Frailty, a long-term condition

Rachel Viggars

Rachel Viggars

RN Dip HE BSc (Hons)

Specialist Practice-GPN. Advanced Nurse Practitioner, Ashley Surgery (North Staffordshire CCG)

Dr Andrew Finney

RN, Dip, BSc (Hons) PGCHE, PhD.

Lecturer in Adult Nursing and Post-Doctoral Research Fellow. Programme Lead for the Fundamentals in General Practice Nursing, Keele University School of Nursing and Midwifery and Research Institute for Primary Care and Health Sciences.

Frailty is now recognised as a long term condition and its management should follow a similar pathway to that of other LTCs, with general practice nurses playing a central role in the care of their frail, elderly patients

The condition of frailty is now seen to meet the criteria for a long term condition (LTC).1 General practice is the first point of contact to deliver the management for the traditional LTCs such as diabetes, ischaemic heart disease, asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and the condition of frailty can be managed in a similar way.

General practice nurses (GPNs) can not only influence the perception of frailty as an LTC, but also play a role in the identification and assessment of frailty to provide appropriate interventions. The ‘frailty fulcrum’2 which is discussed here provides a resource for improving awareness and understanding of the impact on frailty on our patients.

WHAT IS FRAILTY?

The British Geriatric Society (BGS) defines frailty as ‘a distinctive health state related to the ageing process in which multiple body systems gradually lose their built-in reserves’.3 Older people living with frailty are at risk of adverse outcomes including changes in their physical and mental wellbeing after an apparently minor event, which challenges their health, such as an infection or new medication.3

Frailty is associated with ageing although it is not an inevitable process and its severity may fluctuate over time.4 There is now significant effort which seeks to promote the clinical diagnosis of frailty as an LTC and to facilitate its management in primary care.5 This is supported by a focus in the GP contract to do just that, using validated tools such as the electronic Frailty Index (eFI) alongside clinical judgment to identify patients who may be living with frailty.6

Resilience vs vulnerability

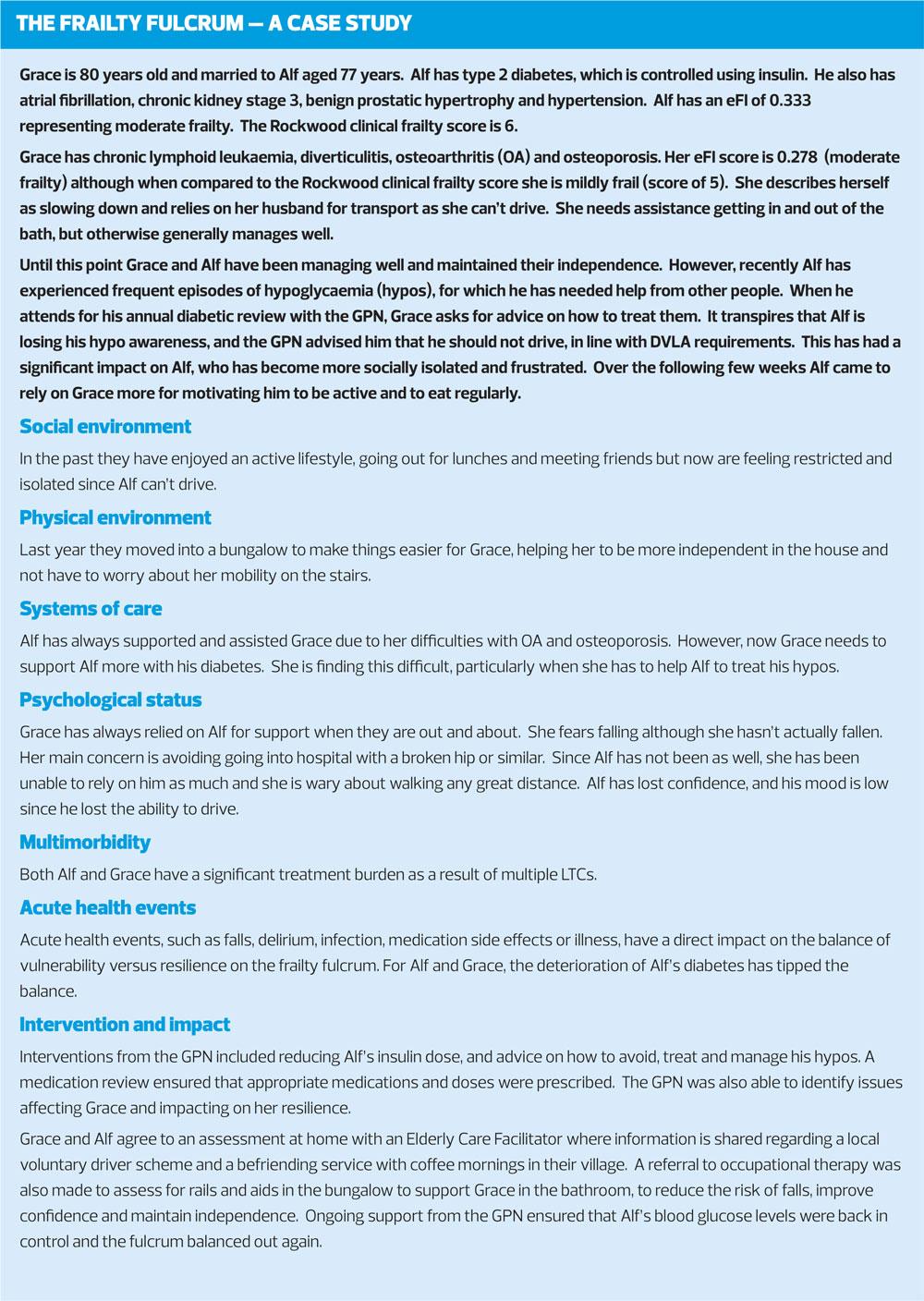

It is recognised that a small change or event in a person living with frailty may trigger major changes in health and well-being.7 This has the potential to have a significant impact on the person in that they may not succeed in returning to their previous level of health. The Frailty Fulcrum provides a model of shared understanding for patients, carers and health care professionals.2 As frailty is related to reduced function, the fulcrum shows how the impact of changes in a person’s circumstances can change the balance of their quality of life. These changes cover the six domains: social environment, physical environment, psychological status, LTCs, acute health events and systems of care.

THE ELECTRONIC FRAILTY INDEX (eFI)

The electronic Frailty Index (eFI) is a validated tool already available in primary care electronic health records.7 It is a cumulative deficit model which focuses on physical status and determinants of frailty using at least 36 deficits which are sensitive to change. These combine to construct a valid frailty index and should be used as a risk stratification process and not a diagnostic entity. This index can effectively identify specific adults with levels of frailty who have multimorbidity, who may therefore be at risk of unplanned admissions, and who may benefit from early intervention. Such intervention may include falls risk assessment, occupational therapy or physiotherapy input, rationalisation of prescribed medicines to reduce side effects, in addition to social prescribing to reduce social isolation and loneliness. However, one potential disadvantage of this tool is that the quality of READ coding affects the validity of the eFI. The tool can only be as good as the information that is added to the patient records by the clinician, and so systematic coding using templates will assist in ensuring that the appropriate data are collated. The eFI aids understanding of the practice population and provides the impetus to target intervention.8 It is a method of highlighting the levels of frailty in the practice population in order to plan care, and has been specifically designed to classify mild, moderate and severe frailty.9

- Fit: eFI score = 0-0.12

- Mild frailty: eFI score = 0.13-0.24

- Moderate frailty: eFI score = 0.25-0.36

- Severe frailty: eFI score ≥ 0.3612

These classifications demonstrate a continuum of ‘fit well adults’ who are independent in day to day activities and have minimal health concerns to the opposite end of the spectrum with severe frailty representing people with significant dependence for personal care and who have a range of LTCs.

Recent eFI data from primary care settings, suggests overall frailty prevalence in the average practice population is almost 40% (25.8% mild frailty, 10.2% moderate frailty and 2.7% severe frailty).10 This demonstrates a significant workload in order to address the needs of people living with frailty with the implementation of specific interventions and management.

There will be a growing need to target interventions for those living with frailty not only to reduce hospital admissions but also to ensure that people can live well with frailty with the support and management that is required.11 This provides the impetus to target intervention, enabling people to not only live well with frailty, but to have the appropriate support ensuring that this can be facilitated in accordance with the patient’s wishes. In addition to this, the BGS guidelines advise that all patients with frailty should have a holistic medical review and that frailty may not be apparent unless actively sought’.12

The eFI provides a system to enable this to be undertaken opportunistically but also as a planned audit if that suited the locality. However, the GP Contract for 2017-18 warned of the risk of ‘batch coding’ eFI scores into a patient’s record without applying the necessary clinical judgment.13 For this reason, it is recommended that further diagnostic tools should be used to support decision making. It should be noted that although the current BGS advice is not to offer routine population screening, as awareness grows of frailty and its implications, it will be vital to have a working understanding of the importance of supportive tools to be used in conjunction with the eFI.

A CLINICAL FRAILTY SCALE

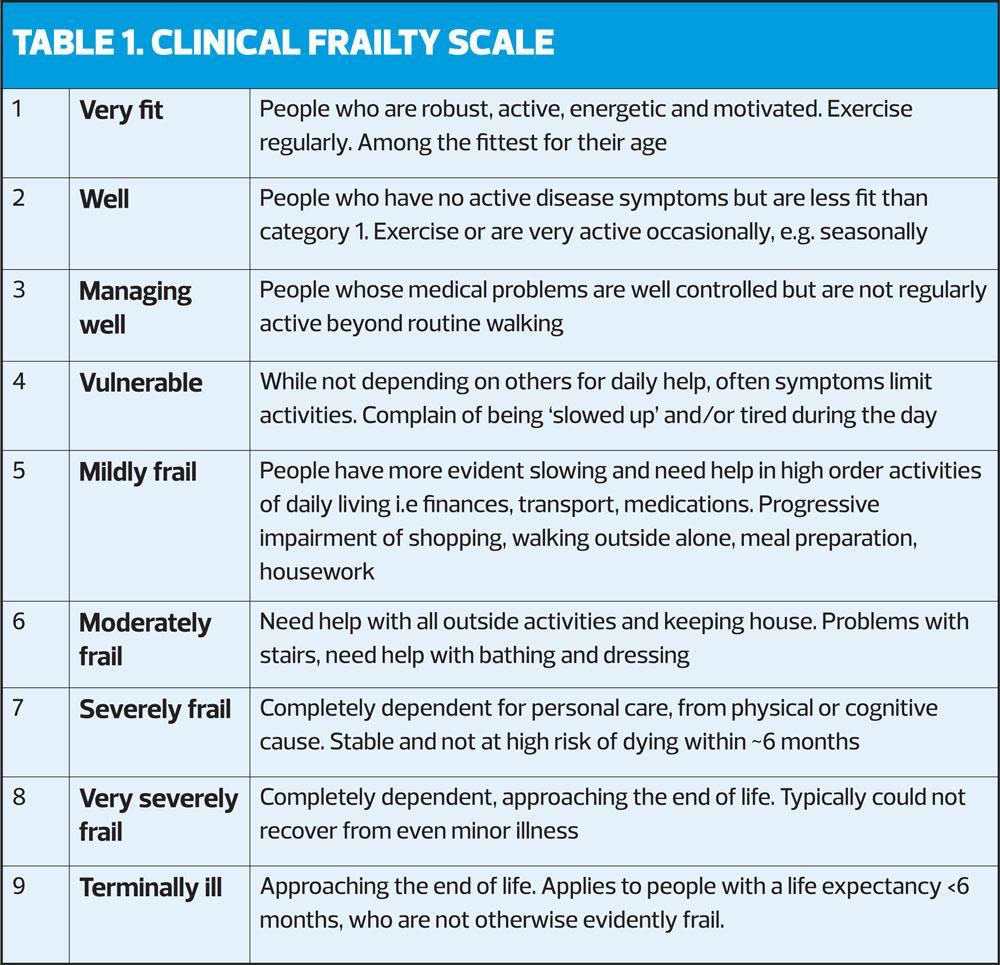

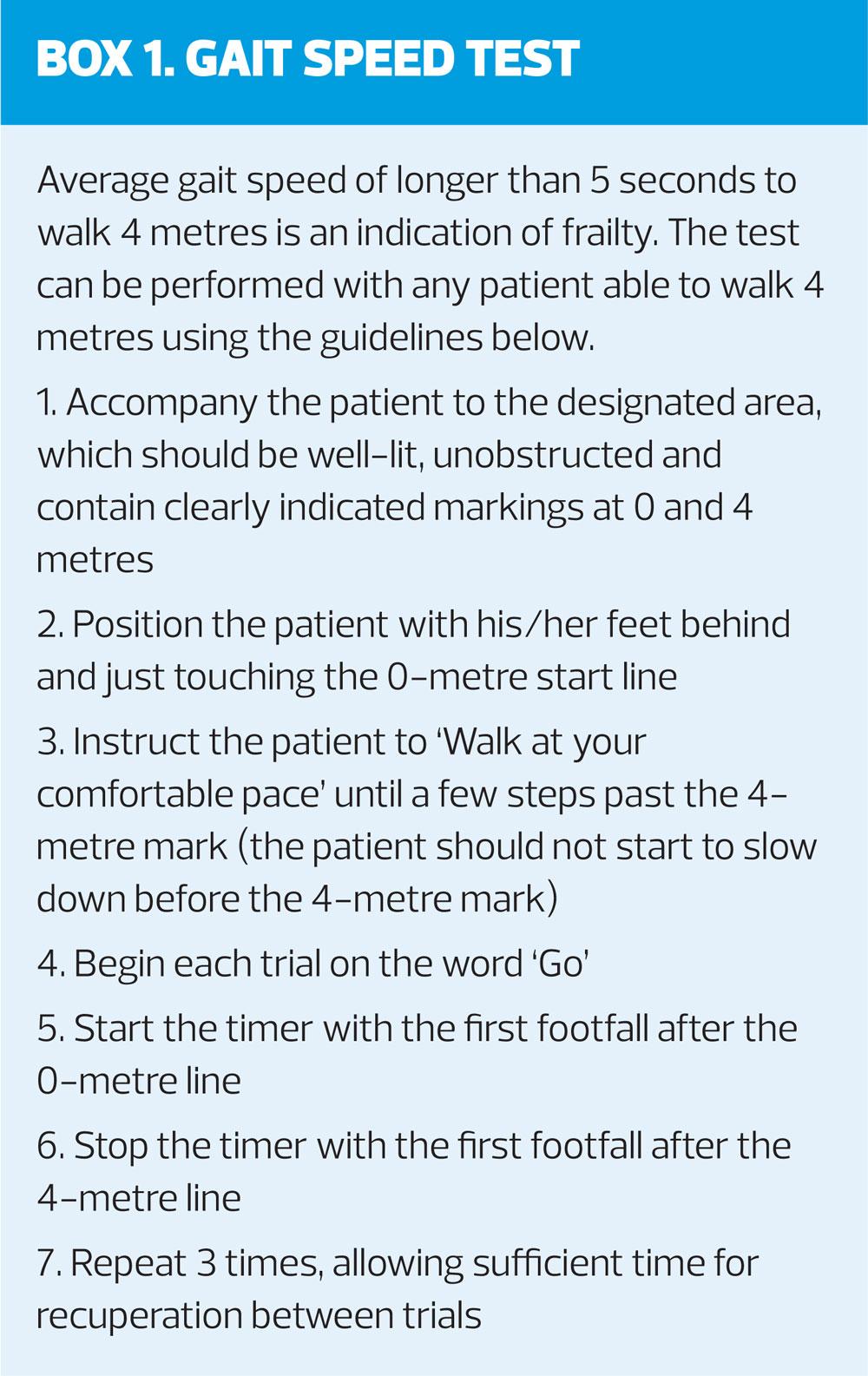

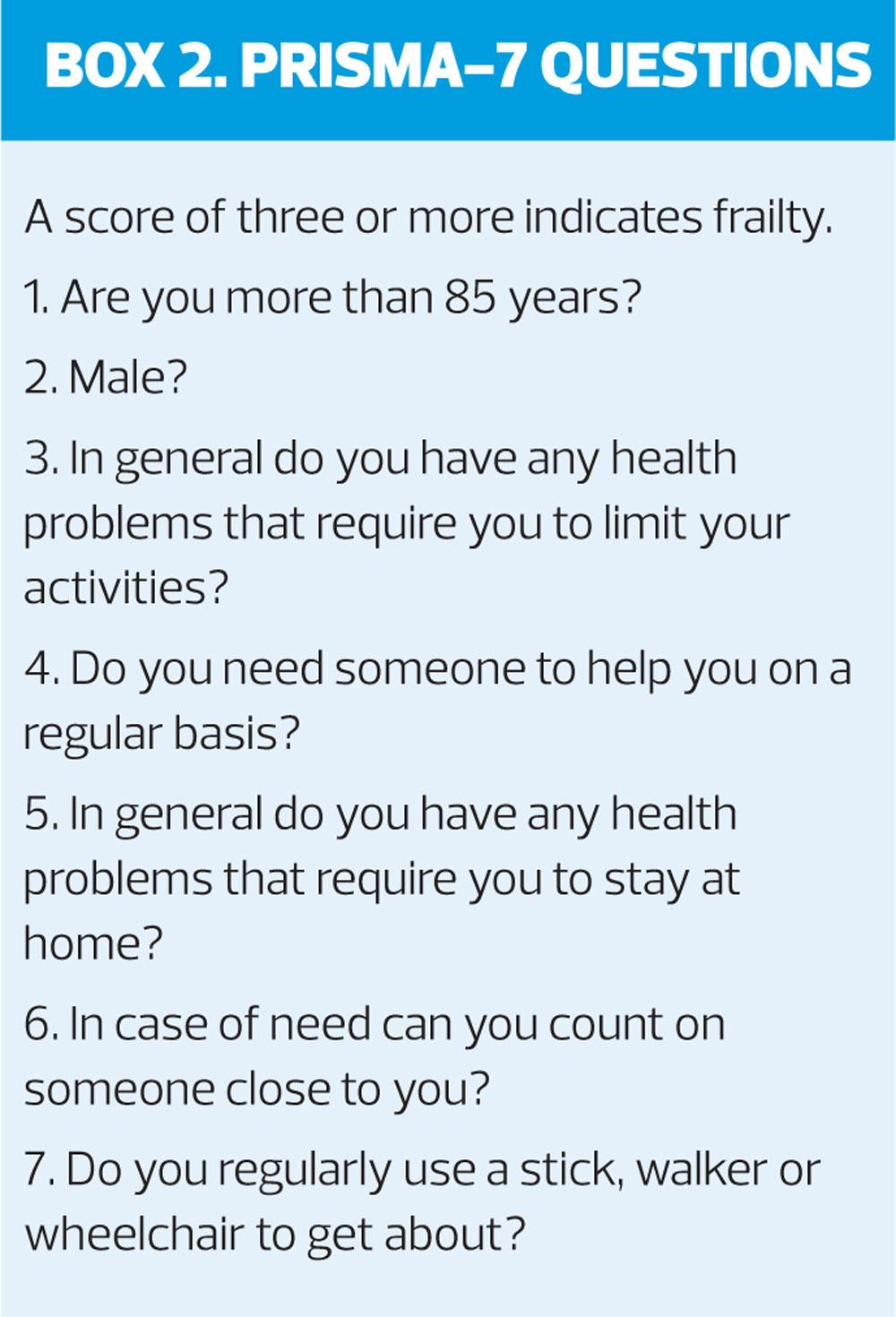

NHS England has developed a frailty toolkit to support general practice to undertake case finding and it outlines a number of tools that can be used, including the Rockwood Clinical Frailty Scale (Table 1), the gait speed test (Box 1) or the PRISMA-7 questions (Box 2).14

The clinical frailty scale is a simple nine-point scale which has proved to be useful for frailty identification in clinical settings.15 If used in conjunction with the eFI, the clinical frailty scale enables a classification of frailty that is patient focused and not solely based on coding. The clinical frailty scale is a functional tool that can be easily applied to patients in any context when the eFI highlights a level of frailty, thus simplifying classification.

A problem we have in general practice is that as part of the Quality and Outcomes Framework (QOF) we generally use a single disease-focused management approach with LTCs, but frailty crosses borders of medical, social and psychological elements.5 This suggests that a focus-based approach to the health and social integration of care is required, where care must be co-ordinated and person-centred. This co-ordinated model would ensure that the appropriate care was delivered at the right time and by the right services.16 With the current Government agenda of trying to reduce hospital admissions, frailty management could be started at a very early stage of the frailty continuum. Frailty classifications such as eFI and Clinical Frailty Score can be useful for practices to plan care appropriate to the need of their specific patients. The right approach will vary depending on the locality and demographics of the practice population, but effective integrated care is the key to ensure people are living well with LTCs, complex co-morbidities and frailty.16

LTC management already accounts for 70% of all NHS spending, and represents 55% of all GP appointments.17 NHS England and Age UK have designed a self-management guide targeted at people with mild frailty.18 This is an ideal resource for GPNs to attempt to educate and support people in order to age well. GPNs are ideally placed to work with this group, providing the necessary healthy lifestyle support as this overlaps much of the current LTC work that they already do.

FRAILTY: CORE CAPABILITES FRAMEWORK (CCF)

It is essential that there is appropriate training in frailty recognition for all general practice staff to facilitate integrated team working.12 Innovative ways of working, for example the introduction of an Elderly Care Facilitator into the practice team, could enable effective case management, self-management support and signposting to appropriate services. This model has been shown to be very successful with a reduction in GP workload, and is not only cost-effective but also beneficial to the patient population.19 The 5-year forward view20 focuses on a more integrated approach to working and the need to up-skill the workforce to work cost-effectively and to be clinically efficient. However, organisational change, effective training and adequate funding are needed to support the management of frailty as an LTC.

The Core Capabilities Framework (CCF), published in 2018,21 provides a consistent and comprehensive approach to developing and educating practice staff, volunteers and families/carers. Recent research has shown a need for a fundamental change in the currently inconsistent and variable provision of training and education for frailty.22

CONCLUSION

Frailty remains a relatively new area for much of the GPN workforce and work is now needed to position frailty as an LTC, underpinned by an up-skilling of the workforce. Use of the eFI in general practice, alongside a tool such the CCF ensures that significant advances in the care of people who live with frailty can be achieved. The CCF aims to identify and describe the skills, knowledge and behaviours required to deliver high quality, holistic, compassionate care and support. It provides a single, consistent and comprehensive framework on which to base review and development of staff.

The potential and opportunity to make a difference to the quality of life for these patients is huge. It is hoped that the development of effective integrated care will target supported self-management for those patients identified with mild frailty, to provide better health outcomes and the ability to age well. Furthermore GPNs can proactively look for patients with moderate or severe frailty who may be appropriate for advanced care planning and the support of integrated services in order to reduce hospital admissions. One area that remains to be addressed is how this additional work will be funded through a primary care system that is already under strain. Innovative ways of working will need to be developed to suit the individual area and demographics, while taking into account the available provision of voluntary support networks in addition to the NHS resources.

REFERENCES

1. Harrison JK, Clegg A, Conroy SP, et al. Managing frailty as a long-term condition. Age & Ageing 2015; 44(5): 732-735.

2. Moody D. The Frailty Fulcrum, 2016. https://www.england.nhs.uk/blog/dawn-moody/

3. British Geriatric Society. Introduction to frailty, Fit for frailty Part 1, 2014. https://www.bgs.org.uk/resources/introduction-to-frailty

4. Clegg A, Young J, Lliffe S, et al. Frailty in older people. Lancet 2013;381(9868): 752.

5. De Lepeleire J, Lliffe S, Mann E, Degryse JM. Frailty: an emerging concept for general practice. Brit J Gen Pract 2009;59(562);e177-82

6. NHS England. NHS Standard Contract, 2017. https://www.england.nhs.uk/nhs-standard-contract/17-18/

7. Clegg A, Bates C, Young J, et al. Development and validation of an electronic frailty index using routine primary care electronic health record data. Age & Ageing 2016;45(3):353-360

8. Gale CR, Cooper C, Aihie Sayer A. Prevalence of frailty and disability: findings from the English Longitudinal Study of Ageing. Age & Ageing 2015;44(1):162-165.

9. Young J. Living with Frailty: A Guide for Primary Care. British Journal of Primary Care Nursing 2015;12(1). https://www.bjpcn.com/browse/example-special-edition/item/1854-living-with-frailty-a-guide-for-primary-care.html

10. Reeves D, Pye S, Ashcroft DM, et al. The challenge of ageing populations and patient frailty: can primary care adapt? BMJ 2018;362:k3349

11. Public Health England. National General Practice Profiles, 2018. https://fingertips.phe.org.uk/profile/general-practice

12. British Geriatric Society. Frailty: what's it all about? Good practice guide, 2018. https://www.bgs.org.uk/resources/frailty-what’s-it-all-about

13. NHS England. GP contract requirements for the identification and management of people with frailty – guidance on batch coding, 2017

14. NHS England. Toolkit for General Practice in supporting older people living with frailty, 2017 https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/toolkit-general-practice-frailty.pdf

15. Dalhousie University. The Clinical Frailty Scale (The Rockwood Score), 2015. https://www.dal.ca/sites/gmr/our-tools/clinical-frailty-scale.html

16. Oliver D, Foot C, Humphries R. Making our health and care systems fit for an ageing population. Canadian Geriatrics Journal 2014;17(4):136-139

17. NHS England. House of Care – a framework for long term condition care, 2018. https://www.england.nhs.uk/ourwork/clinical-policy/ltc/house-of-care/

18. NHSE & AGE UK. A practical guide to healthy ageing, 2015. https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/hlthy-ageing-brochr.pdf

19. Edwards B, Sutton E. Report: Elderly Care Model for Newcastle-under-Lyme: one year on, 2018. https://moderngov.newcastle-staffs.gov.uk/documents/s25638/Elderly%20Care%20Model%20Newcastle%2012%20monthupdateESforboroughcouncil%202%202.pdf

20. NHS England. 5 year forward view, 2014. https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2014/10/5yfv-web.pdf

21. Skills for Care. Frailty: A framework of core capabilities, 2018. http://www.skillsforhealth.org.uk/images/projects/frailty/Frailty%20framework.pdf?s=form

22. Burger S, Hay H, Casanas I, et al. Exploring education and training in relation to older people's health and social care. A report prepared for: Dunhill Medical Trust, 2018. https://dunhillmedical.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/18-08P1.pdf

Related articles

View all Articles