Drug interactions with Complementary and Alternative Medicine

DR ED WARREN

DR ED WARREN

FRCGP, FAcadMEd

As reported in Practice Nurse last month, prescribers have been reminded to routinely ask people about their use of herbal medicines and supplements that could interact with prescription medicines after a new study highlighted the frequency of concurrent use. We explore the issue in more detail

It should not be a surprise that our patients are keen on complementary and alternative medicine (CAM). What would now be considered mainstream medicine only really got up a head of steam during the 20th century. Much CAM would have been considered mainstream before the rise of scientific medicine, as there was little else available to treat the ailments of the day.

With such a back-story, the statistics on CAM paint a relatively modest picture of use. Official figures are a little hard to come by, but in 2008 it was estimated that the annual UK spend on CAM was £4.5 billion.1 That is a lot of money, but only a fraction of the nation’s total spend on healthcare – the NHS budget for that year was just shy of £100 billion.2 The majority of CAM in the UK can only be obtained on a private basis, but some is accessed on the NHS. Individual NHS practitioners can, at their discretion, offer their patients CAM. Around 400 GPs are members of the British Homeopathic Association.3

Belief in the effectiveness of CAM remains strong. According to a YouGov survey from 2015, two thirds or more of people believe that chiropractic, osteopathy and acupuncture are effective.4 These three are widely available through the NHS, and there is some evidence for their effectiveness – for example acupuncture is offered in a majority of NHS pain clinics,5 apparently on a ‘try it and see, if all else fails, at least it is unlikely to do any harm’ basis. Just over 50% in this sample believed herbal medicines to be effective. For reflexology the figure was 49%, for traditional Chinese medicine 40%, and for homeopathy (i.e. doing absolutely nothing6) 39%. Of some concern is that 3% of people thought that astrology was a good way of treating disease.

WHO USES CAM?

The Health Survey for England in 2005 included questions about CAM use.7 Data were available from 7,630 respondents, with an impressive family response rate of 71%. Of these 44% had used CAM at some time in their lives, and just over a quarter (26%) had used CAM in the previous 12 months, so might be considered to be current users.

Groups most likely to use CAM were:

- Women

- University educated

- Suffering from anxiety or depression

- Poorer mental health – as assessed on General Health Questionnaire

- Lower perceived social support

- Eating five or more portions of fruit and vegetables a day

From the same survey, looking at just the people taking prescription drugs, 29% had used CAM in the previous 12 months.7 It is plausible (but not proven) that those who used a CAM such as aromatherapy or acupuncture were unlikely to have their prescribed medication interfered with by their CAM. However, such an assumption of safe co-usage is much less likely to apply with patients who take herbal or traditional Chinese medicines.

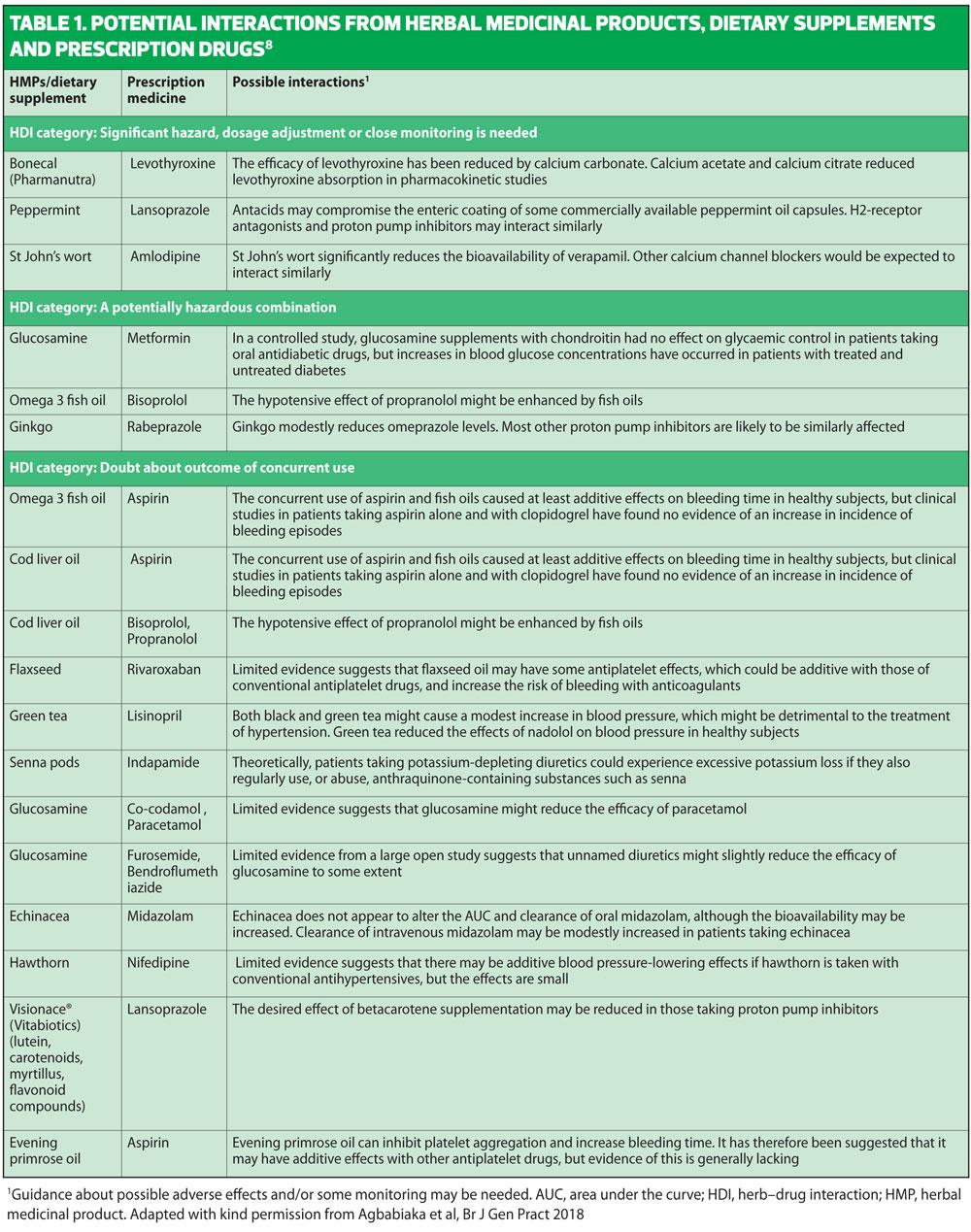

DRUG INTERACTIONS WITH CAM

A recently published study8 using two populations aged over 65 years from general practices in the south of England found that around a third of patients taking prescription drugs were also taking herbal remedies and/or food supplements (an average of three each). They were also taking an average of three prescription drugs each. Using Stockley’s, a reputable textbook as a source,9 they then went through each patient survey response to find out whether any drug/herbal interaction was likely, and if so how serious it was likely to be. In just over half of subjects no potential interaction was found between prescription drugs and herbal remedies and/or food supplements, but in just under half there was. Of the 21 patients with possible interactions, in three cases the interaction was deemed ‘potentially hazardous’ and in three ‘significantly hazardous’. No doubt none of the survey subjects had given any thought to possible interactions, and the information supplied with the herbal remedy and/or food supplement was either left unread, or was insufficient or confusing. Such criticism could also be levelled at the pack inserts that appear with prescription drugs.

This is a small study, but the findings are plausible given what is already known about prescription drug use and herbal medicines use in this age group.

No particular herbal remedy was implicated in causing troublesome drug interactions. In this study 14 different herbal remedies were identified as causing possible problems. The commonest method of interaction was that the herbal remedy altered the absorption of the prescribed drug, or altered its bioavailability in some other way. This means that the dosage of the prescribed drug is rendered either too much or too little. However this was far from being the only mechanism implicated.

Some of the herbal remedies highlighted as causing problems by this study are very well known and widely available.

- St John’s wort is used for the symptoms of depression. Depression is very common: 5% of adults have an episode of depression each year, and 10% of men and 25% of women have a depression needing treatment at some time in their life.10 St John’s wort is not a treatment recommended by NICE, in part because it interacts with several prescription drugs,11 but that does not stop people buying it over the counter. It poses a significant hazard when used with amlodipine, commonly prescribed to treat hypertension and angina. St John’s wort reduces the bioavailability of calcium channel blockers (a group that includes amlodipine) by enzyme induction affecting their metabolism in the gut, reducing blood levels of the drug by almost 80%.12 This runs the risk of the blood pressure and/or angina getting out of control, though there are no reports of any resultant deaths or coronary events.

- Peppermint oil has antispasmodic qualities and is widely taken (and also prescribed when made up into capsules ) for irritable bowel syndrome (IBS). Up to 20% of people have IBS, a figure that actually decreases with age.13 Two recent large systematic reviews have shown that peppermint oil is effective in IBS, and a trial of use is endorsed by NICE.14 Proton pump inhibitors (PPIs), such as omeprazole and lansoprozole are prescribed for (amongst other things) peptic ulcer disease and acid reflux. Since the differential diagnosis of dyspeptic symptoms is considerable,15 it is quite likely that a PPI and peppermint oil might be used in the same patient. Unfortunately PPIs are very powerful and reduce acidity so much that this can disrupt the peppermint oil capsule so that the oil is released into the stomach (and not further down the GI tract as intended) causing more dyspepsia. This is a theoretical risk, and is not supported by research evidence, but is sufficiently concerning that the makers of some peppermint oil capsule preparations include the interaction in the leaflet insert.16

- In the study mentioned above,8 three of the 21 interactions identified were with glucosamine. Glucosamine is made in the body, and is found at higher concentrations in cartilage, tendons and ligaments. Oral supplements are supposed to help with osteoarthritis and other rheumatic pains. A Cochrane systematic review in 2014 suggested that any benefit from glucosamine in osteoarthritis is unreliable and NICE does not recommend its use.17 However, evidence rarely gets in the way of selling a health supplement. The literature contains one report of glucosamine raising serum glucose levels in a diabetic, and another of glucosamine helping in a patient with repeated hypoglycaemic episodes. It is speculated that glucosamine alters glucose metabolism and also increases insulin resistance. So the evidence for an interaction between glucosamine and metformin is a little tenuous, but still sufficient to advise caution when the two are used together.18 In addition, two studies have found case reports of glucosamine reducing the effectiveness of paracetamol,19 which is unfortunate as paracetamol is one of the few analgesic drugs recommended by NICE for osteoarthritis.17

CASE STUDY – JIM

Since his diagnosis of angina, Jim had decided to take more control of his life. He was eating fewer fats and went for a brisk walk most days of the week. He also took his new medications on a religious basis, lining the tablets up each morning with his wholegrain cereal. He started to feel a lot better and more confident about his heart, but still had to use his GTN spray if he rushed upstairs too quickly.

Then a friend told him about an herbal supplement called flavenoids. It is reckoned to be good ‘if you have a dodgy ticker’, and is also an anti-oxidant which is similarly a good thing. He also heard from a friend that it was supposed to prevent cancer. Flavenoids are present in the food you eat anyway, and the supplement just gives you a little boost, so ‘what could be the harm in that’?

Commentary

One of the tablets Jim started for his angina was atorvastatin, a statin. Some flavenoids inhibit two of the enzymes that break down statins, and also increase intestinal absorption of the statin. Overall this has the effect of boosting statin blood levels. In one respect this is helpful as in CVD the lower the cholesterol the better. However, higher statin levels also run the risk of causing myopathy and rhabdomyolysis, which has a case fatality rate of 20%.20

The evidence for this interaction has been found in animal studies, notably rats, and there are as yet no instances recorded in humans,21 but there is a well recognised interaction between statins and grapefruit juice (a rich source of flavenoids) which certainly has led to myopathy and rhabdomyolysis. Stockley21 gives this interaction a grading of ‘significant hazard’.

It is particularly ironic that an herbal supplement that is supposed to be good for your heart can cause unexpected problems when combined with an ubiquitous drug used to prevent heart disease. Jim just thought he was taking care of himself.

CASE STUDY – GWEN

Gwen was in a state of anxiety nearly all the time. She had an unpleasant experience of the menopause, with hot flushes that persisted for years. She would blush deeply at the slightest provocation, and often found herself dripping in sweat, which made her reluctant to leave the house. Gwen had always believed in natural treatments where possible, and having tried several herbal remedies she eventually hit on Chinese angelica. This wasn’t perfect, but it definitely eased her hot flushes and increased her confidence. She had now been taking the remedy for 3 years.

Six months ago, Gwen found a breast lump. She went to her GP who referred her for further investigations within 2 weeks. After an agony of tests and waiting she was diagnosed with breast cancer and eventually prescribed tamoxifen. However, she was then told that taking Chinese angelica was not a good idea if you are taking tamoxifen. This posed a dilemma: Gwen remembered how troublesome her vasomotor symptoms had been and how they had interfered with her life. She also reasoned that ‘a little tablet is unlikely to make much difference to cancer’. She decided not to start the tamoxifen so that she could continue her Chinese angelica.

Commentary

Chinese angelica contains several chemicals, of which the most prevalent is a type of coumarin. It also has oestrogenic actions, which is why it helps menopausal symptoms. Tamoxifen opposes oestrogen, and helps breast cancer by blocking oestrogen to the cancer oestrogen receptors.22 This is why it is not a good idea to take tamoxifen and Chinese angelica together – the herbal treatment stops the prescribed medicine working, running the risk of the cancer growing and spreading.

Gwen’s case highlights that some patients will be more committed to their herbal treatments than they are to orthodox medicines. You may think, ‘isn’t it annoying that some irresponsible patients take stuff which might interfere with our nice prescribed drugs?’ Our patients may not see things in the same way.

REGULATING CAM

There are now more CAM practitioners in the UK than there are GPs.1 Those who are trained in other health disciplines as well as practising CAM, such as the 400 GP homeopaths, are regulated by the bodies that regulate the other aspects of their healthcare life, such as the General Medical Council (GMC) for doctors. Several universities and other academic institutions offer courses and degrees on CAM (for example the BSc course in Complementary Healthcare at Cardiff University23), and so there will be some quality control over the training process. There are also CAM associations with their own rules of conduct that apply to association members, such as the British Homeopathic Association and the Association of Reflexologists, but membership is not compulsory as it is for the GMC.

But we are looking here at CAM that may interfere with prescription medicines, so the focus must be on those that you swallow or otherwise let into your body. As a nation we spend around £120 million on these products a year.24 When a prescription medicine is introduced in the NHS, it has to undergo a rigorous programme of development, then checks, and then more checks after it comes into use. The pharmaceutical industry estimates that it costs over $2.5 billion to get a new drug onto the prescription pad.25 That figure is for each and every new drug. It is a huge sum, and some would dispute it as it includes not only development and safety insurance research costs, but also marketing costs and the cost of other drugs that never make it to market. However this is the figure that the pharmaceutical industry will use when seeking to justify the often astronomical costs of new drug treatments.

But what of CAM medicines? Traditional Herbal Registration is an attempt to regulate the quality of herbal medicines. Medicines so registered can put the THR mark on their product and marketing material. To qualify for THR, which is run by the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA – the same one that regulates prescription medicines) the product or something quite like it has to have been in use for at least 30 years (15 of which within Europe), and the clinical indication(s) for use have to be the same as it has been used for in the past. And that’s it really. Nothing about whether it works, nothing about safety, and nothing about side effects or interactions with other herbal remedies or prescribed drugs. The standard cost for registration is about £2,500,26 or about a millionth of the cost of getting a new prescription drug out.

This raises several problems:

- Some herbal remedies are not subject to any regulation at all. Medicines prepared by an herbal practitioner for an individual patient are not regulated.27

- Herbal remedies can be advertised direct to the public. In the UK prescription medicines cannot.

- Taking the herbal remedy does not automatically appear in the GP record, so that (among other things) it is not included in the prescribing software that checks for interactions.

- Drugs obtained by post or online may not be what they say they are. This is also true of prescription drugs. You can spot the dodgy websites for prescription drugs as they do not ask you for a prescription. This failsafe does not apply to herbal remedies.

- The strength of herbal teas depends on how they are brewed, which is usually done in the patient’s home. You don’t know what dose you are taking.

- Some herbal products are classified not as medicines but as foodstuffs or food supplements. They are not eligible for THR.

All the comments above remain true whether herbal remedies work or not. There are many sources of information to which you can turn to find out which CAMs work and which don’t. The most comprehensive is probably from the Cochrane Collaborative, which has an entire subgroup concentrating on just this issue.28

CONCLUSION

At any one time around a quarter of our patients are using CAM. The prevalence of chronic illness (and multimorbidity) is increasing, and so is the use of prescribed medications (and polypharmacy). The simultaneous use of prescription medicines and herbal remedies predicts a disaster waiting to happen.

Many prescribers are blissfully unaware of other things that their patients may be taking. Patients for their part often regard herbal remedies or food supplements as being irrelevant to other prescribed medications, perhaps seduced by the advertising to believe they are ‘natural’ and therefore safe. Others may feel reluctant to admit that they are trying other treatments in case the prescribing healthcare professional is offended.

Research information about prescribed drug-herbal interactions is incomplete. There are some proper trials (usually of small size), but recommendations are also made on the basis of animal studies, in-vitro work and theoretic concerns. Getting the research done is of course a responsibility for both orthodox practitioners and CAM practitioners. However, there is little incentive for the makers of herbal remedies to do much safety research as there is no regulatory requirement to do so. They may be opening a can of worms – medical research often does not give definitive clinical answers, concluding that ‘more research’ is needed, and doing research is expensive and eats into profits.

Many primary care prescribers take care to ask patients at the point of prescribing whether or not they are taking any other substances. This is often reinforced by waiting room notices, on practice websites and in leaflets. Ideally each time a patient buys an herbal remedy or food supplement this would automatically be entered into their GP patient record so that the prescribing software can take account of it and flag up any potential problems. This is unlikely to happen: there are confidentiality considerations, and herbal remedies can be obtained from so many sources, both in this country and abroad, that any appropriate monitoring mechanism would be impossibly complicated. Also, given the NHS’s sorry record of trying to co-ordinate just hospital and GP records – a very expensive failure29 – it is doubtful if the required outcome is possible.

REFERENCES

1. Leggatt J. Complementary medicine: seeking out alternatives. https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/health/alternative-medicine/3355120/Complementary-medicine-seeking-out-alternatives.html

2. The Kings Fund. How much has been spent on the NHS since 2005. https://www.kingsfund.org.uk/projects/general-election-2010/money-spent-nhs

3. British Homeopathic Association. NHS homeopathic treatment. https://www.britishhomeopathic.org/treatment/nhs-homeopathic-treatment/

4. Dahlgreen W. Many believe alternative medicines are effective. https://yougov.co.uk/news/2015/03/06/many-believe-alternative-medicine-effective/

5. NHS. Acupuncture. https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/acupuncture/

6. Homeopathic A&E https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Cg2CQqMaU1I

7. Hunt KJ, Coelho HF, Wider B, Perry R, Hung SK, Terry R, Ernst E. Complementary and alternative medicine use in England: results from a national survey. Int J Clin Pract. 2010 Oct;64(11):1496-1502. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-1241.2010.02484.x.

8. Agbabiaka TB, Spencer NH, Khanom S, Goodman C. Prevalence of drug-herb and drug-supplement interaction in older adults: a cross-sectional survey. Br J Gen Pract 2018; DOI: https://doi.org/10.3399/bjgp18X699101

9. Williamson E, Driver S, Baxter K (eds). Stockley’s Herbal Medicines Interactions. 1st edition. https://www.stonybrookmedicine.edu/sites/default/files/herbal_medicines_interactions-1.pdf

10. NICE/CKS. Depression. Prevalence. https://cks.nice.org.uk/depression#!backgroundsub:1

11. NICE/CKS. Depression. Scenario: New or initial management. https://cks.nice.org.uk/depression#!scenario

12. Williamson E, Driver S, Baxter K (eds). Stockley’s Herbal Medicines Interactions. 1st edition. p 366. https://www.stonybrookmedicine.edu/sites/default/files/herbal_medicines_interactions-1.pdf

13. NICE/CKS. Irritable bowel syndrome. Prevalence. https://cks.nice.org.uk/irritable-bowel-syndrome#!backgroundsub:2

14. NICE/CKS. Irritable bowel syndrome. Scenario: Management. https://cks.nice.org.uk/irritable-bowel-syndrome#!scenario

15. NICE/CKS. Dyspepsia – unidentified cause. Differential diagnosis. https://cks.nice.org.uk/dyspepsia-unidentified-cause#!diagnosissub:1

16. Williamson E, Driver S, Baxter K (eds). Stockley’s Herbal Medicines Interactions. 1st edition. p 321. https://www.stonybrookmedicine.edu/sites/default/files/herbal_medicines_interactions-1.pdf

17. NICE/CKS. Osteoarthritis. Scenario: Management. https://cks.nice.org.uk/osteoarthritis#!scenario

18. Williamson E, Driver S, Baxter K (eds). Stockley’s Herbal Medicines Interactions. 1st edition. p 227. https://www.stonybrookmedicine.edu/sites/default/files/herbal_medicines_interactions-1.pdf

19. Williamson E, Driver S, Baxter K (eds). Stockley’s Herbal Medicines Interactions. 1st edition. p 228. https://www.stonybrookmedicine.edu/sites/default/files/herbal_medicines_interactions-1.pdf

20. McMahon GM, Zeng X & Waikar SS. Risk Prediction Score for Kidney Failure or Mortality in Rhabdomyolysis. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173(19):1821-1827. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.9774

21. Williamson E, Driver S, Baxter K (eds). Stockley’s Herbal Medicines Interactions. 1st edition. pp194. https://www.stonybrookmedicine.edu/sites/default/files/herbal_medicines_interactions-1.pdf

22. Williamson E, Driver S, Baxter K (eds). Stockley’s Herbal Medicines Interactions. 1st edition. pp129. https://www.stonybrookmedicine.edu/sites/default/files/herbal_medicines_interactions-1.pdf

23. Cardiff Metropolitan University. Sport and Health Science Degree Courses: Complementary therapies BSc (Hons) http://www.cardiffmet.ac.uk/health/courses/Pages/Complementary-Healthcare-BSc-(Hons).aspx

24. Do herbal supplements contain what they say on the label? http://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/articles/4hX30rMYkMv9YjMTH38MY6/do-herbal-supplements-contain-what-they-say-on-the-label

25. Bosely S. Why do new medicines cost so much, and what can we do about it? https://www.theguardian.com/news/2018/apr/09/why-do-new-medicines-cost-so-much-and-what-can-we-do-about-it

26. Gov.uk. Apply for a traditional herbal registration (THR). https://www.gov.uk/guidance/apply-for-a-traditional-herbal-registration-thr#eligibility-for-thrs

27. NHS. Herbal medicines. https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/herbal-medicines/

28. Cochrane Complementary Medicine. https://cam.cochrane.org/

29. Abandoned NHS IT system has cost £10bn so far. https://www.theguardian.com/society/2013/sep/18/nhs-records-system-10bn

Related articles

View all Articles