Recognising and managing malnutrition in COPD

Beverley Bostock-Cox

Beverley Bostock-Cox

RGN, MSc, MA, QN

Editor in chief, Practice Nurse

Nurse Practitioner, Mann Cottage Surgery, Moreton-in-Marsh

Asthma lead, Association of Respiratory Nurse Specialists

Mandy Galloway

Editor

One-in-five people with COPD are at risk of malnutrition, which can lead to reduced lung function, more frequent hospital admissions, longer hospital stays and increased mortality but these outcomes can be improved with the right management

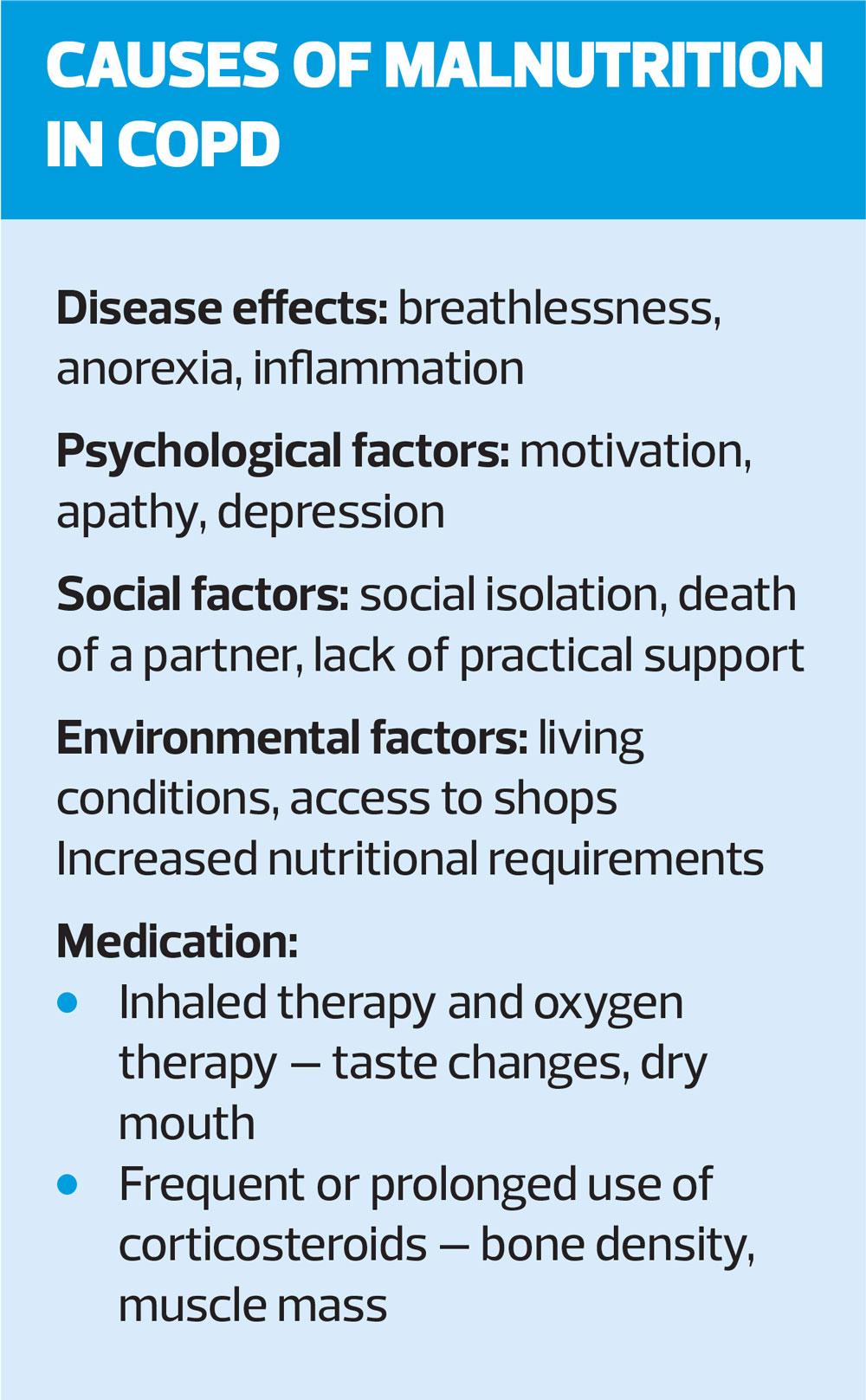

When supporting people with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) to stay as well as possible, the focus in general practice is often on lung function and inhaled therapies, along with advice on pulmonary rehabilitation and immunisations. However, around one-in-five people with COPD are at risk of malnutrition and in the busy, time-limited COPD review, this risk may be overlooked.

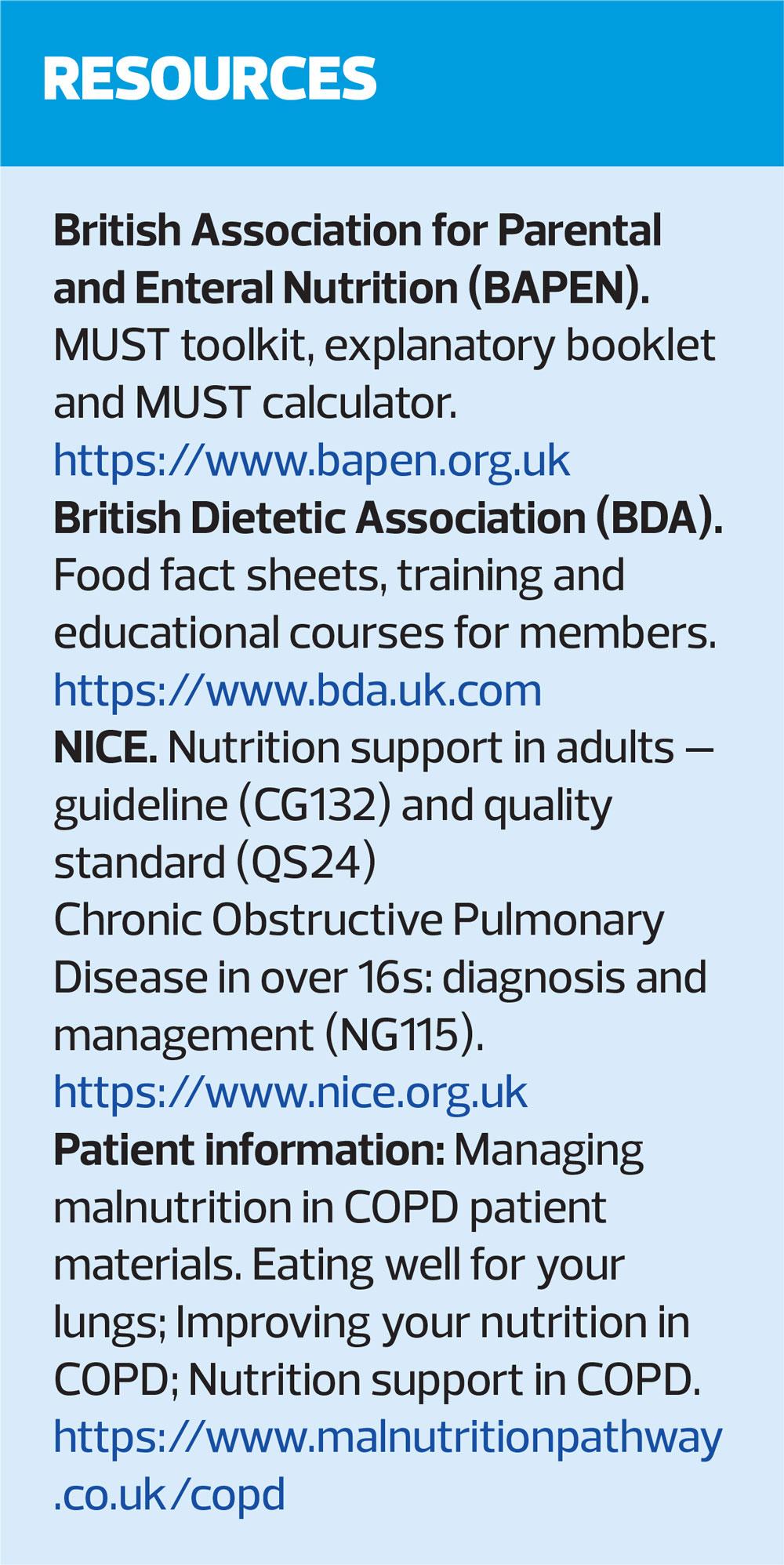

Recently a multi-disciplinary group of professionals updated a useful resource to make it easier for general practice nurses (GPNs) and others to carry out a competent assessment of this risk and take appropriate action when indicated.

The evidence-based ‘Managing Malnutrition in COPD’ guidance for healthcare professionals includes simple algorithms and patient information leaflets to support nutrition screening and to facilitate the introduction of nutritional management pathways for patients with COPD.1

DEFINITION

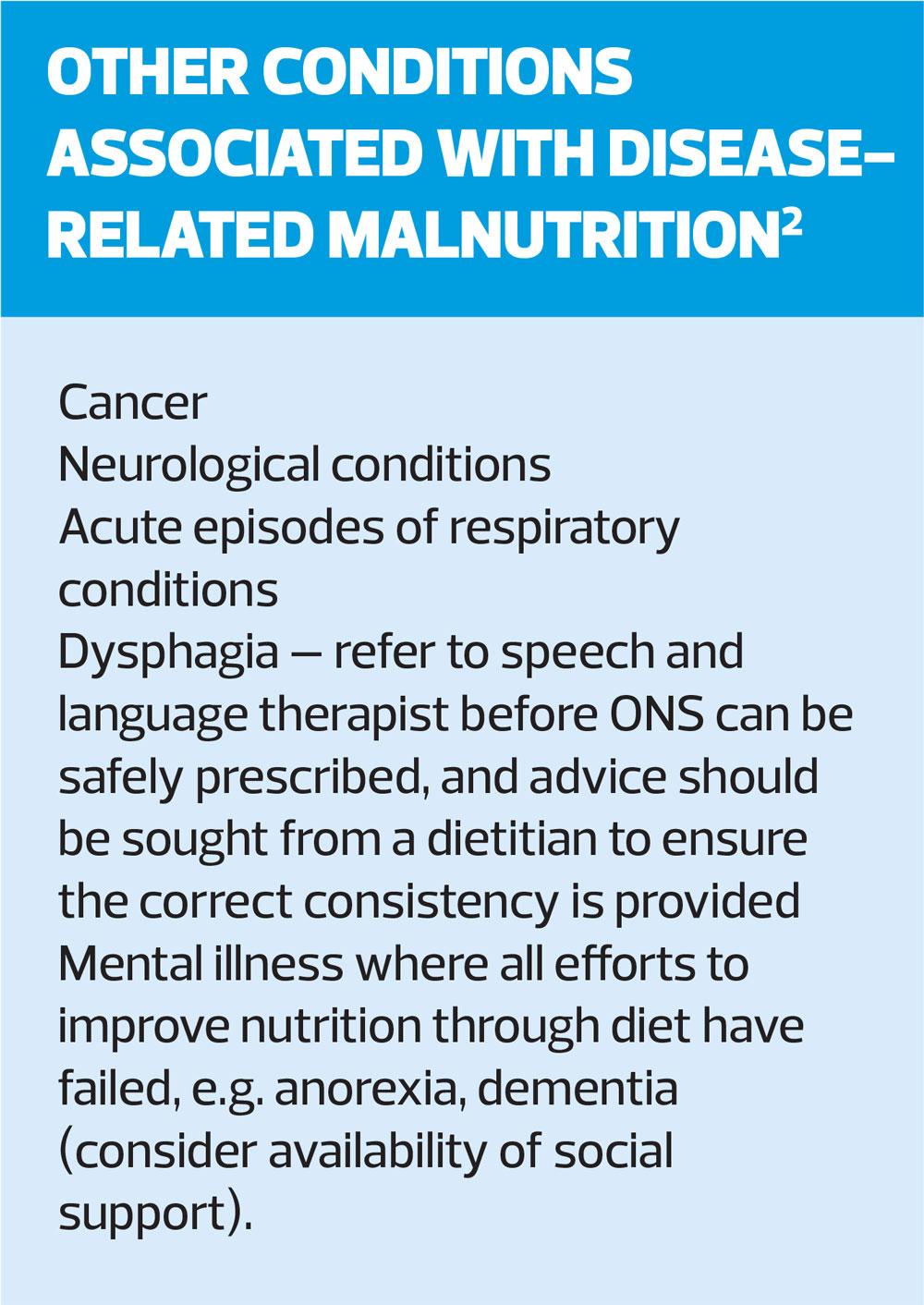

Malnutrition is defied as an imbalance of energy, protein and other nutrients that causes adverse effects on body shape, size and composition, the way in which it functions, and clinical outcomes. Malnutrition is associated with significantly higher emergency hospitalisation and up to twice the usual duration of hospital stay.2,3

Malnutrition may develop gradually over a number of years in patients with COPD, or develop more quickly or progress following exacerbations. Sarcopenia (loss of skeletal mass and strength) affects 15% with stable COPD, and about 25% of patients with COPD will develop cachexia (loss of lean tissue mass due to chronic illness).4,5

Low body mass index (BMI) and, particularly, low muscle mass are associated with worse outcomes in people with COPD.

RECOGNISING MALNUTRITION

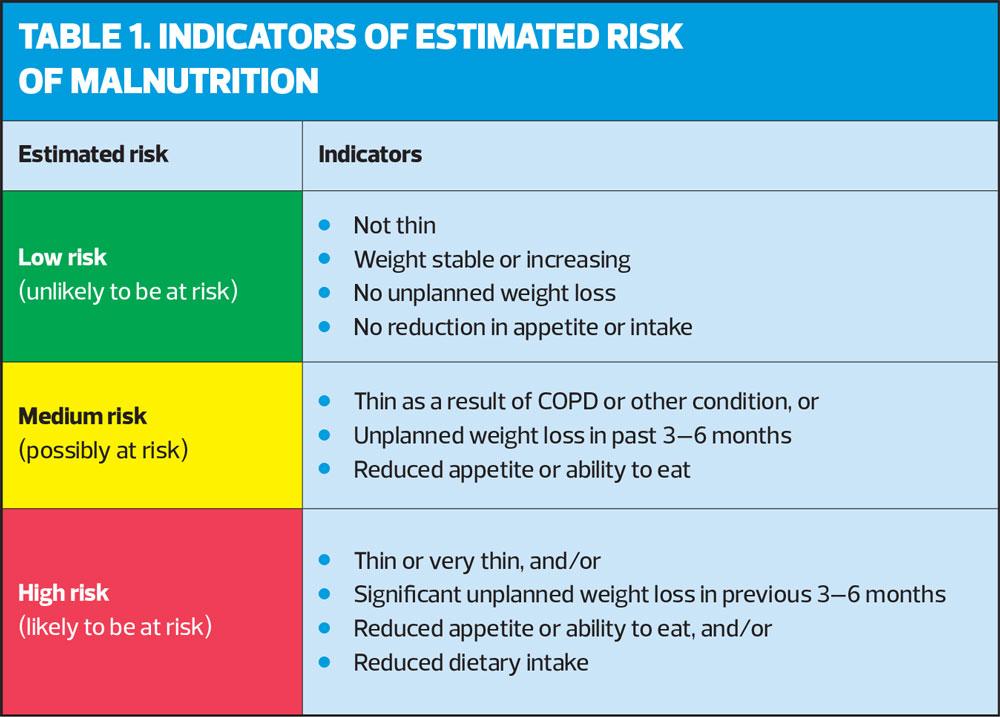

Identifying and managing malnutrition can improve nutritional status, clinical outcomes and reduce healthcare use. NICE guidelines recommend that BMI is calculated in all patients with COPD, and that attention should be paid to unintentional weight loss, particularly in older people.6 However, BMI alone will not identify everyone at risk of malnutrition as a high BMI can mask unintentional weight loss. In addition to considering weight loss of more than 3kg, as recommended by NICE, bear in mind the context of the individual patient’s original weight – 3kg weight loss in someone weighing 45kg is a very different story than in someone weighing 100kg.

Routine screening, using a validated screening tool, should be carried out on first contact with the patient, at times when there is cause for clinical concern, for example, following an exacerbation, or if there is a change in the patient’s social circumstances or psychological status, before and after pulmonary rehabilitation, or at the very least, at the annual review.1

The recommended tool is the Malnutrition Universal Screening Tool (MUST),7 available at www.bapen.org.uk/pdfs/must/must_full.pdf. This combines assessment of BMI, recent unplanned weight loss and presence of acute illness. Unintentional weight loss of 5–10% over 3–6 months indicates malnutrition, irrespective of BMI.7

In the absence of recorded or recalled height and weight, consider:

- Thin or very thin in appearance, or loose fitting clothes/jewellery

- History of recent unplanned weight loss

- Changes in appetite, need for assistance with feeding, or swallowing difficulties affecting ability to eat and drink

- Reduction in current dietary intake compared with ‘normal’ for the individual patient.7

Indicators of estimated risk are shown in Table 1.

Weight loss may also be a sign of other conditions, such as malignancy, and these should be considered and excluded before assuming that the weight loss is COPD-related. Nutritional advice can, however, be offered and should not be delayed while waiting for further investigations.1

MANAGEMENT OF MALNUTRITION IN COPD

Before initiating any intervention to ameliorate malnutrition in patients with COPD, you should record their risk status, agree the goals of intervention, and arrange for regular review to monitor progress.

Goals might include an increase in lean body mass, improvement in nutritional status, and/or to improve respiratory function, stabilise weight, and retain function. Goals should be adjusted according to the patient’s condition, and be realistic – for example, in palliative care or advanced illness, slowing the rate of weight loss may be more appropriate than looking for weight gain.1

Management options include dietary advice, assistance with eating, texture modified diets and oral nutritional supplements (ONS) where indicated.

Dietary advice should aim to increase the intake of all nutrients, including calories, protein, and vitamins and minerals.

Energy and protein requirements are likely to be higher for patients who are:

- At risk, moderately or severely malnourished

- Acutely unwell or who have an infection

- Exercising where the aim is to improve muscle mass.1

The amount of protein recommended in people with COPD is estimated to be between 0.8g and 1.5g per kilo of body weight per day, depending on the patient’s risk status or circumstances. The protein requirements for patients who have had an exacerbation or are acutely ill are likely to be at the higher end of this scale. As a rough guide, patients should be encouraged to eat 3–4 portions of high protein foods per day. A list of the protein content of common foodstuffs is available at: https://www.malnutritionpathway.co.uk/library/protein.pdf.1

Think about any issues that could affect food intake, and the practicalities of dietary advice, such as access to food, reduced mobility and breathlessness.

And unsurprisingly, smoking cessation – if your patient with COPD still smokes – is an important strategy to support the management of malnutrition: not only will smoking cessation help to preserve lung function, but it can also improve appetite and the patient’s senses of smell and taste.1

Patients with COPD who have frequent courses of oral corticosteroids, who are inactive and/or have little exposure to sunlight because they are housebound, for example, are at increased risk of osteoporosis. They may therefore require Vitamin D and calcium supplementation.8,9

ORAL NUTRITIONAL SUPPLEMENTS (ONS)

ONS are indicated in patients with low BMI (<20 kg/m2) or in high risk patients – those who have unintentional weight loss >10% over 3–6 months. They are formulated to increase total nutrient intake (calories, protein and micronutrients).7 In COPD patients with breathlessness, higher energy ONS (≥2 kcal/ml) or low volume, high energy ONS may be easier for them to consume. Frequent, small quantities of ONS taken between meals can help to avoid postprandial dyspnoea.1

The aim of ONS should be to provide around 600 kcal/day but the exact choice should be based on a detailed nutritional assessment and the individual patient’s preference. Clinical benefits are often seen with 300–900 kcal/day, typically within 2–3 months, and include improvements in:

- Respiratory muscle strength

- Exercise performance

- Weight.

- Quality of life.1

Note, your local prescribing guidelines may recommend a ‘food first’ approach before initiating ONS. This involves three small, nourishing meals and two or three additional snacks during the day. Full fat milk can be fortified by adding 4 heaped tablespoons of dried milk powder to 1 pint of full fat milk. Add or increase amounts of high-energy foods, such as full fat milk, cheese, butter, cream and/or sugar to maximise calorie and protein intake.10

However, a 'food first' message is inappropriate for severe COPD patients because breathlessness and hyperinflated lungs make it difficult to eat. Low volume, high protein products are therefore the products of choice so clinicians should be aware of this before they blindly follow local guidelines, which are generally based on cost.

Local guidelines may also have restrictions in place regarding the criteria for initiating ONS, the brand(s) of ONS that can be prescribed, and repeat prescribing of starter packs – some contain a shaker and fewer sachets, making them more expensive, and those with a variety of products should be avoided: instead a specific product should be prescribed based on clinical and cost effectiveness. However, initial prescribing of a starter pack is recommended to avoid wastage, in case products are not well tolerated, and use of free mail order starter packs is encouraged, where practical, to determine which products the patient prefers.10

Some local guidelines also warn that once started, ONS can be difficult to stop, particularly if they are used to replace meals, rather than supplement normal diet, in which circumstance they are of limited clinical benefit.10

Monitor adherence to ONS after 4 weeks, and change the type and/or flavour if necessary to maximise nutritional intake. Assess progress and review goals after 12 weeks (and every 3 months thereafter, or sooner if there is clinical concern): consider weight change, strength, physical appearance, appetite and ability to perform daily activities.1

If goals are met, or good progress has been made, continue to encourage oral intake and provide dietary advice, and consider reducing to 1 ONS per day for 2 weeks before stopping.1

If goals are not met, or progress is limited, check adherence and amend prescription as necessary, reassess clinical condition and refer to a specialist dietitian for more intensive nutrition support.1

Stopping ONS

Consider stopping the ONS prescription if:

- Goals of intervention have been met and the individual is no longer at risk of malnutrition. Reinforce advice on a nutritious diet and the importance of avoiding unintentional weight loss.

- The individual is clinically stable/acute episode has abated.

- The individual is back to an eating and drinking pattern that is meeting nutritional needs.

- If no further clinical input would be appropriate.1

Summary

In our efforts to improve lung function – or at least prevent further deterioration – in our patients with COPD, it is easy to overlook other aspects that contribute to their overall health. Patients who are malnourished simply do not do as well as patients with adequate nutrition. There can be a host of reasons for this, not least that it is difficult to eat for someone who is constantly out of breath. These should be explored, and following a comprehensive assessment, consideration can be given to how to meet the needs of patients with, or at risk of, malnutrition. These guidelines provide a useful foundation for the assessment and management of these patients.

- The production of the ‘Managing Malnutrition in COPD’ materials was made possible by an unrestricted educational grant from Nutricia Advanced Medical Nutrition.

REFERENCES

1. Managing nutrition in COPD. Second edition; January 2020.

https://www.malnutritionpathway.co.uk/library/mm_copd.pdf

2. Hoong JM, Ferguson M, Hukins C, Collins PF. Economic and operational burden associated with malnutrition in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Clinical Nutrition 2017;36(4):1105-1109

3. Steer J, Norman E, Gibson GJ, Bourke SC. P117 Comparison of indices of nutritional status in prediction of in-hospital mortality and early readmission of patients with acute exacerbations of COPD. Thorax 2010;65(Suppl 4):A127

4. Jones SE, Maddocks M, Kon SS, et al. Sarcopenia in COPD: prevalence, clinical correlates and response to pulmonary rehabilitation. Thorax 2015;70(3):213-8

5. Wagner PD. Possible mechanisms underlying the development of cachexia in COPD. Eur Respir J 2008;31:492-501

6. NICE NG115. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in over 16s: diagnosis and management; 2018. https://www.nice.org.uk/ng115

7. Elia M. (Ed). The “MUST” report. Nutritional screening for adults: a multidisciplinary responsibility. BAPEN. www.bapen.org.uk/pdfs/must/must_full.pdf

8. Schols AM, Ferreira IM, Franssen FM, et al. Nutritional assessment and therapy in COPD: a European Respiratory Society statement. Eur Respir J 2014;44:1504-1520

9. NICE CKS. Osteoporosis – prevention of fragility fractures; 2016. https://cks.nice.org.uk/osteoporosis-prevention-of-fragility-fractures

10. Nottinghamshire Area Prescribing Committee. Guidelines for prescribing oral nutritional supplements in adults. https://www.nottsapc.nhs.uk/media/1111/sip-feeds-full-guideline.pdf

Related articles

View all Articles