Identifying adverse drug reactions

Ross Ferguson

Ross Ferguson

Author, Pharmacy management of long term medical conditions.

Pharmaceutical Press; 2021

Practice Nurse 2021;51(9):22-27

With more and more patients taking increasing numbers of prescription drugs, preventing, identifying, managing, and learning from, adverse drug reactions are essential to ensure that people get the best out of their medicines

Aside from staff, the highest cost in the NHS is the bill for medicines. Coming in at a list price of £20.9 billion in 2019-20 (the most recent full year for which figures are available) this is an increase of 9.9% from the previous year.

While around 55% of this expenditure is accounted for by hospitals, the remainder (£9 billion) can be attributed to primary care and this is rising at 5% per annum.1

Aside from the significant fiscal implications, one needs to consider the impact on individuals, as rising drugs costs alone do not account for these huge figures.

The number of people taking medicines is increasing as a consequence of the ageing population and it is known that older people take more medicines. In fact, in a recent Public Health England survey,2 43% of men and 50% of women reported that they had taken at least one prescribed medicine in the last week and 22% of men and 24% of women reported that they had taken at least three prescribed medicines in the last week.

This proportion increased with age, with more than half of participants aged 65-74 and more than 70% of those aged 75 and over having taken at least three prescribed medicines.

Age UK estimates that almost two million people over 65 are likely to be taking at least seven prescribed medicines, and that this number doubles to nearly four million for those taking at least five medicines.3

Moreover, multimorbidity, defined as having two or more long-term medical conditions, is almost universal in adults and prevalence increases with age. The prevalence of multimorbidity in England is around 27%, with 33% of these people having both a physical and mental morbidity.4 And it is known that 50% of people taking medicines for long-term medical conditions do not take them as intended.5

As well as the health benefits gained from ready access to medicines there are also the possible harms to consider in all these people, as a meta-analysis which assessed the percentage of people with preventable adverse drug reactions among outpatients and people admitted to hospital, found that approximately half were preventable.6

Preventing, identifying, managing and learning from adverse drug reactions are essential elements in ensuring that people get the best out of their medicines.

WHAT IS AN ADVERSE DRUG REACTION?

An adverse drug reaction (ADR) can be defined as:7

- An unwanted or harmful reaction which occurs after administration of a drug or drugs and is suspected or known to be due to the drug(s).

- A response to a drug that is noxious, unintended, and occurs at doses normally used for prophylaxis, diagnosis, or treatment of disease, or for modification of physiological function

ADRs can be categorized as Type A or Type B.

Type A reactions (pharmacological/ augmented reactions) are more common and account for more than 80% of all reactions. They result from an exaggeration of a drug’s normal pharmacological actions when given at the usual therapeutic dose (e.g. bleeding with warfarin). They are dose dependent and so the reaction is reversible when the dose is reduced, or treatment stopped. This type also includes reactions that are not directly related to the desired pharmacological action (e.g. dry mouth with tricyclic antidepressants).

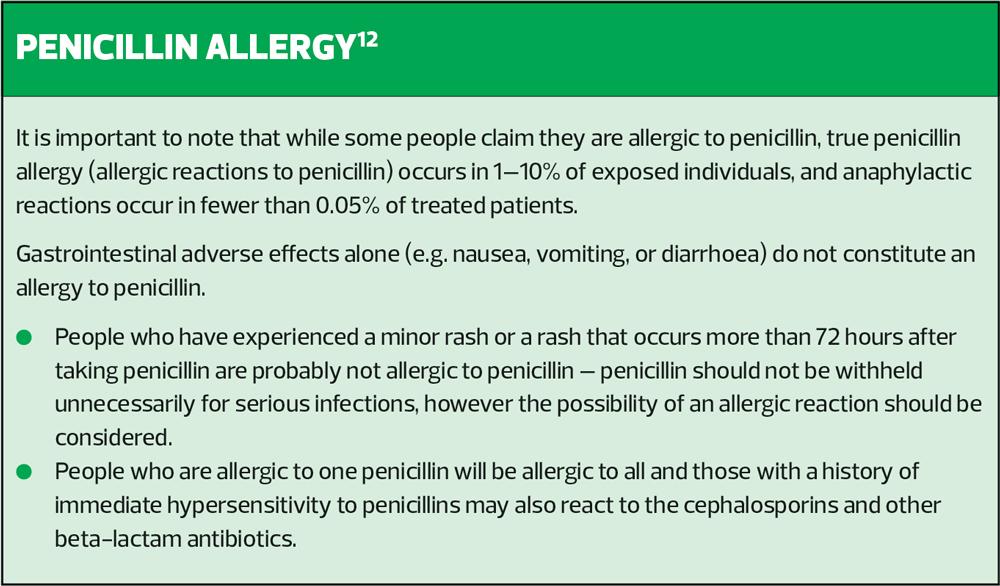

Type B reactions (idiosyncratic/bizarre reactions) cannot be predicted from the known pharmacology of the drug (e.g. anaphylaxis with penicillin and skin rashes with antibiotics).

Type B reactions may only be discovered for the first time after a drug has already been made available for general use.

Other categories of ADRs include:

- Type C reactions – continuing reactions

- Type D reactions – delayed reactions

- Type E reactions – end-of-use reactions.

According to the Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency (MHRA), ADRs adversely affect patients’ quality of life and can also cause patients to lose confidence in the healthcare system. In addition, they contribute to increased costs of patient care and can lengthen hospital stays and may mimic disease, resulting in unnecessary investigations and delays in treatment.

INCIDENCE OF ADRs

The exact incidence of ADRs is unknown, but a recent study showed that ADRs accounted for approximately 3.5% of hospital admissions and another study identified that ADRs were the cause of around 197,000 deaths in Europe annually.8

The causes of ADRs are multifactorial and complex, but risk factors associated with development of ADRs include (but are not limited to):9

- Age

- Elderly – multiple medical problems, multiple medicines, reduced capacity for metabolising drugs

- Infants and very young children – immature physiological functions

- Gender – women tend to have lower body weight and organ size, more body fat, different gastric motility and lower glomerular filtration rate, affecting pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics

- Maternity status – physiological changes that occur during pregnancy can affect drug pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics

- Kidney function – reduced renal function can lead to toxicity, or reduced therapeutic effect

- Body weight – this can affect distribution of the drug in the body and consequently exposure to it

- Race and ethnicity – genetic factors affect drug metabolism and the body’s response to drugs

- Smoking – this can affect liver enzymes and the metabolism of some drugs.

- Polypharmacy – the number and severity of ADRs increases disproportionately as the number of drugs taken increases.

- Disease factors – multiple diseases make people more vulnerable to ADRs. The disease can affect the response to drugs (e.g. kidney disease), and the drugs may worsen some conditions (e.g. NSAIDs in people with peptic ulcers).

DRUG MONITORING AND SAFETY

The MHRA and the Commission on Human Medicines are the UK bodies responsible for monitoring the safety of all medicines in the UK. The Commission on Human Medicines (CHM) is an advisory non-departmental public body sponsored by the Department of Health and Social Care, which advises ministers on the safety, efficacy and quality of medicinal products.

The MHRA is an executive agency of the Department of Health and Social Care. Among other things, it is responsible for:10

- Ensuring that medicines, medical devices and blood components for transfusion meet applicable standards of safety, quality and efficacy

- Ensuring that the supply chain for medicines, medical devices and blood components is safe and secure.

The pharmacovigilance process involves:

- Monitoring the use of medicines in everyday practice to identify previously unrecognised adverse effects or changes in the patterns of adverse effects

- Assessing the risks and benefits of medicines to determine what action, if any, is necessary or needed to improve their safe use

- Providing information to healthcare professionals and patients to optimise safe and effective use of medicines

- Monitoring the effect of any action taken.

The development of the current pharmacovigilance system resulted from the thalidomide disaster (1956-1961) which led to a focus on regulation, the introduction of the Medicines Act 1968, and the setting up of the Committee on Safety of Drugs (CSD). The CSD later became the Committee on Safety of medicines (CSM), and was replaced by the Commission on Human Medicines (CHM) in 2005.

The MHRA was formed in 2003 with the merger of the Medicines Control Agency and the Medical Devices Agency.

In 1964 the Yellow Card Scheme was introduced (https://yellowcard.mhra.gov.uk/) allowing doctors to report suspected adverse drug reactions. The Scheme has now been developed to allow reporting by any healthcare professionals as well as members of the public.

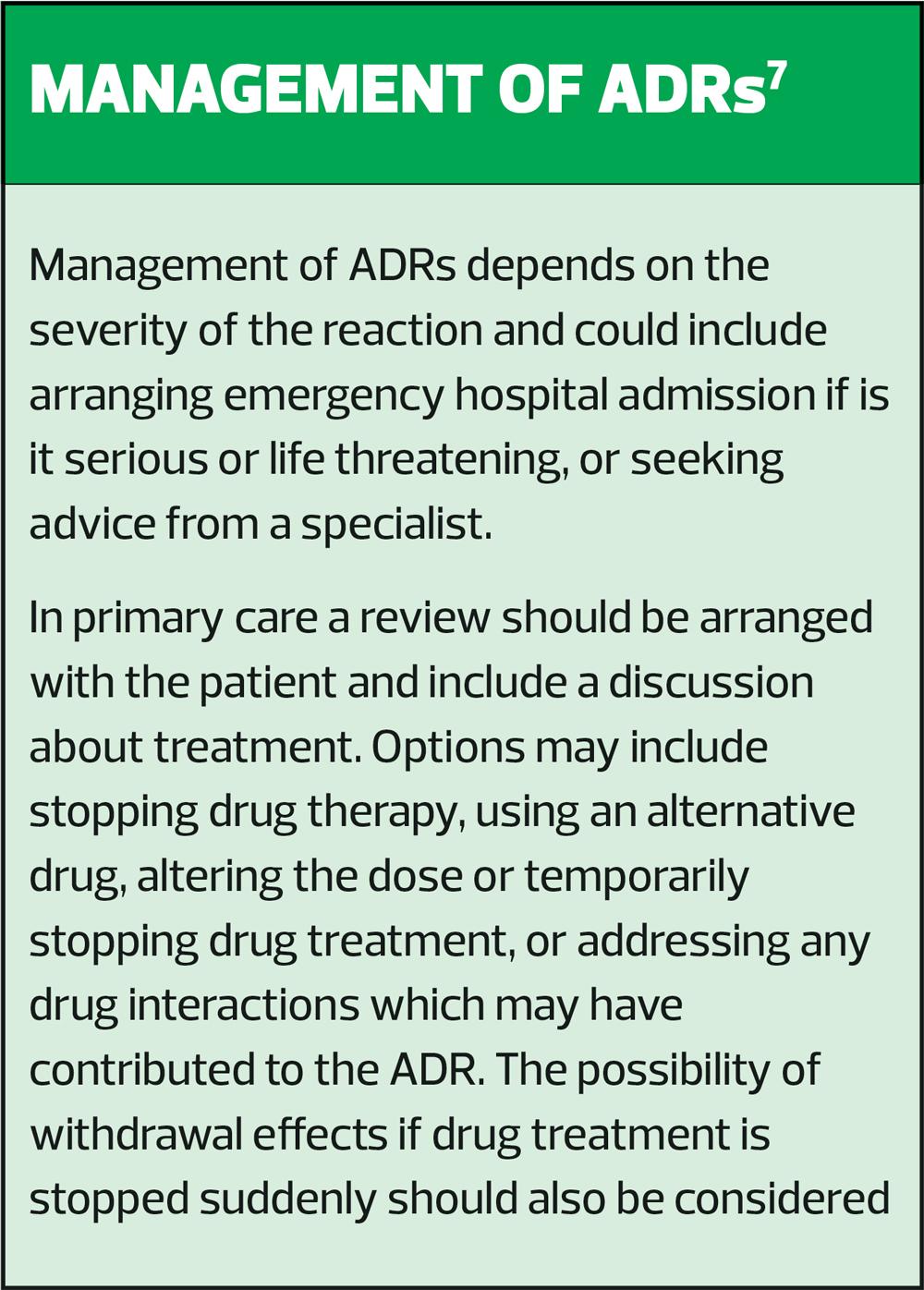

REPORTING RESPONSIBILITIES7

All suspected ADRs that are serious, medically significant, or result in harm, should be reported. This includes reactions that are fatal, life-threatening, disabling or incapacitating, or result in or prolong hospitalisation, or where there is a congenital abnormality. For established medicines and vaccines all serious suspected ADRs should also be reported even if the effect is well recognised.

In addition, any ADRs, whether they are considered serious or not, should be reported for ‘Black Triangle’ products. These are new drugs and vaccines that are being intensively monitored by the MHRA to confirm their risk/benefit profile. These products can be identified by an inverted black triangle in the British National Formulary (BNF) as well as other drug reference sources. Products usually retain a Black Triangle status for 5 years, but this can be extended if necessary.

The list of Black Triangle products is updated monthly and can found on the European Medicines Agency (EMA) website.

COMMON ADVERSE EFFECTS AND IMPLICATED DRUGS

In one systematic review of ADRs,8 the most commonly reported ADRS were those associated with the central nervous system, gastrointestinal system and cardiovascular system. The classes of drugs associated with the highest ADRs were drugs used for the cardiovascular system (e.g. beta blockers, diuretics, ACE inhibitors) warfarin, antipsychotics and opioid analgesics.

In another review,11 the most frequent drug classes involved in the ADRs among adults were cardiovascular drugs including antihypertensive, lipid-modifying, antithrombotic drugs; followed by nervous system drugs including antidepressants, antipsychotics, analgesics; and musculoskeletal system drugs, including NSAIDs, antirheumatic drugs, and drugs for bone structures and mineralisation (e.g. bisphosphonates).

It is important therefore to be vigilant in people taking these classes of medicines, particularly if they have additional risk factors.

DIAGNOSIS AND ASSESSMENT

Identifying possible ADRs involves listening to patients’ concerns about their medicines and any problems they are experiencing, as well as your own observations, as not all ADRs may be obvious to the patient. The MHRA advises that other things to be alert for include:13

- Abnormal clinical measurements (e.g. temperature, pulse, blood pressure, blood glucose, body weight) while on drug therapy

- Abnormal biochemical or haematological laboratory results while on drug therapy.

- If new drug therapy is started which may be used to treat the symptoms of an ADR.

- Considering the opinion of a parent if concerning a child.

A history should include:

- When it started – the time from when use of the drug was started to when the reaction develops may be characteristic of the reaction, and if the drug was stopped, the time it took for the reaction to abate as this is related to the duration of action of the drug.

- Remember, some drugs have a very long duration of action and so the ADR may occur some time after it has been stopped.

- Relationship to dose – ADRs are often dose related and may be minimised by reducing the dose of the drug.

- If symptoms resolve when the drug is withdrawn, and if symptoms recur if the drug was reintroduced. However, deliberate re-challenge is only very rarely justified (clinically and ethically) after serious ADRs, because of the risks involved.

- Other possible causes – underlying illness or another disease, other medications (including self-medication and herbal remedies), drug interactions.

- Drug history – take a complete drug history, including history of allergy or previous ADRs.

Once you have the relevant information, the adverse effect profile of the drug should be checked to consider whether the signs and symptoms have been reported before. The BNF and the manufacturer’s Summary of Product Characteristics (SPC) in the electronic Medicines Compendium (www.medicines.org.uk) are useful resources. It should be noted that there may be differences between the ADRs listed in the SPC compared to the BNF, this is because the BNF may omit them if a causal link has not been established.

A complete listing of suspected ADRs for individual drugs that have been reported to the MHRA through the Yellow Card scheme by health care professionals, members of the public, and pharmaceutical companies can be found at Interactive Drug Analysis Profiles (iDAPs) – https://yellowcard.mhra.gov.uk/idap.

In some cases additional examinations and investigations may be necessary to confirm that that and ADR has occurred.

Case study

Satbinder, aged 48 years, has phoned the practice and has asked to speak to you. He recently started a course of antibiotics and explains that he is allergic to them and he’s not sure what to do. (Ed. Answers can be found in the box to the right of the article - no cheating!)

Q1. What is the most appropriate response?

a) Advise Satbinder to stop taking the antibiotic

b) Advise him to finish the course

c) Take a full history

You take a medical history and Satbinder tells you he is on day 3 of a 5-day course of amoxicillin 500 mg for acute bronchitis. He is also taking the following medicines:

- Ramipril 5 mg daily

- Metformin 500 mg 2 g daily (in divided doses)

He feels sick and you ask about any other symptoms or issues he is experiencing. He tells you he has an annoying cough, which he attributes to the infection. The sickness started today, but he’s had the cough for over a week.

Q2. At this stage do you suspect he is suffering from an ADR?

a) Yes

b) No

c) More information is needed

You ask Satbinder whether he’s taken amoxicillin before and enquire how long he has been taking his other medicines. He isn’t sure if he’s had amoxicillin before, but you can see from his records that he has had phenoxymethylpenicillin before and there was no reported ADR.

He advises you that he recently had a medication review and had his metformin dose increased and he was also started on ramipril as he has developed high blood pressure.

The cough is keeping him awake at night (as well as his partner) and the nausea is putting him off his food.

Q3. In view of this additional information, what is the most appropriate action?

a) Advise Satbinder to stop all medicines to see if the symptoms stop

b) Tell Satbinder to continue taking the medicines and phone back if they continue after he finishes the course of amoxicillin

c) Ask Satbinder to come down to the practice to discuss the issues further

You advise Satbinder to continue with the antibiotic, but to come to the practice for a more detailed discussion and to have his medication reviewed as it is possible that the cough is caused by the ACE inhibitor and nausea by the increase in the dose of metformin.

Notes

- Gastrointestinal adverse effects alone do not constitute a penicillin allergy.

- Cough occurs in about 15% of people taking an ACE inhibitor and it can occur at any time after starting treatment — if the cough is troublesome and other causes have been ruled out, switching to an angiotensin-II receptor blocker should be considered.

- Nausea is a common adverse effect of metformin, but usually resolves spontaneously in most cases.

REFERENCES

1. NHS Digital. Prescribing Costs in Hospitals and the Community 2019-2020; 2020. https://digital.nhs.uk/data-and-information/publications/statistical/prescribing-costs-in-hospitals-and-the-community/2019-2020

2. NHS Digital. Health Survey for England – 2013; 2014 https://digital.nhs.uk/data-and-information/publications/statistical/health-survey-for-england/health-survey-for-england-2013

3. Age UK. Age UK calls for a more considered approach to prescribing medicines for older people; 2019 .

4. Cassell A, Edwards D, Harshfield A, et al. The epidemiology of multimorbidity in primary care: a retrospective cohort study. Br J Gen Pract 2018; 68 (669): e245-e251. doi.org/10.3399/bjgp18X695465

5. Sabaté E, ed. Adherence to Long-Term Therapies: Evidence for Action. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2003.

6. Hakkarainen KM, Hedna K, Petzold M, Hägg S. Percentage of patients with preventable adverse drug reactions and preventability of adverse drug reactions – a meta-analysis. PloS ONE 2012; 7(3): e33236. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0033236

7. NICE Clinical Knowledge Summaries. Adverse drug reactions; 2017 https://cks.nice.org.uk/topics/adverse-drug-reactions/

8. Khali H, Huang C. Adverse drug reactions in primary care: a scoping review. BMC Health Services Research 2020; 20(1):5. doi: 10.1186/s12913-019-4651-7.

9. Alomar MJ. Factors affecting the development of adverse drug reactions. Saudi Pharmaceutical Journal 2014; 22(2):83-94. doi: 10.1016/j.jsps.2013.02.003.

10. Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA). About us. https://www.gov.uk/government/organisations/medicines-and-healthcare-products-regulatory-agency/about

11. Insani WN, Whittlesea C, Alwafi H, et al. Prevalence of adverse drug reactions in the primary care setting: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One 2021; 16(5):e0252161. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0252161. eCollection 2021.

12 Joint Formulary Committee. British National Formulary London: BMJ Group and Pharmaceutical Press. https://www.medicinescomplete.com.

13. MHRA. Guidance on adverse drug reactions. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/949130/Guidance_on_adverse_drug_reactions.pdf

Related articles

View all Articles