Interstitial Lung Disease

JANE SCULLION

JANE SCULLION

MSc, BA(Hons), RGN.

Nurse consultant, University Hospitals of Leicester. Trustee Education for Health

STEVE HOLMES

MMedSci, MBChB, FRCGP, DRCOG. General Practitioner, The Park Medical Practice, Shepton Mallet, Somerset. Trustee, Education for Health

The recent death of Keith Chegwin at a young age has turned the spotlight on a poorly understood, frequently missed or misdiagnosed group of conditions. Would you be able to recognise the red flags and be able to support patients with these disabling, potentially life-limiting illnesses?

LEARNING OUTCOMES

After working through this article you will be able to:

- Describe the effects of an ILD on lung tissue and list the potential causes of this group of conditions

- Discuss the prevalence of ILD and the factors that may be linked to the apparent increase of some forms of ILD

- List the drugs commonly associated with drug-induced ILD

- Identify the major ‘red flags’ that should prompt consideration of specialist referral

- Discuss the investigations that would be appropriate to undertake prior to specialist referral

- Discuss the general management principles of ILD applicable to primary care settings.

The group of lung diseases known as Interstitial Lung Diseases (ILDs) are varied, with around 300 recognised variations.1 These are, in essence, diseases affecting the interstitium (tissue) of the lung rather than the airways, as in asthma and COPD. The symptoms of ILDs and airway disease, however, are often very similar.

The ILDs can present acutely or chronically, and in a variety of ways. A major problem is that the diagnosis is often missed, in both primary and secondary care, for a considerable period of time.2,3 This results in late or confused diagnosis, and subsequent incorrect or delayed treatment.

A programme, based on a regional model, usually with a centre (hub), with expertise from other specialities, as well as respiratory, is being rolled out in England to ensure accurate, evidence based diagnosis.3,4 Already this is having positive effects, with patients having their cases discussed at regional, multidisciplinary team (MDT) meetings.

WHAT IS ILD?

ILD covers a range of distinct, potentially life-limiting conditions that affect the ability to absorb oxygen into the bloodstream. The effect of an ILD on the tissue of the lung varies and will include one or more of the following:

- Fibrosis

- Inflammation

- Granulation.

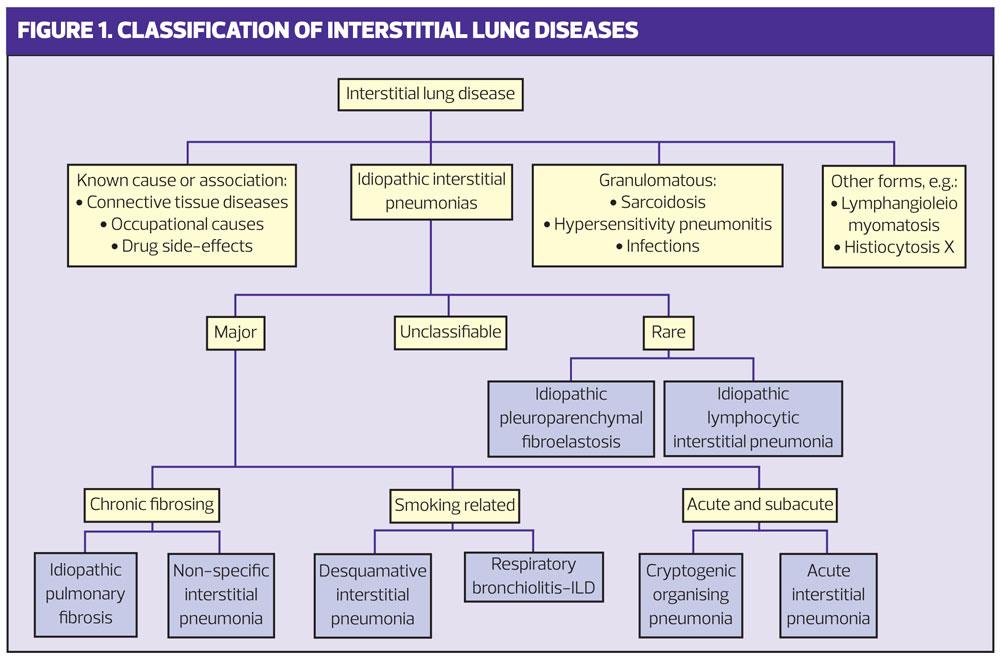

Classification of the various disease processes is based on these effects.5 (Figure 1)

ILDs make the lung volumes smaller, known as restriction, causing breathlessness and sometimes cough. However, not all restrictive problems are ILD, e.g. lung cancer and pleural effusions, and the disease often has to have progressed significantly for restriction to be evident on spirometry. Spirometry is therefore not a useful screening tool.

These conditions have different causes and different treatments. Indeed, treatments that can be effective in one ILD (such as immunomodulation in auto-immune ILD) are now known to cause increased mortality in another.6 The medical management of ILD has become progressively more reliant on specialist input as it becomes more complex and nuanced.

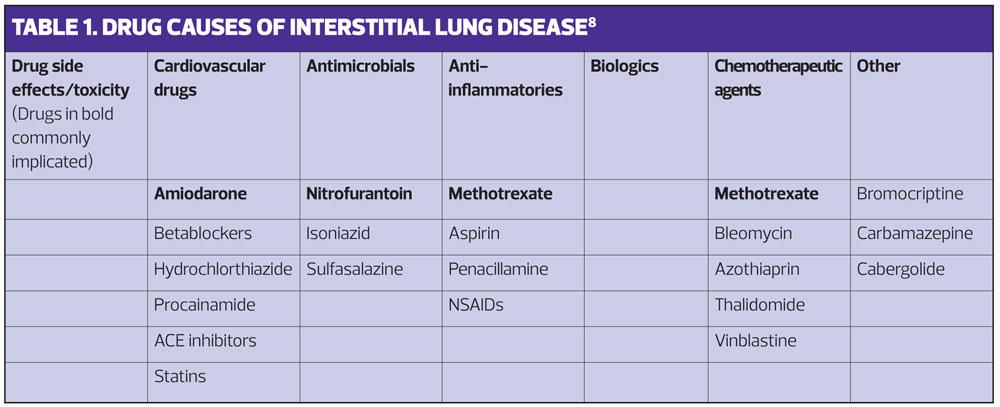

As well as varying in their causes and treatment, these disorders vary in both their impact and prognosis. Some, such as sarcoid, have a range of manifestations from causing minimal unnoticeable damage to progression and death.7 Because there are so many manifestations of ILD we need to think widely about possible causes and take a good history to look for possible associations.8 (Table 1).

ILD TYPES

Drug-induced ILD (DILD)

As well as other causes of ILD it is important to think about medication. It is all too easy to continue medication if an association with presenting symptoms is not considered. Some of the commoner drugs that have been associated with development of DILD include:

- Antimicrobials, e.g. isoniazid, nitrofurantoin, sulfasalazine

- Anti-inflammatory agents, e.g. aspirin, methotrexate, NSAIDs, penicillamine

- Biologic agents

- Cardiovascular agents, e.g. ACE inhibitors, amiodarone, beta blockers, hydrochlorothiazide, procainamide, statins

- Chemotherapeutic agents, e.g. azathioprine, methotrexate, thalidomide, vinblastine

- Other agents, e.g. bromocriptine, carbamazepine, cabergolide, methysergide, opiates, phenytoin, talc.

DILD secondary to long term nitrofurantoin (8-16 months) is common in the elderly and most cases have occurred in females. Discontinuation of the nitrofurantoin appears to lead to resolution of the lung problem.9 Cytotoxic drugs are thought to cause DILD in 1-10% of people. The commonest cardiovascular drug to cause problems is amiodarone, affecting as many as 6% of patients and with a significant mortality of 10-20%.

Some of the drugs associated with rheumatoid arthritis and inflammatory bowel disease are commonly linked to ILD and, in common with some other DILDs, there is a dilemma as to whether it is the drug or the underlying condition causing the problem: is methotrexate causing DILD or is this rheumatoid lung disease?

The likelihood of developing DILD is considered to be largely unpredictable and idiosyncratic. Drug toxicity is more common at the extremes of age and is linked to lower renal excretion, lower liver perfusion and overall metabolic function at these extremes.

Many types of DILD are described by their appearance on HRCT scanning:

- Non specific Interstitial Pneumonia (NSIP) – often shows patchy ‘ground glass’ opacities and consolidation in association with irregular reticular opacities in the peripheral and basal areas of the lung (this is common with amiodarone and methotrexate)

- Usual Interstitial Pneumonia (UIP) – is common with cytotoxic agents like methotrexate and bleomycin and is associated with scattered or diffuse areas of ground glass opacity and later with traction bronchiectasis and honeycombing.

- Hypersensitivity pneumonia (HSP) – is associated with sulphonamides and NSAIDs which often present with bilateral patchy ground glass opacities, often with upper lobe predominant centrilobar nodules. In chronic disease often a NSIP or UIP with fibrosis predominates.

- Bronchiolitis obliterans organizing pneumonia (BOOP) – often shows patchy ground glass opacities peripherally (particularly with minocycline, amiodarone and phenytoin).

So in summary, some drugs are associated with ILD and a few appear to cause ILD – commonly, amiodarone, methotrexate and nitrofurantoin. See Table 1.

Occupational

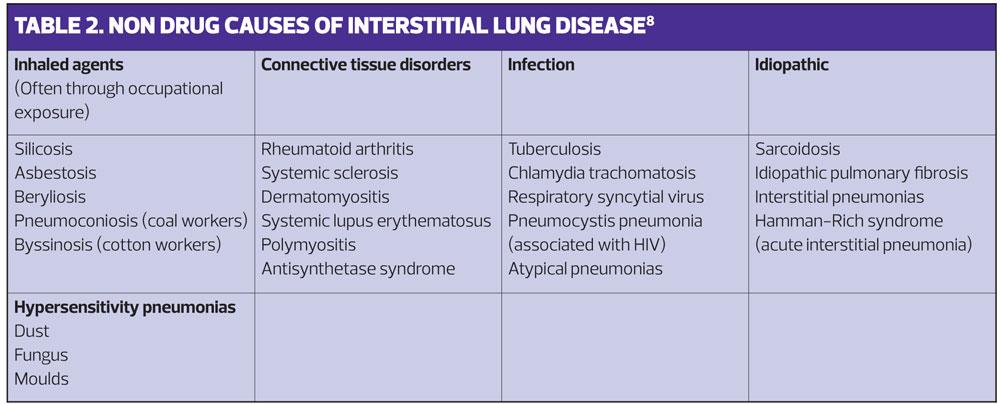

Some of the causes of ILD – the inhaled group in Table 2 – can be caused by occupation. A careful occupational history, and detail of what these occupations entailed, is therefore a vital part of the work up.

PREVALENCE

Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis (IPF) accounts for around 40 -50% of ILD in Europe.10 Prevalence ranges of 1.25 to 23.4 per 100,000, (annual incidence 0.22-7.4 per 100,000) for IPF are tending to be revised upward.10 A recent British Lung Foundation study found the UK prevalence of IPF was now 50 per 100,000, roughly twice the previous estimates.11 IPF incidence increases with age (100-400 per 100,000 of over-70s). Increases in life expectancy are therefore reflected in increased numbers of patients diagnosed with IPF.11 IPF will be covered in more detail in a subsequent article.

The recorded prevalence of other ILDs is also increasing. For example, the prevalence of sarcoidosis increased by nearly 8% between 2008 and 2012.12 The major ILDs of known aetiology, such as pneumoconiosis, hypersensitivity pneumonitis, iatrogenic ILD caused by drugs or radiation, and post infectious ILD are believed to be around 35% of all ILD cases.1 Reliable prevalence and incidence figures, however, are not available for many of the other, rarer ILD disorders; their rarity means that the population studies needed to establish prevalence and incidence are prohibitively difficult and there are no national registries.

WHEN WE SHOULD BE SUSPICIOUS

Symptoms

There are two common presenting symptoms, both of which are non-specific.

- Cough – often the most commonly described symptom, usually dry and annoying, but may be productive

- Shortness of breath (dyspnoea) – the second most common symptom, initially on exertion but often progressive.

However, cough and dyspnoea are common and can indicate other significant causes, both cardiac (e.g. heart failure; pleural effusion from a variety of causes) and other respiratory causes including COPD, asthma and lung cancer. It would be appropriate to undertake investigation for these urgently as an early diagnosis of lung cancer can significantly improve prognosis.

The majority of the long term management and surveillance of patients with respiratory conditions in primary care settings is now undertaken by general practice nurses. You should be prepared to consider ILD if a patient with a current respiratory diagnosis has increased symptoms or does not respond to treatment as expected. It is important to re-evaluate and seek a second opinion. Although these conditions are rare, rarities can and do occur, and you may be missing something.

Clinical history

The duration, severity and nature of the symptoms described should be clarified. If these appear to be causing significant problems, and no other cause is clear, it is sensible to think about the occupational history. Some occupations may be particularly relevant, e.g. building and ship building, where asbestos has been a problem, or involvement in cotton or silica based industries. Assessing exposure to smoking and to family pets (including pigeons) and animals at work is appropriate too.

The past medical history may give clues, especially rheumatoid-like processes or a history of atypical infection, as may the medication used. Some of the features may be difficult to associate with ILD, so it is very important to remain open minded and it is vital to take a complete and structured medical history so that things that may initially appear to be irrelevant to the respiratory history are not overlooked. For example, someone with dry eyes and dry mouth may have Sjorgen’s syndrome (an auto immune disorder linked to rheumatoid arthritis which usually affects women);13 similarly, someone with Raynaud’s syndrome, a very dry skin, or oesphageal reflux, may have systemic sclerosis or other connective tissue disease.

Clinical examination/signs

It is worth examining the hands with care, looking for finger clubbing and for evidence of rheumatoid arthritis. As with other causes of breathlessness or cough it is sensible to carefully examine the cardiorespiratory system and the throat, and to check for lymphadenopathy.

Tip: finger clubbing is not a feature in COPD but can be found in people with lung abscess, bronchiectasis, cancer and ILD, amongst others. A priority would be to exclude carcinoma of the lung.

Bi-basal crackles (especially persistent and often described as sounding like Velcro) are commonly found. However, if there is no clinically abnormal finding this does not exclude the diagnosis.

Investigations

Restrictive spirometry may be found, but the disease has to be relatively extensive for this to be the case, and other causes of restrictive lung disease, such as obesity, neuromuscular disease, carcinoma and pleural effusion, need to be considered. Indeed many people with ILD have normal spirometry.14

A normal chest X-ray does not exclude ILD as the changes may be subtle and other imaging, such as CT scanning will be needed.

Tip: A normal chest X-ray report does not exclude serious respiratory pathology. The presenting symptoms of lung cancer can be similar to those of ILD and urgent chest X-ray or referral should be considered.

Basic blood tests should be considered prior to referral:

- FBC and thyroid function – to exclude anaemia and thyroid disease, both of which can present with breathlessness

- Renal and liver function – necessary prior to the use of contrast in CT imaging and to exclude the renal and liver conditions that can cause fatigue and breathlessness

- Calcium level – hypocalcaemia can cause breathlessness due to muscle spasm and a raised level is associated with lung cancer and sarcoidosis. High levels can also trigger cardiac arrhythmias, complicating the picture of breathlessness

- Plasma viscosity and/or C reactive protein – to check for inflammation, as these may give vital clues as to the diagnosis.

Suspicion of rheumatoid or connective tissue disease should prompt appropriate testing too.

Epidemiological study indicates that many people have multimorbidity, especially as they age.15 Therefore, if there is a strong clinical suspicion of ILD, or the picture of another condition is atypical and the response to treatment is not as expected, it is sensible to consider more specialist referral, after basic testing.

MANAGEMENT

In England early referral to a specialist centre should result in appropriate investigations and a multidisciplinary team assessment. The benefits of this are manifold. The relative rarity of the diagnosis – and subtleties in diagnosis – mean that the average respiratory physician will often see relatively low numbers of people with any of the many ILD conditions. Centralising the process is anticipated to result in more accurate and timely diagnosis, and appropriate assessment for any specific treatment that may be available. In addition, newer drugs that can slow disease progression in some conditions (i.e. IPF) are expensive. The specialist team will be well placed to assess patients for these treatments.

However, there are some general management principles that are worth considering with every patient and that fall well within the remit of primary care

Smoking cessation

While many of the ILDs are not directly associated with smoking, bronchiolitis obliterans is clearly linked. However, respiratory bronchiolitis interstitial lung disease (RBILD) and bronchiolitis obliterans are associated with the inhalation of airborne diacetyl (DA) or acetyl proprionyl (AP). Bronchiolitis obliterans has also been associated with the same airborne chemicals that cause the occupational lung disease ‘popcorn lung’. This is linked to butterscotch flavourings and some e-cigarette vaping solutions. It should be noted that the level of DA and AP are generally three times higher in normal cigarettes compared to e-cigarettes.16

Smoking cessation interventions are well recognised to benefit many conditions and in ILD some therapeutic interventions, such as newer medicines and transplant referral, are often not considered unless the patient has stopped smoking.

On-going care

This will often be shared between the specialist centre and primary care. Good communication, to ensure that shared care arrangements for medications and monitoring are accurate, is important. Patients will go through a phase of uncertainty while tests are being performed, then a period of time trying to understand the diagnosis and treatment options and what they mean for themselves and their family and friends. During this phase an opportunity to discuss their ideas, concerns and expectations of treatment can make a lasting difference to the clinician-patient relationship.

Exercise

There is a growing body of evidence for the positive effects of early rehabilitation for those with an ILD, although the precise nature of the interventions is not yet well established.17,18 Encouraging activity within the constraints of their symptoms will enhance quality of life and improve exercise capacity, reducing muscle deconditioning and allowing patients to maximize their potential for physical activity.

Nutrition and weight management

Good nutrition will be important as cachexia similar to that seen in COPD and other long term conditions is often a factor. In patients treated with immunosuppressant agents, especially corticosteroids, weight gain can be problematic. For those individuals for whom transplantation is being considered a high body mass index would be a contraindication.

Oxygen

Early consideration of oxygen can be therapeutic for many. Ambulatory oxygen is often the first requirement. Oxygen saturations should be measured after walking as, in the early stages of many of the ILD processes, the resting saturations are normal. Oxygen assessment will normally be carried out by the specialist team.

Fatigue

As is common in many long term conditions fatigue is a feature of ILD, especially in sarcoid. Part of this is linked to the impact of breathlessness on the lung, and part linked to chronic systemic effects of inflammation elsewhere. It is important to check for treatable causes of fatigue such as thyroid disease, anaemia etc.

Education and information

The language and nature of ILD can be difficult to understand. The terminology can be confusing and the information on the Internet misleading and/or alarming. People with ILD, and their families, are frequently left feeling isolated, afraid and alone. We need to be able to understand the processes and prognosis so that we can explain it to our patients in a language they can understand.

The British Lung Foundation (BLF) is a good source of material in general, and specialist centres will usually provide patient information and information on any specialised medication. It can be common for the patient and family to eventually know more about the condition than their primary care clinicians so it is important that we listen and learn from them.19

Palliation and support

For some patients with ILD the disease is progressive and may lead to respiratory failure. Though some may benefit from lung transplantation quite a few will need symptomatic treatment. It is often useful to consider the thinking, breathing, functioning model as a way to help people with dyspneoa:20

- The thinking side encompasses people who may be anxious and raise their respiratory rate when they feel breathless, hence worsening symptoms. Though at times this may improve with low dose opiates or benzodiazepines, psychological support can also help.

- The breathing side encompasses areas of the disease process itself and physiotherapy for breathing exercises, or use of oxygen if hypoxic may help.

- Functioning – this often centres around considering how to encourage people to maximize their potential, with physiotherapy support to increase activity and reduce deconditioning.

If in doubt, involvement of palliative care specialists may well be an appropriate option to consider.

PROGNOSIS

For many of the ILD conditions the prognosis can be poor, with an inevitable deterioration and eventual death. However, several of these conditions will move into a quiescent phase or can be reversed (for example nitrofurantoin-induced ILD). The importance of an accurate specialist diagnosis, in order to consider the many causes and potential treatments that may help, is clear.

MAKING A DIFFERENCE

The ILD spectrum of diseases are relatively rare outside specialist practice, but thinking of these conditions in people who are left with symptoms for which there is not a clear diagnosis is important. The differential diagnosis is wide and though the diagnosis is often delayed a suspicion should warrant specialist referral. It is important to consider other causes, some of which need urgent referral, but with new specialist services the diagnosis is likely to be more accurate and give patients the best chances of successful treatment.

The diagnosis and treatment options are often complex but there is still a need to support the patient with symptomatic and other health needs. Working collaboratively with specialist colleagues will give our patients the best possible care. Though the diagnosis is rare, rapid and accurate diagnosis and appropriate treatment can make a difference.

ACTIVITY 1Access the health professional areas of the websites to increase your understanding of ILDBritish Lung Foundation https://www.blf.org.uk/ andAction for Pulmonary Fibrosis http://www.actionpulmonaryfibrosis.orgWhat patient information on these sites do you think might be useful in your practice?

ACTIVITY 2Do you have any patients with ILD on your practice database? Review their records.What was the period of time between the patient presenting with symptoms and receiving a diagnosis?Were any opportunities to make an earlier diagnosis missed?Are they under the care of a regional specialist team?Consider the role that your team could take in supporting these patients and their families.

LEARNING POINTSILDs affect the interstitium (tissue) of the lung and will include one or more of:– Fibrosis– Inflammation– Granulation.Classification of the various disease processes is based on these effects.The potential cause are often unknown (idiopathic) but may include:– Inhaled agents– Drugs– Connective tissue disorders– Infections– Malignancy.IPF accounts for 40-50% of the cases of ILD. The prevalence of ILDs is increasing, and is probably related to the rising age of the population.The list of drugs that can cause drug-induced ILD is long, but the common culprits are amiodarone, methotrexate and nitrofurantoin.The common symptoms of ILD, cough (usually dry and annoying) and progressive dyspnea, are non-specific.ILD should be considered as part of the differential diagnosis in any patient for whom there is no clear diagnosis and in patients with a current respiratory diagnosis who are worsening and/or are not responding to treatment as expected.Appropriate early referral to the specialist team will help ensure early, accurate diagnosis, appropriate treatment and the best possible outcome.Prior to referral for specialist investigation some routine investigations, to exclude alternative causes for the symptoms, should be carried out.Some general management principles (smoking cessation, exercise, nutrition etc.) can be applied and reinforced in a primary care setting.

REFERENCES

1. European Respiratory Society. EUROPEAN LUNG white book. 2017. https://www.erswhitebook.org/

2. Sweidan AJ, Singh NK, Dang N, Lam V, Datta J. Amiodarone- induced pulmonary toxicity – a frequently missed complication. Clinical Medicine Insights: Case Reports 2016; 9; 91-94

3. Thicket DR, Kendall C, Spencer LG et al. Improving care for patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) in the UK: a round table discussion. Thorax 2014; 69: 1136-1140

4. NHS England. Interstitial Lung Disease (Adults) Service Specification 19th June 2017. London England. https://www.england.nhs.uk/publication/interstitial-lung-disease-adults-service-specification/

5. Zibrak JD, Price D. Interstitial lung disease: raising the index of suspicion in primary care. NPJ Primary Care Respiratory Medicine 2014;24:14054 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4373409/

6. Raghu G, Rochwerg B, Zhang Y et al. An Official ATS/ERS/JRS/ALAT Clinical Practice Guideline: Treatment of Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis. An update of the 2011 clinical practice guideline. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine 2015; 192(2):e3-19

7. Scullion J, Holmes S. The curious case of sarcoidosis. Independent Nurse. 2016; (6):20-2 http://www.independentnurse.co.uk/clinical-article/the-curious-case-of-sarcoidosis/117312/

8. Scullion J, Holmes S. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Independent Nurse. 2016;2016(15):20-2. http://www.independentnurse.co.uk/clinical-article/idiopathic-pulmonary-fibrosis/145708/

9. Marshall ADL, Dempsey OJ. Is “nitrofurantoin lung”on the increase? BMJ 2013; 346. doi: https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.f3897

10. Nalysnyk L, Cid-Ruzafa J,m Roteller P, Essere D 2012, Incidence and prevalence of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: review of the literature. European Respiratory Review 2012 21:355-361; DOI: 10.1183/09059180.00002512

11. British Lung Foundation 2017 Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis statistics. https://statistics.blf.org.uk/pulmonary-fibrosis

12. British Lung Foundation 2017 Sarcoidosis https://statistics.blf.org.uk/sarcoidosis

13. Borchers AT, Naguwa SM, Keen CL, Gershwin ME. Immunopathogenesis of Sjögren's syndrome. Clinical Reviews in Allergy & Immunology. 2003;25(1):89-104

14. Aaron SD, Dales RE, Cardinal P. 1999. How accurate is spirometry at predicting restrictive pulmonary impairment? Chest 1999; 115930: 869-873.

15. Barnett K, Mercer SW, Norbury M et al. Epidemiology of multimorbidity and implications for health care, research, and medical education: a cross-sectional study. The Lancet. 2012; 380(9836): 37-43

16. Kreiss K, Gomaa A, Kullman G et al. Clinical bronchiolitis obliterans in workers at a microwave-popcorn plant. New England Journal of Medicine 2002; 347: 330-338.

17. Wells A, Hirani N. Interstitial lung disease guideline: the British Thoracic Society in collaboration with the Thoracic Society of Australia and New Zealand and the Irish Thoracic Society. Thorax 2008; 63(Suppl V):v1–v58.

18. NICE. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis in adults: diagnosis and management. 2013 CG163 https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg163

19. Scullion JE, Holmes S. Interstitial Lung Disease. Independent Nurse 2014; 16: 31-35 http://www.independentnurse.co.uk/clinical-article/diagnosing-and-treating-interstitial-lung-disease/65090/

20. Spathis A, Booth S, Moffat C et al. 2017. The Breathing, Thinking, Functioning clinical model: a proposal to facilitate evidence-based breathlessness management in chronic respiratory disease. npj Primary Care Respiratory Medicine 2017 Article 27. doi:10.1038/s41533-017-0024-z

Related articles

View all Articles