Helping your patients master their pain

Dr Nicola Sherlock

Dr Nicola Sherlock

D Clin Psych, C Psychol.

Consultant Clinical Psychologist,

Southern Health & Social Care Trust, NI

Practice Nurse 2021;51(9):22-25

Psychosocial factors play a key role in the experience of chronic pain and there are practical strategies that can be helpful in chronic pain management

When we consider the psychosocial factors that play a role in chronic pain, it is helpful to first reflect on the differences between acute and chronic pain. Acute pain typically has a specific cause, for example, it may arise from tissue damage, inflammation or a disease process. Acute pain usually lasts for a specific time period, from seconds up to around three months until whatever is causing the pain is healed or resolved. Importantly, acute pain serves a useful biological function. It is typically a cue for the body to do something to stop the pain, for example, to rest after an ankle sprain. In contrast, chronic pain, also known as persistent pain, is pain that lasts for more than about three months or beyond expected healing time. It is more complex and difficult to understand and typically, it serves no useful purpose.

Chronic pain is a huge problem with a significant physical, emotional and economic burden. It is believed that between one-third and one-half of the population in the UK live with chronic pain. The vast majority of patients have their pain managed in primary care, with only a small minority of patients attending specialist pain clinics.

In April 2021 NICE published new chronic pain guidelines for the assessment of chronic primary and secondary pain and the management of chronic primary pain in over 16s.1 This states that chronic pain can be secondary to an underlying condition, for example, osteoarthritis or rheumatoid arthritis. Pain can also be classified as chronic primary pain. Chronic primary pain has no clear underlying condition or the pain, or the impact of the pain is out of proportion to any observable injury or disease. Examples of chronic primary pain include fibromyalgia, (chronic widespread pain), complex regional pain syndrome and chronic primary musculoskeletal pain. Chronic primary and secondary pain can co-exist and it is important to note that all forms of chronic pain can cause distress and disability.

THE BIOPSYCHOSOCIAL MODEL OF PAIN

The International Association for the Study of Pain (ISAP) notes that pain is always a personal experience and that we should use a biopsychosocial framework when we consider the assessment and management of chronic pain. According to the biopsychosocial model, the experience of pain is influenced by psychological and social factors as well as biological factors.2 Key psychological factors that influence pain experience are anxiety, depression, previous trauma and expectations and beliefs about their condition. Significant social factors that influence pain include social deprivation and a lack of social support.

When we are assessing a patient presenting with chronic pain, we need to establish a collaborative and supportive relationship with the patient, irrespective of whether they are presenting with chronic primary pain, chronic secondary pain or both types of pain. It is crucial that the patient feels understood and believed and thinks that their pain, and any associated distress, is being taken seriously. A good assessment will include information about how the patient's pain affects their work, their day to day activities and their sleep. Stressful life events can make pain more difficult to manage so they are worth asking about. It is important to enquire about the patient's psychological well-being while being sensitive to the fact that the patient may be concerned that you think that their pain is ‘not real’ if they are also presenting with psychological difficulties like depression and anxiety. An individual’s socioeconomic circumstances can influence their pain, for example, poor housing or financial concerns can impact the experience of pain.

When carrying out a pain assessment we should also pay attention to the pain management skills that the patient has already developed. We could ask them about the things that help them manage when their pain is difficult to control.

When we have a carried out our assessment with the patient we can begin to formulate an understanding of the psychosocial factors that may be contributing to their pain experience. I am now going to outline some key considerations that would be helpful when providing support to a person who is living with pain and some possible ways to move forward with them.

PAIN EDUCATION

Making sense of pain is a natural human response. Patients who subscribe to a purely biomedical model of pain may become very frustrated at the absence of a definitive diagnosis or treatment plan. They may find it difficult to understand why their painkillers do not ‘kill’ their pain. It is important to enquire about the patient’s understanding of their condition. What would they like to know about it, what are they most afraid of? Do you need to educate them about the nature of chronic pain and provide them with an opportunity to find out more about their condition? Have they any particular worries about their condition, for example, do they have concerns that their pain will become so bad that they will be unable to work or that they will end up in a wheelchair? Do they worry that their pain is a symptom of something sinister, for example, do they think that they have cancer? These questions can help us understand the beliefs that the patient has about their condition and the management of it.

There is evidence that information and education about the nature of chronic pain and pain conditions can help with pain management.3 As recommended in the NICE guidelines, information should be provided to the patient, and their family members and carers as appropriate, at all stages of their care, to help them make decisions about their condition, and to assist them with self-management.

Some people who live with pain catastrophise about their condition. Catastrophising is often related to the misinterpretation of illness information. Education about a patient’s condition can help challenge specific catastrophic pain beliefs. Good quality written information can be very helpful for people living with pain and their families. Many organisations have produced information leaflets that can be beneficial for patients to read, for example, Versus Arthritis provides excellent leaflets on a range of common chronic pain conditions.

The person living with pain should be informed that it is likely that their symptoms will fluctuate over time and they may experience flare-ups in their pain. A reason for the flare-up of pain may not be identified. The person living with pain should be informed that their pain may need ongoing management but that there can be improvements in quality of life even if the pain remains unchanged.

When reporting normal or negative test results to the patient, it is important to be careful about how this information is communicated and it is necessary to be sensitive to the risk of invalidating the person’s experience of their pain. It is important to appreciate that often there is no significant correlation between the amount of pain reported and the results of scans. This is illustrated by the results of a study that examined the MRI scans of individuals who had no symptoms that were indicative of cervical disease.4 The scans were interpreted as demonstrating an abnormality in 19% of asymptomatic participants, of whom 14% were less than 40 years old and 28%, older than 40. The disc was degenerated or narrowed at one level or more, in 25% of the participants under 40, and in almost 60% of those older than 40.

STRESS MANAGEMENT

Stress is a response to either a known or a perceived threat and it can be categorised as either acute or chronic stress. Stress has an important adaptive function, it can help us perform and cope in an emergency. However, we know that when stress is prolonged and chronic it can be detrimental to our health and psychological wellbeing.5

There is a reciprocal relationship between stress and chronic pain. Stress can make chronic pain worse. Stress causes muscles to tense or spasm which increases pain, and the levels of the hormone cortisol rises. This can cause inflammation and pain over time.

Chronic pain is a significant stressor. For example, people who live with the pain often report that their pain causes financial stress. They may have to take periods of sick leave from their job or they may have to give up work altogether. If they can remain at work they may have to reduce their hours or they may not be able to progress up the career ladder as quickly as they would like.

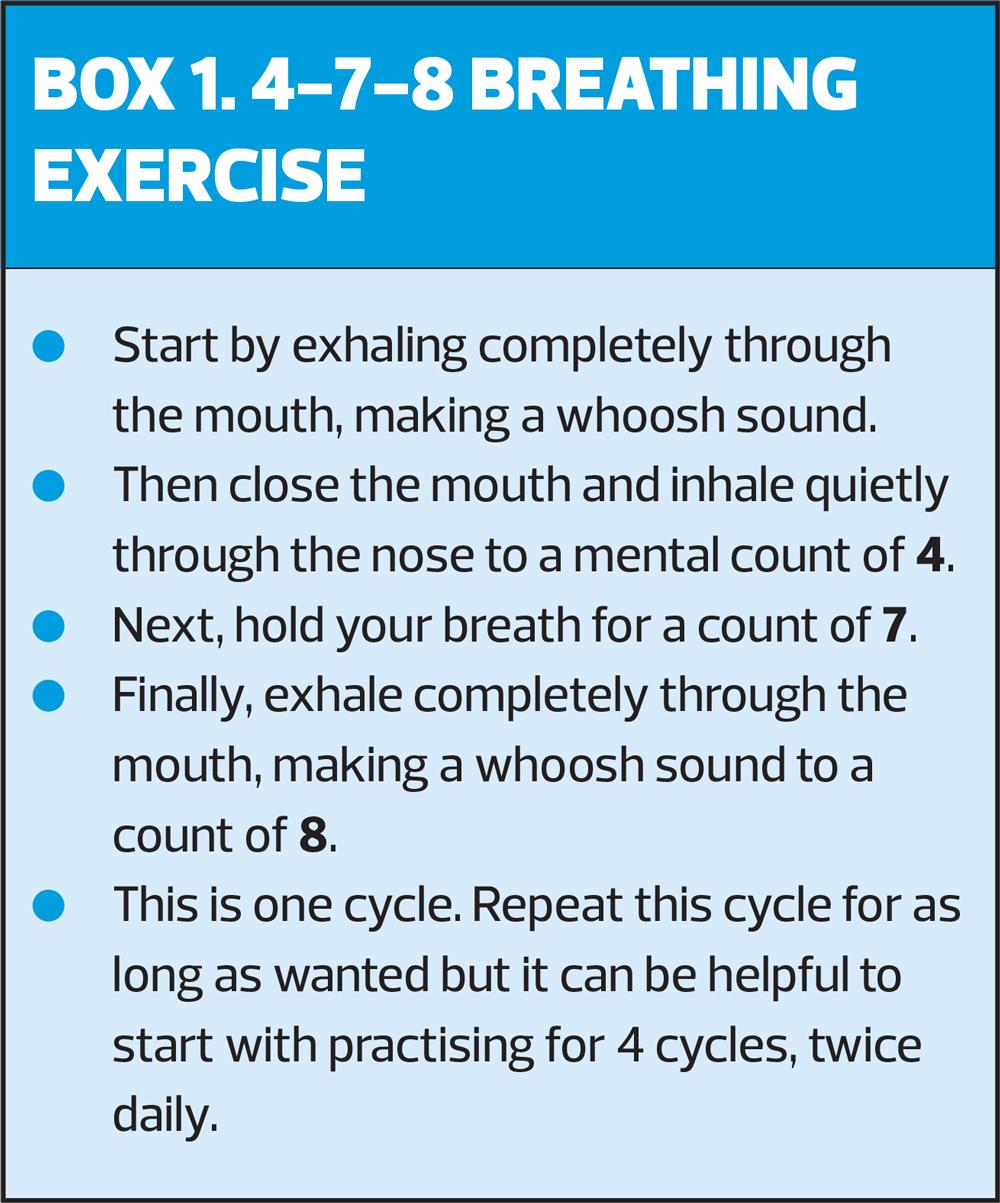

Many techniques can be helpful in the management of stress and anxiety such as breathing exercises, that are quick and easy to implement. An exercise known as 4-7-8 breathing activates the parasympathetic nervous system (PSNS). When the PSNS is activated, our body enters a state of relaxation, with our blood pressure lowering and our breathing and heart rate slowing down (Box 1).

When we encounter a stressor we often unconsciously tense our muscles. Formal relaxation exercises, like progressive muscular relaxation (PMR), can help manage stress. These exercises essentially direct the person to move their attention through the various muscle groups, tensing and relaxing their muscles. Patients could be directed online to access free guided PMR sessions – search for ‘progressive muscle relaxation exercise for pain’ on YouTube.

Making time for relaxation is an essential stress management tool. It can be helpful to encourage patients to make time to relax and engage in hobbies. Many people do not make time to do something that they enjoy regularly.

Having a designated worry time can help some people cope with stress and anxiety. To do this, the person sets aside a convenient time every day to sit down and notice their worries. Fifteen to twenty minutes a day can be set aside, during which they write down their worries. Throughout the rest of the day, when they notice that they are worrying, they can silently say ‘not now’ and come back to the worry during their designated worry time. People who use this technique often report that when they come back to their worries during their designated worry time, they find their concerns from earlier don't seem so important.

Many local areas have free stress control classes available. It can be useful to research what classes are available in your local area so that you can signpost patients to them if they identify that stress is causing difficulties in their lives.

PHYSICAL ACTIVITY

When we are working in pain management we need to consider if the patient is physically active or engaging in any physical exercise regularly. Not only is physical activity essential to our physical and psychological wellbeing, but also it is known that exercise and maintaining physical activity levels is a key component in chronic pain management. For example, the 2013 Scottish Intercollegiate Guideline Network (SIGN) guideline on the management of chronic pain states that ‘exercise and exercise therapies, regardless of their form, are recommended in the management of patients with chronic pain’.6 The NICE guidelines on the management of osteoarthritis7 state that exercise should be a core treatment for this pain condition irrespective of age, comorbidity, pain severity and disability. The guidelines note that exercise should include local muscle strengthening and general aerobic fitness.7

For patients living with pain there are many barriers to becoming more active. The most significant barrier is likely to be a fear of making the pain worse through exercise, which is known in the literature as ‘fear avoidance’.8 According to this model, it is common for people who live with pain to become fearful that activity will lead to more harm and pain. As a result, they seek to avoid exacerbations of pain by avoiding activity, and this leads to general disuse and deconditioning which results in further disability. Many studies have shown that fear-avoidance or activity anxiety is a key psychosocial risk factor in chronic pain. For example, research has shown that patients with low back pain who avoid physical activity suffer greater disability and distress whereas those with less avoidance have better emotional and physical functioning.9

When we are discussing physical activity and exercise with patients it is important to ask them about the barriers to becoming more active, while being mindful that many of them will be anxious about making their pain worse. To help them manage this anxiety, it is necessary to help them set realistic and achievable goals about their activity levels. Many times, people who live with pain set themselves unrealistic activity goals that are based on how active they were before they developed their pain, and quickly become frustrated when they cannot achieve them.

Physiotherapists are experts in helping people who live with pain become more active. They can develop programmes for people to help them overcome activity anxiety and can address their fears. If your patient appears very inactive or seems fearful of increasing activity levels it is worth considering a referral to physiotherapy services for specialist support.

PACING

It is common for people who live with pain to have difficulties pacing their activity. They may become underactive or they make engage in episodes of overactivity leading to a ‘boom bust’ cycle.

When living with chronic pain, it is easy to fall into the trap of consistently reducing activity levels in an attempt to gain short-term relief from pain. Over time, physical activity becomes more challenging as they become deconditioned and lacking in stamina.

When engaging in a ‘boom bust’ cycle the person living with pain will have periods of overactivity followed by periods of underactivity as they try to cope with increased levels of pain and fatigue.

Typically, this period of overactivity is driven by feelings of frustration about the impact that their pain is having on their life. On a good day, they try and get as much done as possible, attempting to push through the pain. Often, they experience a period of increased pain and fatigue as a result and are forced to reduce their activity levels. When their symptoms ease they again engage in a period of overactivity, and so the cycle continues.

Pacing of activity can be a helpful pain management tool. Pacing involves managing activity and energy levels to minimise pain while maximising productivity. Pacing techniques aim to minimise flare-ups of pain by taking regular short breaks in activity before pain becomes more intense and by alternating between tasks and activities. When pacing effectively, activities are spread more evenly across the days and weeks and ultimately, over time, overall levels of activity increase.

Pacing of activity is often challenging for patients as their baseline for activity may be very low. It can be difficult for people with pain to stop or take a break from an activity when they were used to being much more active before they developed their pain. Some reassurance about the benefits of pacing can help people cope with these challenges.

Planning activities is also helpful in preventing the escalation in pain that is common with boom-bust activity cycles. I often suggest that people spend a few minutes a week, perhaps on a Sunday evening, planning their week. A diary allows for scheduling of activities; activities that are pleasurable and less pleasurable. It will allow the patient to see if there are days in the week where they have many activities planned and days in the week where they have little. They may decide to balance out their schedule by being a little more active on their ‘quiet day’.

DEPRESSION

Chronic pain and depression frequently co-occur.10 When someone who is living with pain is also depressed they are more likely to have a poor treatment response and they are more likely to have decreased function.

It can be difficult to make a diagnosis of depression in a patient who is living with pain, because of the overlap between depressive symptoms and those relating to pain. Symptoms of major depression include depressed mood or diminished interest or pleasure if experienced for over 2 weeks, with additional somatic symptoms such as sleep disturbance, appetite disturbance, fatigue and cognitive symptoms such as poor concentration. Many people who live with pain also describe sleep difficulties, fatigue, cognitive difficulties, and appetite and weight disturbance.

There are several strategies that can help people manage depression. Developing a routine and making a daily plan is important. People who live with pain often find that any routine is hard to maintain. For example, if they have had a difficult night with their pain, and have slept badly, it can be hard to get up at their set time in the morning unless they need to go to work or get children on their way to school. Some people who are struggling to manage their pain report that their days are unstructured; that one day blurs into the next. This is particularly true for people who are no longer in employment. Making plans to gradually establish a daily routine and to schedule pleasurable activities can help to improve mood.

Social withdrawal is frequently reported by people who are depressed and who live with pain. When a person who is living with pain has a good social network and has social support from others, they are less likely to avoid physical and social activities. Research has found that individuals living with chronic pain who report high levels of social support experience less distress and less severe pain, with higher levels of support associated with better adjustment.11 Signposting patients to local support and community organisations can help increase a patient’s social network if they are socially isolated or lacking in practical or emotional support.

When your patient is depressed it is important to consider whether their depression is being adequately managed? If they are on anti-depressant medication does the medication need to be reviewed? Would they benefit from referral to local counselling/psychotherapeutic services?

SLEEP

The inability to sleep well is a common difficulty for people who live with chronic pain. Research indicates that having a bad night’s sleep can make you more sensitive to pain.12

There are many techniques that can significantly improve sleep if they are consistently employed. Setting a sleep schedule and developing a sleep routine is crucially important.

A sleep schedule essentially means that you go to bed at roughly the same time every night and get up at the same time every morning, including weekends. It is recommended that people do not stay in bed tossing and turning if they cannot sleep. If they cannot sleep after about 20-25 minutes, it is advised to leave the bedroom and go to another room. They should sit in dim lighting, doing something restful like reading or listening to some music. It is best if they don’t eat. When they feel sleepy, they can return to bed.

In the time before bed, a sleep routine will serve as a prompt to the subconscious mind – signalling that it is time for bed. Some people find that a warm bath or shower is a relaxing part of their bedtime routine too. It is helpful as it increases the body surface temperature initially, followed by cooling; our core body temperature falls as we drop off to sleep.

Electronics should not be used in the bedroom. This advice can be difficult to implement for people, simply because we are all so attached to our TVs, phones, tablets and laptops. We know that electronic devices – like smartphones and tablets – emit blue light, which has the same wavelength of light as the morning sun. This reduces the amount of melatonin produced, thus impacting sleep. Ideally, people would not watch TV or use their smartphone or tablet for about 90 minutes before bed. If limiting the use of your smartphone or tablet before bed is too difficult, they could consider downloading an app on their phone that limits the amount of blue light emitted from their screen. They might also consider buying amber glasses which cut out blue light wavelengths.

When a patient reports sleeping difficulties, it is worth enquiring about their caffeine intake. Caffeine has a long half-life, approximately 6-7 hours, depending on a person’s genetic make-up. Even if someone reports that caffeine does not affect their ability to fall asleep it is important to remember that caffeine also impacts the quality of sleep, reducing the capacity to experience deep sleep.

PAIN CLINICS

If your patient is very distressed and their pain is having a significant impact on multiple areas of their life, you may wish to consider referral to a specialist pain clinic. These offer psychologically-based rehabilitative treatment for chronic pain that remains unresolved by other treatment, reducing disability and distress and helping to improve your patient's quality of life.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Dr Sherlock is the author of a recently published book, Master Your Chronic Pain, which aims to help patients take control of their condition. The interventions and techniques described have consistently help to improve outcomes and reduce people's reliance on medication. Master Your Chronic Pain, published by Hawksmoor Publishing, (RRP: £15.99) is available from bookshops and online booksellers.

REFERENCES

1. NICE NG193. Chronic pain (primary and secondary); 2021. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng193

2. Gatchel RJ, Peng YB, Peters ML, et al. The biopsychosocial approach to chronic pain: scientific advances and future directions. Psychol Bull. 2007 Jul;133(4):581-624.

3. Mittinty M, Vanlint S, Stocks N, et al. Exploring effect of pain education on chronic pain patients’ expectation of recovery and pain intensity. Scand J Pain. 2018;18(2):211-219.

4. Boden SD, McCowin PR, Davis DO, et al. Abnormal magnetic-resonance scans of the cervical spine in asymptomatic subjects. A prospective investigation. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1990;72(8):1178-1184.

5. Schneiderman N, Ironson G, Siegel SD. Stress and health: psychological, behavioural, and biological determinants. Ann Rev Clin Psychol 2005;1:607–628.

6. Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN 136). Management of chronic pain; https://www.sign.ac.uk/media/1108/sign136_2019.pdf

7. NICE NG177. Osteoarthritis: care and management; 2014 (updated 2020). https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg177

8. Vlaeyen JWS, Linton SJ. Fear-avoidance model of chronic musculoskeletal pain: 12 years on. Pain 2012;153(6):1144-1147.

9. McCracken LM, Samuel VM. The role of avoidance, pacing, and other activity patterns in chronic pain. Pain 2007;130(1-2):119-25.

10. Bair MJ, Robinson RL, Katon W, Kroenke K. Depression and pain comorbidity: a literature review. Arch Intern Med 2003;163:2433–45.

11. Lopez-Martinez AE, Esteve-Zarazaga R, Ramirez-Maestre C. Perceived social support and coping responses are independent variables explaining pain adjustment among chronic pain patients. J Pain 2008;9:373–9.

12. Sivertsen B, Lallukka T, Petrie KJ, et al. Sleep and pain sensitivity in adults. Pain 2015;156(8): 1433–1439.

Related articles

View all Articles