Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis

JANE SCULLION

JANE SCULLION

MSc, BA(Hons), RGN.

Nurse consultant, University Hospitals of Leicester. Trustee Education for Health

STEVE HOLMES

MMedSci, MBChB, FRCGP, DRCOG. General Practitioner, The Park Medical Practice, Shepton Mallet, Somerset. Trustee, Education for Health

IPF is one of the most common of the interstitial lung diseases, as discussed in our January issue, and often co-exists with COPD and other long term comorbidities. However, missed or inaccurate diagnoses mean its prevalence may be underestimated

LEARNING OUTCOMES

After working through this article you will be able to:

- Describe the symptoms that should trigger consideration of IPF

- Discuss the prevalence of IPF and the tests and process for making a diagnosis

- Describe the benefits, side effects and potential monitoring and interactions associated with pharmacological treatments for IPF

- Describe the non-pharmacological interventions that should be considered in IPF.

Of all the Interstitial Lung Diseases (ILD) one of the most common is Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis (IPF).1 IPF is a chronic, progressive condition of unknown origin characterised by shortness of breath, diffuse infiltrates on chest X-ray (CXR), inflammation and/or fibrosis on biopsy. It principally affects the alveoli, inhibiting oxygen transfer. In addition to dyspnoea, symptoms include dry cough and fatigue. Over time, symptoms are associated with a decline in lung function, reduced quality of life, and ultimately, death.2

In our previous article,1 we stated that IPF accounts for around 40-50% of the cases of ILD.3 This is in part due to the rising age of the population, as the incidence rises with age, but also to the lower threshold we have for using high resolution computed tomography (HRCT) – with the result that we find more when we look for it. There is also a rising public profile due to the recent death of Keith Chegwin and the revelation that Katie Price’s mother has IPF. The UK prevalence of IPF is around 50 per 100,000. However, as with many respiratory disorders, this figure is likely to be inaccurate due to missed or wrong diagnoses.4

In common with many other diseases NICE has issued guidance for the diagnosis and management of IPF.5 While our index for suspicion of IPF is similar to that of the other ILDs, NICE advises that we should think about the possibility in people aged over 45 years presenting with:

- Persistent breathlessness on exertion

- Persistent cough

- Bilateral inspiratory crackles when listening to the chest

- Clubbing of the fingers

- Normal, or impaired spirometry – usually with a restrictive pattern but sometimes with an obstructive pattern.

NICE also states that we should consider a chest X-ray (CXR) or referral to a specialist if we have concerns.5

It is vital to remember that clubbing may not be present in early disease and a normal CXR, as with many other conditions, does not exclude IPF. Indeed, several of these symptoms should make clinicians think about other diagnoses, some of which need rapid diagnosis, notably lung cancer.

In clinical practice, people who smoke and those with Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD) are seen much more commonly than people with IPF. In addition, around two thirds of people with IPF are smokers and IPF often co-exists with COPD and other co-morbidities such as cardiac disease. It is therefore very important that we keep an open mind if we are not to miss this rarer diagnosis.

DIAGNOSIS

An accurate and timely diagnosis is vital for IPF as there are now medications available that can slow disease progression.

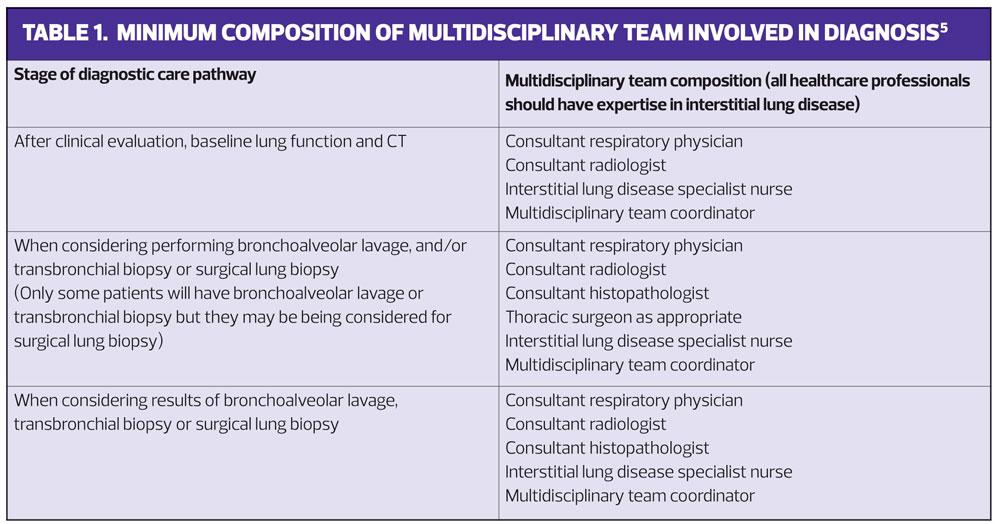

The diagnosis should be confirmed in a specialist centre where the required multidisciplinary consensus can be obtained, (See Table 1) and where further tests, such as bronchoalveolar lavage or transbronchial biopsy and/or surgical lung biopsy, can be carried out if a confident diagnosis cannot be made without them.5

The diagnosis of IPF is made through:

- Detailed history taking

- Thorough clinical examination

- Blood tests

- CXR

- Lung function testing (both spirometry and gas transfer)

- High resolution CT scan.

This initial work up can help to exclude alternative diagnoses, including non-lung diseases and lung diseases associated with environmental and occupational exposure, connective tissue diseases and drug effects. (See Interstitial Lung Disease, Practice Nurse January 2018).5 It will ensure that those that are left truly have an idiopathic picture, and possibly identify co-existing morbidities which may complicate both the diagnosis and any proposed treatment.

As with all diseases it is important to have open and honest discussions with patients and their families about the risks and benefits of a certain or uncertain diagnosis, and the risks and benefits of any procedures or treatments. If there is no consensus on the diagnosis then a ‘watch and wait’ approach, under specialist supervision, is advocated. At all stages of the disease accurate and detailed information should be given, and repeated as necessary.

PHARMACOTHERAPY

Prior to 2012 evidence for the treatment of IPF was lacking, although people were often prescribed a combination of N-acetylcysteine (NAC), prednisolone and azathioprine; so called triple therapy. However, the PANTHER-IPF trial,6 which was stopped early, showed that this treatment was not useful in maintenance therapy for IPF and, indeed, significantly increased both mortality and the number of hospital admissions.

The antifibrotics

Currently there are two licensed antifibrotics for IPF – pirfenidone and nintedanib – neither of which are curative, although both are believed to slow down disease progression. Both require regular blood monitoring for hepatotoxicity. It is important to understand how these drugs work, their side effects and contraindications.

Pirfenidone

This was the first licensed antifibrotic treatment for IPF (licensed in 2011). It is an oral treatment that, in clinical trials, has been found to slow disease progression.7 In the trials this appeared to produce a relative reduction in loss of the forced vital capacity (FVC) and a combined analysis demonstrated a reduction in all-cause mortality at 1 year.

Photosensitivity is likely with pirfenidone (9.3%). Before commencing treatment patients should be advised to wear sun protection factor 50 cream when outside, even in British sunshine. The other common side effects of pirfenidone are mainly gastrointestinal (GI), especially nausea (32.4%), diarrhoea (18.8%), and dyspepsia (16.1%).

Prior to commencing treatment, it is appropriate to check renal and liver function and regular, monthly liver function tests are necessary whilst on treatment. It is anticipated that between 1-10% of patients will develop abnormal liver function.

Pirfenidone is relatively contraindicated in smokers. In the early trials smokers who took perfenidone were likely to get only half the amount of drug. Patients can be supported with smoking cessation by referral to appropriate services.

The side effects of anorexia, angioedema, dizziness, fatigue and weight loss are also common and can be distressing for patients. It is advised to take pirfenidone with a full meal, which may be difficult for people with a reduced appetite. Patients should also avoid grapefruit and grapefruit juice as 70–80% of pirfenidone is metabolised via CYP1A2 system enzymes.

CYP1A2 enzymes are involved in the metabolism of many drugs, thus affecting total drug dosage, as well as in the synthesis of cholesterol, steroids and other lipids. Several medications metabolised via the CYP1A2 pathway, such as amiodarone, ciprofloxacin, fluconazole and fluvoxamine, reduce pirfenidone clearance and hence increase the risk of toxic levels by a factor of 2–4, unless dose adjustments are made. This will require a careful assessment of the individual patient and the risks/benefits of the options in order to determine which drugs/doses to change.

Detailed information on prescribing and side effects is available from the Electronic Medicines Compendium (eMC), https:// www.medicines.org.uk/emc/medicine/29932

Nintedanib

The biologic agent, nintedanib, is an inhibitor of tyrosine kinase and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF). More commonly used in the treatment of non small cell lung cancer (adenocarcinoma), nintedanib has been used in IPF since early 2015, and it too appears to slow down disease progression. Again detailed information is available from EMC, https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/medicine/29790

The trials for nintedanib showed a reduction in loss of FVC compared to placebo of around 110mls per year, with 53% of those treated responding. These trials did not however show a significant improvement in health-related quality of life (hence not a great clinically noticeable improvement) and though there was a numerical reduction in exacerbations during the trial period this was not statistically significant.8

The side effects with nintedanib are mainly lower GI, of which diarrhoea is the most common (62.4%). In most patients, the diarrhoea is mild to moderate and will reduce after three months of treatment, although around 5% of patients discontinued nintedanib because of diarrhoea. Abdominal pain and decreased appetite is also very common, affecting more than 10% of patients. Abnormal liver function tests were found in 13.4% of people given the drug. Bleeding, usually epistaxis, was also common, affecting 1-10% of patients. Adverse effects are generally manageable in most patients through dose reduction, treatment interruptions and management of symptoms.

There are a number of cautions around recognised risks with this category of drug, although these were not identified as significant risks in trials of this specific agent. There is a risk of bowel perforation and caution therefore needs to be exercised in people with a history of peptic ulceration, diverticular disease or who are concurrently using steroids or anti-inflammatory drugs. There is also an increased potential risk of deep vein thrombosis and, similarly, a risk of QT prolongation, although the latter has not been demonstrated in research.

In common with other biologic agents, nintedanib is associated with significant risks to people with soya or peanut allergy where severe anaphylaxis has been noted.

PRESCRIBING RESTRICTIONS

Both pirfenidone and nintedanib have very strict prescribing criteria under NICE recommendations.7,8 Both of these drugs can only be prescribed through specialist centres after a multidisciplinary team review. Their authorisation for funding is dependent on a FVC of between 50-80% predicted. It may be hard to explain to people with a higher FVC (often artificially so because of co-existent emphysema) that they need to get worse before they can have a treatment that slows down disease progression. Similarly, it might be hard to explain to patients whose lung function is worse than this that they too are ineligible for a treatment to slow their rate of deterioration.

If people are intolerant of one medication then they may be offered the other, providing they meet the entry criteria, and there are many centres that offer access to clinical trials that people may wish to try.

NON PHARMACOLOGICAL THERAPY

Pulmonary rehabilitation (PR)

Exercise is important for all people with lung disease. PR is advocated by NICE although it is not certain which aspects of current programmes fit the needs of people with IPF. NICE suggests that PR programmes are individually tailored to the needs of people with IPF.5

What PR does appear to help with is the management of breathlessness and it gives the patients a sense that they are doing something to help their condition. Assessment, which should include a 6-minute walk and a validated quality of life assessment, is recommended at diagnosis and at 6-month and 12-month intervals.5

Best supportive care

Best supportive care is recommended from the point of diagnosis.4 It should be tailored to disease severity, rate of progression, and the patient's preferences, ideas, concerns and expectations and should include, if appropriate:

- Information and support

- Symptom relief

- Management of comorbidities

- Withdrawal of therapies suspected of being ineffective or causing harm

- End of life (EOL) care.5

There is no cure for IPF at present. In studies, a prognosis of around 3-5-year survival from diagnosis is common. What we don’t know is how long people have had the disease before they present for diagnosis so this survival prognosis may be skewed, and progression varies greatly from person to person. Some patients progress rapidly from the time of diagnosis, some can have relative stability over a prolonged period of time, some can have a substantial period of disease stability followed by an accelerated disease course, and some experience an unpredictable acute exacerbation of IPF (AE-IPF) that can lead rapidly to death.

While respiratory failure, which can be distressing, is the usual cause of death a substantial number of patients succumb to other causes, including complications of coronary artery disease, pulmonary embolism, pneumonia, pulmonary hypertension and lung cancer. Appropriate referral for palliative care services should be offered as appropriate and in most areas this should include symptom control, psychospiritual support and social input.

Primary care is often best placed to support people with advance care planning. EOL care, to be successful, will depend on good co-ordination and communication across boundaries.

Symptom control

Symptom control is important throughout the patient pathway. Breathlessness is often a presenting factor with IPF and the person should be assessed for the underlying cause or causes of their breathlessness. It is worth assessing for hypoxia both on exertion and at rest. Commonly people with IPF have a normal oxygen level at rest but this can drop significantly on even minimal exertions. There are a variety of options for treating hypoxia (long term oxygen or short burst alternatives, or in combination). There are also symptomatic treatments for breathlessness such as low dose opiate or benzodiazepines.5

Cough can also be troublesome and we should look for causes that might be amenable to treatment, such as gastro-oesophageal reflux disease and post-nasal drip.5 Some specialist centres are considering thalidomide treatment for cough in this situation.5

Diet

All advanced diseases can cause weight loss and are generally a predictor of a poor prognosis. Additionally, in IPF the side effects of medication, breathlessness, dry mouth, cough and increased metabolism due to the work of breathing, may contribute to problems with diet and weight loss. Consider offering nutritional supplements to patients who are malnourished.

Transplant

Transplant is an option for some patients although comorbidity often excludes others. Decisions about transplant are difficult for patients and their carers to make, and support and discussion are important in a complex decision with significant risks.

Patient support

Patient support is important and should include practical advice, such as advice on working, benefits available and social support agencies. As in many chronic diseases, the true disability people experience is often hidden, and other people may be quick to make erroneous judgements about their general health and work capacity.

There are local, regional and national groups that support people with IPF and their carers. Groups are important in helping the person with IPF, family and friends to understand what is a relatively rare disease, and to campaign for and raise the profile of it.

EXACERBATIONS

Acute exacerbations of IPF (AE-IPF) are defined as a sudden acceleration of the disease or as an idiopathic acute injury superimposed on an already diseased lung. Both lead to a significant decline in lung function.8 In the literature, a true AE-IPF is associated with a very high mortality rate of around 85%, with mean survival periods of 3 to 13 days,9,10 although some people have many less severe flare ups prior to their ultimate demise. It is therefore important to distinguish AE-IPF from conditions that may mimic its presentation.8 Clinically this means considering alternative diagnoses like infection, pulmonary embolism, pneumothorax, heart failure and atrial fibrillation. An AE-IPF should be considered if there is unexplained dyspnoea within 30 days and new bilateral ground-glass abnormality and/or consolidation compared with previous HRCT.

The most appropriate treatment of an acute exacerbation is still not known. Supportive measures such as supplemental oxygen, relief of dyspnoea and psychological support will be important. Typically, treatment of AE-IPF has been similar to treatment for exacerbations of COPD, i.e. with steroids and antibiotics, although this remains unproven and controversial.

CONCLUSION

IPF can be a devastating disease but, as NICE suggests in its guidance, we should aim to improve the quality of life for people with this condition by supporting specialist healthcare professionals to diagnose the condition early and provide effective symptom management.

Clinicians in primary care, as the gatekeepers to services, have a pivotal role in detecting IPF as early as is feasible. As the healthcare professionals who often have the privilege of long-term relationships with patients, and their families, we are in a prime position to support patients through their journey and to liaise with specialist care and supporting agencies to ensure high quality continuity of care.

LEARNING POINTS

- IPF is the commonest form of ILD.

- IPF has a prevalence of around 50/100,000.

- Diagnosis should be made by a specialist multidisciplinary team.

- There are two pharmacological preparations that have specific indications for IPF and are finding use in people with IPF (pirfenidone and nintedanib).

- Good care incorporates psychosocial support, symptomatic treatment and good communication.

ACTIVITY 1Increase your understanding of IPF and the role of nintedanib in its management by reading Clinical use of nintedanib in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, by Amy Hajari Case and Peace Johnson, in BMJ Open Respiratory Research 2017;4:3000192 http://bmjopenrespres.bmj.com/content/4/1/e000192

ACTIVITY 2Look up the NICE technology appraisals for nintedanib (TA379) and pirfenidone (TA282]. How do the evidence and costs for each treatment option compare?https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ta379/chapter/1-Recommendationshttps://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ta282

ACTIVITY 3Visit the ‘Living with PF’ pages at Action for Pulmonary Fibrosis http://www.actionpulmonaryfibrosis.org . What aspects of this advice could you incorporate into your support for patients with IPF? In particular, read the section Hoping for the best, planning for the worst. Would this help you with any patient facing a terminal illness?

RESOURCESInformation and support for patients and healthcare professionalsBritish Lung Foundation https://www.blf.org.uk/Action for Pulmonary Fibrosis http://www.actionpulmonaryfibrosis.org Education, information and training for healthcare professionalsEducation for Health https://www.educationforhealth.orgPrimary Care Respiratory Society UK https://pcrs-uk.org/

REFERENCES

1. Scullion J, Holmes S. Interstitial Lung Disease. Practice Nurse 2018;48(1):22–28

2. NICE CG163. Ideopathic pulmonary fibrosis in adults: diagnosis and management, 2013 (updated May 2017).https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg163

3. European Respiratory Society. EUROPEAN LUNG white book. 2017. https://www.erswhitebook.org/

4. British Lung Foundation. Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis statistics. 2017 https://statistics.blf.org.uk/pulmonary-fibrosis

5. NICE Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis in adults: diagnosis and management. Clinical guideline [CG163]: June 2013 Last updated: May 2017 https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg163

6. The Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis Clinical Research Network. Prednisone, Azathioprine, and N-Acetylcysteine for Pulmonary Fibrosis. N Engl J Med 2012; 366:1968-1977 May 24, 2012 DOI: 10.1056/NEJMoa1113354 http://www.nejm.org/toc/nejm/366/21/

7. NICE TA282. Pirfenidone for treating idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, April 2013. http://guidance.nice.org.uk/ta282

8. NICE TA379. Nintedanib for treating idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. January 2016. http://guidance.nice.org.uk/ta379

9. Collard HR, Moore BB, Flaherty KR, et al Acute exacerbations of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine 2007;176:636-43

10. Juarez MM, Chan AL, Norris AG. Acute exacerbation of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis – a review of current and novel pharmacotherapies. Journal of Thoracic Diseases 2015;7(3):499-519

Related articles

View all Articles