Getting spirometry right: an innovative approach to training

Claire Adams

Claire Adams

RGN

Director, Quality Clinical Solutions Ltd

The NHS Long Term Plan, published in January 2019, states that the NHS will do more to detect and diagnose respiratory problems earlier.1 It states that around a third of people with a first hospital admission for an exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) have not previously been diagnosed. It suggests that there is work to be done to reduce variation in standards of spirometry, both in terms of performing the test and its interpretation.

The emphasis on primary care clinicians making respiratory diagnoses requires staff in primary to be appropriately trained to provide the specialist knowledge needed to take a thorough history, carry out relevant tests and interpret results.

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is a common, preventable and treatable disease that is characterised by persistent respiratory symptoms and airflow limitation that is due to airway and/or alveolar abnormalities usually caused by significant exposure to noxious particles or gases.2

Asthma is a heterogeneous disease, usually characterised by airway inflammation. It is defined by the history of respiratory symptoms such as wheeze, shortness of breath, chest tightness and cough that vary over time and in intensity, together with variable and reversible expiratory airflow limitation.3

Both diseases can be challenging to diagnose and manage in primary care, and they can give rise to high, unplanned financial outlay by primary care organisations. According to RightCare, respiratory diseases account for the highest proportion (19.6%) of non-elective admissions across the nine highest spending areas.4

It is becoming apparent that measured outcomes for respiratory patients are unreliable, being largely focused on the Quality Outcomes Framework (QOF), a system which is not working to reduce this non-elective spend. Areas where practices achieve high QOF point scores can have significantly higher admission rates compared with other practices with the same QOF scores.5

In England, it is common in general practice for diagnostic and monitoring spirometry to be undertaken by general practice nurses (GPNs) and health care assistants (HCAs) who may have attended (unaccredited) workshops or study days on spirometry and then attempted to transfer their newly acquired knowledge into practice. A small number of nurses will have completed the recognised accreditation with the Association of Respiratory Technology and Physiology (ARTP). However, a UK-wide survey found that only 20% of primary care nurses who always used spirometry to diagnose COPD had undertaken any form of formal accredited training.6

Organisations such as Education for Health in Warwick and the Rotherham Respiratory centre have been providing accredited spirometry training in the UK for several years and continue to offer it. However, since January 2019, the ARTP assessment and access to the national register is only available via the Institute of Clinical Science and Technology (ICS&T) (www.clinicalscience.org.uk/national-artp-spirometry-programme/).

QUALITY STANDARDS

In 2013, a collaborative document was publishing involving the ARTP, Education for Health, the NHS, the British Thoracic Society (BTS) and the Primary Care Respiratory Society (PCRS) entitled ‘A Guide to Performing Quality Assured Diagnostic Spirometry’.7 This document highlighted that around 25% of patients on GP COPD registers do not meet the diagnostic criteria for COPD and therefore may be receiving inappropriate and expensive therapies. This level of misdiagnosis occurs because not only does much of the diagnostic spirometry currently performed fail to meet the essential quality standards, but also – even if the traces are quality-assured – the results may be misinterpreted.

In 2016, in response to this document, NHS England determined that the variation of quality in spirometry was not acceptable, and therefore proposed that by 2021, all practitioners who perform and/or interpret spirometry should hold the ARTP certification.8

Pre-January 2019, the usual format for ARTP training for performing and interpreting would be for the training provider to offer a 6-month online course to include two face-to-face study days for delegates. This would include access to online learning materials throughout the duration of the 6-month course (and for 6 months beyond), until submission of a portfolio of evidence, which would contribute to their assessment of competence and subsequent qualification. Crucially, however, there is currently no mechanism within any ARTP training course to provide one-to-one support to delegates in their own practice. Data from Education for Health for 2016-2017 demonstrated a pass rate of 74% for delegates on the ‘full certificate’ (performing and interpreting) programme.

As a result of feedback from nurses, an opportunity to provide one-to-one support to delegates was identified, to increase confidence in the individual clinician’s ability to perform and interpret spirometry to the standard required by the ARTP. It was thought that this approach would also lead to a higher overall pass rate.

The hypothesis was that this approach to spirometry training would help clinicians to develop greater confidence in the diagnosis (and, moving forward, the management) of conditions such as asthma and COPD. The potential improvements in each individual clinician’s confidence would also enable them to question and identify inaccurate diagnosis.

INNOVATIVE APPROACH

In Sunderland, the CCG’s local workforce development team was aware of a spirometry course that had been commissioned by the nearby Newcastle CCG in recent years, where a pass rate of only 10% was achieved on a 2-day ARTP course. As a result, Sunderland CCG was keen to invest in a new approach to spirometry training.

Quality Clinical Solutions (QCS) successfully pitched a proposal to deliver Education for Health’s 6-month ARTP-accredited spirometry course with the standard two days of face-to-face training. Following on from this, each delegate would be provided with three half-day visits in their own practice by a QCS nurse (accredited in spirometry) to be spread over the 6-month course, and before their portfolio submission date.

The in-house support was intended to ensure that each delegate had:

- An explicit understanding of requirements of the portfolio

- Support to ensure that the equipment that they were using was fit for purpose and in good working order and how to check this

- Opportunities to review the evidence gathered for their portfolio with the visiting clinician

- Opportunities to discuss case studies and consider how a quality assured spirometry test could impact on those discussions

- Opportunities to review asthma and COPD management strategies in practice in the context of local guidelines

- An understanding of national and local guidelines for asthma and COPD, and knowledge and competencies regarding inhalers and inhaler technique;

- Bespoke respiratory support.

The project sought to address the issue of the gap between competence and confidence as well as to improve pass rates. It was felt the traditional approach to spirometry training could be aligned to the processes within the ‘Four stages of competence’,9 in that spirometry is a practical skill and then requires its interpretation to be applied to the clinical context of the presenting patient, in order to achieve accurate and successful outcomes. As a result of training the ARTP Spirometry programme over several years, the author has observed that many of the delegates on a traditional spirometry course would be ‘unconsciously incompetent’, but after the first study day, achieved an awareness of ‘conscious incompetence’. The aspiration was that during the course, the delegate would progress to ‘conscious competence’. However, it can be construed through the pass rates observed that too many delegates did not reach this stage.

In March 2017, 19 delegates were enrolled onto the new programme, of whom 17 completed the course.

On completion, 100% of the delegates achieved a pass on their first attempt and were therefore entered onto the ARTP register with a ‘full certificate’.

Education for Health spirometry clinical lead, Chris Loveridge, commented that this was the first time a 100% pass rate has been achieved in her 11 years with the organisation.

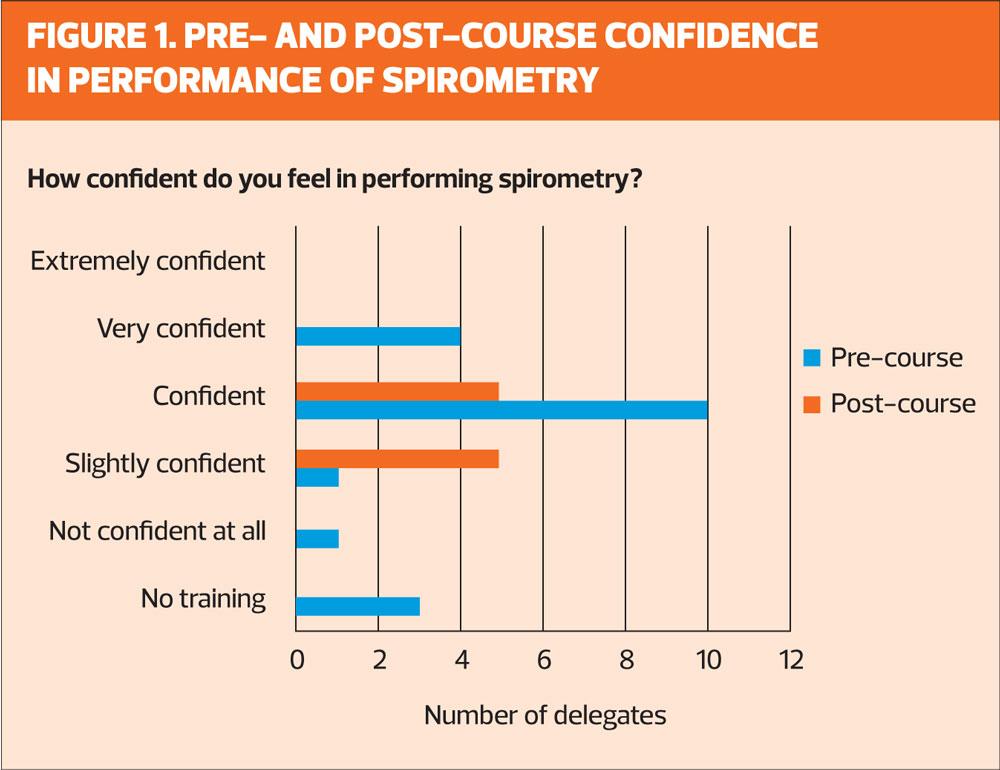

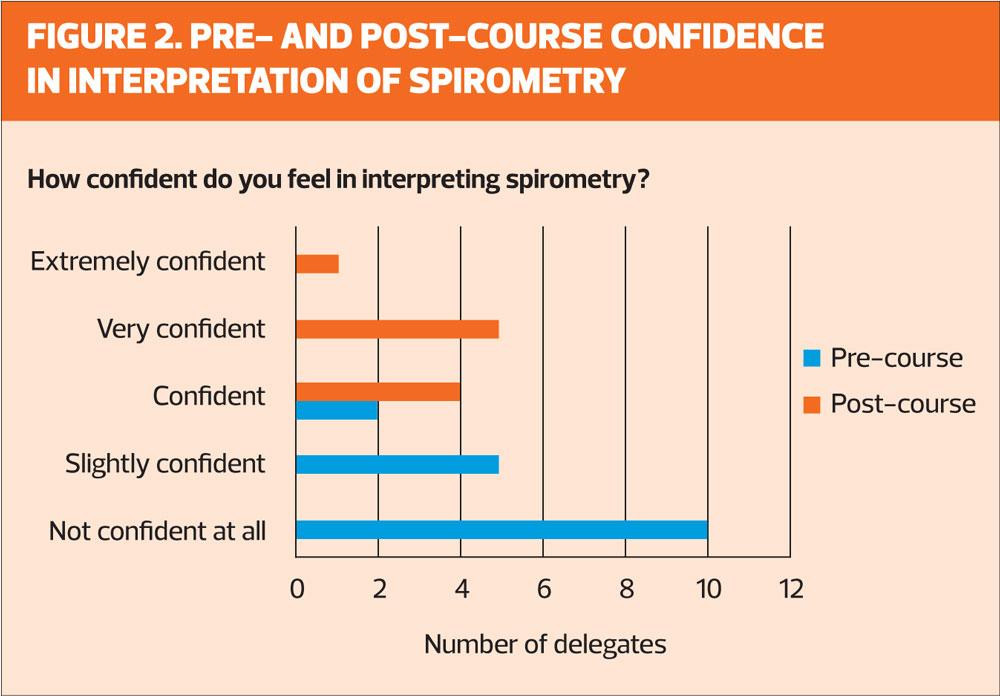

A further aim of the project was not only to improve pass rates, but also increase nurses’ confidence. Delegates were asked to complete a confidence questionnaire on the first study day, and again at the end of the course. (Figures 1 and 2).

Most delegates (84%) had had some form of (non-accredited) spirometry training prior to the course, and most of the delegates felt that they had confidence in both performing and interpreting the test; however, during the programme, some commented that although they had perceived that they were performing the test well, now that they had had the formal training and had a better understanding of the accuracy of the test, they had moved from being ‘unconsciously incompetent’ to ‘consciously incompetent’. As the training moved on, delegates advanced into ‘conscious competence’ as a result of the extra support that was being offered.

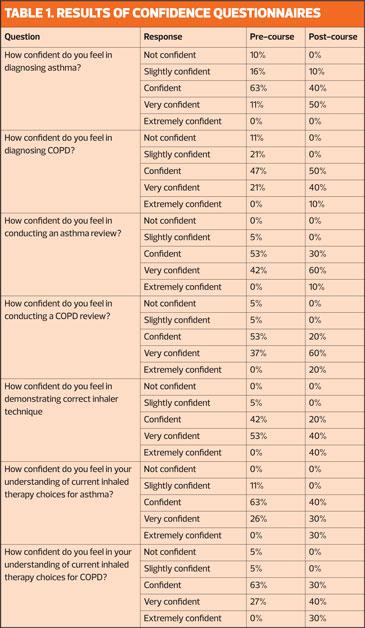

The project sought to improve spirometry outcomes, but also provide increased confidence in the diagnosis and management of asthma and COPD. Table 1 shows the results of the questionnaires administered at the start and end of the programme (before spirometry accreditation results were received).

RESULTS

The results demonstrate that overall, there was an improvement in confidence levels as a result of the support that the programme offered and which went far beyond improving spirometry technique and interpretation. Local guidelines for asthma and COPD management were reviewed with each delegate and used as an opportunity for case management discussion. Delegates reported that the time provided with each of them in their own practice to allow for this discussion and reflection was invaluable.

A further cohort was commissioned by Sunderland in 2018 and the results were also comparable in that 87% of delegates were awarded a pass on their first attempt. The remaining 13% of the delegates who were not successful, tried again and were successful on their second attempt, and therefore the pass rate overall was also 100%. Results of the confidence questionnaire were similar to the previous year. Sunderland CCG has commissioned a third cohort based on the success of the first two projects and this commenced in June 2019.

SUMMARY

Spirometry remains crucial in assisting in the diagnosis of respiratory disease. The recommendations in the NHS Long Term Plan set out the importance of training and up-skilling the workforce, but just as crucially, the workforce needs to have understanding and confidence in how to apply spirometry to the clinical picture in order to ensure correct diagnosis, correct management and to review an existing diagnosis to ensure its accuracy.

The project has shown that with extra support, all members of the cohort achieved a pass result on their first attempt. The added-value element of this project demonstrated an increase in confidence both in the diagnosis and management of asthma and COPD. If competence and confidence levels are increased then this will have a positive impact on helping the delegate to successfully achieve conscious competence, but also have a positive effect on outcomes such as prescribing costs and non-elective admissions and, more importantly, ensure provision of a gold standard service for patients.

It is also worth pointing out that staff who feel valued and who are supported in their role are likely to remain in post – an important consideration when nursing recruitment and retention is a challenge for general practice and beyond.

- Acknowledgement: With thanks to Chris Loveridge for her support during this project and subsequently

REFERENCES

1. NHS England. NHS Long Term Plan, 2019 https://www.england.nhs.uk/long-term-plan/

2. Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD). Global Strategy for the Diagnosis, Management and Prevention of Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease, 2019 report. https://goldcopd.org/

3. Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA). Global Strategy for Asthma Management and Prevention, updated 2019. https://ginasthma.org/

4. NHS England. RightCare Intelligence products, 2019 https://www.england.nhs.uk/rightcare/products/

5. Purdy S. Kings Fund: Avoiding hospital admissions. What does the research evidence say? 2010 https://www.kingsfund.org.uk/sites/default/files/Avoiding-Hospital-Admissions-Sarah-Purdy-December2010.pdf

6. Upton J, Maddoc-Sutton H, Sheikh A, et al. National Survey on the roles of training of primary care respiratory nurses in the UK in 2006: are we making progress? Primary Care Respiratory Journal 2007;16(5):284-90

7. Primary Care Commissioning. Quality Assured Diagnostic Spirometry, 2013. https://www.pcc-cic.org.uk/sites/default/files/articles/attachments/spirometry_e-guide_1-5-13_0.pdf

8. Primary Care Commissioning. Improving the quality of diagnostic spirometry in adults, 2016 https://www.pcc-cic.org.uk/sites/default/files/articles/attachments/improving_the_quality_of_diagnostic_spirometry_in_adults_the_national_register_of_certified_professionals_and_operators.pdf

9. Burch N. Learning a new skill is easier said than done.1970 https://www.gordontraining.com/free-workplace-articles/learning-a-new-skill-is-easier-said-than-done/

Related articles

View all Articles