Greener Respiratory Healthcare: A Call To Action

Rhian Last

Rhian Last

Nurse Educator

Course Tutor with Rotherham Respiratory Ltd

Sponsor for Leeds BAME Primary Care Network

RCGP Yorkshire Faculty Board Member

Self Care Forum Faculty Board Member and Trustee

Practice Nurse 2021;51(1):17-21

With everything that has happened over the last 12 months – and with continuing, soaring, COVID-19 infection and death rates – it is easy to lose sight of another global threat: the climate emergency. Here we examine what GPNs can do to contribute to ‘greener’ healthcare

The COVID-19 pandemic has posed many challenges to the way that the NHS and general practice deliver healthcare but has also shown that radical changes, many of which are kinder to the environment, can be made and can actually improve the patient experience.

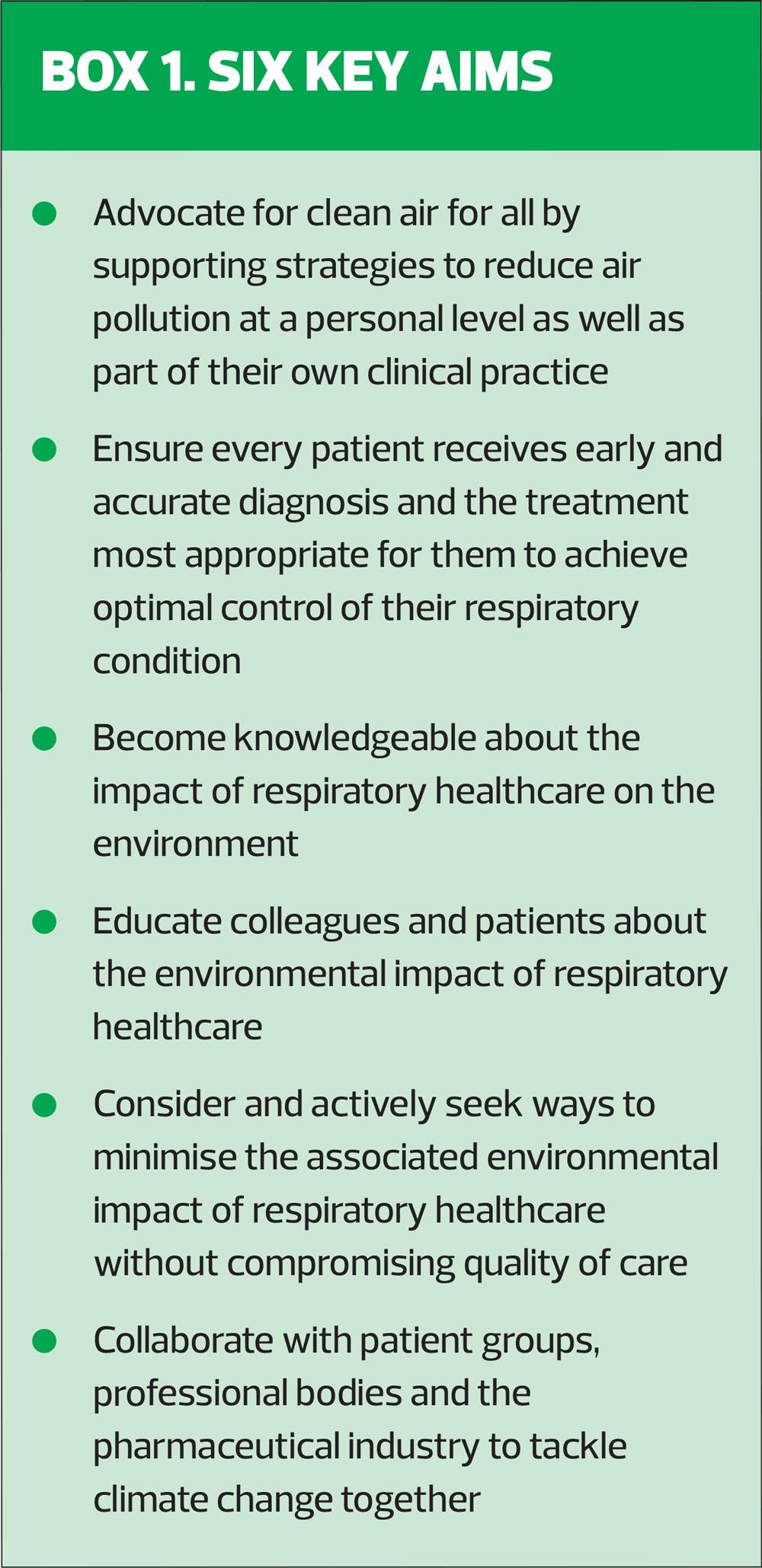

This is one of the key messages to emerge from a White Paper published towards the end of 2020 by the Primary Care Respiratory Society, in which the organisation calls for individual healthcare professionals, commissioners, professional organisations and the pharmaceutical industry to work together to make respiratory healthcare greener and more environmentally-friendly.1

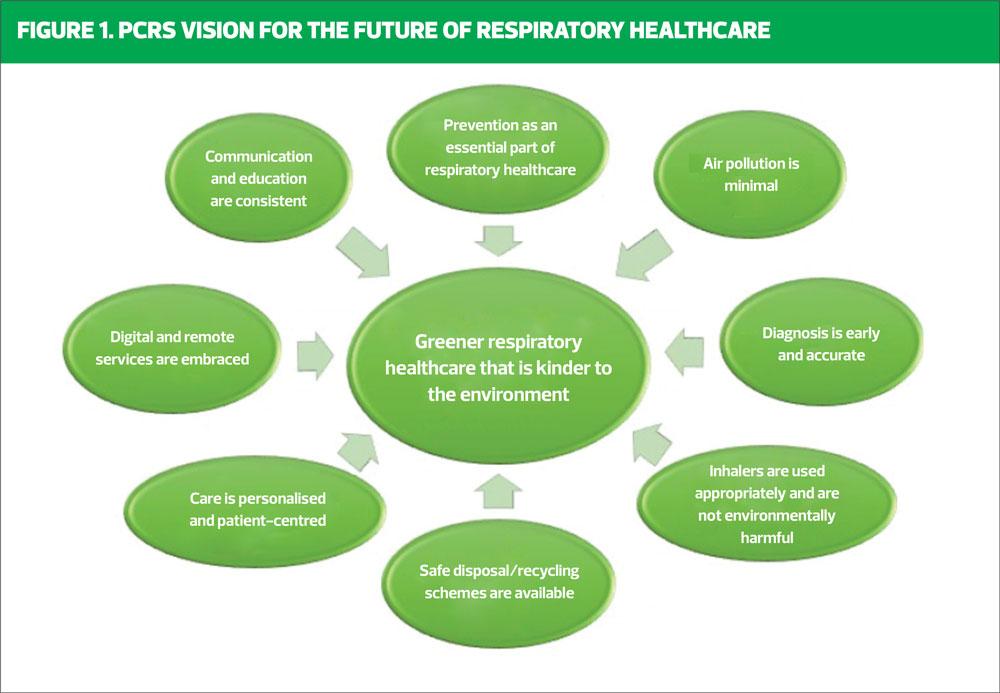

The overarching philosophy behind the PCRS vision (Figure 1) is one of ‘no waste, no harm.’

BACKGROUND

The PCRS highlights the increasing focus in recent years on the impact of the environment on human health and on the impact of the practice of medicine on the environment, both of which are relevant to respiratory medicine.

The Climate Change Act was first introduced in 2008 to ensure the UK cuts its carbon dioxide equivalent emissions by 80% by 2050 against a 1990 baseline.2 The interim targets for reductions in carbon dioxide equivalent emissions to meet the Climate Change Act were a 34% reduction by 2020 and a 50% reduction by 2025.

The NHS is responsible for 6.3% of England’s total carbon emissions and for 5% of all road traffic in the UK,3 and the UK is regarded as a major emitter with regard to healthcare-related emissions.

Between 28,000 and 36,000 deaths in the UK are thought to be attributable to human-made air pollution.1 In December 2020, in a landmark ruling, a coroner said failure to reduce pollution levels to legal limits was a material factor in the death of nine-year-old Ella Kissi-Debrah, who had severe asthma.

CURRENT RESPIRATORY PRACTICE

Greener respiratory healthcare is only one approach to reducing our carbon footprint, but it has the potential for significant impact. Sometimes when we are faced with a large scale problem that is complex and deep rooted there is a tendency to seek complicated over-arching solutions. This can cause hesitancy, delay, a reluctance to take ‘ownership’ and outcomes are not easy to measure. But there are individual issues that we can recognise and, as far as it is within our power, address.

Research has shown that asthma is commonly misdiagnosed. Overdiagnosis can result in unnecessary treatment and a delay in differential diagnosis. Underdiagnosis can compound daily symptoms, exacerbations and long term airway remodelling.4

Similarly, over a million people have been diagnosed with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) in the UK. In all probability there may be twice as many who remain undiagnosed. However, overdiagnosis can also be an issue.5

Early and accurate diagnosis avoids travel to unnecessary appointments and treatment with unnecessary medication, all at a cost to the patient’s health and wellbeing, to the NHS1 and additionally to the environment, something we don’t necessarily always consider.

Achieving optimal care is better for the patient, more cost effective for the NHS and will also have a positive impact on the environment through, for example, less treatment waste, reduced need for frequent appointments and less emergency presentations.

In order to ensure best practice that is evidence-based and safe it is essential that healthcare professionals are appropriately educated and trained and that this education is updated on a regular basis.

GREENER INHALERS

Research has shown that switching to inhalers with lower global warming potential could result in significant carbon savings – equivalent to installing wall insulation or cutting meat from our diets.6

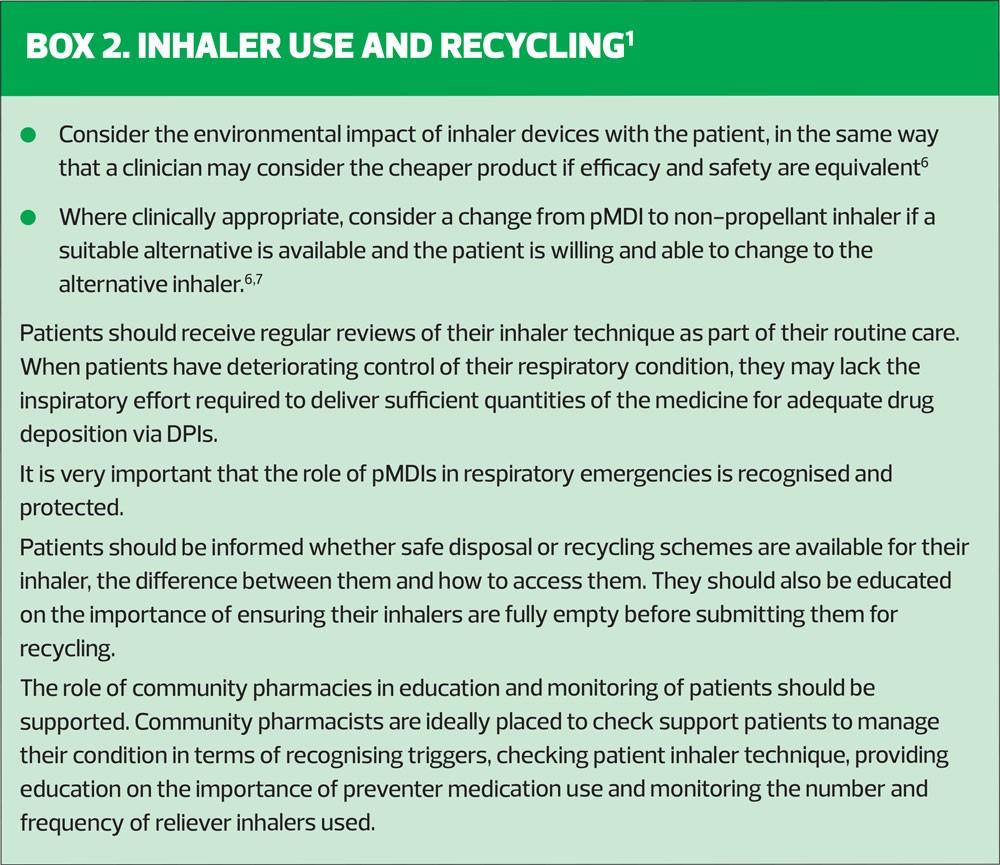

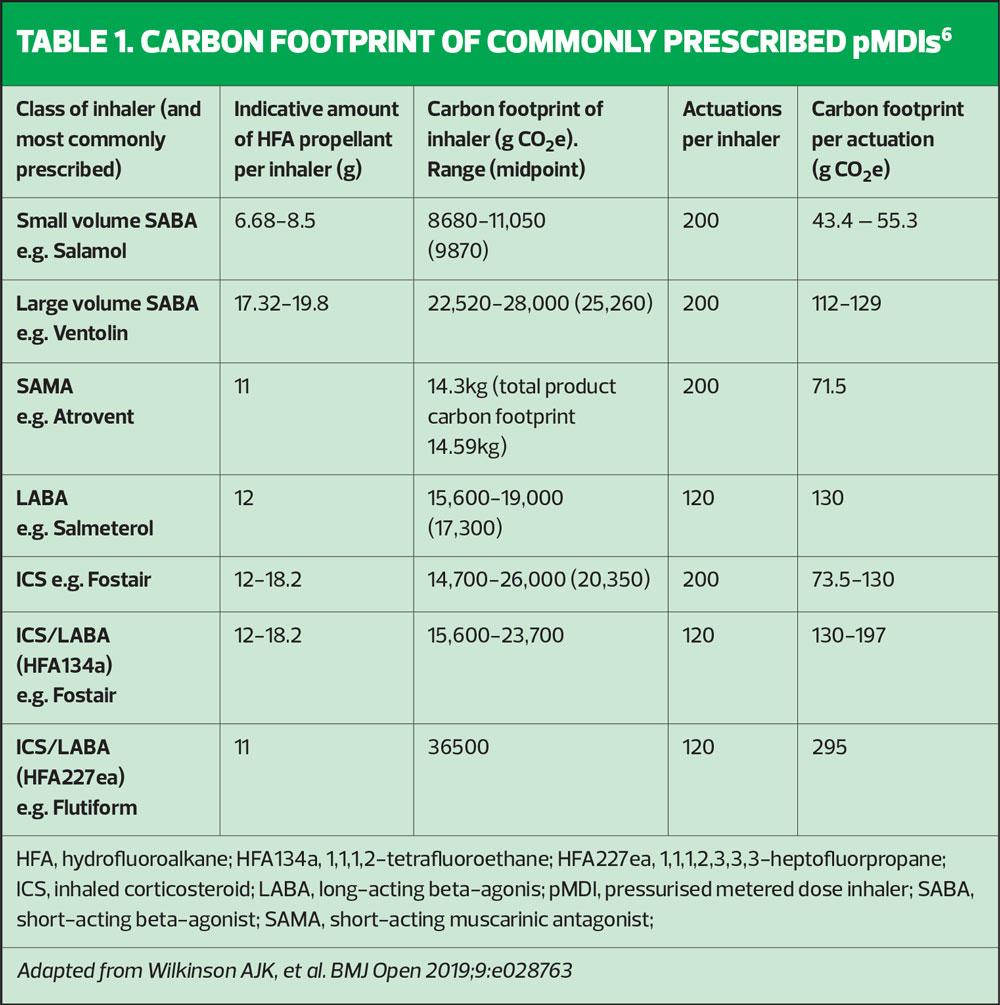

Pressurised metered dose inhalers (pMDIs) contain propellants that are potent greenhouse gases. Although chlorofluorcarbons (CFCs) were banned under the Montreal Protocol in 1987, they have been replaced with hydrofluoalkane (HFA) propellants, which are still considered to have significant global warming potential. Currently, pMDIs contribute to an estimated 3.9% of the carbon footprint of the NHS.

For every 10% of HFA pMDIs switched to devices with low global warming potential, 58 kt CO2e could be saved each year.6

There is a substantial difference in the carbon footprints of pMDIs: for example, Ventolin has a carbon footprint of over 25kg CO2e per inhaler, compared with Salamol, with less than 10kg CO2e. Dry powder inhalers (DPIs) and aqueous mist inhalers do not contain any HFAs.

Authors of the study, published in BMJ Open, say switching to DPIs, or small volume HFA MDIs instead of high volume HFA inhalers could achieve substantial carbon savings (Table 1).

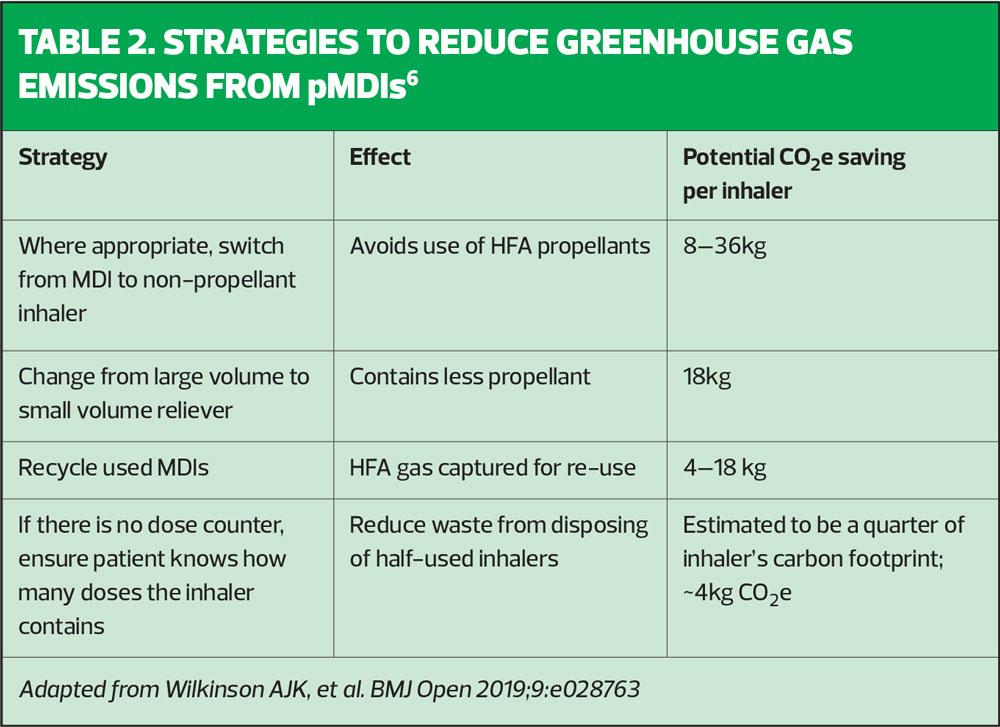

However, switching to a more environmentally friendly inhaler should be undertaken with care and deliberation and the absolute deciding factor will be that the patient can demonstrate a sound inhaler technique. Where it is determined that the most appropriate device for the individual patient remains a pMDI, there are strategies to reduce their environmental impact (Table 2).6 The PCRS also offers a number of points to consider in regard to inhaler device use and recycling (Box 2).1

Caution!

When making changes in practice, it is very important to be aware of unintended consequences. These can often be overlooked.8 Quick wins, sometimes referred to as low hanging fruit, can seem appealing but they can also come with safety and sustainability issues. For example, large scale inhaler device ‘switching’ from pMDIs to DPIs can easily be arranged via GP IT prescribing systems. But this is dangerous practice and according to the PCRS, it must be avoided.9 We should not be looking for quick wins but for safe, sustainable practice on a personalised and patient-centred basis.

When introducing patients to the concept of greener inhalers, by providing them with information, involving them in decision making and personalising their care, ensuring a sound inhaler technique and developing a robust supported self-management plan,10 we can address greener issues at the same time as we facilitate improved confidence, better adherence and optimal control.

The NICE decision aid, Inhalers for asthma, includes information on greener inhalers.7 Using this patient decision aid during consultation with your patients will aid informed choice and shared decision making when initiating inhaler treatment or considering a change of inhaler device.

Disposal

Patients should be encouraged to ensure that their inhalers are completely used up before disposal to avoid unnecessary waste. Although some inhalers are recyclable this is not always the case. Careful disposal is advised for all inhalers. Patients can be advised to take all spent inhalers to their pharmacist who can then assign them for recycling where appropriate, or consign them for safe disposal.

RELEVANCE TO GENERAL PRACTICE NURSES

The PCRS white paper provides valuable information on both the impact of the environment on respiratory conditions and the impact of respiratory healthcare on the environment, and provides useful sources of further information.

GPNs can raise awareness of the PCRS White Paper in their GP teams by bringing it to the agenda of a practice meeting and by sharing the link to the document with colleagues either by email or on the Practice intranet to spark some discussion.

They can also raise awareness of ‘Greener Practice’ with patients via the practice website, poster campaigns, during patient group consultations and, importantly, one conversation at a time. There is a wealth of information available from the Royal College of General Practitioners to support greener GP practice: https://www.rcgp.org.uk/policy/rcgp-policy-areas/climate-change-sustainable-development-and-health.aspx

While improvements that address greener respiratory care and that are aligned to evidence-based practice have real value at patient/practitioner level, it is through system-wide recognition, dissemination and implementation that powerful and sustainable impact can be achieved. What is happening in GP Federations, Primary Care Networks (PCNs) and within your local community to address carbon footprint reduction? Does your PCN have a local champion to support reducing carbon footprint reduction? Would that be useful? Is this addressed in your local Sustainability and Transformation Partnership (STP)? In some areas STPs have evolved to become Integrated Care Systems (ICSs) You can find out more about your particular locality here: https://www.england.nhs.uk/integratedcare/stps/view-stps/

Is there any mention in their information and plan about reducing carbon footprint? If so, what does it tell you? If not, do you think this an omission that needs addressing? Discuss this with your work colleagues and raise this with your local GPN Lead and your PCN Clinical Director. You could share the PCRS White Paper to start the conversation.

Taking personal stock of your own impact on the environment can be a valuable starting point. There are on line tools available and the findings can be insightful and maybe even surprising – try the WWF environmental footprint calculator at https://footprint.wwf.org.uk or the Carbon Footprint Calculator For Individuals And Households http://www.carbonfootprint.com/calculator.aspx

COVID-19

As we are all aware, we remain in the throes of a pandemic. We should take stock of the ways the pandemic has already shifted us to ways of working that are greener. We are making excellent adaptations by adopting digital technology for remote consultations, messaging patients, arranging repeat prescriptions etc., all reducing the need for travel. This will have a positive impact on our local environment. We need to identify what is working well and harness it so it doesn’t get lost post-pandemic. However, it is also important to recognise that virtual consultations may not be suitable for every patient, and for patients who are digitally inexperienced – or simply don’t have Internet access – other, more conventional approaches will still be needed.

We are currently engaged in a mass vaccination programme as well as juggling with the provision of usual primary care services. These are challenging times! This does mean that engaging hearts and minds to embark on improvement initiatives to support greener respiratory healthcare will be difficult. However, now can be a good time to sow seeds and spark conversations and to perhaps start outlining a plan of action so that when we move out of the pandemic we can move forward with greater determination to address greener practice.

KEY POINTS

The PCRS White Paper presents a call to action that GPNs and their practices can respond to in order to make meaningful changes that will lead to greener respiratory healthcare and improved patient outcomes, by ensuring that:

- Prevention is an essential part of respiratory healthcare

- Air pollution is minimal

- Diagnosis is early and accurate

- Inhalers are used appropriately and are not environmentally harmful

- Safe inhaler disposal/recycling schemes are available

- Care is personalised and patient-centred

- Digital and remote service are embraced (where appropriate)

- Communication and education is consistent

If you are on Twitter, follow @PCRSUK and join in the conversations on #nowastenoharm

REFERENCES

1. Primary Care Respiratory Society. Greener Respiratory Healthcare that is kinder to the environment; November 2020. https://www.pcrs-uk.org/resource/greener-healthcare

2. Legislation.gov.uk. 2018. Climate Change Act 2008. https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2008/27/contents

3. NHS Sustainable Development Unit. Carbon hotspots. https://www.sduhealth.org.uk/areas-of-focus/carbon-hotspots.aspx. Available from 1 March 2021 at: https://www.england.nhs.uk/greenerNHS

4. Kavanagh J, Jackson D, Kent B. Over- and under-diagnosis in asthma. Breathe. 2019;15(1):e20-e27.

5. Walters J, Walters E, Nelson M, et al. Factors associated with misdiagnosis of COPD in primary care. Primary Care Respiratory Journal. 2011;20(4):396-402.

6. Wilkinson A, Braggins R, Steinbach I, Smith J. Costs of switching to low global warming potential inhalers. An economic and carbon footprint analysis of NHS prescription data in England. BMJ Open. 2019;9(10):e028763.

7. Keeley D, Scullion J, Usmani O. Minimising the environmental impact of inhaled therapies: problems with policy on low carbon inhalers. European Respiratory Journal 2020;55(2):2000048.

8. Fraser, Sarah. Undressing the Elephant; Why Good Practice Doesn't Spread in Healthcare. United Kingdom: Lulu.com, 2008.

9. Primary Care Respiratory Society. Consider wider clinical issues before switching to green inhalers. Press release 1 November 2019. https://www.pcrs-uk.org/news/consider-wider-clinical-issues-switching-green-inhalers

10. Pinnock H. Supported self-management for asthma. Breathe. 2015;11(2):98-109

11. NICE. Patient decision aid. Inhalers for asthma; 2019 https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng80/resources/inhalers-for-asthma-patient-decision-aid-pdf-6727144573?UID=26790769820201010194112

Related articles

View all Articles