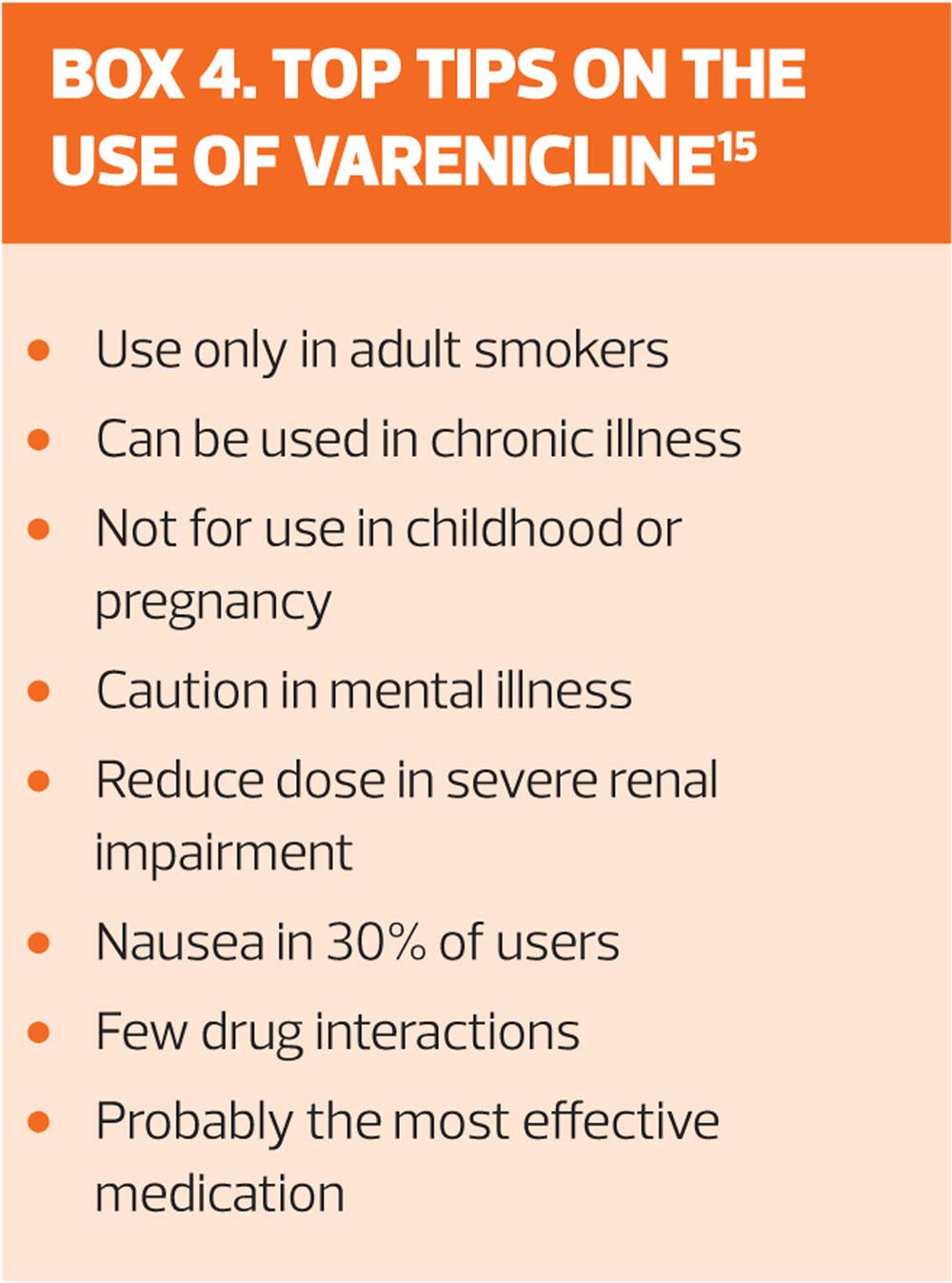

Varenicline

Oral varenicline (Box 4) is a partial nicotine receptor agonist that binds less effectively than nicotine.18

The tablet should be started 7 to 14 days before ‘quit day’, meaning that the tablets are started while the smoker is still smoking. The ‘quit day’ is the day when smoking stops – the ‘not a puff rule’ is advised, i.e. the ex-smoker should not have any tobacco, not even a single puff. The tablet regime is:

Day 1 to 3 – 500mcg once daily

Day 4 to 7 – 500mcg twice daily

Day 8 onwards – 1mg twice daily

(If the full dose can’t be tolerated, revert to 500mcg twice daily)

Varenicline is available in a ‘starter pack’ with the right doses to achieve this build-up of treatment.

The maximum tolerated dose is taken for 12 weeks, with an option to continue for another 12 weeks if required. The medication is then stopped, without tapering the dose. In 3% of cases there is a reaction to stopping – irritability, depression, insomnia, urge to smoke: if this happens then tapering the dose down is a better idea.14

Concerns about varenicline causing neuropsychiatric or cardiac events have not been confirmed by placebo-controlled trials.18 MIMS gives details of a range of other adverse effects, including: headache; abnormal dreams; insomnia; appetite change; weight gain (never popular); fatigue; toothache; dry mouth; cough.20 Nearly 10% of people stop varenicline because of side effects, but in the same study 8% of the placebo group also stopped their tablets.21

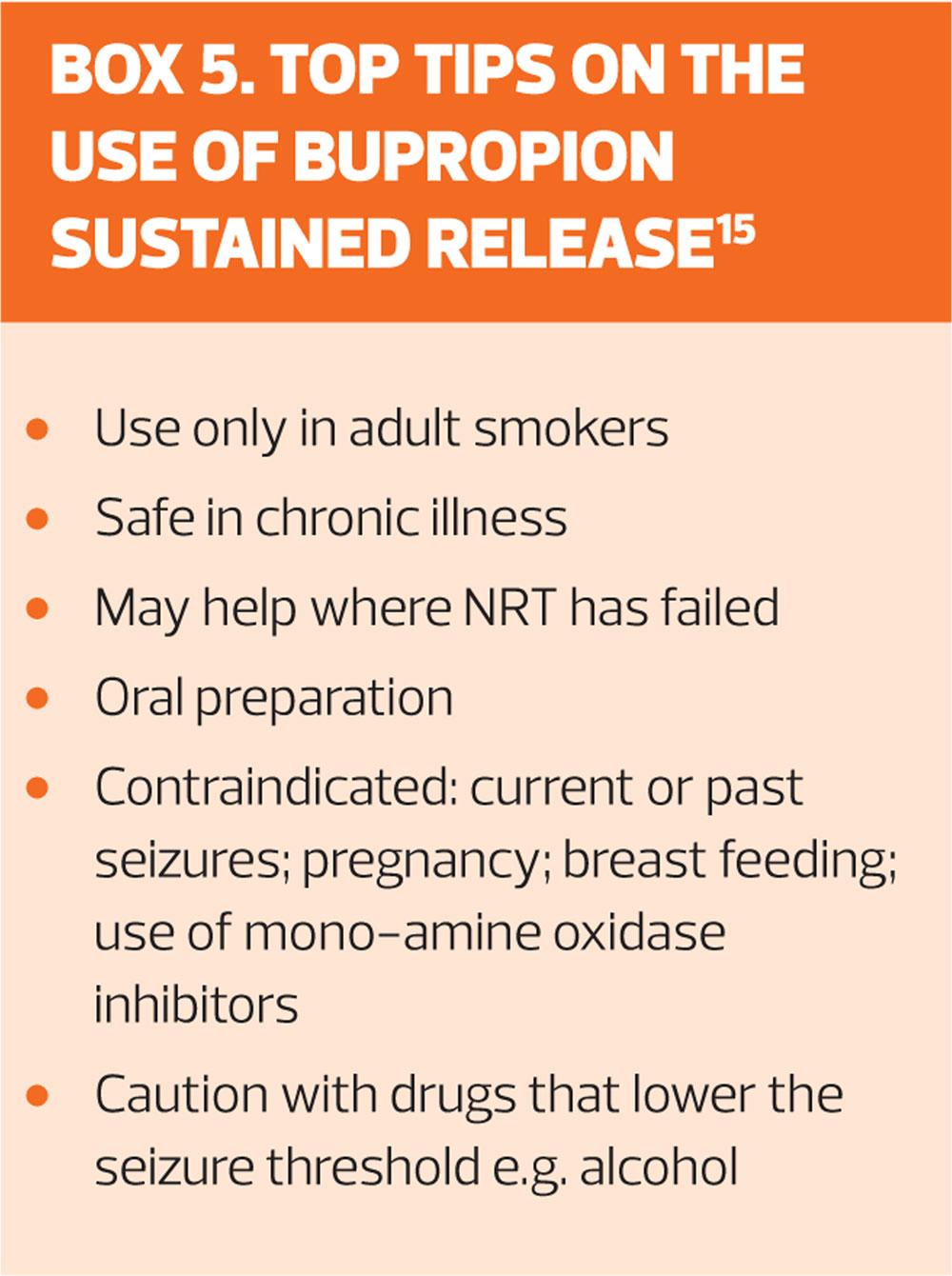

Bupropion

Bupropion (Box 5) was developed as a possible treatment for depression: it is used for depression in some countries, but does not have a UK licence for this use. In smoking cessation it appears to work by blocking nicotine receptors – it is a nicotine receptor antagonist. In addition it mimics the actions of dopamine and noradrenaline, two mood chemicals. So as well as blocking the effects of nicotine withdrawal, it reduces any resulting mood depression.18

The tablets are to be started between 7 and 14 days before the ‘quit day’. The doses are 150mg once daily for six days, and then 150mg twice daily for 7 to 9 weeks. If it has not worked after 7 weeks, then stop the drug.14 In the elderly, and those with hepatic or renal impairment (eGFR of less than 50 ml/min), then keep the dose at 150mg once daily. Treatment can be stopped suddenly or tapered down – it does not appear to matter.

A concern about bupropion is that it causes fits: it does, but in only around 0.1% of users.20 Another concern raised in post-marketing surveillance was that it causes possible psychiatric side effects, including behaviour changes, depression, hostility and attempted suicide. Formal trials have failed to confirm this fear.20 Nevertheless, bupropion is contraindicated in smokers under 18 years old; past or present seizures; brain tumour; current or previous eating disorder; bipolar disorder or severe liver cirrhosis.14

Caution should be exercised when using bupropion in smokers who have conditions that may reduce the epileptic threshold (alcohol abuse; past brain injury; diabetes; taking drugs, such as antipsychotics, that make seizures more likely; taking stimulants or slimming pills) or who have severe hepatic or renal impairment.

Patients taking bupropion should nevertheless be monitored for psychiatric side effects – overall the evidence suggests that there is not a problem, but this encompasses trials that do show a risk and trials that don’t so that evidence is conflicting. Between 30% and 40% of takers get insomnia, and 10% get a dry mouth. Between 7% and 12% of patients stop bupropion because of side effects.20

CONCLUSION

Far fewer people smoke in the UK now than used to be the case, largely because of several measures outside of the normal remit of healthcare workers – price increases, bans on advertising, bans on public smoking. Nevertheless 15% of adults continue to smoke, and there is a steep social-class gradient so that smoking is yet another factor that disproportionately disadvantages the poor. Nearly 80,000 deaths a year is still a very significant figure.

As with all behavioural changes, there is a strong psychological component to smoking cessation, and whatever else is done smokers trying to stop benefit from support. Although a patient who shifts from real cigarettes to e-cigarettes is almost certainly at less peril from their habit, the role of e-cigarettes has yet to be established. There are other fringe treatments around, but none yet merits serious consideration. The three main drug treatments all have a good track record, and which to use depends on patient preference.

REFERENCES

1. The NHS long term plan, 2019. https://www.longtermplan.nhs.uk/online-version/

2. Dalton D. All smokers admitted to hospital will be offered help to quit in new NHS drive to highlight personal responsibility for health. Independent 5 January 2019

3. Reid RD, Mullen K-A, Slovinec D’Angelo, et al. Smoking cessation for hospitalized smokers: An evaluation of the “Ottawa Model”. Nicotine & Tobacco Research 2010;12(1):11–18,

4. Mullen K-A, Manuel DG, Hawken SJ. Effectiveness of a hospital-initiated smoking cessation programme: 2-year health and healthcare outcomes. Tobacco Control 2017;26:293-299 https://tobaccocontrol.bmj.com/content/26/3/293

5. Iacobucci G. Stop smoking services: BMJ analysis shows how councils are stubbing them out. BMJ 2018;362:k3649

6. Action on Smoking and Health (ASH). Fact sheet no. 1: Smoking statistics. http://ash.org.uk/category/information-and-resources/fact-sheets/

7. Ainsworth S. Tobacco – from cure to curse. General Practitioner October 22 1999:100-1.

8. Wrigley C. Smoking for King and Country. History Today April 2014;24-30.

9. Fowler G. Anti-smoking advice in general practice. Respiratory Diseases in Practice August/September 1989:22-7.

10. Doll R, Bradford-Hill A. The mortality of doctors in relation to their smoking habits. Br Med J 1954 Jun 26;1(4877): 1451-55

11. Parkinson’s UK. People who smoke may be less likely to develop Parkinson’s, 2018. https://www.parkinsons.org.uk/news/people-who-smoke-may-be-less-likely-develop-parkinsons

12. ASH. Facts at a glance – key smoking statistics. http://ash.org.uk/category/information-and-resources/fact-sheets/

13. McKee M. The marketing push that surprised everyone. BMJ 2013;347:f5780.

14. NICE/CKS. Smoking cessation. https://cks.nice.org.uk/smoking-cessation

15. Zwar AN, Mendelsohn CP, Richmond RL. Supporting smoking cessation. BMJ 2014;348:f7535.

16. NICE PH45. Smoking: harm reduction, 2013. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ph45.

17. Chaiton M, Diemert L, Cohen JE et al. Estimating the number of quit attempts it takes to quit smoking successfully in a longitudinal cohort of smokers http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2016-011045

18. Hartmann-Boyce J and Aveyard P. Drugs for smoking cessation. BMJ 2016;352:i571.

19. Avery P. Combination nicotine replacement therapy (NRT), 2012. National Centre for Smoking Cessation and Training (NCSCT). http://www.ncsct.co.uk/usr/pub/Briefing%203.pdf

20. Monthly Index of Medical Specialities (MIMS). https://www.mims.co.uk/

21. Cahill K, Stevens S, Perera R, et al. Pharmacological interventions for smoking cessation: an overview and network meta-analysis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2013;5:CD009329.23728690.

Related articles

View all Articles