Asthma-COPD overlap: diagnosis and management

Beverley Bostock-Cox

Beverley Bostock-Cox

RGN, MSc, MA, QN

Nurse Practitioner Mann Cottage Surgery Moreton in Marsh

Education Lead, Education for Health Warwick

Many general practice nurses will encounter people who appear to have a diagnosis of COPD but with some aspects of asthma in their history, or vice versa. This guide aims to help you identify these patients and to optimise their management

Although asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) have different underlying pathology, the symptoms and indeed the conditions themselves, can overlap. There are various reasons for this. First, smoking can make asthma harder to treat as the inhaled corticosteroids that are the mainstay of asthma treatment do not work as well in the presence of cigarette smoke.1 Secondly, chronic asthma, especially if it has been undertreated, can result in previously reversible changes becoming irreversible and fixed.2 Thirdly, asthma is itself a risk factor for fixed airways disease in the future.3

Asthma-COPD overlap is said to be present when elements of both conditions co-exist in the same individual. For example, it may be that a patient has variability of airflow limitation as seen in asthma but without the reversibility that is central to this diagnosis. Irreversible (or largely irreversible) airflow obstruction, often due to airway remodelling, would usually suggest a diagnosis of COPD but airway remodelling has also been seen in people with asthma. Inflammatory markers such as neutrophils and eosinophils have traditionally been considered to be associated with one or other condition – asthma (eosinophils) or COPD (neutrophils) – but recent studies suggest the role of these markers is not as clearcut as previously thought.4 In clinical practice, many of us will have seen people who appear to have a diagnosis of COPD but with some aspects of asthma in their history, or vice versa. Recognising who these people are and how best to manage them will ensure that their treatment and outcomes are optimised.

ACO OR ACOS – WHAT’S IN A NAME?

Previously, the asthma-COPD overlap was referred to as ‘asthma-COPD overlap syndrome’ or ACOS. However, in 2017, the Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA) group decided that the word ‘syndrome’ should be dropped because the term was being commonly used in the respiratory community as if it was a single disease – the asthma-COPD overlap syndrome – and because ACOS didn’t fit the medically-accepted definitions of syndrome.5

DIAGNOSING ASTHMA-COPD OVERLAP

A key difference between asthma and COPD is the issue of reversibility. Spirometry in COPD remains obstructed (FEV1/FVC <70%) following bronchodilation,6 whereas asthma is a reversible airways disease which, when treated appropriately, should result in normal or near normal lung function.7 The reversal of airflow obstruction, which is the aim of asthma treatment, should mean that symptoms (cough, wheeze, tight chest, shortness of breath) also resolve. In contrast, COPD symptoms (cough, breathlessness, sputum production and disability) often persist in spite of treatment. The diagnosis of asthma, COPD or ACO, then, will be made on the basis of all or some of the following: symptoms, risk factors, objective testing and response to a trial of treatment.

HISTORY, RISK FACTORS AND OBJECTIVE LUNG FUNCTION TESTS

Case study – Tracey

Tracey is 44 years old and is a smoker with a 40 pack year history. She runs her own business from home and is trying to quit smoking, without much success. She says smoking helps her to cope with the stress of the business. She presents with a cough and sputum and has noticed that she is more breathless when walking to her local village shop. She puts this down to getting older and the fact that she smokes.

Tracey’s history certainly suggests that she could have COPD as she has the most significant risk factor (smoking) along with typical symptoms of COPD. In a case such as this, where it would seem likely that the patient has COPD, the diagnosis should be confirmed by carrying out post bronchodilator spirometry. The expected findings would be a reduced FEV1/FVC ratio post bronchodilator of less than 70% (or 0.7) indicating obstruction. The combination of risk factors, symptoms and persistent airflow obstruction would confirm the diagnosis of COPD.6

However, Tracey’s history reveals some other interesting information, which makes her story less straightforward than it might at first appear to be. She has always suffered from intermittent ‘chest problems’ since childhood and she has two children, both of whom have asthma. She also has hay fever and in the summer she uses a daily anti-histamine with a nasal spray for her rhinitis and itchy eyes. She explains that over the past two or three summers her chest regularly felt tight and she was waking at night because of wheezing. She admits that when this happened she used her son’s blue reliever inhaler and that this helped. She says that at a previous GP practice, someone said she might have asthma and that she was advised to return for ‘some sort of lung check’. However, pressure of work meant that she never got around to it.[/italics]

From this history, then, we have a presentation which has a strong asthma element to it and indeed, using the British Thoracic Society/Scottish Intercollegiate Networks Guidelines (BTS/SIGN) guidelines Tracey has a high probability of asthma.7 In cases of high probability, the BTS/SIGN guidelines advise starting the patient on an inhaled corticosteroid (ICS) and reviewing them in six weeks to assess the impact of treatment. At this point they would be Read-coded as ‘suspected asthma’. If the diagnosis and treatment are correct, the patient should find that their lung function reverses back to normal or near normal with the ICS and that their symptoms have resolved. At this point the patient would be diagnosed and Read-coded as ‘asthma’.

However, Tracey is not as straightforward as this. Her history has elements of both asthma and COPD. In any case where the diagnosis is unclear, full spirometry and reversibility testing should be carried out.

Tracey had her lung function measured and her FEV1/FVC ratio was 59%. Her FEV1 was 66% predicted. She was given four puffs of salbutamol 100mcg via a pMDI and spacer and after 20 minutes her lung function improved so that her FEV1/FVC ratio was 64%. Furthermore, her FEV1 increased to 74% predicted and had improved by 12% and 210ml. For an asthma diagnosis, reversibility testing should result in a change of 12% or more plus 200ml or more, although 400ml or more is strongly positive.7

In essence, then, Tracey’s test shows evidence of reversibility but without the lung function returning to normal. Furthermore, her post bronchodilator test is in line with what would be expected for someone with COPD. Her symptoms are suggestive of both conditions and she also has risk factors for both. Tracey might therefore fit the description of someone with asthma-COPD overlap.

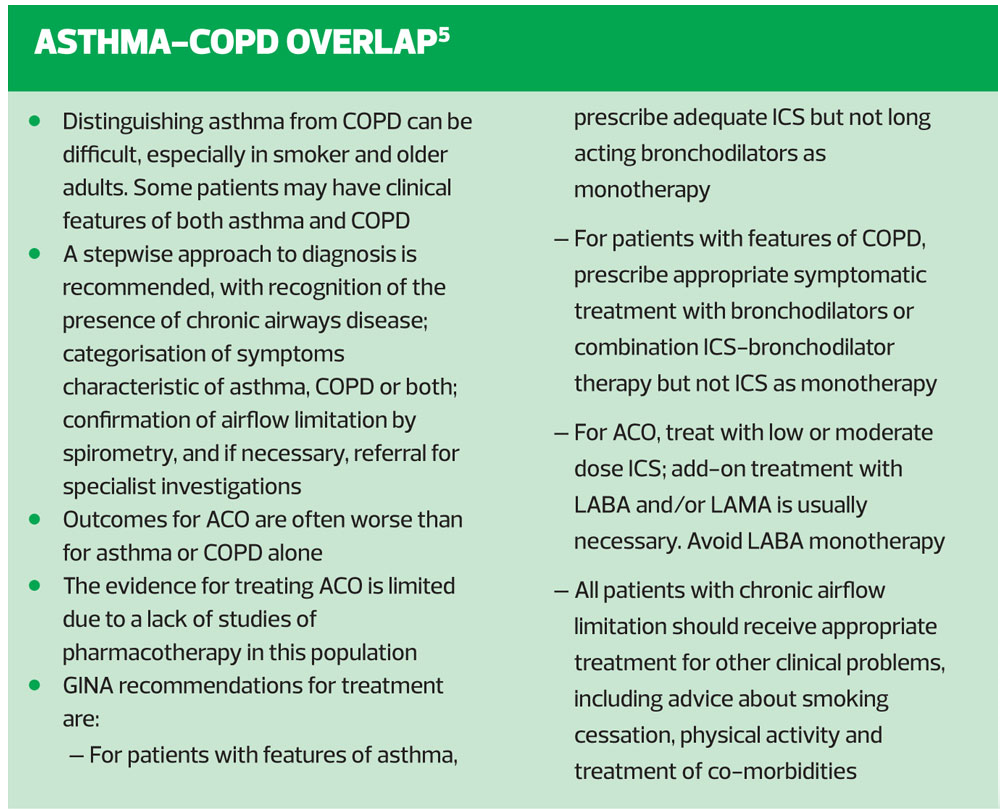

DRUG THERAPIES

The issue with managing people with asthma-COPD overlap is that there are no guidelines on this subject, unlike asthma and COPD, where there are guidelines on a local, national and even international level.6,7 There is also no inhaler that is licensed to treat ACO. Different inhaled therapies may have a licence for asthma or for COPD or even for both, but none have a licence to treat ACO, an arguably separate condition, which overlaps both diseases. This means, in effect, that clinicians have to decide the best way to treat each individual, based on their history and symptoms.

In Tracey’s case, the clinician might ask the question as to whether it would be better to follow the asthma guidelines predominantly or better to follow the COPD guidelines. It is important to consider this carefully as each guideline offers a very different approach to management. In asthma, for example, inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) are the mainstay of treatment and the long-acting bronchodilators should never be used without an ICS. Conversely, in COPD the focus is on using bronchodilators, including short and long-acting agents, first line, and careful consideration should be given as to whether an ICS is really needed. So where does that leave the clinician and the patient? How should we treat Tracey?

Does she need an ICS?

Tracey’s history is strongly suggestive of asthma and she has shown evidence of reversibility on spirometry. The BTS/SIGN guidelines state that people with asthma should be treated with an ICS,7 so the answer to this question is a straightforward ‘yes’. It would be inappropriate to leave Tracey’s reversible airways disease (i.e. asthma) untreated and an ICS is the treatment for asthma. The dose should be the lowest dose possible which treats the underlying inflammation and relieves symptoms, meaning that the patient rarely needs their short acting bronchodilator (SABA). BTS/SIGN recommends a total daily dose of 400mcg standard ICS or equivalent – i.e. Clenil (beclometasone) 200mcg bd, Pulmicort (budesonide) 200mcg bd, Flixotide (fluticasone) 100mcg bd or Qvar (fine particle beclometasone) 100mcg bd.

Does she need a bronchodilator?

In view of her ongoing irreversible airflow and her symptoms of COPD, Tracey is going to need a regular bronchodilator. An assessment of Tracey’s current symptoms and exacerbation history, based on the GOLD ABCD guidance on treatment options, puts Tracey into category B – she has regular symptoms but no history of an exacerbation of COPD in the past year. Category B patients should be offered a long acting bronchodilator – such as a long-acting beta2 agonist (LABA) and/or a long-acting muscarinic antagonist (LAMA) – for symptom relief. If she has a LABA, she can have a combination inhaler, which contains both ICS and LABA in one device. There are no devices that contain a combination of an ICS and a LAMA.

If she prefers a LAMA (which might be helpful for her productive cough6), she will need to have two separate devices. This might affect adherence and will also impact on the cost of her treatment if she pays for her prescriptions. A pre-payment certificate might then be worth considering, especially if she is also going to have a salbutamol inhaler to use on an ‘as required’ basis.

If Tracey opts for a LAMA to treat her COPD symptoms, she can choose from all available options. If the LAMA was to be used for her asthma (which on this occasion it is not) the only licensed option would be the Spiriva Respimat.

If necessary, Tracey could also have a low dose ICS plus a LABA/LAMA dual bronchodilator. Again, the ICS would be used to treat her asthma and the dual bronchodilator used to treat her COPD, reflecting the need to be creative in the approach to managing ACO, in the absence of any formal guidelines.

Combination inhalers (ICS/LABAs)

If Tracey opted for an ICS/LABA, the decision as to which combination treatment to try is, arguably, academic as none of them is licensed to use in ACO. Patient preference and ability to use the device should be key drivers in the decision making process, then. The important thing to remember is to keep the dose of the ICS low as this is only being used to treat the asthma component. Traditionally, higher doses of ICS/LABA combinations have been used in COPD management but these are not necessary in Tracey’s case as the ICS is not being used for her COPD but is instead only treating her asthma. Even ‘pure’ cases of COPD rarely, if ever, require high dose ICS/LABA combinations as the risk/benefit ratio is unfavourable.8,9

Triple therapy inhalers

There are two triple therapy inhalers on the market that contain an ICS, LABA and LAMA. Both are licensed to treat COPD only. Drug manufacturers will always advise prescribers not to use their treatments off-licence. In a general sense, however, guidelines on prescribing practice, including those for non-medical prescribers, state that off licence prescribing is permissible as long as there is no other option available and the patient is aware and agrees to use a treatment off licence.10 As always in this situation, the prescriber takes responsibility for advising and prescribing, and any decision should be documented carefully, reflecting the elements mentioned above.

SMOKING CESSATION

Possibly the single most effective intervention for Tracey in terms of preventing further deterioration of her condition, would be to support her with smoking cessation.11 Using motivational interviewing and cognitive behavioural therapy techniques, Tracey’s potential reasons for stopping should be identified and appropriate approaches to smoking cessation selected. As well as behaviour change strategies, pharmacological interventions such as varenicline, nicotine replacement therapy or, based on Public Health England advice, even vaping could be considered.12 She needs to understand the role that smoking has played in the development of her COPD and symptoms and understand the impact that quitting could have on future symptoms.

NON-PHARMACOLOGICAL MANAGEMENT

Tracey is likely to benefit from pulmonary rehabilitation and a referral should be made, depending on local referral guidelines. She should also be encouraged to eat a healthy diet and maintain regular physical activity as these have both been shown to improve lung health.6

MANAGING ACUTE EXACERBATIONS

Acute exacerbations of both asthma and COPD can be life threatening. Prevention is key and taking regular medication (ICS in asthma and ICS/LABA or LABA/LAMAs in COPD) have been shown to reduce the risk of flare ups.13 However, if an exacerbation does occur, changes in medication should be initiated. For both conditions, optimisation of bronchodilator therapy is the first step. Acute asthma should be treated with a high dose bronchodilator.7 The treatment of COPD exacerbations should begin with an increased dose of SABA and potential changes to the daily bronchodilator regime.6 In all cases of acute asthma, prednisolone should be given at a dose of 40-50mg a day for at least 5 days.7 In acute exacerbations of COPD (AECOPD) where breathlessness is the main problem, prednisolone should also be given at a dose of 40mg daily for at least 5 days.14 This means that the dose regimen is the same for both asthma and COPD exacerbations. With respect to antibiotics, these should not be given routinely to people with acute exacerbations of asthma.7 In AECOPD, antibiotics are recommended if the individual meets the Anthonisen criteria – increased dyspneoa, increased sputum volume, and increased sputum purulence.15

PATIENT EDUCATION AND SELF-MANAGEMENT

People with asthma should have written personalised asthma action plans (PAAPs) as should those with COPD. There is a range of opinion as to what should be included in these plans. BTS/SIGN says it is important that PAAPs are simple and straightforward. Asthma UK has downloadable PAAPs available from https://www.asthma.org.uk/ globalassets/health-advice/resources/ adults/adult-asthma-action-plan.pdf. The British Lung Foundation (BLF) offers free COPD information packs and self-management plans for health care professionals to give to people with COPD and which contain information about the condition itself as well as what to do if symptoms deteriorate. These are available from https://shop.blf.org.uk/collections/hcp.

Obviously the situation with education and self-management potentially becomes more complicated if the patient has elements of both conditions, as we have seen with Tracey. Patient education is important if self-management skills are to be taught effectively but clinicians may find themselves wondering which approach to take and how to make the information as simple as possible. Put simply, when it comes to dealing with ACO, the history should be examined to see which disease seems to be the dominant feature of how the patient presents and then the guidance for that condition should be followed in the main, adjusting information sharing to cover the other condition as necessary.

READ CODING AND TEMPLATES

There are now Read codes which reflect a diagnosis of ACO. Patients can be coded as ‘asthma with fixed airways disease’ or as ‘asthma-COPD overlap’. In terms of completing QoF templates, it is possible to complete each template (asthma and COPD) according to how that aspect of the disease presents. So if an individual’s breathlessness is a reflection of the COPD element of their condition rather than the asthma, it would be right to say in the asthma template that their condition causes them symptoms only once or twice a week, for example. However, this also requires some ‘free-texting’ to explain what is actually happening in each individual patient’s circumstances. Free-texting is also important when explaining treatment decisions as indicated above.

SUMMARY

Although asthma and COPD are different conditions with different pathological processes, studies suggest that there is some overlap between the conditions and so some people will have elements of both. Careful history taking, assessment and management should ensure that each individual is treated appropriately. There are no guidelines specifically written for ACO and clinicians will therefore need to use their clinical judgement, knowledge and experience to identify the most appropriate interventions for each individual and to support patients with shared decision making. Off licence prescribing is permissible but should only be implemented when there are no licensed options available and with the patient’s full understanding and agreement. Referral to members of the multi-disciplinary team – e.g. smoking cessation and pulmonary rehabilitation – should be used to ensure the individual gets the best quality of care aimed at improving their health now and in the long term.

REFERENCES

1. Chatkin J M, Dullius CR. The management of asthmatic smokers. Asthma Research and Practice 2016;2:10. http://doi.org/10.1186/s40733-016-0025-7

2. Gibson PG, Simpson JL. The overlap syndrome of asthma and COPD: what are its features and how important is it? Thorax 2009;64:728–735

3. Silva GE, Sherrill DL, Guerra S, Barbee RA. Asthma as a risk factor COPD in a longitudinal study. Chest 2004;126:59–65.

4. George L, Brightling CE. Eosinophilic airway inflammation: role in asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Therapeutic Advances in Chronic Disease 2016;7(1), 34–51. http://doi.org/10.1177/2040622315609251

5. GINA Report, 2017. http://ginasthma.org/2017-gina-report-global-strategy-for-asthma-management-and-prevention/

6. GOLD 2018 http://goldcopd.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/GOLD-2018-v6.0-FINAL-revised-20-Nov_WMS.pdf

7. BTS/SIGN British guideline for the management of asthma, 2016. https://www.brit-thoracic.org.uk/document-library/clinical-information/asthma/btssign-asthma-guideline-2016/

8. Crim C, Calverley PM, Anderson JA, et al. Pneumonia risk in COPD patients receiving inhaled corticosteroids alone or in combination: TORCH study results. Eur Respir J 2009;34(3):641–647

9. Ernst P, Saad N, Suissa S. Inhaled corticosteroids in COPD Eur Respir J 2015;45: 525-537

10. MHRA. Drug safety update 2009; 2(9):6. https://www.gov.uk/drug-safety-update/off-label-or-unlicensed-use-of-medicines-prescribers-responsibilities

11.NICE. Smoking: supporting people to stop, 2013. https://www.nice.org.uk/ guidance/qs43

12.Public Health England. Evidence review of e-cigarettes and heated tobacco products, 2018 https://www.gov.uk/ government/ uploads/system/uploads/ attachment_data/ file/680964/Evidence_ review_of_e-cigarettes _and_heated_ tobacco_products_ 2018.pdf

13.Bostock B. Management of acute exacerbations of COPD in primary care. Practice Nurse 2017;47(12):22–26. http://www.practicenurse.co.uk/index.php?p1=articles&p2=1613

14.Leuppi JD, Schuetz P, Bingisser R, et al (2013) Short-term vs Conventional Glucocorticoid Therapy in Acute Exacerbations of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease: The REDUCE Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA 2013;309(21):2223–31

15.Anthonisen NR, Manfreda J, Warren CP, et al. Antibiotic therapy in exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease Ann Intern Med 1987;106:196–204

Related articles

View all Articles