The art of the sexual healthcare consultation

VAL McMUNN, MSc RN RM ADM

VAL McMUNN, MSc RN RM ADM

Nurse Prescriber, Certificate in Education. Post Graduate Certificate in sexual health. Independent sexual health trainer

Sexual health consultations can be complex, encompassing a wide range of issues from menstruation, unscheduled bleeding, contraception and pregnancy testing, cytology and sexually transmitted infections. Full, detailed and skilful history, appropriate training, and interpersonal skills are paramount

The term ‘sexual healthcare’ has changed over the last few years. It tends to be used generically to include contraception and sexually transmitted infections and is often widened to include cytology. The term can also encompass breast and testicular health. The prevalence of sexually transmitted infection (STI) and the requirements for appropriate cytology screening need to be borne in mind and methods of contraception have become more varied. Sexual health consultations therefore need to include a full and detailed history, which needs to be reviewed at each visit, and consultations have become more diverse and complex.

Collecting information and taking a history from a patient is vital, but its complexity, and the time these consultations can take, should not be underestimated. Patients who seek care in sexual health, in any setting, expect holistic care in a ‘one stop’ visit and are looking for far more complex care than they did 10 years ago.1 The information that is required of them can be potentially embarrassing, forgotten, incorrect, detrimental, surprising, and, depending on the patient, given concisely, or in a confused, accusatory, heart broken, distraught or angry way. You, as the health professional, will need to use all your interpersonal skills to help the patient give the information required in a cohesive, logical and comprehensive way which can then be documented.

Consultations with young people, without parental knowledge or consent, raise further issues. Gillick competence is the legal term for the assessment of young people under the age of 16, to determine if they are able to give consent to care. It is used by the Courts as well as by health professionals.2 However, the terms Gillick competency and Fraser competency are often used interchangeably and although requests for clarification and consistency of use have been requested,3 confusion still prevails. (See Activity 1)

Further confusion can arise when these terminologies are used inappropriately to assess risk in relation to the behaviour of young people under 18, the impact on their health and the need for safeguarding. Young people who are vulnerable will need an assessment of their circumstances at each visit to ensure their safety is not compromised. The review will need to explore any changes in circumstance, risky behaviour, grooming and inappropriate relationships, and abuse.

It is acknowledged that you will need training in several fields if you are to give holistic care and fulfil the patient’s expectations. This article focuses on one aspect of care, bleeding, and its significance to contraception, sexually transmitted infection and cytology.

TAKING A HISTORY

General points

History taking, in relation to the use of language, body language and tone of voice, as well as record keeping, has been well researched and disseminated.3,4 Good communication is linked to patient satisfaction and adherence to advice and/or treatment, while poor communication is linked to misunderstanding and misinterpretation, with negative impacts on care and safety.5,6

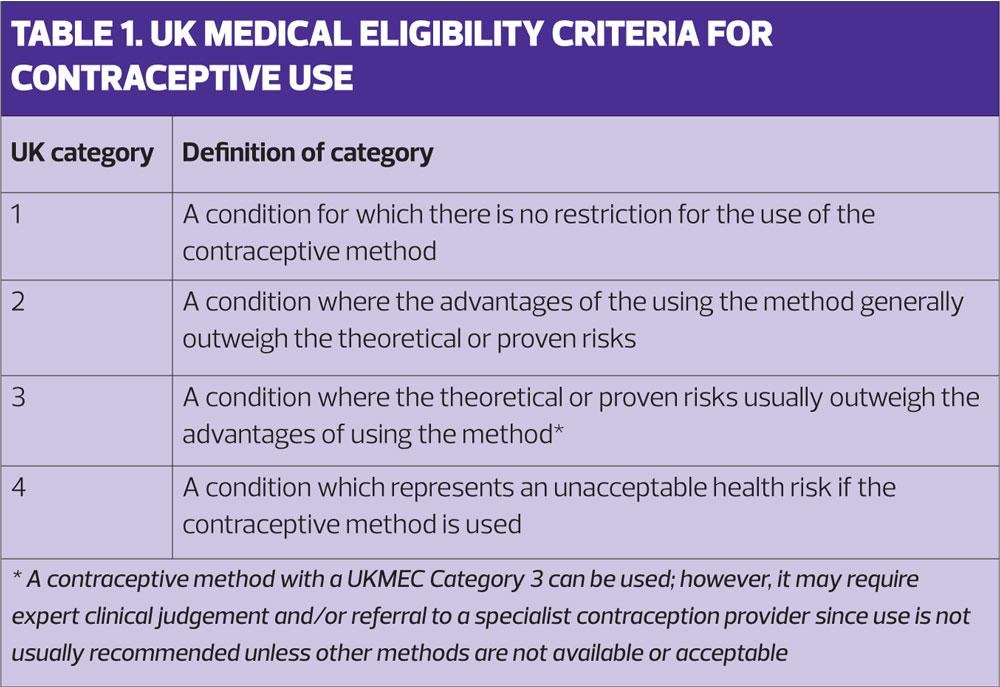

UK Medical Eligibility Criteria for Contraception (UKMEC) 2016

This guidance from the Faculty of Sexual and Reproductive Healthcare (FSRH) covers the assessment of risk in relation to health issues and each method of contraception.7 It aims to aid the delivery of safe care. Table 1 shows the UKMEC categorisation. The full guidance can be accessed at https://www.fsrh.org.

MENSTRUATION

The majority of women have regular menstrual periods (menses) lasting approximately 5 days, with a blood loss that falls into a pattern that is normal for them.

Any contraception method that is commenced on day 1-5 of the menstrual cycle gives contraception cover immediately.

Menarche

The onset of menstruation (menarche) generally occurs when a girl reaches a weight of approximately 51Kg (8 stone). Girls with a higher BMI will generally reach menarche at a younger age. In one study this was at 12.5 years compared with 13.7 years in underweight girls.8

Early menses may be heavy, unpredictable and painful.9 The combined oral contraceptive pill (COC) can reduce these symptoms, especially if an extended regime is used.10 However, the COC is not licensed solely for the treatment of dysmenorrhea in young girls, but is a good method if they are sexually active.

The combined pill can be commenced from the age of menarche to the age of 50 providing all the UKMEC criteria are met.7

Disruption of menses

When taking a history one of the first questions to be asked is ‘When was the first day of your last period?’, and ‘Was this period normal?’. Any woman who has unexplained or unscheduled bleeding warrants investigation before starting a method of contraception. This is a UKMEC category 3 for the initiation of a contraception method in most cases.7

A woman who has not had her regular menses may already be pregnant and needs a pregnancy test prior to starting contraception. If, however, oral contraception has inadvertently been taken during early pregnancy no significant harm has been found to the fetus,11 but this can be avoided by good history taking.

There are several reasons, other than pregnancy, for disruption of a woman’s regular menses. It may be due to a progesterone method of contraception, such as the progesterone only pill (POP), implant, intrauterine system (IUS) and medroxyprogesterone acetate (MDPA) injectables e.g. Depot Provera and Sanya Press. Disruption of menses is a usual side effect with progesterone methods and it is important to forewarn a woman about the possible effect on menses as this is the most common reason why women stop using the method. With the use of MDPA and IUS it is usual that menses cease over time. This can also happen with the implant and POP but is less likely.

Irregular menses and abnormal vaginal bleeding may, however, have a pathological cause, such as polycystic ovary, cancer of the cervix (especially if the woman is not up to date with screening), endometriosis and endometrial cancer, polyps and fibroids. This would require the patient’s history to be to explored further and an appropriate referral made.

Irregular menses can also have less sinister but equally important causes. Disruption of menses may be related to higher BMI, smoking, and high alcohol intake. 12,13 Alcohol intake in particular should be reviewed at each visit, not just as a health promotion opportunity but also to assess the chance of pills being vomited within 3 hours of ingestion. This would cause a ‘missed pill’ scenario, putting the woman at risk of pregnancy and possibly causing unscheduled bleeding.

Any missed pills can potentially put a woman at risk of pregnancy but more so if they are missed at the beginning or end of the pack. It is important to review whether the woman is taking the pill appropriately at each visit: is pill taking part of her daily routine? Does she ever forget and what does she do if she has forgotten? To reduce bleeding and the risk of pregnancy, extended taking of COC – by either taking two or three packs with no pill free interval or reducing the pill free interval to 4 days – is now a recognised option.14,15

In summary, while some methods of contraception can cause cessation of menses, pregnancy should be excluded if compliance with a contraception method is uncertain. No method of contraception should be commenced or continued, or cytology offered, until the risk of pregnancy has been assessed. In addition, some treatments for sexually transmitted infection (STI) are contraindicated in pregnancy.

Menopause

Women starting the menopause may experience heavy, painful and erratic menses. The IUS can be offered for heavy menstrual bleeding,16 and is licensed for peri-menopausal treatment of menorrhagia.17 It can also be used as the progesterone element in hormone replacement therapy (HRT).17 An IUS can also reduce symptoms related to endometriosis, such as bleeding and pain.18

PREGNANCY TESTING

A pregnancy test (PT) is not just a case of putting a few drops of urine into a proprietory device and waiting for the test to become positive. It is when to conduct the PT in relation to menses that is important.

The first accurate time a PT can be taken is if a woman is 2 days late from her last period (i.e. 30 days since first day of last menses) or 21 days from the first episode of unprotected sexual intercourse (UPSI). The guidance takes into account the level of human chorionic gonadotrophin (HCG) required to give an accurate PT result. If the test is done earlier not enough HCG has been produced to give an accurate result, giving a false negative result.

Knowing the date of UPSI is helpful if a woman does not know when her last period was i.e. if she does not remember or has been using a method of contraception that has caused her not to bleed for some time.

If the test has been taken at the right time, is negative and the woman does not want to be pregnant, quick starting a method of contraception is acceptable, and combined with condom use for 7 days prevents further risk of pregnancy, and is seen as best practice. The contraceptive method mostly used for quick starting is the POP as this prevents pregnancy within 2 days.

If the test cannot be taken at the appropriate time the woman will need to be reviewed. The timing of that review will depend on the history in relation to last UPSI and should be no less than 21 days from that episode. If, at that time, the pregnancy test is negative or she has started her menses and there is no further risk of pregnancy any method of contraception can be used, depending on her choice.

If the PT is positive, the woman can be referred for midwifery care or be counselled and referred for a termination of pregnancy, depending on her choice. In the latter scenario the consultation should include future contraception use.

DRUGS

Another vital part of a sexual health consultation is to ask about other medication use, either prescribed and over the counter (OTC).

The potential for unwanted pregnancy and unscheduled bleeding is more likely to occur when liver enzyme-inducing drugs, which prevent normal metabolism of hormones, are taken. Among these is St John’s wort, a popular, alternative, OTC therapy used for low mood.

Stockley’s Drug Interactions is the most relevant and accurate drug interaction resource for the UK population and is recommended by the FSRH.19 Most NHS healthcare professionals can get free access to Stockley’s using an Open Athens login. (See Activity 2) The FRSH has also issued guidance on which methods of contraception are reliable for women taking liver enzyme-inducing drugs. (Table 2)

INFECTION

Women, who complain of unscheduled bleeding, or bleeding after sex, should be routinely tested for chlamydia. In 2016, 128,000 Chlamydia diagnoses were made in young people aged 15 to 24 years, and the positivity rate was about 9–10% of all tests taken.20 Depending on the history and symptoms, a full sexual screening may be required, in which case the patient should be referred to a Genitourinary Medicine clinic.

CERVICAL CYTOLOGY

Cervical cytology is a screening tool. Samples should only be taken at the request of the screening programme, or opportunistically in the event of a woman being late for, or not attending for a scheduled smear. If a woman has irregular bleeding cervical cytology should not be taken for the purpose of diagnosing a suspected abnormality.

Cervical smears should not be taken during menstruation. At this time it is more difficult to visualise the cervix and a blood stained sample is more difficult for the laboratory to process. Endometrial cells, lost during menses, can look like dyskariotic cells, making reporting more difficult and a false positive result more likely. However, the sample can be taken at any other time during a cycle.

Cervical cytology should not be performed if the woman is pregnant and should be deferred until she is 12 weeks post partum. The reasons for this are:21

- The transformation zone is wider due to growth of the cervix and the cytology brush may not pick up all the cells needed for an accurate report

- There is often a larger ectropion that may bleed heavily during or after the procedure, making the sample more difficult for the lab to process and more distressing for the woman

- The use of the brush in the os may stimulate contractions or cause discomfort

- If an abnormality is found, colposcopy is usually deferred until after delivery, causing increased distress and anxiety for the patient

- Any dyskariotic abnormality will not develop at an increased rate because the woman is pregnant so deferring the examination will not put her at increased risk.

If a woman has abnormal or unscheduled bleeding and is either too young to be screened (<24.5 years) and has not been called, or is up to date with her cervical screening, other reasons for the bleeding need to be explored, some of which are not related to the cervix. The following list covers the main issues but is not exhaustive:

- Failure to take OC as prescribed – the ‘missed pill’ scenario

- The woman has just started a new method of contraception

- She is taking other drugs, such as liver enzyme inducing medication or St John’s wort, which may interact with OC. Weight loss medication bought from the Internet may have made her vomit, affected her metabolism or given her diarrhoea

- Binge drinking may cause her to vomit her oral contraception – another cause of the ‘missed pill’ scenario

- She may have a sexually transmitted infection. (Chlamydia screening would be advised as routine for any young girl complaining of unscheduled bleeding)

- The use of sex toys, or participating in ‘rough’ sex may cause vaginal bleeding.

In these scenarios education and information to make the woman aware of the cause and how to prevent it is all that is needed. However, if the bleeding is not related to simple issues and is more complex, e.g. polycystic ovary syndrome, endometriosis, pelvic inflammatory disease, endometrial/ovarian cancer, further investigation and appropriate referral is required.

If bleeding is thought to be related to the cervix, cervical cytology should not be performed but the cervix should be examined for abnormality. Bleeding may be related to a large ectropion, polyps, or fibroids and the woman should be referred appropriately. If, however, the cervix looks abnormal the woman should be fast tracked for assessment and treatment within the 2 weeks guideline.

CONCLUSION

Giving sexual healthcare to women is often complex and many issues may arise. However, the importance of bleeding cannot be underestimated.

For each consultation, appropriate training will be necessary as well as sufficient time to take a full history. Awareness of the possible causes of unscheduled bleeding and the treatment required is essential so that safe and appropriate care can be given.

REFERENCES

1. Gott M, Galena E, Hinchcliff S, Elford H. Opening a can of worms: GP and practice nurse barriers to talking about sexual health in primary care. Family Practice 2004; 21(5): 528-536 https://doi.org/10.1093/fampra/cmh509

2. Griffith R. What is Gillick Competence? Hum Vaccin Immunother 2016; 12(1): 224-247

3. Fast J. Body language. How our movement and posture reveal our secret selves. 2014. Open Road Media ISBN 1497622689

4. Kourkoutal L Papathanasiou (2014) Communication in nursing practice. Materia socio- medica 2014; 26(1): 65-67 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3990376/

5. Corcoran N. Communicating health: strategies for health promotion. 2nd edition. Sage. London 2013 ISBN 978-1-4462-5232-1

6. Likupe G. Communicating with older ethnic minority patients, Nursing Standard 2014; 28 (40): 37-43

7. Faculty of Sexual and Reproductive Healthcare (FSRH) UK Medical Eligibility Criteria for contraceptive use: UKMEC 2016 https://www.fsrh.org/standards-and-guidance/external/ukmec-2016-digital-version/

8. Bau A, Ernert A, Schenk L, et al. Is there a further acceleration in the age at onset of menarche? A cross-sectional study in 1840 school children focusing on age and bodyweight at the onset of menarche. Eur J Endocrinol 2009;160:107-113 http://www.eje-online.org/content/160/1/107.long

9. Jamieson M. Disorders of menstruation in adolescent girls. Pediatric Clinics 2015; 62(4): 943-961

10. Nappi R, Kaunitz, Bitzer J. Extended regimen combined oral contraception: A review of evolving concepts and acceptance by women and clinicians. The European Journal of Contraception and Reproductive Health Care. 2015; 21(2): 106-115 https://doi.org/10.3109/13625187.2015.1107894

11. Charlton BM, Molgaard-Nielsen D, Svantrom H et al. Maternal use of oral contraceptives and risk of birth defects in Denmark: prospective, nationwide cohort study. BMJ 2016; 352: h6712

12. Jung An Na, Park Ju Hwan, Kim Jihyun, et al. Detrimental effects of higher body mass index and smoking habits on menstrual cycles in Korean women. J Womens Health 2017: 26(1): 83 – 90 https://doi.org/10.1089/jwh.2015.5634

13. Rachdaoui N, Sarkar D. Pathophysiology of the effects of alcohol abuse on the endocrine system. Alcohol Res 2017; 38(2): 255–276. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5513689/

14. Millar L, Hughes J. Continuous combined contraceptive pills to eliminate withdrawal bleeding: RCT. Obstet Gynecol 2003; 101: 653-661

15. FSRH Clinical Effectiveness Unit. Combined Hormonal Contraception, 2012 https://www.fsrh.org/standards-and-guidance/documents/combined-hormonal-contraception/

16. Lethaby A, Hussain M, Rishworth J, et al. Progesterone or progestogen-releasing intrauterine systems for heavy menstrual bleeding. Cochrane Database system review 2015;4:CD002126 http://cochranelibrary-wiley.com/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD002126.pub3/full

17. FSRH Clinical Effectiveness Unit. Clinical guidance: Intrauterine Contraception,2015 https://www.fsrh.org/standards-and-guidance/documents/ceuguidanceintrauterinecontraception/

18. Lockhart F. The effect of levonorgestrel intrauterine systems (LNG-IUS) on symptomatic endometriosis. Fertility and Sterility 2002; 77: 485-488

19. FSRH. Clinical guidance: Drug interactions with hormonal contraception, 2017. https://www.fsrh.org/documents/ceu-clinical-guidance-drug-interactions-with-hormonal/

20. Public Health England. Sexually Transmitted Infections and Chlamydia Screening in England, 2016. Health Protection Report 2016; 11(20)

21. NHS Cancer Screening Programme. Guidance for the training of cervical sample takers. November 2016

Related articles

View all Articles