Learning disabilities and the role of the practice nurse

Dr Gerry Morrow

Dr Gerry Morrow

MB ChB, MRCGP, Dip CBT

Medical Director and Editor, Clarity Informatics Limited

People with learning difficulties, young and old, present frequently to practice nurses. They may have a wide range of issues, which can pose challenges across diagnosis, communication, consent and preventative care. Practice nurses are a core resource to support these patients and their carers

The definition of a learning disability encompasses three core components:

- Lower intellectual ability (usually an IQ of less than 70)

- Significant impairment of social or adaptive functioning

- Onset in childhood1

Public Health England estimated that in England in 2015, there were almost 1.1 million people with learning disabilities, including 930,400 adults.2 Data from over half of primary care practice in England for 2016-2017 suggested that 1 in 218 people (0.46 per cent of the population) have a learning disability.

In 2015, 70,065 children in England with a primary need associated with learning disabilities had a statement of special educational needs or education health and care plan. Of these, 44% were identified as having moderate learning difficulties, 41% severe learning difficulties, and 15% profound and multiple learning difficulties.2

People with milder learning disabilities may be able to live independently and care for themselves, manage everyday tasks, work in paid employment, communicate their needs and wishes, have some language skills, and may have additional needs that are not clear to people who do not know them well.

People with more severe learning disabilities are more likely to need support with daily activities such as dressing, washing, food preparation, and keeping themselves safe, have limited or no verbal communication skills or understanding of others, need support with mobility, have complex health needs and sensory impairments.

Behaviour

Learning disabilities are associated with ‘behaviour that challenges' (that is behaviour which is a challenge to services, family members, or carers).3 This occurs at rates of around 5–15% in educational, health, or social care services and 30–40% in hospital settings, and can encompass:

- Aggression

- Self-injury

- Stereotypic behaviour – this can encompass rituals, compulsions, obsessions, and repetitive or stereotyped use of language

- Withdrawal

- Disruptive or destructive behaviour, which can include violence, arson, or sexual abuse, and may bring the person into contact with the criminal justice system.

The risk of 'behaviour that challenges' is increased by factors including:

- A severe learning disability

- Autism spectrum disorder

- Dementia

- Communication difficulties (expressive and receptive)

- Visual impairment (which may lead to increased self-injury and stereotypy)

- Physical health problems

- Age (incidence peaks in the teens and 20s)

- Abusive or restrictive social environments

- Environments with little or too much sensory stimulation and those with low engagement levels

- Developmentally inappropriate environments (for example, school tasks which make too many demands on a child or young person)

- Environments where disrespectful social relationships and poor communication are typical or where staff do not have the capacity or resources

- Changes to the person's environment.

Physical health

Approximately 50% of people with learning disabilities have a comorbid physical health condition. This is thought to be due to a combination of factors, including increased rates of obesity or of being underweight due to dietary factors, lack of physical exercise, and difficulties accessing healthy lifestyle advice and support; a 20-fold increased risk of epilepsy compared to background population rates; increased risk of dysphagia leading to eating and drinking problems and aspiration pneumonia; increased rates of visual and hearing impairment; increased rates of constipation, dyspepsia, thyroid disorders, eczema, and Parkinson's disease compared to background population rates; and difficulties accessing healthcare and communicating needs.

Mental health

Mental health problems are experienced by 40% of adults and around 36% of children and young people with learning disabilities. These can include:

- Anxiety

- Depression

- Phobias

- Psychosis

- Bipolar disorder

- Schizophrenia

- Dementia. There is a rate of 22% compared to 6% in the general population. Dementia is particularly prevalent in people with Down's syndrome with an earlier onset than in the general population.

Social inequality

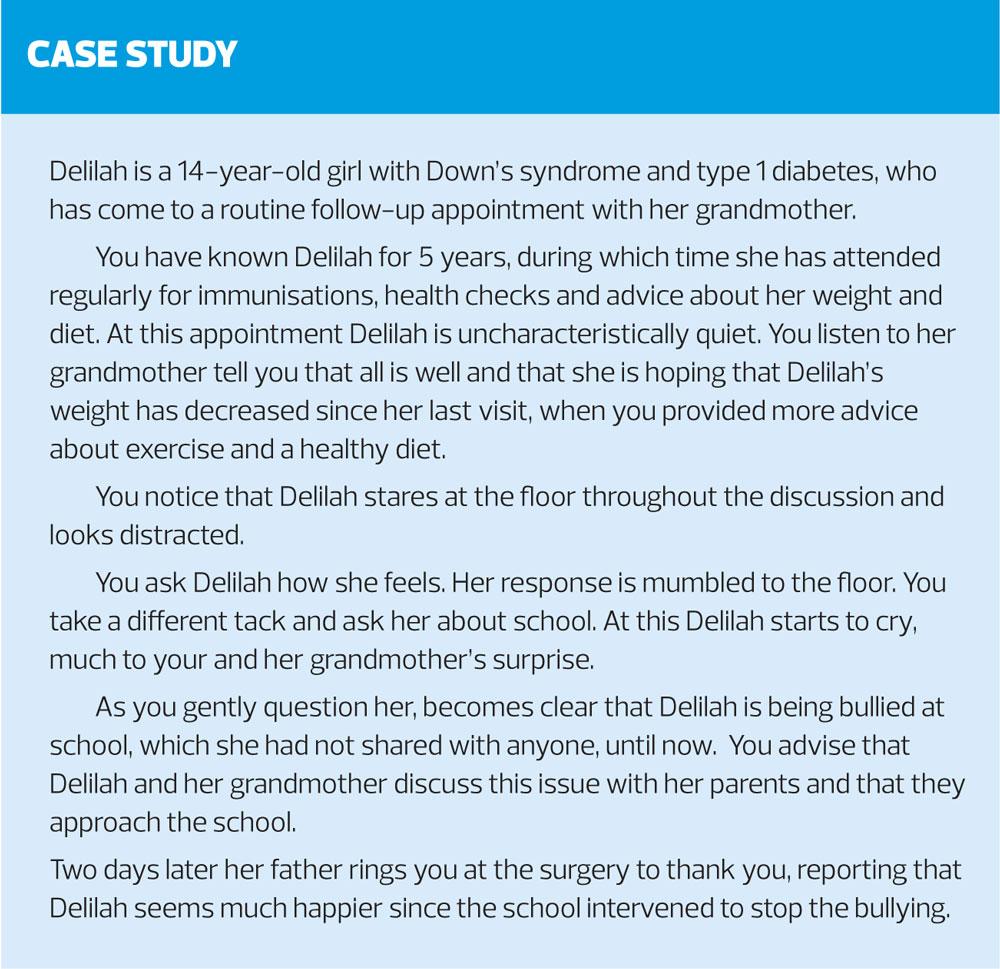

A person with a learning disability is more likely than a person in the background population to live in housing that is rented and/or overcrowded and of a poor standard. Approximately 60% of children and young people with learning disabilities live in poverty. People with a learning disability are also more likely to be exposed to tobacco smoke, and to be bullied and/or physically, sexually, or emotionally abused, and to lack social support. Children with a learning disability are also often socially excluded and more likely to be bullied.

Premature mortality

In a 2012 confidential enquiry found that men with a learning disability died on average 13 years sooner than men in the background population, while women died 20 years sooner than the female population average. Conditions associated with a learning disability (such as epilepsy, aspiration pneumonia, chromosomal disorders and associated congenital heart problems) can increase the risk of premature death, and the higher risk of inadequate or inappropriate care may also be a contributory factor to the increased mortality risk.

WHEN SHOULD I SUSPECT A LEARNING DISABILITY?

In addition to evidence of impairment of intellectual and social functioning that arose before adulthood, factors that may raise the index of suspicion for a learning disability include:

- Chromosomal and genetic anomalies, such as Down's syndrome, William's syndrome, Rhett syndrome or fragile X syndrome

- Non-genetic congenital malformations, such as spina bifida, hydrocephalus, microcephaly or neurodevelopmental problems

- Prenatal exposures to toxins including alcohol, sodium valproate, congenital rubella infection or Zika virus

- Birth complications that may have resulted in hypoxic brain injury or cerebral palsy

- Extreme prematurity (usually less than 33 weeks' gestation)

- Childhood illness, such as meningitis, encephalitis or measles

- Childhood brain injury caused by accident or physical abuse

- Childhood neglect and/or lack of stimulation in early life

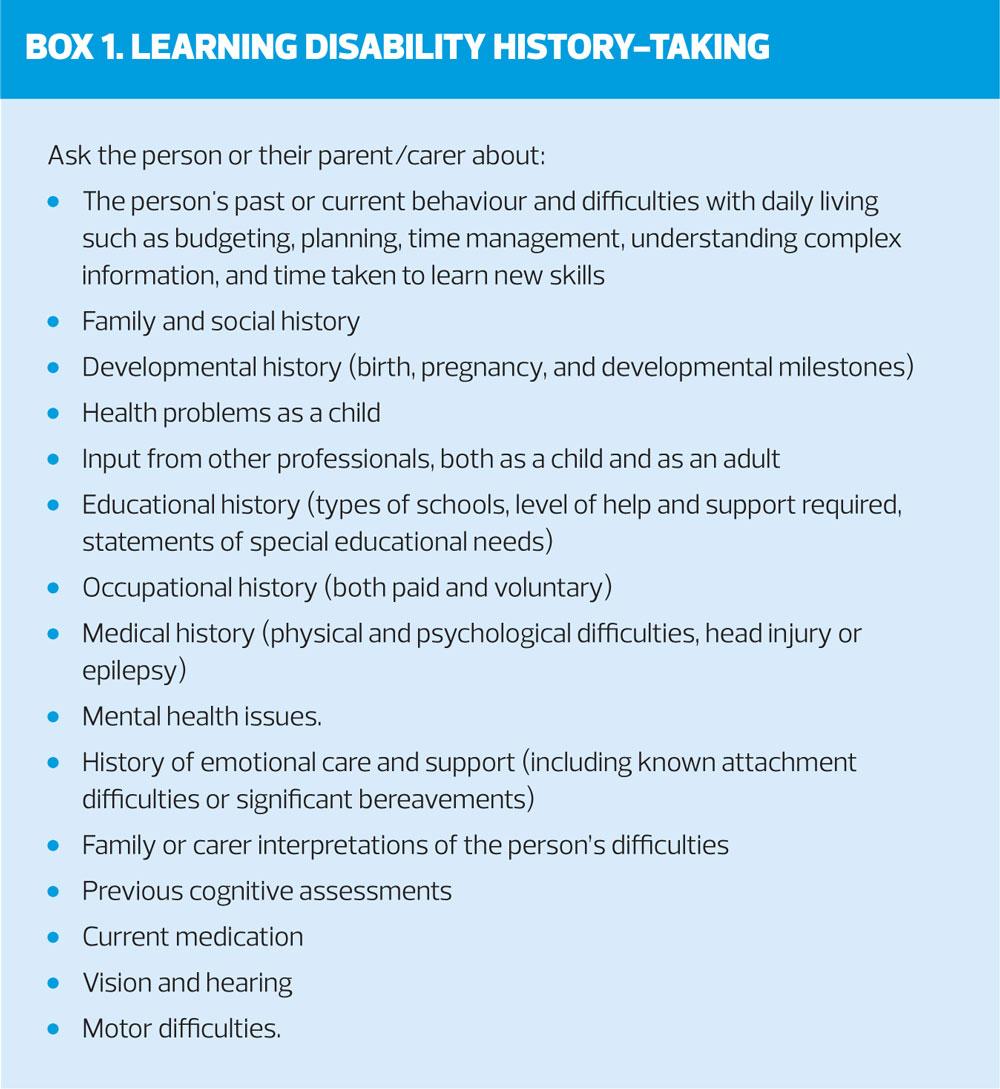

Most people with learning disabilities seen in primary care will have already received a specialist diagnosis. This may be based on neurodevelopmental assessment, and/or on a pre-existing condition for which some degree of learning disability is a component (such as Down's syndrome). In rare cases, children or adults may present in primary care with a suspected learning disability. In these circumstances it is important to take a history, bearing in mind the person's communication needs and level of understanding. (Box 1)

Wherever possible speak to the person directly rather than talking about or over them, and note factors such as eye contact, use of vocabulary, and social interaction. When interacting with a person with a suspected learning disability:

- Use clear, straightforward and unambiguous language.

- Assess whether communication aids, an advocate, or someone familiar with the person's communication methods are needed.

- Adjust your approach to accommodate sensory impairments (including sight and hearing impairments). Use different methods and formats for communication (written, signing, visual, and verbal, where possible), depending on the person's preferences.

- Communicate at a pace that is comfortable for the person.

- Regularly check the person's understanding.

HOW DO I ASSESS A PERSON'S CAPACITY TO MAKE DECISIONS?

People aged 16 years and older should be supported to make decisions for themselves when they have the mental capacity to do so and should remain at the centre of the decision-making process where they lack the mental capacity to make specific decisions.

An assessment of the person's capacity to make decisions should be personalised and should consider factors including:

- Physical and mental health

- Communication needs

- Previous experience (or lack) of decision-making

- The involvement of others and the possibility of undue influence, duress, or coercion regarding the decision

- Situational, social, and relational factors

- Cultural, ethnic, and religious factors

- Cognitive (including the person's awareness of their ability to make decisions), emotional, and behavioural factors, or those related to symptoms

- The effects of prescribed drugs or other substances

Make a written record of the decision-making process, which is proportionate to the decision being made. Share the record with the person and, with their consent, other appropriate people (such as a carer or advocate).

HOW DO I MANAGE A PERSON WITH A SUSPECTED LEARNING DISABILITY?

If a learning disability is suspected, offer a referral to the local community learning disability team for confirmation of the diagnosis and general management. Additional referral to a clinical psychologist may be necessary if the person requires assessment for purposes such as accessing benefits, determining mental capacity, and more rarely, determining fitness to plead within the criminal justice system.

Referral to mental health services (either child and adolescent or adult) may be indicated if mental health problems have been noted.

A safeguarding referral, in line with local procedures, may be needed if there are concerns regarding maltreatment or exploitation, or if the person is in contact with the criminal justice system.

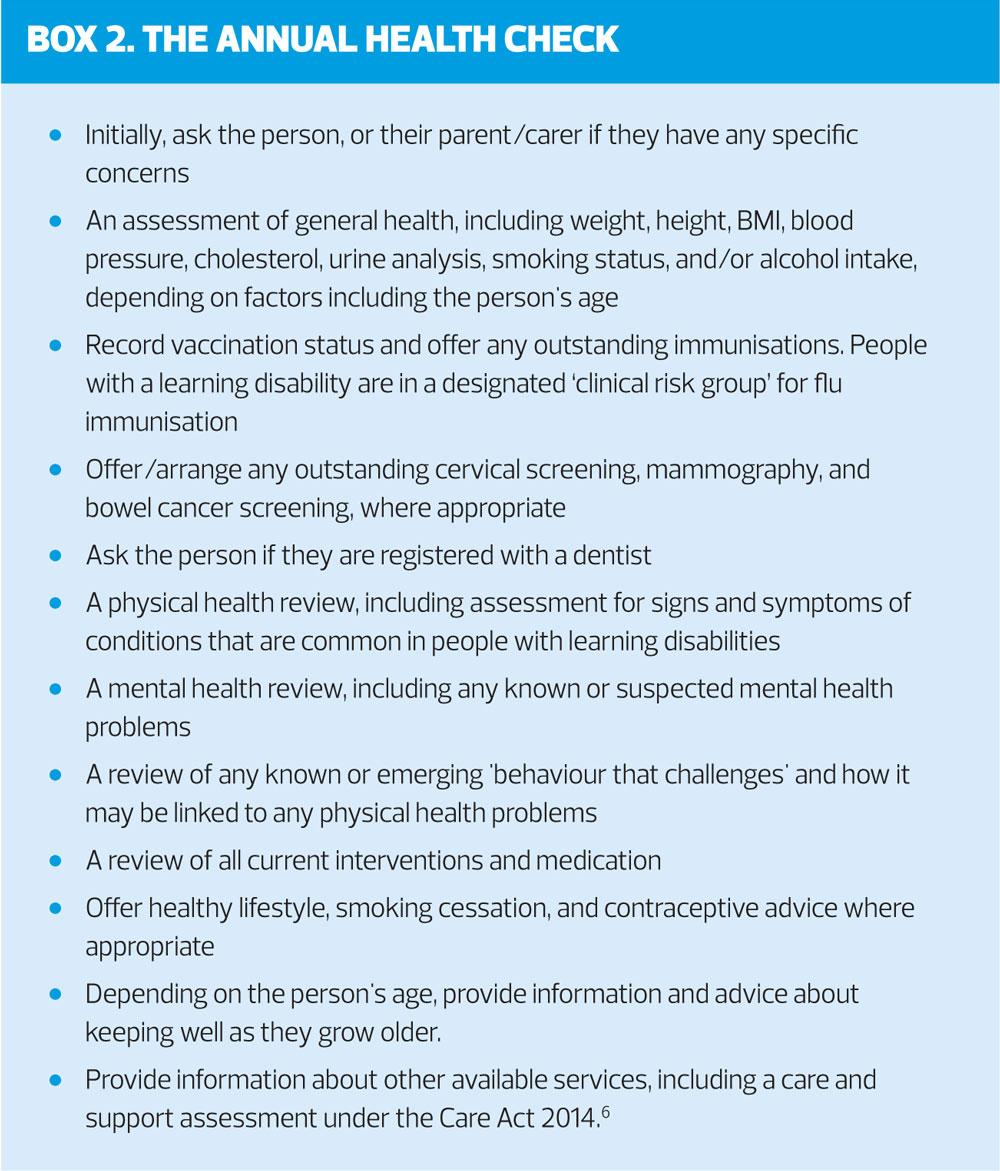

All adults with learning disabilities, and all children and young people who are not having annual health checks with a paediatrician, should be offered an annual health check in primary care.4 This should be carried out using a standardised template, such as the Cardiff health check template5 and can involve (with the person's consent) a family member, carer, care worker, or healthcare professional/ social care practitioner who knows the person well.

Be aware that people with specific syndromes may require tailored and/or additional health assessments. For example, adults with Down's syndrome should receive assessment during their annual health check of changes that might suggest the onset of dementia, such as any change in the person's behaviour, or loss of skills (including self-care).

It is important to discuss the community and specialist services that are available, especially in the transition from child to adult care.

Practice nurses should also advise family members or carers about their right to, and/or explaining how to get:

- A formal carer's assessment of their own needs (including their physical and mental health). Carers should be encouraged to register themselves as a carer, for example, with their own practice.

- Short breaks and other respite care

- Access to family advocacy

- Access to family support and information groups

- Skills training and emotional support to help them take part in and support interventions for the person with a learning disability.

Practice nurses are ideally placed to work alongside the hospital learning disability liaison nurse, and community learning disability team, to provide ongoing support to help the person manage their health condition. It may be necessary to give the person and their family members, carers, or advocate accessible information on how to take their prescribed medicines, or on end-of-life care – this may include working collaboratively and sharing information with other practitioners and services involved in the person's daily life, to ensure that their needs and wishes, including those associated with faith and culture, nutrition, hydration, and pain management are documented. This is particularly important if the person has difficulty communicating.

HOW SHOULD I MANAGE 'BEHAVIOUR THAT CHALLENGES' AND/OR A MENTAL HEALTH PROBLEM?

When managing a person with a learning disability, evaluate their capacity to make decisions throughout assessment, care, and treatment on a decision-by-decision basis, and be mindful of their communication needs. Practice nurses should regularly review the communication needs of people with learning disabilities as they grow older to find out if they have changed.7

If a child, young person, or adult with a learning disability presents in primary care with 'behaviour that challenges', or a suspected mental health problem it is essential to ask the person or their parent/carer about the following:

- Suicidal ideation, self-harm (in particular in people with depression) and self-injury

- Harm to others

- Self-neglect

- Breakdown of family or residential support

- Exploitation, abuse, or neglect by others

Where any of these are reported, a safeguarding referral or referral to an appropriate mental health specialist may be required.

Seek advice from the local learning disability support team regarding assessment of 'behaviour that challenges', as well as development of a behavioural support plan.

A mental health problem should be considered if a person with learning disabilities shows any changes in behaviour such as loss of skills or needing more prompting to use skills, social withdrawal, irritability, avoidance, agitation, and/or loss of interest in activities they usually enjoy. Practice nurses should be aware that an underlying physical health condition may be causing the problem, that a physical health condition, sensory, or cognitive impairment may mask an underlying mental health problem, and/or that mental health problems can present differently in people with more severe learning disabilities.

If a person with a learning disability has a suspected mental health problem, arrange for assessment by an appropriate mental health professional. Where serious mental illness or dementia are suspected, the person should be referred directly to a psychiatrist.

The following treatment options may be considered helpful:

- Cognitive behavioural therapy adapted for people with learning disabilities to treat depression or subthreshold depressive symptoms, in people with milder learning disabilities

- Relaxation therapy to treat anxiety symptoms

- Graded exposure techniques to treat anxiety symptoms or phobias

- Parent training programmes specifically designed for children with learning disabilities to help prevent or treat mental health problems in the child, and to support carer wellbeing

All interventions should be adjusted with reference to the impact of the person's learning disability and 'behaviour that challenges'. Ensure that the person understands the purpose, plan and content of any intervention before it starts, and regularly throughout.7

SUMMARY

People with learning difficulties, young and old, present frequently to practice nurses in primary care. These people have a wide range of issues, which can pose challenges across diagnosis, communication, consent and preventative care. Practice nurses are a core resource to support patients with learning disabilities and their carers and help to deliver holistic health care in order to add years to their life and life to their years.

REFERENCES

1. NICE NG11. Challenging behaviour and learning disabilities: prevention and interventions for people with learning disabilities whose behaviour challenges, 2015 https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng11

2. PHE Learning Disabilities Observatory People with learning disabilities in England, 2015 https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/613182/PWLDIE_2015_main_report_NB090517.pdf

3. Clinical Knowledge Summaries Learning Disabilities https://cks.nice.org.uk/learning-disabilities#!topicSummary

4. NICE QS101. Learning disabilities: challenging behaviour Quality standard, 2015 https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/qs101

5. Cardiff Health Check for people with Learning Disabilities. http://www.easyhealth.org.uk/sites/default/files/Cardiff_Health_Check.pdf

6. UK Government Legislation Archive Care Act 2014. http://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2014/23/contents/enacted

7. NICE NG54. Mental health problems in people with learning disabilities: prevention, assessment and management NICE guideline, 2016. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng54

Related articles

View all Articles