Cough: something simple or more sinister?

Hazel Hart

Hazel Hart

RGN BSc

Primary Care Advanced Nurse Practitioner. Wyre Forest Health Partnership, Bewdley, Worcestershire

Practice Nurse 2022;52(7):25-30

Cough is one of the most common presentations in primary care. Most coughs are innocuous and acute in nature, but they can also be one of the first signs of a life-threatening illness

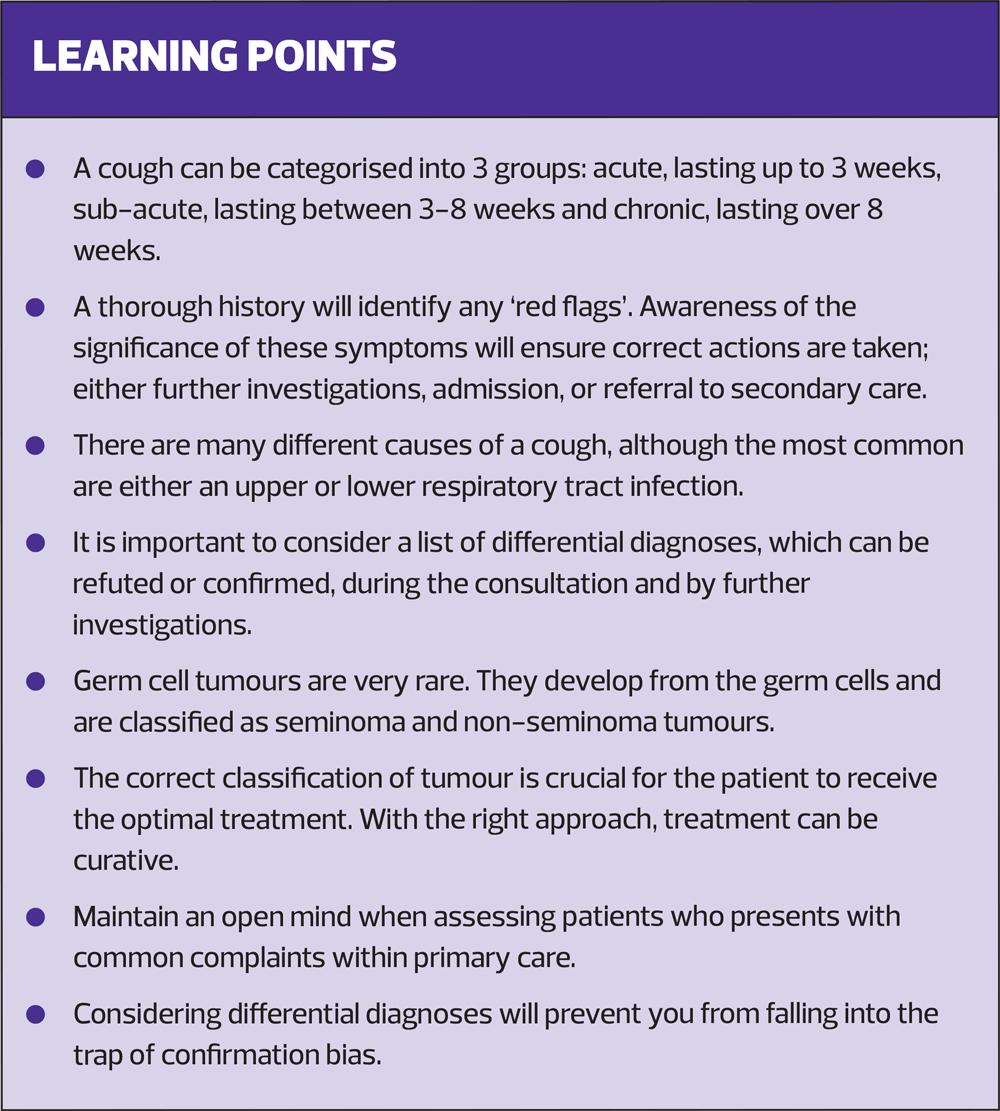

When is a cough NOT just a cough? This is a question clinicians should be asking themselves. Cough is a very common reason for patients to visit primary care. The majority of coughs are associated with viral upper respiratory tract infections, and, in the absence of significant co-morbidity, are normally benign and self-limiting.1,2 However, a cough can be the first indication of a serious condition. This article, based on a case study of a patient that I saw in general practice a few months ago, demonstrates this point. It shows the need to keep an open mind, consider differential diagnoses, and not fall into the trap of confirmation bias, discussed in more detail later. The diagnosis of this patient surprised both myself and my fellow clinicians.

JACK: A CASE STUDY

Jack is a 32-year-old. He contacted the surgery with a history of cough, on and off for 6-8 weeks, and haemoptysis for a few days. I spoke to him on the telephone to gain a history. Due to the haemoptysis it was decided that he needed a face to face appointment and I saw him myself later that morning.

During the consultation I took a thorough history. I established that he had had the cough for a total of 7 weeks, initially for 3 weeks, then it settled for a week and then recurred for the past 3 weeks. Over the last week Jack had experienced haemoptysis – small amounts of blood mixed in his sputum after coughing in the mornings. There was no history of weight loss, or any other red flags or systemic symptoms and I therefore considered a diagnosis of a lower respiratory tract infection.

Jack has never smoked and only drinks alcohol socially. His past medical history is insignificant, except for hay fever. He was not taking any medication and there was also nothing of note in his family history. Both his parents are alive and well, although his grandmother, a heavy smoker, died of lung cancer.

I then proceeded to examine him. His chest was clear. There were no crackles, wheezes or focal sounds and there was good, equal, bilateral air entry. Jack was apyrexial and his pulse, respiratory rate and oxygen saturation were all in the normal range. Examination of his ears, nose and throat was also normal. Consequently, the lack of any significant examination findings refuted my original provisional diagnosis and, due to his normal examination, ongoing cough and haemoptysis, a chest X-ray (CXR) was requested. The CXR showed soft tissue masses in the right lung. Jack was sent for a computerised tomography (CT) scan of his chest, pelvis and abdomen, and a respiratory referral, under the 2 week wait, was initiated. The CT scan confirmed a peripheral right lung mass with hilar and mediastinal lymphadenopathy.

He was seen by the lung cancer team and an endobronchial ultrasound and biopsy was performed. The resulting histology showed a mass consistent with a germ cell tumour with a component of embryonal carcinoma. Because this was uncommon and required accurate classification for optimal treatment, the histology was sent for an expert review. The diagnosis was confirmed and it was concluded that the lung nodule was probably a metastasis. Exclusion of a testicular source for the primary malignancy was recommended and Jack was referred for a multi-disciplinary team (MDT) review and for specific germ cell tumour markers. This is discussed in more detail later.

Jack proceeded to have magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain and an ultrasound scan (USS) of the testes. The MRI was clear but the USS showed a solid, heterogeneous lesion in left testis. A diagnosis of metastatic germ cell tumour of testicular primary origin was made, and Jack’s care was transferred to a specialist oncology unit.

COUGH

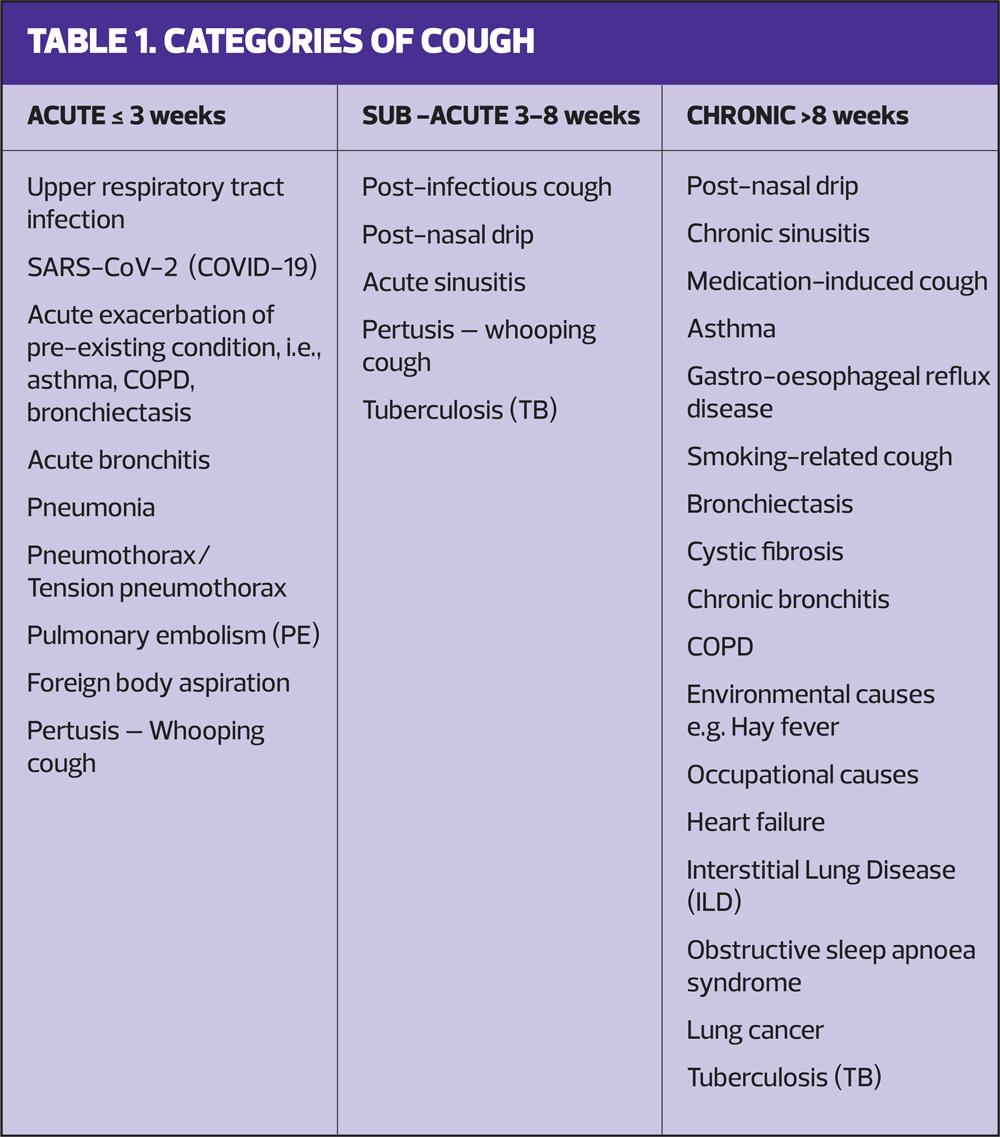

Cough is a frequent symptom of many different conditions and is classified into three categories:3

- Acute – usually lasts less than 3 weeks

- Sub-acute – lasts for 3-8 weeks

- Chronic - persisting beyond 8 weeks.

The causes of these three categories are summarised in Table 1.

Categories of cough

All coughs start as an acute cough. Often the causes of acute and sub-acute cough overlap. Patients may not present to primary care until they have had symptoms for a few weeks, or the underlying cause may not manifest immediately.

Common causes for an acute cough are:

- Upper and lower respiratory tract infections

- COVID-19

- Acute exacerbations of pre-existing conditions, such as asthma, COPD, bronchitis.

- Pneumonia

- Post-infectious cough

- Postnasal drip.

Rarer, but more serious causes of an acute cough, such as pneumothorax, pulmonary embolism (PE), foreign body aspiration and tuberculosis (TB), will need either immediate or routine exploration.2,3

Patients with chronic cough often have it for months before presenting to primary care, and present because it is becoming troublesome or not settling.3 The causes of chronic cough can range from the innocent, but annoying, e.g. postnasal drip, chronic sinusitis, drug induced cough, to treatable, long-term conditions e.g. asthma, COPD, gastro-oesophageal reflux disease (GORD), obstructive sleep apnoea. It can also be one of the first signs of a serious underlying pathology, e.g. lung cancer, tuberculosis, pulmonary fibrosis, pulmonary hypertension. It can also have a cardiac cause, e.g. congestive cardiac failure, valvular disease.

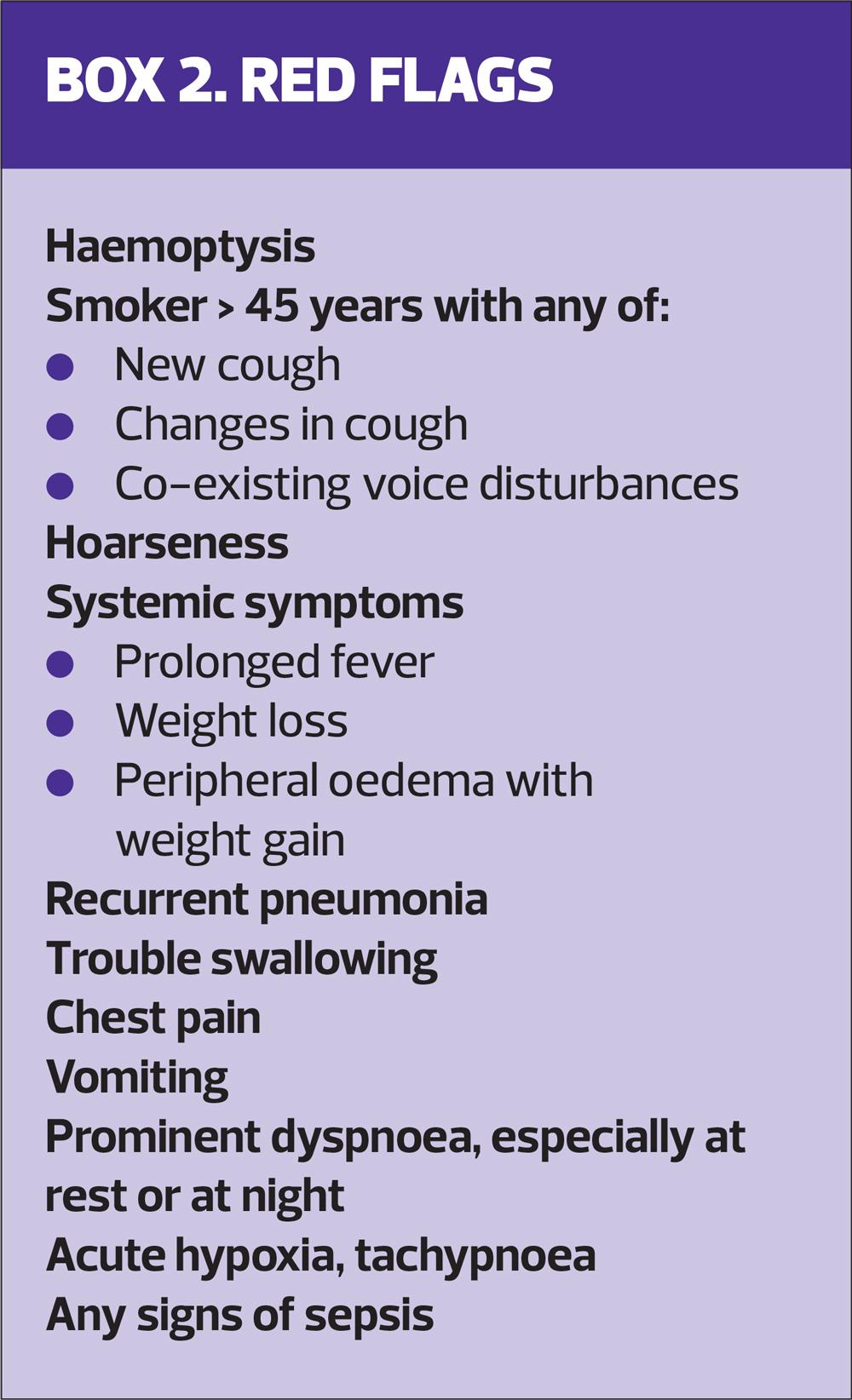

For most patients with underlying causes, cough is not the only symptom they present with. Taking a thorough history will help identify concerning associated symptoms, prompting the initiation of investigations, e.g. blood tests, CXR, pulmonary function tests, or, if required, referral/admission to secondary care. Red flags include:

- Haemoptysis

- Hoarseness

- Weight loss

- Peripheral oedema with weight gain

- Swallowing difficulty

- Prominent dyspnoea, especially at rest or at night

- Any signs of sepsis.

Red flag symptoms should always prompt further questioning,1-3 and are summarised in Box 2.

The abnormal CXR result meant that Jack was immediately referred for urgent CT scan and to the respiratory team under the 2-week wait. Delays in investigation and referral can make significant differences in the final outcome.4,5

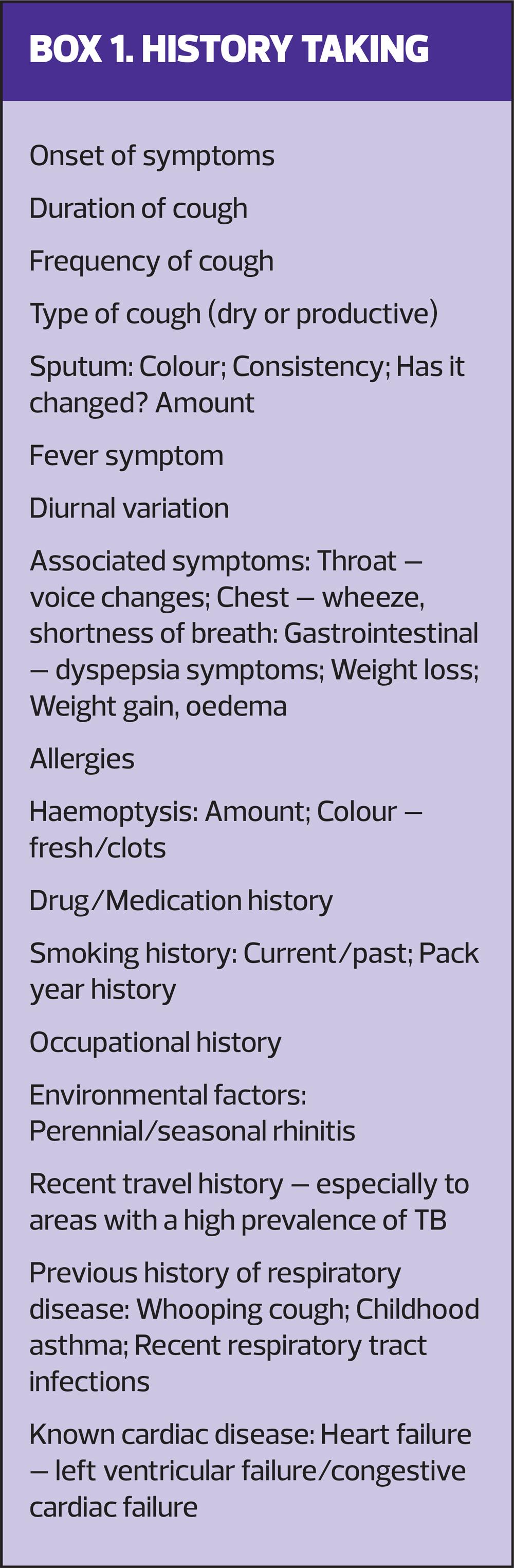

Taking a history of cough

Because cough can either be due to minor but troublesome causes, which are self-limiting or harmless, or an indication of a serious underlying condition, it is essential that a comprehensive history, using open questioning, is taken at initial presentation. Enquire about the cough itself, asking about:

- Onset

- Duration, and frequency

- Whether the cough is dry or productive – if productive, explore sputum presentation.

Ask if there are any associated symptoms, such as:

- Fever

- Haemoptysis

- Gastrointestinal symptoms

- Weight loss

- Any peripheral oedema.

You will also need to delve into the individual’s current and past medical history, highlighting any ongoing history of cardiac and respiratory diseases. Ask about any medications that the patient is taking; over the counter, recreational, and prescribed such as angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitor or sitagliptin. Enquire further about the family history, occupational history and environmental factors, including smoking history and any recent travel, especially to areas with a high prevalence of tuberculosis.3,5

History taking that is specific for a presentation of cough is summarised in Box 1.

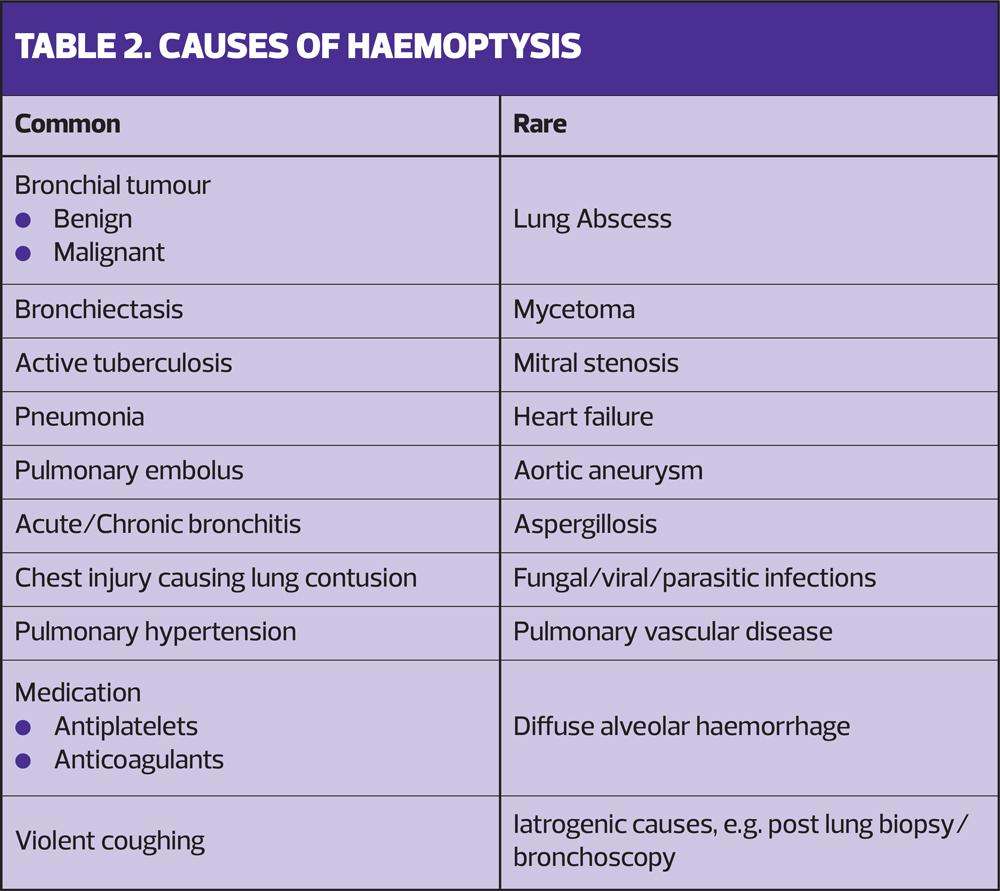

HAEMOPTYSIS

Haemoptysis is a common and non-specific symptom, but it can be a sign of significant underlying lung disease, such as:

- Bronchial tumours

- Bronchiectasis

- Pulmonary embolism

- Active tuberculosis

- Pulmonary hypertension

- Fungal, viral or parasitic infection.

It can also be due to cardiac problems such as mitral stenosis or congestive cardiac failure. However, in up to one-third of cases no cause is found.5

The degree of haemoptysis can vary from mild streaks of blood to massive haemorrhage, which needs emergency assessment. In Jack’s case, it was mild, streaks of blood in the sputum, only in the morning, so was not life threatening and could be safely investigated in primary care. For a full list of common and rare causes of haemoptysis see Table 2.

Haemoptysis is present in up to 20% of patients with a bronchogenic carcinoma and is likely to result in this 20% presenting early in the disease course.6 Most lung cancers are diagnosed following symptomatic presentation within primary care,5 but unfortunately at least 80% of cases do not present with haemoptysis and are diagnosed at a later stage, when the prognosis is poor. Like bronchogenic carcinoma, pulmonary metastases from a testicular primary are most commonly asymptomatic and are often only found on imaging. They will rarely present with cough and haemoptysis.7 Jack’s presentation was unusual.

KEEPING AN OPEN MIND

History taking and examination of the patient are essential to making an accurate diagnosis. A thorough history can guide the practitioner to a provisional diagnosis, whereas examination and investigations merely confirm or refute that proposed diagnosis.8 Even though the practitioner will have contemplated a diagnosis, they will also be consciously or subconsciously formulating a list of differential diagnoses, depending on their knowledge and experience.9

The more experienced a practitioner is, the more intuitive decision making is used, often triggered by situation recognition.10 The formulation of differential diagnoses will therefore often occur subconsciously. The clinician will be more willing to change direction when unfolding events show their initial approach was wrong, being less likely to fall into the trap of confirmation bias.

CONFIRMATION BIAS

Confirmation bias is the tendency to interpret evidence in a way that ‘confirms’ or supports a preliminary diagnosis, disregarding or failing to seek evidence that contradicts this diagnosis.11,12 This can lead to misdiagnosis, delayed diagnosis, or diagnostic errors, which may cause significant harm to the patient. Potential confirmation bias errors by can be avoided by using the following strategies:

- Maintaining an open mind: being open to the idea that the provisional diagnosis may be wrong if findings do not fit.

- Using reflecting thinking. After deciding on a considered diagnosis asking, ‘could this be something else?’, and formulating a list of differential diagnoses.

- Enquire. Does the contemplated diagnosis fully fit the patient’s presentation? If there is any doubt, discuss the case with a colleague. An alternative opinion can be helpful and give a new perspective.11

Misdiagnosis, and diagnostic delay, have the potential to incur serious harm to the patient and can result in a multitude of inappropriate treatment options.11 In this case, had I treated Jack for a lower respiratory tract infection, which was the provisional diagnosis, and not ordered a CXR, this would have delayed the diagnosis of an aggressive metastatic tumour, causing a delay in his treatment with the chance of worsening his prognosis.

GERM CELL TUMOURS

Germ cells are the cells that develop into sperm and eggs. Germ cell tumours therefore most commonly develop within the ovaries or testicles. Testicular germ cell tumours are rare. They account for about 1% of all male neoplasms with an incidence of 3-10/100,000 males per year in the western world.13,14 Yet germ cell tumours are the most common type of cancer in men aged 20–40 years.14 Fortunately they are highly treatable and usually curable.15

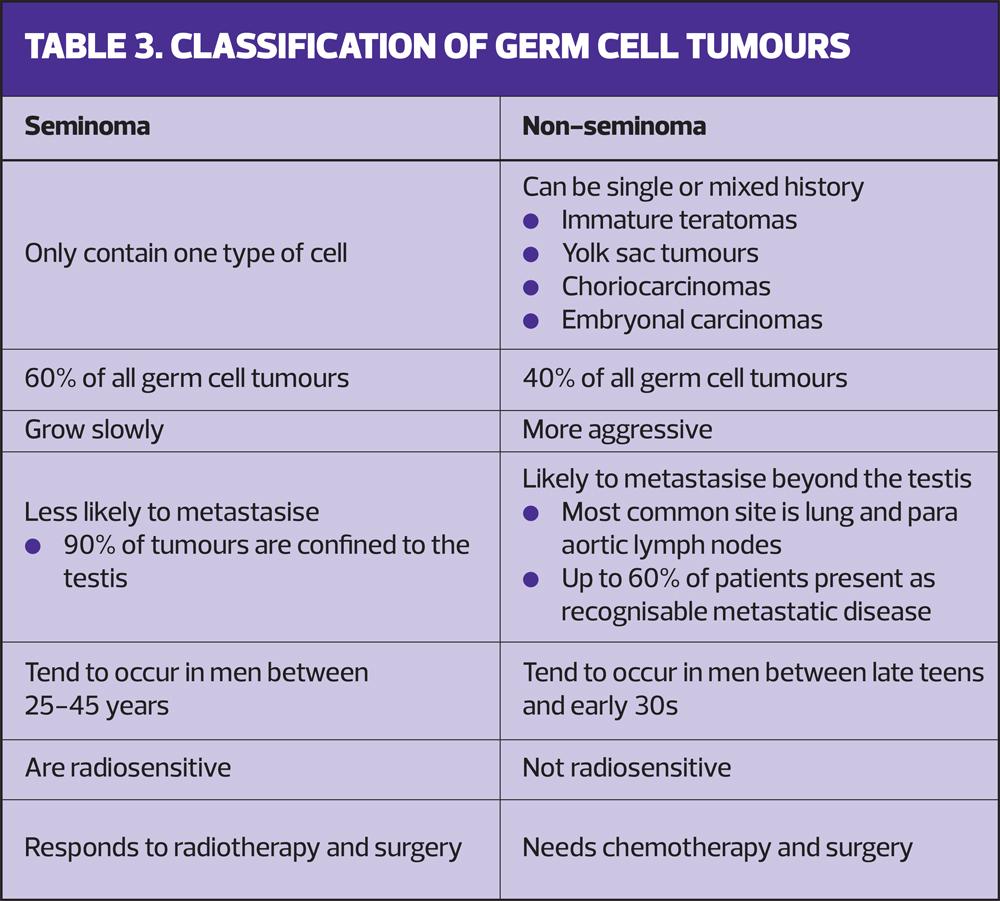

Most testicular cancers are germ cell tumours and they can be categorised into seminomas and non-seminomas (Table 3). Seminoma tumours are 100% seminoma. All other tumours, including those with a mixture of seminoma and non-seminoma components, are classified and should be managed as non-seminoma tumours. The correct classification is essential as the prognostic and treatment approaches are different.15 Jack’s tumour was classified as metastatic embryonal mixed tumour with a testicular primary. The lungs and surrounding lymph nodes are the most common sites for this type of metastasis.16,17

Survival rates for patients with germ cell tumours are high. Prognosis depends on:

- The tumour histology

- The level of elevation of tumour markers

- The extent of metastases

- The age of the patient

- The quality of care – patients treated in specialist centres do better.14

Tumour markers are fundamental for the diagnosis, treatment, prognosis, and monitoring.

- Alfafetoprotein (AFP) – not raised in seminoma tumours but elevated in 60% of non-seminoma tumours

- Beta-Human Chorionic Gondatrophin (B-HCG) – raised In 15% of seminoma tumours and in 60% of non-seminoma tumours

- Lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) – raised in both seminoma and non-seminoma tumours and elevation may be the first sign of relapse following treatment.

Tumour markers therefore enable differentiation between seminoma and non-seminoma tumours. This is important as seminoma tumours are radiosensitive and responsive to treatment with radiotherapy. Non-seminoma tumours are not.18 Tumour markers need to be measured as part of the initial investigation, prior to surgery and after surgery as the degree of elevation after surgery is an important predictor of prognosis.

Jack’s B-HCG levels were high, and the AFP and LDH were also raised, putting him in a high risk group and enabling classification of his tumour as a non-seminoma. Jack’s plan is therefore to have combined chemotherapy and surgery, not radiotherapy.

At the time of writing Jack had been referred to a specialist oncology unit and has started his treatment of four cycles of 5 days bleomycin, etoposide, and cisplatin (BEP) chemotherapy. Once all four cycles are complete, he will have an orchidectomy. Prior to commencing his chemotherapy, Jack received counselling and has banked his sperm. His treatment is given with a curative intent, with a 5-year survival rate of over 80%.

SUMMARY

Coughs are one of the most frequent presentations within primary care, and can be a symptom of many different conditions, most commonly upper respiratory tract infection. However, it can be the first sign of significant underlying disease. Therefore, it is essential to take a comprehensive history at the initial presentation, taking note of any associated symptoms or red flags and acting on them.

Many nurses working in primary care have taken on autonomous roles. Above all, it is vital to work within your competence.19 Keeping an open mind, acknowledging differential diagnoses, discussing cases with colleagues and mentors, and ensuring appropriate investigations are conducted and results acted on is vital.

This article used a practice case study and, while it highlights many salient issues, I acknowledge that the list is not exhaustive. It is intended to provide an overview of cough, red flags and associated symptoms, and gives an introduction to germ cell tumours. Furthermore, it emphasises the importance of keeping an open mind and considering differential diagnoses when consulting with patients who present with common complaints in primary care.

REFERENCES

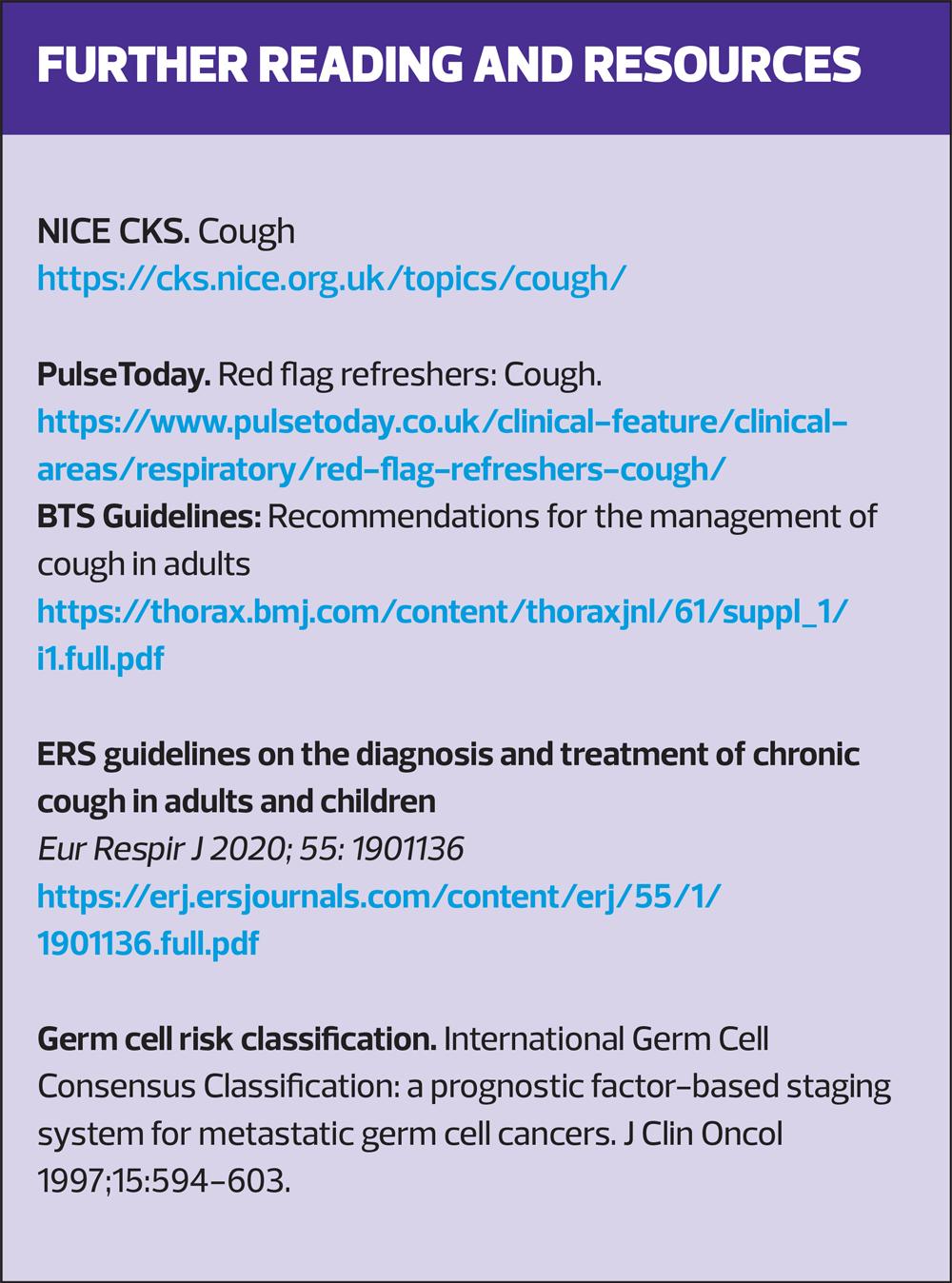

1. Morice A, McGarvey L, Pavord I, on behalf of the British Thoracic Society Cough Guideline Group. BTS GUIDELINES Recommendations for the management of cough in adults. 2006 https://thorax.bmj.com/content/thoraxjnl/61/suppl_1/i1.full.pdf

2. Turner R. Red flag refreshers – cough. PulseToday 2019 https://www.pulsetoday.co.uk/clinical-feature/clinical-areas/respiratory/red-flag-refreshers-cough/

3. NICE Clinical Knowledge Summaries. Cough; 2021 https://cks.nice.org.uk/topics/cough/

4. Neal RD, Hurt C, Roberts K, et al . A feasibility randomised controlled trial looking at the effect on lung cancer diagnosis of giving a chest X-ray to smokers aged over 60 with new chest symptoms: the ELCID trial. Lung Cancer 2014; 83: S81"S82 https://doi.org/10.1016/S0169-5002(14)70220-X

5. Chapman S, Robinson G , Shrimanker R, et al. Oxford Handbook of Respiratory Medicine (4th Edition). Oxford University Press. 2021 https://oxfordmedicine.com/view/10.1093/med/9780198837114.001.0001/med-9780198837114-part-1

6. Webb A, Angus D, Finfer S, et al. Oxford Textbook of Critical Care (2nd Edition) 2016 Chapter 4. Blasi F, Tarsia P. Pathophysiology and causes of haemoptysis. https://oxfordmedicine.com/view/10.1093/med/9780199600830.001.0001/med-9780199600830-chapter-126

7. Duangkham S, Wichmann A, Sekhon J, et al. Hemoptysis and bleomycin injury in testicular cancer: When pulmonary metastases turn bloody. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2021;203:A4930 available from https://www.atsjournals.org/doi/pdf/10.1164/ajrccm-conference.2021.203.1_MeetingAbstracts.A4930

8. Thomas J, Monaghan T. Oxford Handbook of Clinical Examination and Practical Skills (2nd Edition.) 2014. Oxford University Press

9. Llewelyn H, Hock Aun Ang , Lewis K, et al. Oxford Handbook of Clinical Diagnosis (3rd Edition) 2014. Oxford University Press

10. Davey P, Sprigings D. Diagnosis and Treatment in Internal Medicine. 2018. Oxford University Press.

11. Vasdev N, Moon A,C, Thorpe A. Classification, epidemiology and therapies for testicular germ cell tumours. Int. J. Dev. Biol. 2013; 57: 133 – 139. http://www.ijdb.ehu.es/web/paper.php?doi=10.1387/ijdb.130031nv.

12. Kliesch S, Schmidt S, Wilborn D, et al. Management of germ cell tumours of the testis in adult patients. German Clinical Practice Guideline Part I: Epidemiology, Classification, Diagnosis, Prognosis, Fertility Preservation, and Treatment Recommendations for Localized Stages. Urologia Internationalis 2021;105(3-4):169-180 https://www.karger.com/Article/FullText/510407

13. National Institute of Health National Library of Medicine. Testicular Cancer Treatment (PDQ®) PDQ Cancer Information Summaries. 2002 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK65777/

14. Smith T. Four widespread cognitive biases and how doctors can overcome them. AMA Journal of Ethics. 2021 https://www.ama-assn.org/delivering-care/ethics/4-widespread-cognitive-biases-and-how-doctors-can-overcome-them

15. Elston MD. Confirmation bias in medical decision-making. JAAD 2020; 82(3): P572. https://www.jaad.org/article/S0190-9622(19)32285-6/fulltext

16. Cancer Research UK. What are germ cell tumours? 2022. https://www.cancerresearchuk.org/about-cancer/germ-cell-tumours

17. Hamdy F, Eardley I. Oxford Textbook of Urological Surgery. 2017. Oxford University Press. https://oxfordmedicine.com/view/10.1093/med/978019965959579.001.0001/med-978199659579-chapter-91?rskey=sqxzb6&result=5

18. Townsend CM, Beauchamp RD, Evers BM, Mattox KL. Sabiston Textbook of surgery: the biological basis of modern surgical practice; Chapter: Lung, Chest Wall, Pleura and Mediastinum :Germ Cell Cancer. (2022) Elsevier: ISBN 9780323640664. quoted in https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/medicine-and-dentistry/germ-cell-cancer

19. Nursing and Midwifery Council. The Code: Professional Standards of Practice and Behaviour for Nurses and Midwives; 2015. https://www.nmc.org.uk/standards/code/

Related articles

View all Articles