How occupational therapists can ease workload in general practice

Cassie Ludlam

Cassie Ludlam

BSc (Hons) MRCOT

Occupational Therapist

St Thomas Medical Group, Exeter

Elizabeth Gillam

BSc (Hons) MRCOT

Occupational Therapist

Pinhoe and Broadclyst Medical Practice, Exeter

Practice Nurse 2021;51(7):22-25

Having an occupational therapist on the practice team can speed up referrals and ensure that patients – particularly those with frailty – can be assessed promptly and appropriate levels of support provided

We each have our own hobbies, routines, skills and responsibilities. Coupled with our beliefs and experiences, this is what makes us who we are. These factors play a role in the daily meaningful activities we carry out and these are what Occupational Therapists (OTs) describe as ‘occupations’.1 Occupational therapy provides practical support to empower people to facilitate recovery and overcome barriers preventing them from doing the activities (or occupations) that matter to them.2

OTs are trained to work across all ages, with those who have any physical or mental health condition. However, once qualified, many OTs prefer to focus on a specialist area. In primary care, occupational therapy is currently focusing on three areas: frailty, mental health and vocational rehabilitation.3,4 OTs complete holistic, person centred assessments, which are completed both face to face within patient’s homes and by phone. OTs undertake thorough and detailed assessments, which can help other healthcare professionals in general practice to have a deeper understanding of their patients.5

WHY PRIMARY CARE?

Due to workload pressures within primary care, it has been widely recognised that occupational therapy could play a key role in supporting GPs.5-10 This can be through focusing on prevention, which is essential in supporting individuals to better manage their long term conditions.11

The average cost for social care to support a patient with fragility is £2,895 per year, compared to £321 per year for those who are not frail.12 OTs use a ‘strengths based approach’ as recommended in the Care Act, 2014,13 to empower patients to support themselves. They can encourage those with a degree of frailty to better manage their long term conditions and promote independence. In addition to this, OTs can provide advice and assistance in falls prevention, which can help to reduce the risk of admissions to hospital.14,15 OTs can also help people who are socially isolated to access voluntary and community services, which can help to reduce loneliness, which is a growing problem and has been linked to multiple health issues.16,17

General practice is the ideal setting for multidisciplinary working. Patients are well known to the GPs, practice and district nurses, enabling them to identify and address problems early, and refer patients directly to occupational therapy. Equally, OTs working in primary care benefit from being able to communicate quickly and directly with GPs and practice nurses, helping to streamline services.5

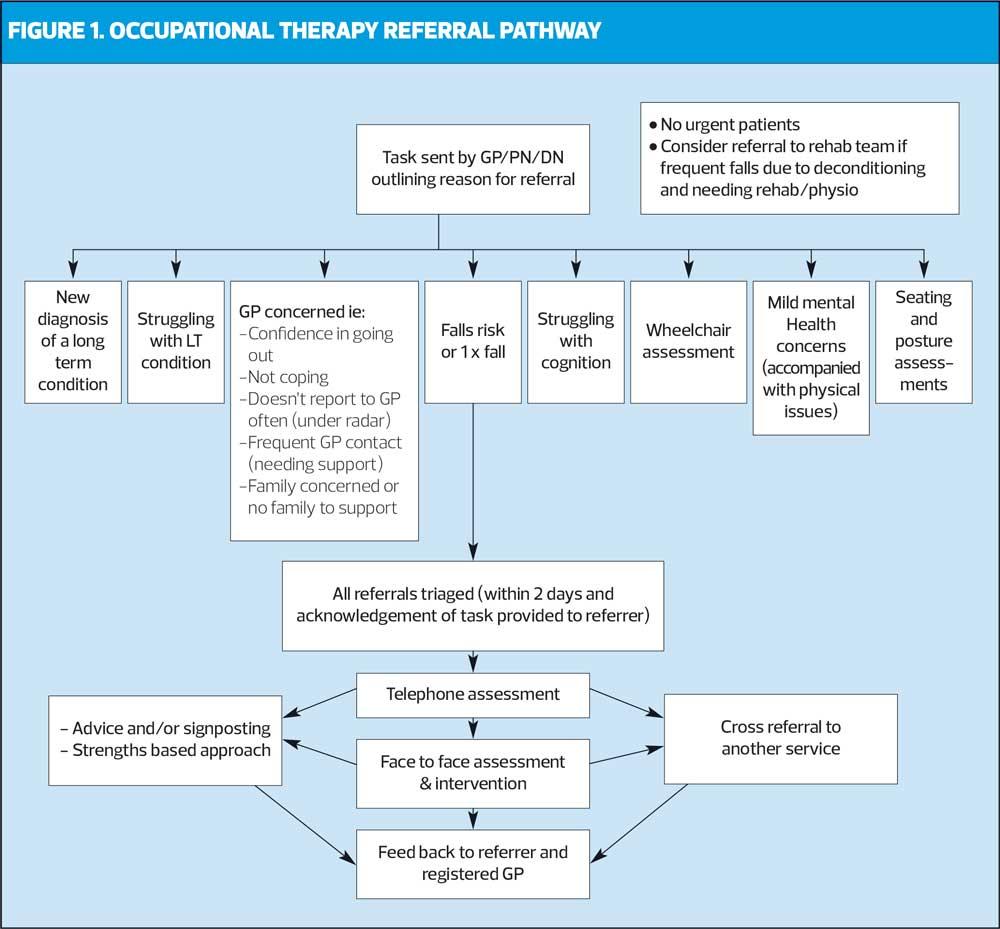

The authors, Cassie Ludlam and Elizabeth Gillam, are two OTs who work in primary care, in two separate localities in Devon. Their focus is on adults who have a degree of frailty or are living with a long term condition. The referral pathway they currently use is shown in Figure 1.

In a recent service review, both doctors and practice nurses commented that working in the same building as the OTs has enabled them to refer patients quicker and more easily. Another advantage is that the OTs can enter notes directly onto the patient’s records for immediate viewing by the practice staff. The value placed on the service is demonstrated by the feedback below:

- ‘…has made a real difference to have someone so knowledgeable on site and takes work away from GPs, freeing us up for other clinical work’

- It has been very useful ‘to have a colleague who is able to perform a holistic assessment and deal with all the issues relating to frailty’

- ‘…appreciate being able to refer “complicated” patients where much of the need is non-medical and requires knowledge of and contact with other agencies. OT clearly has an in depth knowledge and good relationships with the right people’

- ‘What has impressed me is the thoroughness of your approach to patients’ issues. You have escalated problems when you have recognised that medical input may be needed. You have also taught me a lot about the current skills and range of what an OT is competent to deal with.’

Practice nurses’ knowledge of patients who visit regularly provides the opportunity to identify concerns or issues which could be addressed by OTs before further clinical problems arise. These patients may have difficulties managing activities of daily living at home, such as showering, getting into or out of bed, or they could be at risk of pressure sores. OTs are regularly involved in supporting patient’s pressure care needs in the community, which can involve advice on seating and posture to prevent pressure sores.19,20 Being able to easily refer to an OT within the practice could improve patients’ long term health and wellbeing and prevent deterioration.

CASE STUDY 1

Patricia is a 68-year-old lady, with established dementia who lives alone with her dog, Pepper. Concerns were raised by her GP about deteriorating memory and how this may be affecting her ability to cope with everyday life. Patricia was independently mobile without aids, but appeared slightly frail. She was receiving a package of care once every morning, to prompt showering, medication and breakfast. Following a face-to-face occupational therapy assessment, and discussion with Patricia’s daughter on the phone (with Patricia’s consent), the following concerns were identified:

- Patricia followed a vegan diet but sometimes forgot to eat and drink, resulting in her feeling fatigued.

- Patricia suffered with osteoarthritic pain in her hip. Medication was already in a blister pack and carers prompted her morning paracetamol, but she was at risk of forgetting to take her tablets every four hours, or she would take too many.

- She enjoyed walking Pepper daily, but there were concerns about her remembering to take the dog out. Her daughter also mentioned that she had got lost when going out before.

- Patricia was struggling to shower due to having limited places to hold onto when climbing over the edge of the bath.

- Patricia had begun to feel increasingly low in mood, as other than her daughter (who works full time) and the morning carers, she did not feel that she had any social contact with anyone.

With full consent from Patricia and collaboration with her daughter, the following measures were implemented:

- Advice on diet, including increasing Patricia’s protein source. The advice was written down for Patricia and also discussed with her daughter and carers.

- An increase in her package of care to twice daily support, to prompt Patricia about food, fluids and medication.

- Implementation of the Age UK Service visiting daily (in-between the carer visits), to support with befriending and company when walking the dog. Volunteers could also then check Patricia had eaten and had a drink while they were there and check she had taken her medication.

- Technology-enabled care was purchased by the daughter, following advice from the OT, which comprised:

- A GPS tracker device which was attached to Patricia’s keyring to allow her daughter to locate her if she got lost

- A talking reminder clock was purchased to support Patricia with remembering to eat, drink and take medication, and a bottle that would light up to remind her to drink regularly

- A floor to ceiling pole was installed in the bathroom to promote safety when Patricia was climbing over the bath.

All of the above interventions directly benefited Patricia’s health and wellbeing, promoting a healthier diet, increased social interaction, reduced anxiety for her and her daughter and increased her safety.

CASE STUDY 2

Percy is 57 and lives in a rented four-bedroom cob cottage with his wife and three teenage daughters. He was seeing the practice nurses twice a week to dress his leg and foot following a skin graft. He was referred to OT because he was having difficulties managing at home. Percy was a local councillor, who volunteered at his daughter’s school and used to do all cooking for the family. Percy had type 2 diabetes and a BMI of 35.1 kg/m2. He has found it increasingly difficult to manage his activities of daily living prior to his skin graft.

From the occupational therapy assessment, the following concerns were noted:

- Percy used crutches to get around in the property because of the limited space and uneven flag stone floor

- The property has a number of steps to access each room. Percy had to crawl up a spiral staircase to access his bedroom. There was an additional straight staircase, but Percy had to go through his daughter’s bedroom to get to it.

- Percy’s room had an en-suite with toilet and a bath, but he had to strip wash and was unable to wash his hair as he could not get his leg wet and had difficulty getting into the bath.

- The property did not have working heating, so Percy sat in a chair, with blankets to keep warm, for long periods. This increased his risk of developing pressure sores.

- Percy’s leg wounds leaked on the bed at night, causing him anxiety. And because of this, his wife slept in their daughter’s room and one of the daughters slept downstairs on the sofa.

- The downstairs toilet was out of use due to a leak and had poor access. If Percy needed to use the toilet when he was downstairs, he had to use a urine bottle or an empty plastic container in the lounge.

- Percy’s daughters were home schooling because of COVID-19. This meant he spent all of his time in his bedroom alone during the day so not to interrupt their study, because they had to leave the room if he needed the toilet.

- Because his skin graft caused occasional swelling, Percy had bought slippers that were two sizes larger than usual – but this also meant that when his feet were not swollen, the slippers were too loose and put him at risk of tripping.

With agreement from Percy and his wife, the following interventions were suggested and completed:

- Advice to use bed sheet incontinence pads under his leg.

- Suggestion that Percy should switch his bedroom with one of his daughters so that he could use the alternative straight staircase.

- A supporting statement was provided for their landlord, regarding adapting the downstairs toilet door.

- A request, with supporting evidence, was made to the landlord to repair the heating, to support Percy with his recovery.

- A swivel bather was ordered to allow access into the bath, so Percy could sit on it to strip wash while keeping his wound dry.

- Advice on purchasing a ‘no rinse’ shampoo cap.

- Advice and seated exercises to reduce Percy’s pressure sore risk.

- Advice and support in obtaining appropriate footwear with Velcro fastenings, to help reduce falls risk.

- Advice provided around using a perching stool to cook.

CONCLUSION

Primary care is a new area of practice for occupational therapy, which the authors are both excited to be a part of. They have been able to combine their areas of expertise, share ideas and look forward to developing their services.

REFERENCES

1. World Federation of Occupational Therapy. Definition of Occupational Therapy; 2010 https://www.wfot.org/resources/definitions-of-occupational-therapy-from-member-organisations

2. Royal College of Occupational Therapists. Occupational therapy in primary care. https://www.rcot.co.uk/occupational-therapy-primary-care

3. NHS Health Education England. Occupational Therapists in primary care; 2019 https://www.hee.nhs.uk/our-work/primary-care/occupational-therapists-primary-care

4. Royal College of Occupational Therapy. What is occupational therapy? 2019 https://www.rcot.co.uk/about-occupational-therapy/what-is-occupational-therapy

5. Greer L, McCabe S, O'Reilly C. Evaluation of a model of Occupational Therapy in primary care: A lot to offer; 2020 https://nhsscotlandevents.com/sites/default/files/IF-11-1555412843.pdf

6. Chamberlain E, Truman J, Scallan S, et al. Occupational therapy in primary care: exploring the role of occupational therapy from a primary care perspective. Br J Gen Pract 2019; 69(688):575-6

7. Stead J, Bownass E. Improving care, saving money: Occupational Therapy in GP practices. Br J Occup Ther. 2017; (80):16-17

8. Royal College of Occupational Therapists. Living, not existing: Putting prevention at the heart of care for older people in England; 2017 https://www.rcot.co.uk/sites/default/files/ILSM-Phase-II-England-16pp.pdf

9. Brooks R, Milligan J, White A. Sustainability and Transformation Plans: occupational therapists and physiotherapists can support GPs. Br J Gen Pract. 2017; 67(664)

10. British Geriatrics Society. Fit for Frailty Part 2: Developing, commissioning and managing services for people living with frailty in community settings; 2015 https://www.bgs.org.uk/sites/default/files/content/resources/files/2018-05-23/fff2_full.pdf

11. Department of Health and Social Care. Prevention is better than cure: Our vision to help you live well for longer; 2018 https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/753688/Prevention_is_better_than_cure_5-11.pdf

12. Nikolova S, Heaven A, Hulme C, et al. Social care costs for community-dwelling older people living with frailty. Health Soc. Care Community. 2020; 00:1-8

13. Department of Health and Social Care. Care Act 2014; 2014 https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/care-act-2014-part-1-factsheets/care-act-factsheets

14. Royal College of Occupational Therapists. Occupational therapy in the prevention and management of falls in adults; 2020 https://www.rcot.co.uk/practice-resources/rcot-practice-guidelines/falls

15. Orman K. Primary care – why the push from RCOT? OT news; 2018 https://www.rcot.co.uk/file/3117/download?token=vW3P2EaA

16. Campaign to End Loneliness. The facts on loneliness; 2021 https://www.campaigntoendloneliness.org/the-facts-on-loneliness/

17. Age UK. All the Lonely People: Loneliness in later life; 2018 https://www.ageuk.org.uk/globalassets/age-uk/documents/reports-and-publications/reports-and-briefings/loneliness/loneliness-report.pdf

18. Seale C, Anderson E, Kinnersley P. Comparison of GP and nurse practitioner consultations: an observational study, Br J Gen Pract. 2005; 55(521):938-43

19. Stinson M, Gillan C, Porter-Armstrong A. A Literature Review of Pressure Ulcer Prevention: Weight Shift Activity, Cost of Pressure Care and Role of the Occupational Therapist. Br J Occup Ther. 2013 76(4):169-78

20. Macens K, Rose A, Mackenzie L. Pressure care practice and occupational therapy: findings of an exploratory study. Aust Occup Ther J 2011;58(5):346-54

Related articles

View all Articles