Red flag eye conditions: a guide for the practice nurse

Beverley Bostock-Cox

Beverley Bostock-Cox

RGN, MSc, QN

Nurse Practitioner Mann Cottage Surgery Moreton in Marsh

Education Lead Education for Health, Warwick

Some eye conditions present acutely, and some insidiously; some are minor and self-limiting and others are sight-threatening. Can you tell the difference and do you know when to refer urgently?

General practice nurses (GPNs) working in an advanced or autonomous capacity may find themselves involved in the diagnosis and management of eye conditions. The most common conditions seen in general practice might include a red, sore eye caused by infective or bacterial conjunctivitis. However, other, more significant eye conditions may also present in the surgery setting so GPNs should be aware of how to identify potential cases. In this article we consider how to carry out a basic assessment of the eye and recognise potential red flags, including knowing when to refer on.

ANATOMY AND PHYSIOLOGY

When assessing someone with an eye condition it is important to relate any symptoms to the underlying anatomy. This page from Action for Blind People can serve as a useful reminder of the structures of the eye and their functions: https://www.actionforblindpeople.org.uk/support-and-information-page/information/eye-health/how-the-eye-works/ (See Activity 1).

ASSESSING THE EYE

The eye consists of several different layers and structures; some are visible externally and some require more detailed examination procedures, including fundoscopy. As with any condition much of the differential diagnosis will be determined from the history, which should include information about the nature of the onset (idiopathic or trauma-related, for example); provocative and palliative factors; quality, duration, site and severity of any pain or discharge; any visual disturbances; co-morbidities; and current treatment. Once the history has been established, an examination can be carried out. However, all GPNs should only ever work within their competencies when assessing, diagnosing and treating patients and this must always be borne in mind. (See Activity 2)

Eye assessment may include:

- Assessing visual acuity using a Snellen chart (with glasses if these are normally worn)

- Visual field assessment

- Examination of eye movements – for which both muscles and nerves are responsible

- Pupil size, shape and reactions

- Establishing whether the external eye appears normal and looking for any ptosis (drooping) or lid lesions

- Examination of the ocular surface – conjunctiva

- Fundoscopic examination by a competent practitioner1

We will now discuss some of the more significant eye conditions seen in practice and identify the key defining features and red flags that GPNs should be aware of.

MACULAR DEGENERATION

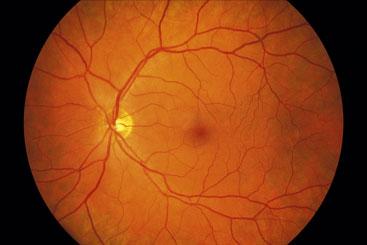

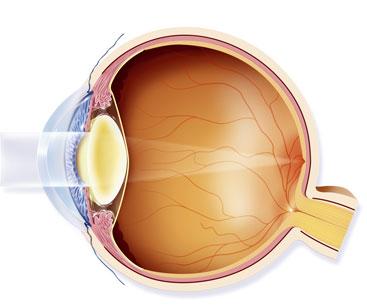

As its name suggests, macular degeneration affects the macula of the eye where light perception occurs. At the centre of the macula is the fovea where the high concentration of cones allows colour to be seen. (Figure 1)

It is a painless condition with the result that some forms of the condition can remain undetected until damage to the sight occurs. The pathophysiology of the condition means that central vision is affected while the peripheral vision remains intact.

The most common type of macular degeneration is age related (known as age-related macular degeneration or AMD) and occurs in the over 60s as the retinal cells wear out and fail to regenerate. There are two type of AMD – wet and dry – with 90% of cases being of the dry kind.2 Dry AMD can develop over years, whereas wet AMD is related to the development of new blood vessels (neovascularisation) leading to bleeds within the eye. Wet AMD therefore tends to be acute in onset and requires swift referral to hospital for treatment and to assess suitability for treatment. Around one in ten people who are known to have dry AMD can go on to develop wet AMD, so any unexpected visual symptoms should be addressed without delay; it is also possible to have wet AMD in one eye and dry AMD in the other.

The Macular Society lists some of the key symptoms that people with AMD might notice, although they point out that many people will be asymptomatic for years, especially if only one eye is affected.

Possible symptoms of AMD include:

- Objects appearing distorted, changing shape, size or colour

- Things appearing to move or disappear e.g. words on a page

- Gaps or dark spots in the centre of the vision

- Discomfort in bright light

- Difficulty adjusting from dark to light environments. (See Activity 3)

The diagnosis of dry AMD may be delayed because of the gradual onset of symptoms. Tools such as the Amsler grid can identify people with AMD and may also be used to assess any changes in people who are already diagnosed. (See Activity 4)

Some forms of wet AMD can be treated with anti-vascular endothelial growth factor (anti-VEGF) injections to the eye, aimed at reducing the level of neovascularisation. Sometimes laser treatment may be offered if injections are not suitable. Patients are understandably anxious about having eye injections. Have a look at this video from the Royal National Institute for the Blind about a patient’s experience of having anti VEGF injections.

The risk of AMD may be increased if there is a family history and lifestyle advice is recommended for people with, or at risk of AMD. Recommended interventions include eating a low saturated fat diet with plenty of green leafy vegetables. This may reduce the risk. Limiting alcohol to recommended target levels and avoiding smoking also seems to help.

GLAUCOMA

The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) published guidance on the diagnosis and treatment of glaucoma in 2009 and this is currently being updated with specific reference to chronic open angle glaucoma.3 The new guidelines are expected later this year.

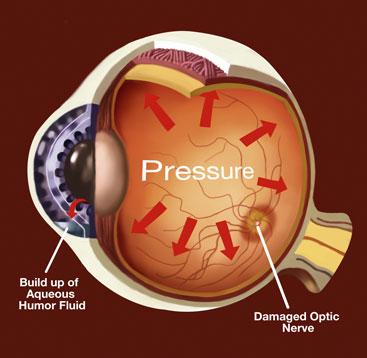

Glaucoma occurs when changes in the eye damage the optic nerve (Figure 2). These changes might include raised pressure within the eye or pathology in the nerve itself. Pressure changes within the eye may happen over a long period of time or acutely. Acute glaucoma is often very painful, with acute changes in vision and symptoms such as vomiting. Acute glaucoma has the ability to cause significant visual loss, including permanent blindness, in a short period of time, whereas chronic glaucoma is more likely to be painless with the classic tunnel vision changes happening gradually.4 However, ignoring the changes in chronic glaucoma can also lead to permanent loss of sight.

Glaucoma is rare under the age of 40 and is more likely when there is a family history of the condition. Anyone over 40 with a family history of glaucoma will be entitled to free annual checks. Myopia (short-sightedness) and diabetes are also risk factors for glaucoma. Treatment options include beta-blocker eye drops aimed at reducing intra-ocular pressure, surgery (trabeculectomy) to improve fluid drainage in the eye, or laser treatment.

A patient presenting with an acutely painful eye should be referred to hospital without delay, especially if visual changes are reported (coloured rings around any bright lights are often described by patients with acute glaucoma).

DIABETIC RETINOPATHY

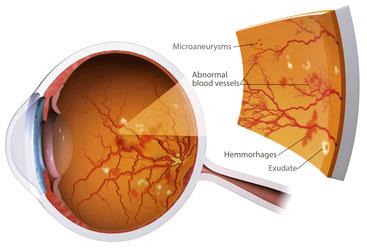

Around 40% of people with type 1 diabetes and 20% of those with type 2 have diabetic retinopathy (DR) although the longer the duration of diabetes the higher the risk of developing DR.5 The changes to the retina that occur with DR (Figure 3) are often related to sub-optimal control of blood pressure or glycaemic levels.6

Annual retinal screening is vital to detect early changes before they become more significant and sight-threatening. The success of the retinal screening programme has meant that the leading cause of blindness in working age people is no longer DR but congenital eye disease.7 (See activity 5)

DR is caused by thickening of the capillary basement membrane, which causes leakage of protein and changes to the circulation within the eye. There are three main stages:

1. Background DR

2. Diabetic maculopathy

3. Proliferative changes.

Each change is more significant than the last, so again, early identification and management is vital.8

CATARACTS

Cataracts are the result of changes in the lens of the eye (Figure 4), leading to blurred or misty vison, which develops over years, usually – but not exclusively – in people over 65. People who have a history of eye problems or surgery may be at greater risk of cataracts, as may those who have used high or prolonged doses of corticosteroids. Smoking, poor dietary habits and excess alcohol intake are also linked to an increased risk of cataract development.

Visual changes with cataract can be similar to those that occur in AMD. Colours may appear less bright and street or car lights may be uncomfortable to look at or appear to have a haze around them, but often the symptoms are simply a gradual deterioration in vision. Cataract surgery will be carried out when loss of vision is interfering with activities of daily living. Most people can be treated as a day case and will find that their sight improves within days or weeks.9

EYE EMERGENCIES

Patients will need to be referred to A&E or the emergency eye clinic without delay if they present with any of the following:

- Sudden loss of vision

- Sudden visual changes with or without pain

- Suspected acute glaucoma

- Penetrating injury/intraocular foreign body

- Chemical burn

- Corneal ulceration

- Retinal detachment.10

Retinal detachment

The symptoms of retinal detachment include the sudden appearance of floaters, flashes or distorted vision which then develops into a ‘black curtain’ which moves across the field of vision.11 Patients with these symptoms should be referred urgently as they are at risk of blindness.

Retinal detachment is more common in older people in their 60s and 70s but can also occur after injury. Treatment to reattach the retina is often successful but the length of time before treatment is initiated can influence success rates.

CONCLUSION

Problems affecting the eyes can range from relatively straightforward cases of conjunctivitis to sight-threatening problems. As many GPNs are now working at an advanced level and may be seeing people who present with eye symptoms it is important to be able to assess for any red flags and act accordingly. Any delay in recognising and referring for conditions such as retinal detachment or wet macular degeneration could be life changing for the patient. GPNs working in an extended role should therefore be able to identify the anatomical structures of the eye, be able to take a structured approach to assessing and examining the eye, and be able to recognise red flags and refer on appropriately.

REFERENCES

1. Bargiela D. Examination of the eye. 2017 http://geekymedics.com/eye-examination-osce-guide/

2. Macular Society. Age related macular degeneration. 2017 https://www.macularsociety.org/age-related-macular-degeneration

3. NICE. Glaucoma diagnosis and management.2009 https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg85

4. Royal National Institute of Blind People/Royal College of Ophthalmologists. Understanding glaucoma.2016 http://www.rnib.org.uk/sites/default/files/Understanding_Glaucoma_0.pdf

5. Kohner EM (2008) Microvascular disease: what does UKPDS tell us about diabetic retinopathy? Diabetic Medicine 2008; Aug 25; Suppl 2: 20-4.

6. Gaede P, Lund-Andersen H, Parving HH, Pedersen O. Effect of a multifactorial intervention on mortality in type 2 diabetes. New England Journal of Medicine 2008; 358(6): 580-591

7. Liew G, Michaelides M, Bunce C. A comparison of the causes of blindness certifications in England and Wales in working age adults (16–64 years), 1999–2000 with 2009–2010 BMJ Open, Opthalmology 2014; Vol 4 Issue 2 Available at http://bmjopen.bmj.com/content/4/2/e004015.full

8. Action for Blind People. Diabetic retinopathy 2015-17 https://www.actionforblindpeople.org.uk/support-and-information-page/information/eye-health/eye-conditions/diabetic-retinopathy/

9. Fight for sight. Cataract – what is it? 2015 http://www.fightforsight.org.uk/about-the-eye/a-z-eye-conditions/cataract/

10. Practice Nurse. Eye conditions. 2015 http://www.practicenurse.co.uk/index.php?p1=a-z&p2=eye-conditions

11. NHS Choices (2015) Retinal detachment http://www.nhs.uk/conditions/Retinal-detachment/Pages/Introduction.aspx

Related articles

View all Articles