Helping nurses prepare for uncertainties in practice

Andrée le May PhD BSc (Nursing Studies) PGCE(A), School of Health Sciences, University of Southampton | Ann McMahon PhD MSc (Nursing) BSc (Nursing), Nursing and Health Care School, University of Glasgow | Alison Twycross PhD RN, University of Birmingham | Elaine Maxwell PhD, London South Bank University, London

Practice Nurse 2025;55(6):24-28

Based on a series of case studies of patients with long COVID, the authors developed a framework to help GPNs feel more confident in caring for patients in situations such as pandemics, or when medical diagnoses are unclear or unavailable

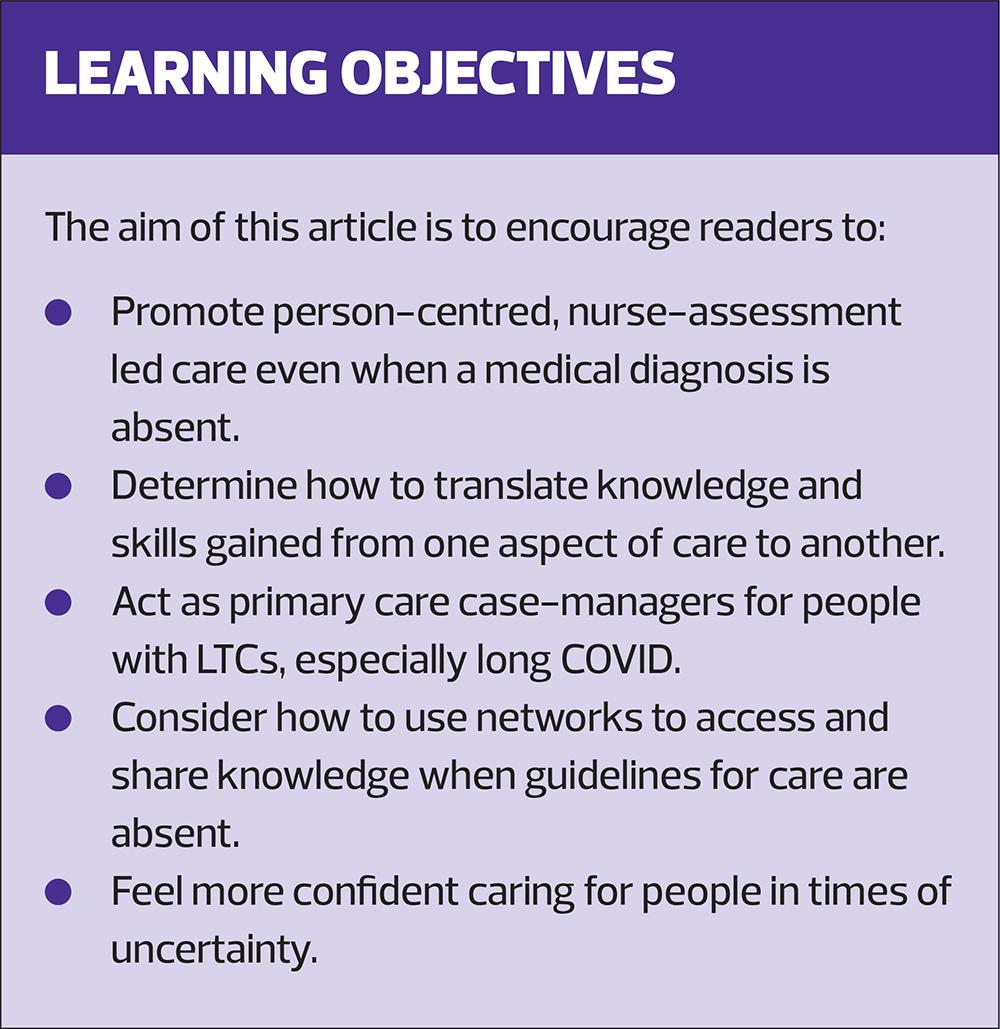

Three years ago, we – four nurse researchers, educators, and practitioners – began discussing the important but often overlooked role of nursing in caring for people with long COVID. Despite nurses' extensive experience supporting individuals with LTCs, there was little guidance on effective care as long COVID emerged. Frustrated by this gap, we secured limited funding from Health Education England to explore nurses’ roles and perspectives in managing long COVID. Based on our findings, we have developed a series of best practice ideas and identified 10 key elements of care to better prepare nurses for future pandemics and caring for patients with unknown conditions or who have no definitive diagnosis.

WHAT WE DID

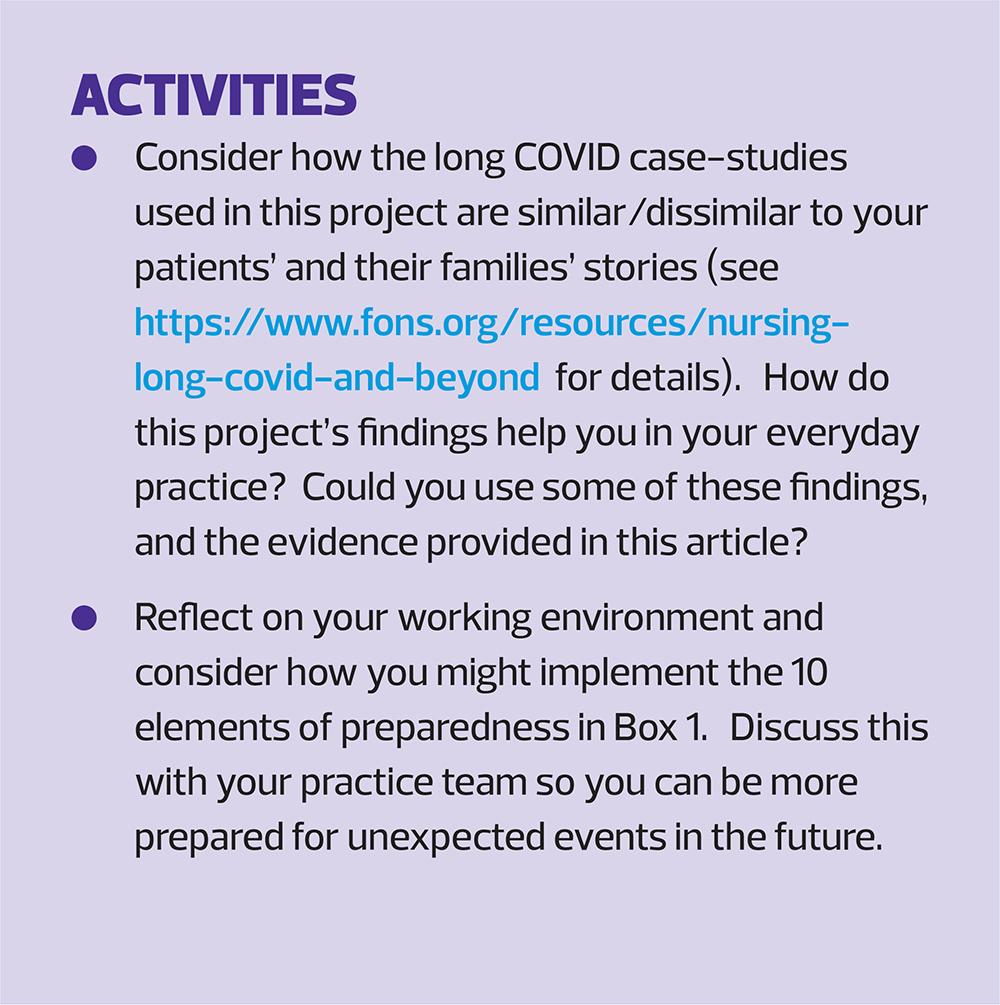

First, we interviewed three people with long COVID and constructed three very different case-studies from their experiences (see https://www.fons.org/resources/nursing-long-covid-and-beyond). We then invited selected clinical nurse specialists who care for people living with long-term conditions to review our case studies to see what we could learn from their experience and expertise, and asked them to provide evidence to support their ideas. This group included specialists in respiratory nursing, neurological nursing, occupational health nursing, rare-disease nursing, cancer nursing and mental-health nursing. We then collated this information to form a clear set of ideas on the distinct nursing contribution to care for people with long COVID, which could be used in multiple settings and complement the consultation guide developed by Janes and colleagues.1

WHAT WE FOUND

1. Living with uncertainty

Long COVID is now a recognised condition, and we have a better understanding of the trajectory of symptoms, underlying mechanisms and treatments to improve people’s health. However, it still exhibits a level of uncertainly as patients do not all present in the same way.2 The symptoms of long COVID are heterogeneous, multisystemic and can change over time, complicating the lives of those living with it.3 In addition, the duration of long COVID varies widely.4Long COVID patients, like many people with a long-term condition (LTC), live with a measure of uncertainty that impacts their daily living, mental health and well-being.5 The lack of awareness among the public and health-care professionals along with a lack of testing also mean that many people have unrecognised long COVID.

The nurse’s role is to support patients living with this uncertainty to help them to self-manage their condition, and to enhance their well-being and quality of life.6,7 This starts with listening to their story, their diagnosis – if they have one – and finding out how it affects them, including any loss of identity and role (both professional and personal). Other support includes considering mental health referral, improving access to psychological therapies, signposting people to support from the third sector and/or spiritual support – being careful not to imply that you think all the patient’s symptoms are ‘in their head’.Peer support groups may also be helpful.

NICE8 suggests the following:

- Discussing with the person (and their family or carers, if appropriate) the options available and what each involves.

- Using shared decision-making to agree what support and rehabilitation is needed, including how and when it should be provided.

- Providing advice and information on self-management.Managing specific symptoms appropriately.

- Considering social prescribing options and psychotherapeutic support from other practitioners or external organisations such as the ME Association.

2. Not being listened to – ‘people don’t understand because this is new’

Acknowledging the importance of lived experience is vital in this context because the person is the expert in their own difficulties.9 Listening helps them to feel supported and believed and helps others understand what they are experiencing, enables partnerships to develop and nurses to act as trusted advocates.

In rare or emergent diseases, people may have spent years not being believed, seeing various specialists, and receiving several misdiagnoses.In these instances the opportunity to share their stories is hugely important.It is important that enough time is provided for discussion. Support might include communicating the specific patients directly with specialist services, and speaking up for a patient who may not be able to do so themselves.

3. Impact on family and carers

Caregivers play an essential, often unseen or unrecognised, role in caring for people with LTCs.10 Nurses are in a unique position to validate their role as carers and lessen the impact the illness has on their lives too.10 Often, informal care givers are not adequately prepared or trained for this complex role.11

Caregivers’ needs should always be considered,12 for example, by using a tool such as CSNAT (Carer Support Needs Assessment Tool). This enables carers to identify and prioritise where they need more support.13This can be used alongside the Support Needs Approach for Patients (SNAP) tool which enables patients to identify and express their unmet support needs.14

4. Impact on partners, children, immediate and extended family

It is important to focus on the network of relationships supporting people with long-term illnesses. This may include providing psychological and emotional support for partners.15

Support to help children understand what is happening, and any behavioural challenges, when a parent has chronic illness may also be necessary, and may include liaising with nursery or school staff/health visitors or school nurses/social services and the GP.There may be issues for the children if the parents are not able to care for them adequately, so this needs careful assessment and handling by the health-care team.For an example, see Sheffield Children Safeguarding Partnership at https://www.safeguardingsheffieldchildren.org/.

5. ‘Blocking out what has happened’

Research shows trauma symptoms can occur following COVID infection,16 and may result in attempts to block out negative experiences and/or deal with the traumatic aspects of being unwell and having to make life-changing alterations. Such cognitive avoidance may perpetuate psychological difficulties associated with the traumatic experience. Taking a trauma-informed approach may be beneficial because it acknowledges the existence and psychological consequences of traumatic experiences.17

6. ‘Learning how to create a new version of me due to long COVID’

Re-defining and adapting to the challenges experienced are important – nurses can have a role in this, but they should tread carefully. The nurse's role should focus on facilitation and support for self-management, through co-creating self-management programmes, interventions, or services for people with long COVID.18 There might also be opportunities for the person to become involved with educating health-care professionals about long COVID.19

Returning to life as it was before COVID-19 may not be achievable for everyone with long COVID. People need to grieve what they have lost and may need psychological support to move forward. This needs sensitive handling by all healthcare workers as information regarding prognosis, management and recovery times remains sparse. Physical management of symptoms is as important as emotional support, and nurses need to keep up to date with new approaches so they can discuss them with patients and families. The Living Well with a Disability website may be useful – see https://www.helpguide.org/wellness/health-conditions/living-well-with-a-disability

Referral to psychological services is important here too.

7. Financial consequences

Financial consequences of long COVID may include reduced income, changed employment status or ability to work in the same role without modification, and needing adaptations to the home environment.Nurses should ask about these concerns and refer to the Citizens’ Advice Bureau /local benefit advice/supportive agencies/charities.

8. Pressure to spend on treatment

People with LTCs often look for ways to improve their health and well-being. However, some purported treatments and management strategies for long COVID have not been studied, and are risky, expensive and do not have clear benefits. Helping patients assess the benefits (and costs) of such approaches may be part of a consultation. In these situations nurses may use self-management/patient activation techniques to identify priorities,20 and strengthen decision-making as well as referral for more specialist advice.

MANAGING SYMPTOMS

Undertake a comprehensive holistic assessment

Holistic assessment is at the centre of general practice nursing and should include advice on:

- Ways to self-manage symptoms, such as setting realistic goals.

- Energy conservation, pacing, planning and prioritising.

- Who to contact if they are worried about symptoms or need support.

- Sources of advice and support, including support groups, social prescribing, online forums and apps, such as the ‘My Long COVID’ app.8

Encouragement to keep a symptom diary may be helpful too.

Impact of physical symptoms on mental health

People may experience many symptoms which have a negative impact on their mental health. Often people living with LTCs will experience some form of mental health difficulty, so it is important to carry out mental health assessments, refer appropriately and evaluate the effectiveness of any supportive measures.

Using an integrated approach which combines medical, psychosocial, and alternative approaches and draws from learning in other areas (e.g., fibromyalgia, chronic fatigue syndrome) may prove a useful strategy.21

Individualised treatment priorities may include managing energy levels, maintaining mood, and developing coping skills. This may include cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT), if available, and if it has not been tried before.

It might also be useful to develop a personal WRAP (wellness, recovery, action, plan) in partnership with the person. WRAPs promote self-management, are widely used within mental health services, can help recovery, and promote long-term well-being.22

Feelings of despondency

Feelings of despondency need to be acknowledged, and motivational interviewing may be helpful in reducing them.

However, sensitive screening is important here too, to rule out depression, since people use different words and terminology to describe how they feel. If a patient says they are depressed, it might be useful to explore what the person thinks about mental health generally and their own mental health. It is also possible the person feels they are being dismissed because people think they have mental health difficulties, so seeking clarification would be useful.

Screening needs to be done compassionately using a valid and reliable screening tool e.g. PHQ9,23 or the 5 Areas Assessment.24

There are several support tools for people with sub- or non-clinical mood difficulties which might be useful (e.g. Problem-Solving Therapy, Behavioural Activation, CBT-based self-help).25

Monitoring and managing fatigue

Some people with LTCs experience altered sleep patterns, crushing tiredness and post-exertional malaise.

Advice may be informed by other conditions where chronic fatigue occurs and referral for specialist assessment may be appropriate.

Post-exertional malaise and/or post-exertional symptom exacerbation may limit what they can do to aid recovery.

Providing supportive sleep hygiene advice is important. The Sleep Council has many useful resources, including Practical sleep tips for adults, available at https://thesleepcharity.org.uk/information-support/useful-resources/.

Titrating and monitoring responses to interventions to promote sleep and alleviate fatigue are important, so a symptom/response diary could be useful.

Encourage patients to keep a diary of what makes fatigue worse, better or makes no difference over the course of 3-6 weeks. The diary should also include changes in temperature, weather, food intake, alcohol intake, exercise etc.Depending on findings, participation in a fatigue management course may be suggested (e.g. the MS Society’s online workshop).

Consider carrying out full blood screening to eliminate other possible causes of fatigue, e.g, B12, folate, low iron, and check Vitamin D levels.There is a link between low vitamin D levels, fatigue and multiple sclerosis. Consider referring for a full neurological assessment, testing power, resistance, strength and questioning about any changes in physical symptoms, and sensory symptoms.

Refer to other professionals e.g. occupational health, physiotherapy, occupational therapy, nutritionists as required.

NAVIGATING THROUGH OTHER SERVICES

People with long COVID still struggle to access healthcare.26 They continue to experience systemic barriers to accessing care and challenges navigating the unknowns of long COVID.27 Nurses can act as care system navigators, supporting people with long COVID – and other LTCs – and their carers, to navigate the complexities of healthcare systems. Nurses also may have a role as case managers, chasing up referrals from other services, disciplines and specialist nurses.

Nurses are skilled listeners, and it is important to listen to and validate the experiences of people with long COVID.They need support to process the emotional landscape of their condition, their changing limits to daily living, grief and loss of former identity and learning to cope with persisting symptoms.28

Developing a sound relationship is vital. Empathy and active listening are essential. Where care is undertaken by a multidisciplinary team (physiotherapist, social worker, occupational therapist), the nurse can help to navigate patients through such services as well as support groups.

When patients have concerns about their care, nurses should direct them to the local Patient Advice and Liaison Service (PALS) or Healthwatch for advice.

BEING BETTER PREPARED

One thing that came out of our findings was that nurses, people with long COVID, and their family and carers were constantly facing uncertainty and had very little help.So, we asked ourselves, what learning could we add from colleagues who may have nursed people with similar uncertain conditions?

We considered the experience of nursing in relation to HIV/AIDS as an example. So profound was the early impact of HIV that the lack of interventions at the outset of the disease led to significant levels of mortality. As time passed and new interventions, primarily pharmaceutical, were developed, the disease transitioned from an acute life-threatening one, into a long-term condition with varying degrees of associated morbidity. We thought there were interesting parallels with the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic, as well as notable differences. While HIV/AIDS has transitioned from an acute into a long-term condition, COVID-19 affected people on multiple levels, from acute and life threatening, through to mild, and, at face value, seemingly insignificant; and from relatively short-term, through to a long-term condition affecting multiple organs and the body’s ability to function effectively, physically, mentally and socially.

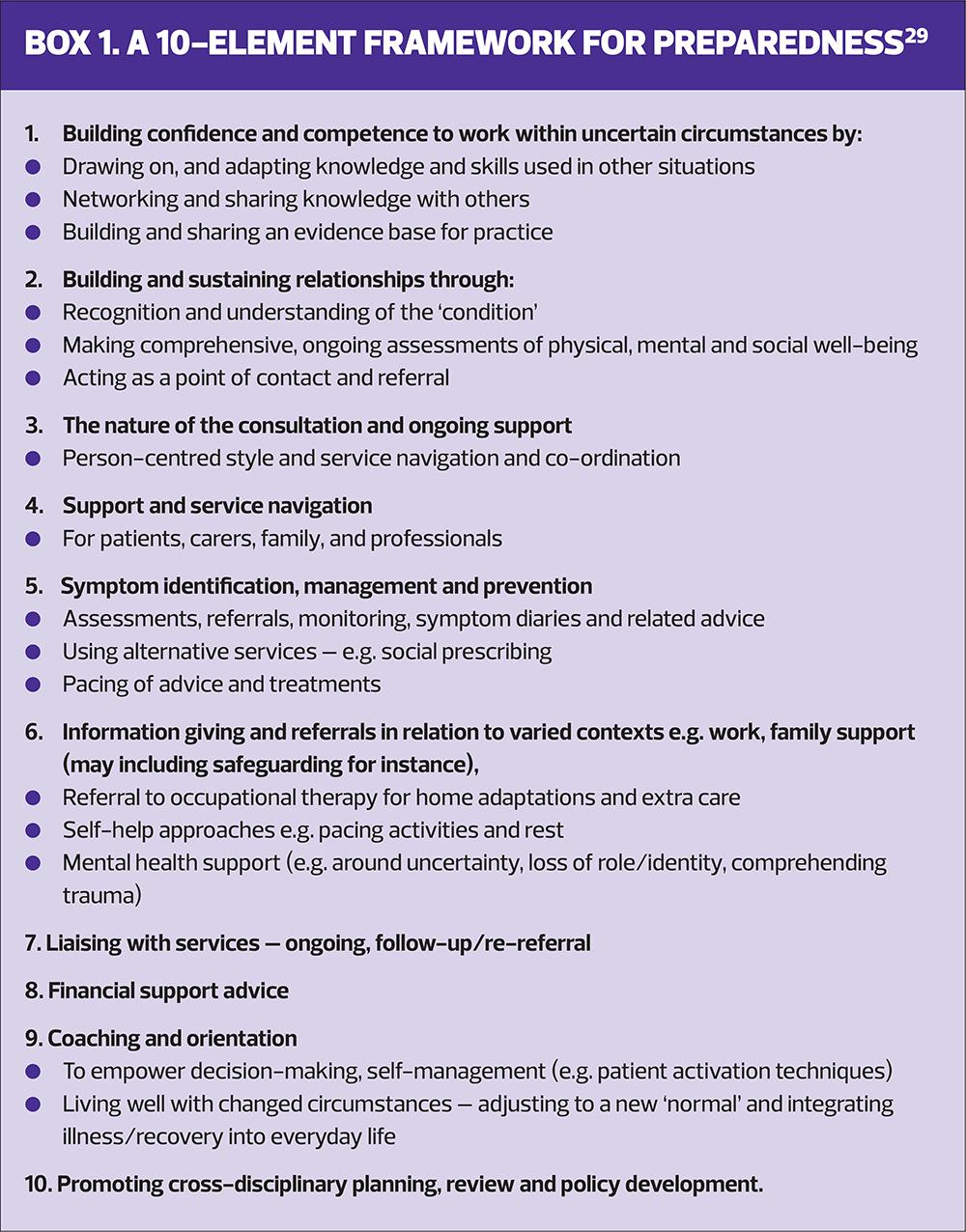

The findings from this long COVID work and our reflections on how nursing has previously dealt with uncertainty enabled us to produce a framework to inform nurses’ responses to new conditions of unknown origin and unknown trajectory (Box 1). We then sent this to a group of experts from varying nursing specialities for validation.Having such a framework may help GPNs to deal better with uncertainty and so feel more confident in providing consistent and coherent care in situations such as pandemics, or when medical diagnoses are not clear or available.

HOW COULD OUR FINDINGS BE USED

At the personal level, a nurse can establish and sustain a person-centred, therapeutic relationship with the individual, and their carers and family. This is possible through a rolling, comprehensive assessment and evaluation which identifies needs and helps provide support when dealing with uncertainty. Such a relationship can help a person to live well with changing physical, mental and social challenges and the uncertainties that this brings.

At a system level, a nurse can help patients and their families and carers to navigate health, voluntary and social-care services and they can act as a case manager liaising across professional networks. In principle, they could also make a significant contribution to cross-discipline, cross-organisational and cross-agency patient records detailing assessments, interventions and evaluation of what works. But we know that, in reality, we are some distance away from such integrated systems and approaches being adopted in practice. Learning how to enable such an approach to function universally should be a system-wide part of any preparedness agenda. Lessons may be learned from colleagues working in multiple areas including, for example, public health and hospital discharge/transition planning and delivery. When working optimally, such systems would not only detail the numbers of people experiencing symptoms, but also the nature and severity of their symptoms, and how they are being managed and evaluated. This could also facilitate peer support to others and create an evidence base for practice and policy.

At the policy level (regional, national and/or international), nurses can work through their networks to share intelligence and data, drawing on lived experience, assessing interventions and outcomes, and identifying patterns in the care experience which can be used by others to create wider policy briefings.

Through these processes nurses can collectively develop and grow a model of care and an evidence base.

RESOURCES

- Long-term effects of long COVID https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/long-COVID/

- Long COVID: symptoms, tests, treatment and support https://www.bhf.org.uk/informationsupport/heart-matters-magazine/news/coronavirus-and-your-health/long-COVID

- Different presentations of long COVID https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1876034125003430

- Motivational Interviewing https://www.health.org.uk/reports-and-analysis/reports/training-professionals-in-motivational-interviewing

- Managing fatigue https://www.mssociety.org.uk/about-ms/signs-and-symptoms/fatigue/managing-fatigue

- Pacing https://www.rcot.co.uk/learn-about-occupational-therapy/ot-advice/lift-up/energy

- Peer support Day HLS. J Medical Internet Research; 2022 https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9128729/; Somerton A, Jeffrey H. J Health Psychology; 2024 https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/13591053241296184

- Returning to Work https://www.som.org.uk/sites/som.org.uk/files/Long_COVID_and_Return_to_Work_What_Works.pdf

- Financial consequences Rhead R, et al. J Epidemiology & Community Health; 2024 https://jech.bmj.com/content/78/7/458

REFERENCES

- Janes G, Chesterton L, Overton C, et al. Codesign of a shared consultation guide for managing long COVID in adults. Nursing Times 2025;121:6.

- Astin R, Banerjee A, Baker, et al. Long COVID: mechanisms, risk factors and recovery. Exp Physiol 2023;108(1):12-27

- Greenhalgh T, Sivan M, Perlowski A, et al.Long COVID: a clinical update. Lancet 2024;404(10453):707-724

- Donald J, Bilasy S E, Yang C, et al. Exploring the complexities of long COVID. Viruses 2024:16(7):1060

- Brown A, Hayden S, Klingman K, et al. Managing uncertainty in chronic illness from patient perspectives. J Excellence Nurs Healthcare Pract 2020;2(1):1.

- Entwistle VA, Cribb A, Owens J. Why health and social care support for people with LTCs should be oriented towards enabling them to live well. Health Care Analysis 2018;26:48-65

- McAllister M, Dunn G, Payne K, et al. Patient empowerment: the need to consider it as a measurable patient-reported outcome for chronic conditions. BMC Health Services Res 2012;12:1-8.

- NICE – Clinical Knowledge Summaries. Long-term effects of coronavirus (long COVID); 2022. https://cks.nice.org.uk/topics/long-term-effects-of-coronavirus-long-covid/

- Gorna R, Macdermott N, Rayner C, et al.Long COVID guidelines need to reflect lived experience. Lancet 2021;397(10273):455–457.

- Knowles S, Combs R, Kirk S, et al. Hidden caring, hidden carers? Exploring the experience of carers for people with long‐term conditions. Health Soc Care Comm 2016;24(2):203-213

- Zavagli V, Raccichini M, Ercolani G, et al. Care for carers: an investigation on family caregivers’ needs, tasks, and experiences. Transl Med UniSa 2019;19:54-59

- Marin-Maicas P, Corchon S., Ambrosio, L. et al. Living with long term conditions from the perspective of family caregivers. A scoping review and narrative synthesis. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2021;18(14):7294

- Ewing G, Grande G. National Association for Hospice at Home. Development of a Carer Support Needs Assessment Tool (CSNAT) for end-of-life care practice at home: a qualitative study. Palliat Med 2013;27(3):244-256

- Gardener AC, Ewing G, Mendonca S, Farquhar M. Support Needs Approach for Patients (SNAP) tool: a validation study. BMJ Open 2019; 9(11):e032028

- Deek H, Hamilton S, Brown N, et al. Family-centred approaches to healthcare interventions in chronic diseases in adults: a quantitative systematic review. J Adv Nurs 2016; 72( 5):968– 979

- Salehi M, Amanat M, Mohammadi M, et al. The prevalence of post-traumatic stress disorder related symptoms in Coronavirus outbreaks: A systematic-review and meta-analysis. J Affect Disord 2021; 282:527-538

- Javakhishvili JD, Ardino V, Bragesjö M, et al. Trauma-informed responses in addressing public mental health consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic: Position paper of the European Society for Traumatic Stress Studies (ESTSS). Eur J Psychotraumatol 2020;11(1):1780782

- World Health Organization. Support for rehabilitation: self-management after COVID-19-related illness; 2020. https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/support-for-rehabilitation-self-management-after-covid-19-related-illness

- Fossey E, Bonnamy J, Dart J, et al. What does consumer and community involvement in health-related education look like? A mixed methods study. Adv Health Sci Educ 2024;29:1199-1218

- Hibbard JH, Stockard J, Mahoney ER, et al. Development of the Patient Activation Measure (PAM): Conceptualizing and Measuring Activation in Patients and Consumers. Health Services Res 2004;39:1005-1026

- Roth A, Chan PS, Jonas W. Addressing the long COVID crisis: integrative health and long COVID. Glob Adv Health Med 2021;10: 21649561211056597

- Canacott L, Moghaddam N, Tickle A. Is the Wellness Recovery Action Plan (WRAP) efficacious for improving personal and clinical recovery outcomes? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychiat Rehabil J 2019;42(4):72

- Costantini, L., Pasquarella, C., Odone, A. et al. Screening for depression in primary care with Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9): A systematic review. Journal of affective disorders, 2021; 279, p 473-483

- Williams C, Garland A. A cognitive–behavioural therapy assessment model for use in everyday clinical practice. Adv Psychiatr Treat 2022; 8(3):172-179

- Hao X, Jia Y, Chen J, et al. Subthreshold Depression: A Systematic Review and Network Meta-Analysis of Non-Pharmacological Interventions. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat 2023;19:2149–69

- Turk F, Sweetman J, Chew‐Graham CA, et al. Accessing care for Long Covid from the perspectives of patients and healthcare practitioners: A qualitative study. Health Expect 2024;27(2):e14008

- Koc HC, Xiao J, Liu W, et al. Long COVID and its Management. Int J Biologic Sci 2020;18(12):4768

- Kennelly CE, Nguyen AT, Sheikhan NY, et al. The lived experience of long COVID: A qualitative study of mental health, quality of life, and coping. PloS one, 2023;18(10):e0292630

- le May A, McMahon A, Twycross A, et al.Nursing on the front foot.Editorial.Evidence Based Nursing https://doi.org/10.1136/ebnurs-2025-104418

Related articles

View all Articles