Spotlight on confidentiality

Beverley Bostock

Beverley Bostock

RGN MSc MA QN

ANP Mann Cottage Surgery, Moreton in Marsh

PCN Nurse Coordinator, Hereford

Practice Nurse 2022;52(1):28-31

As a healthcare professional you have of access to, and knowledge of many intimate and personal details of your patients’ lives. There are rules about how this confidential information is used, and when, why and to whom it can legitimately be disclosed

As a healthcare professional you have of access to, and knowledge of many intimate and personal details of your patients’ lives. There are rules about how this confidential information is used, and when, why and to whom it can legitimately be disclosed

One of the great pleasures of working in general practice is the in-depth knowledge and familiarity general practices nurses (GPNs) develop with their patients. Many GPNs will have seen babies that they immunised years ago having babies of their own, and their parents becoming grandparents. Life experiences change, people suffer and recover from a range of complaints, some develop long term conditions and become frequent attenders for care and support. General practice offers us the unique experience of seeing life moving on for the individuals and families with whom we are involved.

General practice is sometimes referred to as ‘family medicine’ and it is easy to see why. It’s not unusual for a GPN to work at the same practice for decades and become professionally involved with the people who come through their door – we know so much of their joys, successes, trials and tribulations. However, intimate knowledge of people, their families and their lives is a privilege and should never be taken for granted.

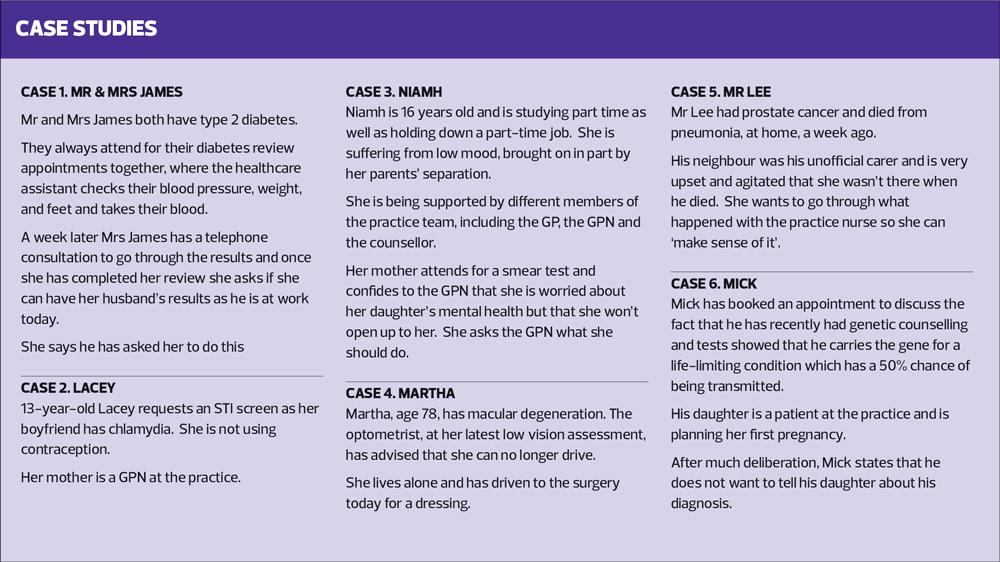

In this article we shine a spotlight on the importance of respecting confidentiality in general practice by presenting some scenarios which could occur in day-to-day practice and which might give some pause for thought. Before reading further, consider the situations described in Cases 1–6. Do they pose any confidentiality issues that need to be addressed?

DEFINITION: WHAT IS CONFIDENTIALITY?

In healthcare, confidentiality means respecting someone’s right to privacy by keeping all information held about them safely and securely, and only sharing information with people who need to know.1 Everyone, including children and the dead, have a right to confidentiality unless there is an overriding reason why that right should be breached. Legal Acts which help to define confidentiality include the Care Act, the Health and Social Care Act and acts relating to data protection and the General Data Protection Regulation.2

In general, the reasons for breaching confidentiality involve the risk of harm from that breach being less than the risk of harm from withholding information.2 The risk of harm may be to the individual, to another person or to the greater good and must be such that refusing to disclose information would cause such harm.

Most patients understand that confidential information will be shared with other healthcare professionals, for example when they are referred to see a specialist or another member of the multidisciplinary team. However, practices are now advised to ask for and document consent in the records. In the case of Mr and Mrs James (Case 1), it may well be that they have a documented agreement on the practice computer stating that they can:

- Make and cancel appointments for each other

- Order prescriptions, and

- Share other information with each other.

However, it is still worth checking that this continues to be the case. Ideally this would have been revisited and reconfirmed on the day of the first appointment, when they attended together for their blood tests. This could then be documented afresh, making it clear that the blanket agreement still held firm, for this appointment and the follow-up. If all this had been addressed and noted on the records, Mr James’s results could be communicated to Mrs James. However, it might still be better to have a direct conversation with him to ensure he has ‘ownership’ of his diabetes and understands the role he has to play in self-managing.

RESPECTING CONFIDENTIALITY – CALDICOTT AND BEYOND

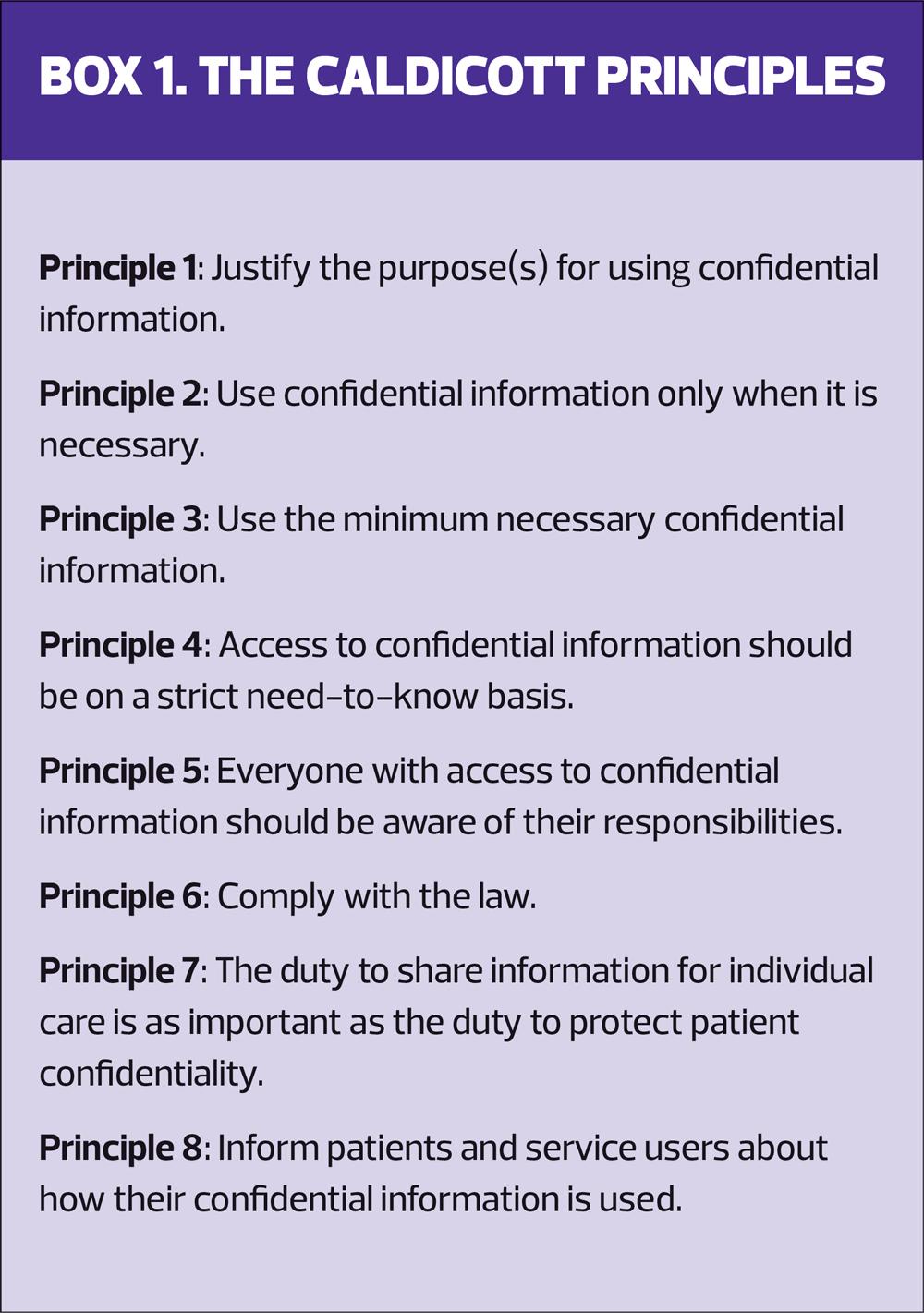

In 1997 a review, chaired by Dame Fiona Caldicott, was commissioned to look into the use of patient information, and the ability of the increasing use of information technology in the NHS to disseminate patient information rapidly and extensively. This committee published its report, ‘Report on the Review of Patient-Identifiable Information’, usually referred to as the ‘Caldicott Report’, in December 1997 and came up with eight ‘principles’. (Box 1) These ‘Caldicott Principles’ were developed to explain how, when and why confidential information should be handled correctly in a healthcare setting.3 (See Activity 1)

In summary, the principles state that all use and transfer of confidential information should be justified through careful scrutiny and documentation, and ongoing use should be regularly reviewed by the assigned Caldicott guardian. Confidential information should only be shared when necessary and the need to share detailed information (e.g. names) should be justified so that only the minimum amount of confidential information is included in each separate situation. As every healthcare worker will have access to confidential information, each individual should be aware of their ethical, moral and legal responsibility to respect patient confidentiality.

However, the recent case of Arthur Labinjo-Hughes acts as a stark reminder of the importance, at times, of sharing information when this in the best interests of patients; specifically when the care of an individual is more important than the duty to protect patient confidentiality. In this respect, it is essential that healthcare workers are supported by the policies of their employers, regulators and professional bodies.

The Caldicott Principles remind us that patients should be informed about how their confidential information is used, so that they can have clear expectations and understand the choices they have with respect to the sharing of these data. This can be achieved at a basic level by providing accessible, relevant and appropriate information for people about these areas.3

The Nursing and Midwifery Council has produced guidance which echoes that of the Caldicott Principles.4 It has also published a guide to using social media responsibly, which includes reference to confidentiality.5 Nurses should also be aware of the requirements of the code of conduct with respect to observing confidentiality in all situations.

CHILDREN AND CONFIDENTIALITY

Children have the same right to confidentiality as adults and this aligns, to an extent, with their capacity to consent to treatment. Capacity means that they have the ability to comprehend the information needed in order for them to make a decision to consent to medical treatment, and they can use and weigh up that information when deciding. Competence is a person’s ability to make and communicate their decision to consent to medical treatment. Capacity is.automatically assumed from the age of 16, but competence can also be assessed via the Gillick or Fraser competency test in younger children.6 If a young person is competent then they also have capacity and they should expect to have their confidence respected.

It can be difficult to define the border between confidentiality for children and respect for parental responsibility, and there are no hard and fast rules on this – each case will be decided on its own merits and after discussion with either or both parties. In most cases, children are happy to have parents involved in their care, but this should not be assumed. In reviews of long-term conditions, it may actually be preferable for the child to be seen alone to discuss issues around smoking, lifestyle choices and self-management, and many parents will value this approach.7

In Lacey’s case (Case 2) there are important decisions to make. It is good to know that she feels able to come to the practice to be tested for chlamydia and other infections and this underlines one of the key principles of why confidentiality rules exist – to allow the free flow of information between patient and clinician in order to facilitate the diagnosis and management of any condition.

If she is competent, Lacey has every right to access the healthcare she needs in confidence. However, any situation where a child attends alone for a consultation should require the clinician to consider the reasons for this. In Lacey’s situation, why she is attending alone might seem to be obvious, but she should still be encouraged to discuss her situation with a parent or other adult.

She may, however, also be the subject of an abusive relationship so understanding more about this relationship, including the age of her partner and whether she is in any sort of coercive situation should be determined. The parameters around disclosure should be explained so Lacey understands that there may be a need to share information more widely if her situation demands it. Her situation also has the potential to be a safeguarding issue as she has been putting herself at risk of sexually transmitted infections and an unwanted pregnancy at 13. Is alcohol a factor, or drugs? Is there any suggestion of trafficking or sexual abuse? In view of her age, the consultation has to be carried out with gentle respect but with awareness of the possible implications for all parties.

Lacey’s case also highlights the reason why healthcare staff are asked to avoid having relatives under their care. The fact that her mother is a GPN at the practice means that there is an increased risk of a breach of confidentiality, either by conversations between colleagues or via the mother accessing her daughter’s records. A breach of confidentiality such as this could result in a Fitness to Practise hearing with the Nursing and Midwifery Council and loss of the mother’s registration.

WHEN CAN YOU BREACH CONFIDENTIALITY?

The Caldicott Principles clearly state that confidentiality can be breached when the sharing of information would be in the best interests of the patient or others. This might be because the patient is at risk of harm or because others may be harmed if information is not shared. There is clearly a potential conflict between confidentiality and safeguarding, irrespective of the age of the patients involved, and it is important that GPNs are aware of when they should breach confidentiality.

Concerns around mental health in young adults, such as Niamh (Case 3), has meant that universities have recently been advised that they can inform the parents of a student if there are significant concerns about their mental health. At 16, Niamh is assumed to have capacity to consent to treatment and has a right to expect her privacy and confidentiality to be respected by the healthcare professionals involved in her care. Despite the fact that she lives with her mother, and the fact that her mother has expressed her concerns, the professionals involved should not breach Niamh’s confidentiality or disclose any information to her mother unless Niamh is thought to be at risk of harming herself or others.

In law, things are rarely, if ever, black and white and any disclosure, no matter how good the GPN’s intention, risks legal action. In reality, each case would be assessed on its merits, but there needs to be clear evidence of the necessity of breaching confidentiality if this has occurred.

This is important with regard to Martha and her macular degeneration (Case 4 ). If Martha is aware of the advice she has been given about driving (and it would be important to check that she has understood this) then the GPN has a duty to report her to the DVLA in order to protect other road users. The GPN should also inform Martha that she is required to do this.

In the case of Mr Lee (Case 5), whose neighbour wishes to know more about the circumstances of his death, the duty of confidentiality remains after death, so the neighbour has no right to ask for this information. However, if the neighbour then went to the police and the courts require access to the medical records, the practice must make these available or potentially be accused of contempt.

In Mick’s case (Case 6), a breach of confidentiality is allowed because he fulfils three key principles:

- He refuses to inform his daughter

- There is a serious risk of harm to her and her unborn child, and

- This potential harm can be prevented by disclosure.

This situation has previously been tested in court and went to appeal because there are different perspectives, rights and confidences which all have to be balanced. In the end, however, the court’s decision was that information should be shared with relatives even if sharing it breaches confidentiality. Similar rulings have been made with respect to sexually transmitted infections.8

SUMMARY

Confidentiality is essential in healthcare if there are to be free and frank exchanges of information from the patient to the clinician. As a result, the law and the relevant professional bodies have produced guidance on how to respect confidentiality and, importantly, when confidentiality can be legitimately breached.

Every case should be assessed individually before deciding whether to respect confidentiality (the default position) or breach it (in specific and unusual circumstances), especially when dealing with vulnerable groups, such as children.

REFERENCES

1. Bourke J, Wessely S. Confidentiality. BMJ 2008;336(7649):888–891. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.39521.357731.BE

2. NHS Digital. A Guide to Confidentiality in Health and Social Care; 2021 https://digital.nhs.uk/data-and-information/looking-after-information/data-security-and-information-governance/codes-of-practice-for-handling-information-in-health-and-care/a-guide-to-confidentiality-in-health-and-social-care

3. National Data Guardian for health and social care. The Eight Caldicott Principles; 2020 https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/942217/Eight_Caldicott_Principles_08.12.20.pdf

4. Nursing and Midwifery Council. The Code; 2018 https://www.nmc.org.uk/globalassets/sitedocuments/nmc-publications/nmc-code.pdf

5. Nursing and Midwifery Council. Guidance on using social media responsibly; 2019. https://www.nmc.org.uk/globalassets/sitedocuments/nmc-publications/social-media-guidance.pdf

6. NHS. Children and young people – Consent to treatment; 2019 https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/consent-to-treatment/children/

7. BTS/SIGN. BTS/SIGN British Guideline on the Management of Asthma; 2019. https://www.brit-thoracic.org.uk/quality-improvement/guidelines/asthma/

8. Lucassen A, Gilbar R. Alerting relatives about heritable risks: the limits of confidentiality. BMJ 2018;361:k1409. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.k1409

Related articles

View all Articles