Embedding group consultations into practice: Perceptions of the general practice workforce

Eleanor Scott

Eleanor Scott

RN, BSc (Hons), MSc

PhD student[1]

Dr Laura Swaithes

BSc (Hons) (Physiotherapy), MA PhD

Knowledge Mobilisation Research Fellow[2]

Dr Gwenllian Wynne-Jones

RN Dip, BSc (Hons) PhD

Director of Research

Reader in Epidemiology and Clinical Trials[1]

Dr Andrew Finney

RN, Dip, BSc (Hons), PhD

Senior Lecturer of Nursing[1]

1. School of Nursing and Midwifery, Keele University

2. School of Medicine, Keele University

Practice Nurse 2021;51(05):12-16

Group consultations are to be ‘championed’ to address growing concerns facing primary care general practice, but what are the barriers, facilitators and key roles required in setting up and delivering this model of care, according to the experiences of healthcare professionals?

The increased drive to enhance service provision has accelerated pressures across the general practice landscape, with the general practice workforce described as at ‘breaking point’.1 The increasing workload over the last decade has not been adequately matched with funding, staff, or time, which has led to staff ‘burnout’ and a recruitment and retention crisis.1 More recently, The NHS Long Term Plan2 has attempted to address these issues, proposing newer ways of delivering care, with increased multidisciplinary working across primary care networks, greater collaboration of services, creation of new job roles to support practice staff and facilitation of new services within primary care.3 One such, relatively new, service is the group consultation.

Group consultations are an alternative approach to deliver care in primary care settings, in particular in general practices, contributing to annual Quality Outcomes Framework (QOF) reports by supporting the management of long-term conditions.4 This has been demonstrated in managing diabetes, chronic pain, hypertension, cancer, menopause, and asthma.5-7 As much of the early work was conducted in the US, there is still relatively little known about group consultations in UK general practice.8,9

In the UK, group consultations feature in the Ten High Impact Actions by the Royal College of General Practitioners (RCGP)10 as part of the NHS England General Practice Development Programme.11 Group consultations have shown to be effective for patients in some regional evaluations, in terms of clinical outcomes and patient satisfaction.12 However, little is known about the views of the workforce about using this approach as an alternative to one-to-one consultations in general practice.

A qualitative study in the British Journal of General Practice by Swaithes and colleagues has explored the experiences of healthcare professionals implementing and delivering group consultations,13 providing a unique contribution to the evidence-base in the UK. The aim of this article is to summarise and discuss the findings of this study, highlighting the advantages of and barriers to the approach, key steps for implementation and recommendations for practice.

ADVANTAGES

Many participants perceived group consultations as having the potential to release capacity, due to views that current models of care are not sustainable. A shift from the traditional medical model to a greater holistic approach to care was favoured, helping to remove the tick-box mentality driven by QOF. Participants felt this model of care promoted a more relaxed approach with extra time, aiding positive patient-clinician relationships, without the ‘monotonous’, ‘isolating’ and ‘hierarchical’ qualities of individual consultations. Many participants felt they could get to really understand what it meant to live with a chronic condition and valued the peer-to-peer support, which challenged patients to think differently about their own condition, especially regarding sensitive issues such as weight management and lifestyle. It also helped clinicians recognise the level of knowledge patients had regarding their condition, which wouldn’t necessarily be shown in an individual consultation, due to the different type of encounter in a group setting.

Group consultations were reported, in some cases, to help improve cohesiveness between teams. The up-skilling of junior clinicians was discussed as a by-product of group consultations, helping to develop a specific skill set for effective facilitation, as well as creating opportunities for leadership roles and presentation skills. Group consultations can therefore be viewed as an educational activity for all healthcare roles, aiding the continued professional development of primary care staff.

However, favourable perceptions of the approach were dependent on a practice’s innate motivation to set up of group consultations to support the management of long-term conditions. Some practices aimed to adopt this approach in the management of other medical conditions, and to help to improve multi-disciplinary working across general practice teams.

BARRIERS

Some participants expressed hesitant experiences, described as barriers to the set-up and delivery group consultations, due to concerns regarding workload and responsibilities, appropriate knowledge and skills to deliver a consultation, or the desire to adopt new roles. Many participants, in particular clinicians, felt they were expected to demonstrate a different skill set in a group environment than in a one-to-one, despite delivering the same consultation in terms of content. This was particularly apparent when other clinicians were part of a group consultation, as many felt anxious regarding their skill set and knowledge base.

A spectrum of engagement was also identified, ranging from ‘passive supporters’, individuals who did not prevent group consultations being set up, but who did not actively engage in their establishmment, to ‘blockers’, those with attitudes and behaviours which could stop the introduction of group consultations. Some practice nurses had the ambition to drive change, but often felt restricted as they were not deemed key decision makers by the practice team, despite having innate positive motivation. Implementation was therefore heavily reliant on the buy-in of senior decision makers. Many participants felt whole practice engagement was regarded as essential to ‘sell’ the approach, which heavily relied on the role of the facilitator to gain support of the practice team to initiate set-up and delivery. The importance of good working relationships and structures were apparent, for instigating change and to champion the approach.

In some instances, group consultations were established through ‘trial and error’, regarding planning and support, role requirements and facilitation. This impacted on the sustainability of group consultations in practice, whereby a reported challenge was the inability to integrate them into everyday practice.

The ‘trial and error’ approach illustrated how it was important to have a clear implementation plan at the beginning, with support of both practice staff and commissioner ‘buy in’, in terms of planning, funding and resources. Those practices which had successfully embedded group consultations believed the extent to which this approach was embedded was limited, due to a lack of time to evaluate implementation. Therefore, a lack of robust evidence on the effectiveness of group consultations in practice has become apparent.

KEY ROLES REQUIRED

Many participants believed the introduction and delivery of group consultations in general practice was dependent on effective facilitation. This was viewed as a facilitator role, or ‘champion’ to organise and run the consultation, with many practices allocating a non-clinical healthcare professional to conduct this role. The ‘champion’ role, more specifically, refers to an individual who adopts a leadership role to influence and drive group consultations in their practice. This role is often viewed as an extension of a previously established role, with the expectation that the facilitator will maintain their ‘day job’ as well as take on additional tasks such as project management, marketing and contractual agreements. Participants reported that the facilitator encountered the largest workload with regards to planning, running and managing the approach, as well as being a ‘champion’ in selling the approach.

A lack of clarity around role definition also can lead to difficulties in recruitment, selection and training of a facilitator, raising questions about how practices allocate a facilitator. The ‘champion’ role demands a specific skill set, such as health coaching or behaviour change techniques. Presentation and leadership skills are also required, in which the facilitator is expected to lead and run the group, as well as managing the group dynamic. However, this role requires health professionals to adopt this skill set without any formal training. Practices may offer in-house training, but due to the responsibilities required of this role, this may not be adequate to encompass all aspects of what it means to be a ‘champion’ of group consultations. The lack of training and support for this critically important role raises questions about the sustainability of the approach.

The need for training is often dependent on the priorities of both the individual practice and the local Clinical Commissioning Groups (CCGs). Many of the participants in this study were able to dedicate time to the introduction and/or delivery of group consultations because they had the support of ‘professional launch pads’ and financial incentives from funding schemes to support the uptake of group consultations, although this still demands the buy-in of the CCG to support set-up and delivery. A lack of flexibility in terms of commissioning support was referred to, alongside a lack of recognition of group consultations with regards to payment systems and clinical coding, which resulted in an inability to sustain this approach. Many participants felt group consultations should be incorporated into the QOF templates, as financial incentives are not always apparent or accessible with the current systems and structures.

DISCUSSION

The changing nature of primary care itself builds a foundation to which group consultations have the potential to be incorporated into everyday practice. This foundation is supported with new roles in primary care such as social prescribers, practice pharmacists and first-contact physiotherapists, which not only enable a multi-disciplinary delivery of care, but also help to foster sharing of knowledge and skill set across other primary care roles.3 Group consultations can therefore provide a platform for healthcare professionals to collaborate, share knowledge and experience, and deliver holistic multi-disciplinary care – a shift away from current models of care used to manage long-term conditions.9,14 However, concerns regarding the key role requirements such as a lack of dedicated job specifications, training, support and mentorship for those facilitating group consultations raises questions about the sustainability of the approach.

Due to the impact of the pandemic, however, the need for newer ways of working has become more apparent. Video consultations are one way to reduce direct clinician-patient contact due to social distancing measures, a shift that can be deemed as both technical and cultural.15 Online platforms can be used for both individual consultations and group consultations. Video is playing an increasingly important role in providing patients with the opportunity to access healthcare by alternative means, and for some, this may be the only means of access. Those with symptoms of COVID-19 or those patients shielding due to other conditions can make use of this virtual platform, and still receive the same standard of care they would have done otherwise.

The potential to deliver group consultations via a video-conferencing platform creates an opportunity for both patients and healthcare professionals to access and deliver these services. However, more evidence is needed to assess the viability of video group consultations as an alternative to a one-to-one approach. The findings of the Swaithes study13 can greatly inform further research on the factors affecting the set-up and delivery of video group consultations, because of the similarities in consultation style. Like group consultations, successful introduction, sustainability and scale-up of both these approaches depends on the presence of innovators, champions and change agents.12,15,16

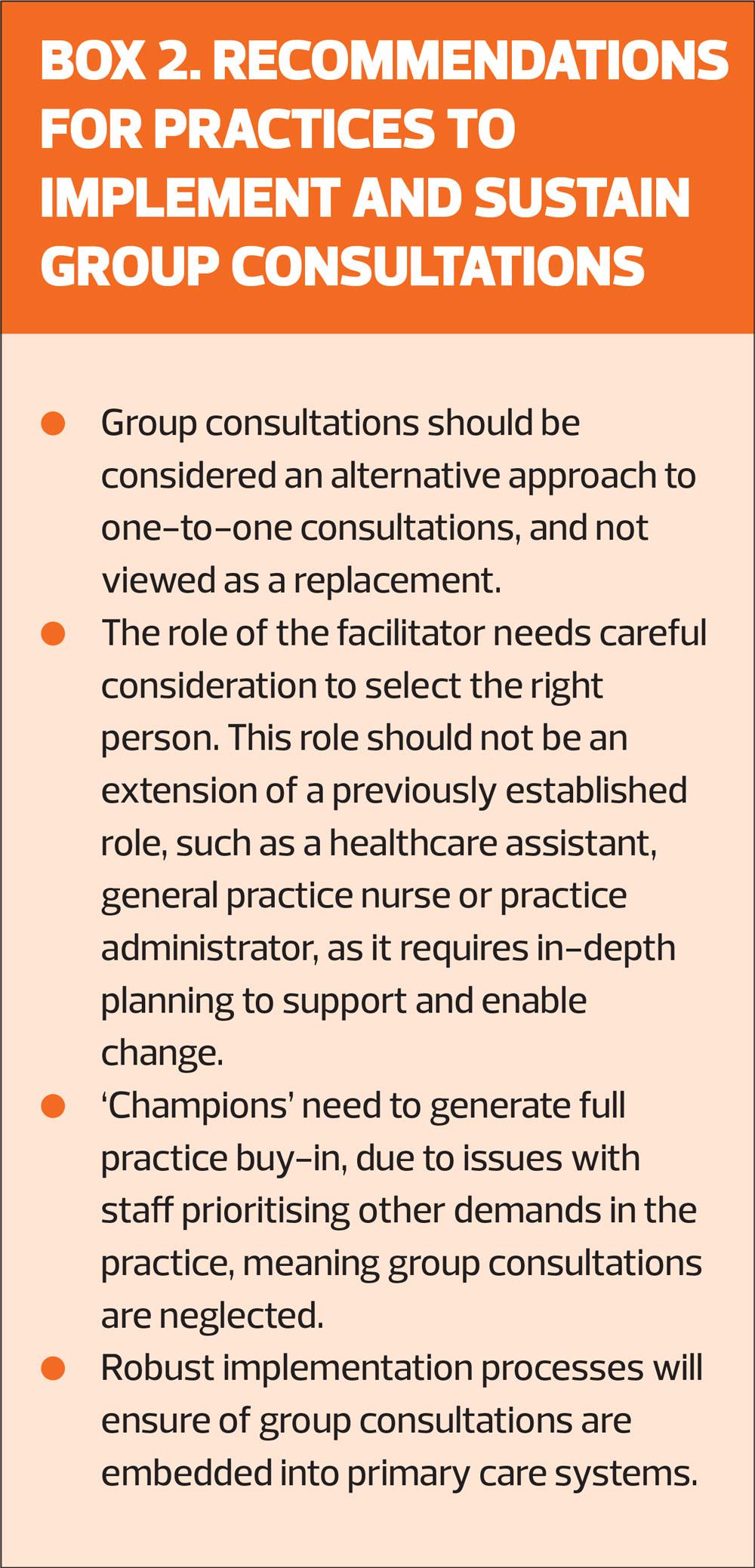

RECOMMENDATIONS

Due to the complexity, diversity and bespoke nature of group consultation models, little is known about how group consultations can be fully embedded or used routinely across UK general practice. A clear implementation plan from the outset is therefore essential to enable the sustainability of group consultations in primary care general practice. Some participants in the study described an ‘invest-to-save' model, which was thought to be true in the implementation of group consultations, requiring greater time commitment in the early stages of implementation but which would reduce as they were embedded. This however, has not been demonstrated and requires a collection and sharing of robust evaluation data both locally and nationally, along with collaborative working between both general practices and CCGs. The implementation and sustainability of the approach depends on the context surrounding general practice. The need to engage with digital approaches of care raises questions of the viability of group consultations in the future.

CONCLUSION

The set-up and delivery of group consultations from the experiences of healthcare professionals, provides a unique and novel insight into the barriers, facilitators and key roles of this approach. Whilst group consultations are effective in improving cohesiveness between teams, reducing consultation time and promoting patient and staff education, the lack of implementation and concerns regarding facilitation are aspects of this approach which requires consideration. Key roles and practicalities surrounding the set-up and delivery must be supported by a clear implementation plan, effective facilitation and whole practice engagement. The future of general practice therefore depends on an open-mindedness to adopt and evaluate new practices and reform to newer and more efficient ways of working to meet the needs of the current patient population.

REFERENCES

1. Baird B, Charles A, Honeyman M, et al. Understanding pressures in general practice. The Kings Fund: London; 2016 https://www.kingsfund.org.uk/sites/default/files/field/field_publication_file/Understanding-GP-pressures-Kings-Fund-May-2016.pdf.

2. NHS England. The NHS Long Term Plan. 2019. https://www.longtermplan.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/nhs-long-term-plan-version-1.2.pdf

3. The Kings Fund. Primary care networks explained. The Kings Fund; London. 2020 https://www.kingsfund.org.uk/publications/primary-care-networks-explained

4. NHS Digital. Quality Outcomes Framework. 2021. https://qof.digital.nhs.uk/

5. Craig G. Group consultations: better for patients, better for nurses?. Practice Nurse 2017;47(4):15-18.

6. Craig G, Nelson S. How group consultations are changing respiratory care. Practice Nursing 2019;30(3):136-139.

7. Birrell F, Brady L, Jones T. Group consultations: Benefits and implementation strategies. Practice Nursing 2018;29(10):484-488.

8. Booth A, Cantrell A, Preston L, et al. What is the evidence for the effectiveness, appropriateness and feasibility of group clinics for patients with chronic conditions? A systematic review. Health Services and Delivery Research. 2015;3(46):1-193.

9. Wadsworth K H, Archibald T G, Payne A E, et al. Shared medical appointments and patient-centred experience: A mixed-methods systematic review. BMC Medical Practice. 2019;20(1):97.

10. Royal College of General Practitioners. Spotlight on the 10 high impact actions. 2018. https://www.rcgp.org.uk/-/media/Files/Primary-Care-Development/RCGP-spotlight-on-the-10-high-impact-actions-may-2018.ashx?la=en

11. NHS England. GP Five Year Forward View; 2016. https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/gpfv.pdf

12. Gandhi D, Craig G. An evaluation of the suitability, feasibility and acceptability of group consultations in Brigstock Medical Practice. Journal of Medicines Optimisation 2019;5:39-44.

13. Swaithes L, Paskins Z, Duffy H, et al. The experience of implementing and delivering group consultations in UK general practice. Br J Gen Pract 2021;71(707):e412-e422

14. Kirsh S R, Aron D C, Johnson K D, et al. A realist review of shared medical appointments: How, for whom, and under what circumstances do they work?. BMC Health Services Research 2017;17(1):113

15. Wherton, J, Shaw S, Papoutsi C, et al. Guidance on the introduction and use of video consultations during COVID-19: important lessons from qualitative research. BMJ 2020;4:120-123.

16. Jones T, Darzi A, Egger G, et al. A systems approach to embedding group consultations in the NHS. Future Healthcare Journal. 2019;6(1):8.

Related articles

View all Articles