B12 deficiency and replacement in general practice

Beverley Bostock

Beverley Bostock

RGN MSc MA QN

ANP Mann Cottage Surgery

PCN Nurse Coordinator Hereford

Practice Nurse 2022;52(7):8-11

News that patients with type 2 diabetes who are treated with metformin should be monitored for B12 deficiency means more patients are likely to require treatment – so teaching self-administration is an attractive option

Anaemia comes from the Greek words an and aemia, meaning without blood. There are many different types of anaemia, one of which is vitamin B12 deficiency anaemia. In this article, we discuss why B12 deficiency occurs, how it is diagnosed, and the impact of B12 deficiency on the body. We also cover different approaches to B12 replacement, including self-administration. Finally, we consider recommendations regarding ongoing monitoring.

By the end of this article, the reader will be able to:

- Reflect on the role of vitamin B12 in the body

- Recognise why B12 deficiency occurs

- Consider the place for oral and injectable replacement therapy

- Analyse the importance of ongoing monitoring

THE ROLE OF VITAMIN B12

Vitamin B12, also known as cyanocobalamin, is an important ingredient used by the body in the formation of red blood cells and deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA). It supports the healthy function of the brain, nervous system and cardiovascular system. Vitamin B12 occurs in foods of animal origin.1 In the stomach, hydrochloric acid and enzymes unbind the vitamin B12 from the food source so that it can combine with intrinsic factor to enable absorption further down in the small intestine. A lack of B12 will interfere with the production of healthy red blood cells, stopping them from forming and dividing in the normal way, so that they become large and misshapen and are unable to exit the bone marrow. As red blood cells are essential for carrying oxygen around the body, this can have important effects on health.

In cases of B12 deficiency, a full blood count will show a reduced haemoglobin (Hb) and a raised mean cell volume (MCV) indicative of the increased size of the red blood cells. This is referred to as a macrocytic (‘large cell’) anaemia and contrasts with the microcytic anaemia seen in iron deficiency, where the Hb is also reduced but the red blood cells are small and the MCV is low. B12 levels should always be tested with folate levels (also known as folic acid or vitamin B9) as folate may also be reduced in B12 deficiency. Similarly, if folate levels alone are measured and found to be reduced, treating folate deficiency without checking B12 levels can mask an underlying vitamin B12 deficiency, which if left untreated could lead to neurological problems. Neutrophils are almost always reduced in B12 deficiency and platelet levels are often low, too.2

WHY B12 DEFICIENCY OCCURS

The overall UK prevalence of vitamin B12 deficiency in the under 60s is approximately 6%, but this rises to as much as 20% in the over 60s, depending on the population being studied.3 Risk factors for B12 deficiency fall into three key groups – those where there is inadequate intake of dietary vitamin B12, such as may be seen in people following a vegan, plant-based diet.4,5 In other people the absorption of B12 is impaired, such as through surgical procedures, or because of the autoimmune disease, pernicious anaemia (PA), both of which impact on levels of intrinsic factor. Other risk factors for B12 deficiency include hazardous alcohol consumption and some medication use, such as metformin and proton pump inhibitors (PPIs). Bacterial infections of the stomach, such as Helicobacter Pylori, can also affect B12 levels.

As PA is an autoimmune disease, people with a personal or family history of autoimmune disease (including Crohn’s disease, thyroid disorders and Addison’s disease) may be at greater risk. In PA, the body makes antibodies that attack and destroy parietal cells that line the stomach, and which make intrinsic factor. The resulting inability to make the intrinsic factor prevents Vitamin B12 from being absorbed, irrespective of how much the individual takes in through their diet. Other groups of people who are known to have an increased risk of PA include people with blood group A, those with blue eyes or a history of early greying and those of Northern European and African descent. Women are also at greater risk than men.

SIGNS AND SYMPTOMS

For some people, B12 deficiency may have no symptoms. In those who are symptomatic, it may take years of B12 deficiency for symptoms to develop. People who are B12 deficient may look pale, feel exhausted, and complain of pins and needles, burning sensations or numbness in hands and feet or gastrointestinal symptoms such as nausea, diarrhoea, dyspepsia or heartburn. Other symptoms include brain fog, vascular disease and neurological conditions.7 Vitamin B12 helps to break down homocysteine in the body and people with B12 deficiency may have elevated levels of homocysteine which has been linked to conditions such as dementia, coronary heart disease and stroke.8 This is why it is so important to identify B12 deficiency and treat it. Of note, at this time, some symptoms of B12 deficiency are associated with long COVID so it is important to investigate symptoms such as tiredness and brain fog before putting them down to long COVID. The diagnosis of B12 deficiency requires careful history taking, examination and investigations.

THE IMPACT OF METFORMIN ON VITAMIN B12 LEVELS

Metformin-associated B12 deficiency is now recognised and annual testing of B12 and folate levels should be considered for people being treated with metformin. Although not fully understood, metformin-associated B12 deficiency may be due to alterations in small bowel motility which stimulate bacterial overgrowth, inhibition or inactivation of vitamin B12 absorption or alterations in intrinsic factor levels.9 It is now recommended that periodical dosing with vitamin B12 should be considered in patients with type 2 diabetes treated with metformin, especially if they have associated anaemia and/or peripheral diabetic polyneuropathy.10

ORAL OR INJECTABLE REPLACEMENT THERAPY?

In cases of dietary deficiency, where intrinsic factor levels and absorption are unaffected, NICE recommends either oral cyanocobalamin tablets 50–150 micrograms daily between meals or a twice-yearly hydroxocobalamin 1000mcg injection.3 NICE states that people following a vegan diet may need lifelong injections given every 2-3 months. In other cases of dietary deficiency, oral supplementation can be stopped once the vitamin B12 levels have returned to normal and the diet has improved.3

In PA, where the lack of intrinsic factor does not allow adequate B12 absorption, injections will be needed for life.

Non-prescribing clinicians and HCAs can administer vitamin B12 injections via a Patient Specific Direction (PSD), which is a signed instruction to administer a medicine to an individual who has been individually assessed by the prescriber. The prescriber should sign the PSD and should specify the name of patient and/or other individual patient identifiers, such as their patient identification number or date of birth, along with the name, form and strength of the medicine, the route of administration, dose, frequency, and start and finish dates.11 For vitamin B12 replacement in people with PA, this often means that on diagnosis, they will need a loading dose of six intramuscular injections of hydroxocobalamin 1000mcg over a period of 2 weeks, followed by maintenance therapy of one injection every three months for life.3 Interestingly, the Electronic Medicines Compendium12 recommends a slightly different approach to treating PA and other macrocytic anaemias without neurological involvement. It states that a dose of 250mcg to 1000mcg should be given on alternate days for one or two weeks, followed by a dose of 250mcg weekly until the blood count is normal. Thereafter, a maintenance dose of 1000mcg should be given every two to three months. In people with B12 deficiency and neurological involvement, EMC recommends a 1000mcg injection given on alternate days for as long as improvement is occurring, then reducing to 1000 mcg every two or three months.

SELF-ADMINISTRATION OF B12 INJECTIONS

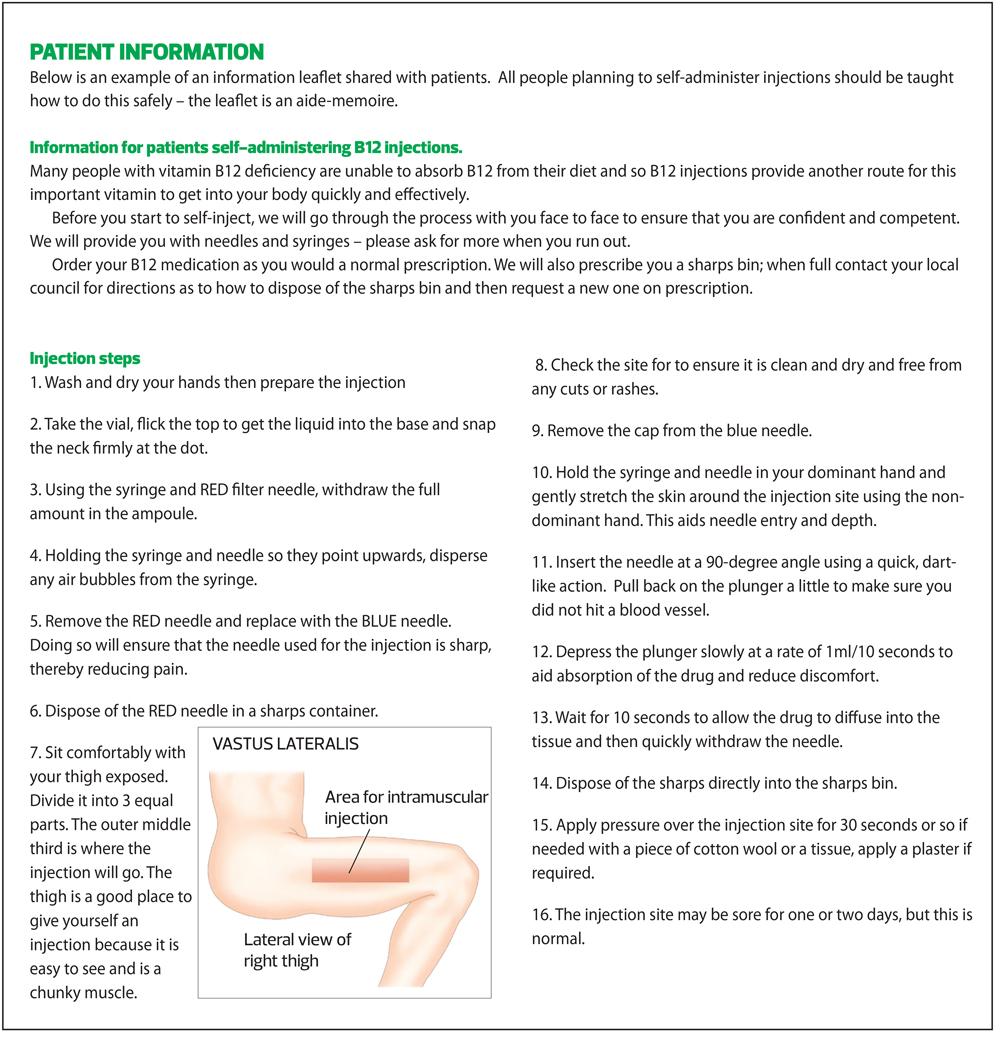

An increasing number of practices now support people who need B12 injections to self-administer, not unlike people with diabetes who use GLP1-RA injections or insulin, or people with rheumatoid arthritis who need injectable methotrexate. This could free up a lot of clinical appointments at a time when pressures on general practice are extremely high. From the patient perspective, self-administration can be more convenient. However, patient choice is key. Individuals should be encouraged to see self-administration as the norm. The risks of self-administration are minimal and overdose virtually impossible as excess B12 will be excreted via the urine.1

Examples of information leaflets to support self-administration are included in this article.

ONGOING MONITORING

NICE recommends repeating the full blood count and B12 levels at around 10 to 14 days to assess response.3 Another blood test may also be carried out after approximately 8 weeks to confirm the response. Routine blood testing after this is not usually indicated unless symptoms return. If an inadequate response occurs, the patient should be referred. If a folate deficiency has been identified, this should be treated with folate tablets, and levels checked again after 4 months.

ANAEMIA: CASE STUDIES

Note – normal values vary between laboratories so check local guidance. For these case studies, the following normal values are used:

- Haemoglobin: adult female = 11.5–16.5g/dl, male = 13–18g/dl

- Mean cell volume 80–100fL

- Vitamin B12 = 180–1000pg/mL

- Ferritin >15 micrograms/L

- Folate >4 ng/ml

Case study 1

Adele, age 33, complains of feeling tired all the time. She also has a history of heavy periods. She follows a vegetarian diet but admits that she eats more junk food than she should. Her blood tests are reported as follows:

- Hb 111 g/L

- MCV 72fL

- Ferritin 10mcg/litre

- B12 level 672 pg/ml

- Folate 6 ng/ml

Based on her history and results, Adele has iron deficiency anaemia, with a low Hb, low MCV and low ferritin levels. In contrast, her B12 and folate levels are both normal.

Case study 2

Arthur, age 42, also feels tired all the time. He works as a lorry driver and eats from service stations and roadside cafes. He finds it hard to concentrate at times. Arthur’s bloods show:

- Hb 121 g/L

- MCV 104fL

- Ferritin levels 25mcg/L

- B12 level 166pg/mL

- Folate 3.4ng/mL

Gastric parietal cell antibody test positive

Based on Arthur’s history and results, he has B12 and folate deficiency. His Hb is reduced and his MCV is raised, indicating a macrocytic anaemia. His B12 and folate levels are both reduced, and his positive gastric parietal cell antibody test confirms that he has PA and will require lifelong B12 injections. He will also need oral folic acid supplements for four months before his levels are rechecked.

SUMMARY

Vitamin B12 plays an essential role in many of the body’s systems. B12 deficiency can occur as the result of inadequate dietary intake or because of impaired absorption. Depending on the cause of B12 deficiency, oral or injectable replacement therapy will be recommended. In pernicious anaemia, lifelong B12 injections will be needed, and people may prefer to do these themselves in their own homes. Whether given by a healthcare worker or by the individual, correct procedures should be followed with regard to prescribing, injection technique, infection control and sharps disposal. Ongoing monitoring may be required.

REFERENCES

1. NHS. B vitamins and folic acid; 2020. https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/vitamins-and-minerals/vitamin-b/

2. Green R. Vitamin B12 deficiency from the perspective of a practicing hematologist. Blood 2017;129(19):2603–2611. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2016-10-569186

3. NICE Clinical Knowledge Summaries. Anaemia – B12 and folate deficiency; 2022 https://cks.nice.org.uk/topics/anaemia-b12-folate-deficiency/

4. Weikert C, Trefflich I, Menzel J, et al. Vitamin and Mineral Status in a Vegan Diet. Deutsches Arzteblatt international 2020;117(35-36):575–582. https://doi.org/10.3238/arztebl.2020.0575

5. Bakaloudi DR, Halloran A, Rippin HL, et al. Intake and adequacy of the vegan diet. A systematic review of the evidence. Clinical nutrition 2021;40(5):3503–3521. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clnu.2020.11.035

6. Ankar A, Kumar A. (2022). Vitamin B12 Deficiency; 2022. In StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK441923/

7. Pernicious Anaemia Society. Symptoms; 2022. https://pernicious-anaemia-society.org/

8. Ueno A, Hamano T, Enomoto S, et al. Influences of Vitamin B12 Supplementation on Cognition and Homocysteine in Patients with Vitamin B12 Deficiency and Cognitive Impairment. Nutrients 2022;14(7):1494. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14071494

9. Kibirige D, Mwebaze R. Vitamin B12 deficiency among patients with diabetes mellitus: is routine screening and supplementation justified?. J Diabetes Metab Disord 2013;12(1):17. https://doi.org/10.1186/2251-6581-12-17

10. Albai O, Timar B, Paun DL, et al. (2020). Metformin Treatment: A Potential Cause of Megaloblastic Anemia in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Diabetes, metabolic syndrome and obesity : targets and therapy, 13, 3873–3878. https://doi.org/10.2147/DMSO.S270393

11. Wessex LMC. Patient Specific Directions (PSDs) and Patient Group Directions (PGDs); 2021 https://www.wessexlmcs.com/patientspecificdirectionspsdsandpatientgroupdirect

12. Electronic Medicines Compendium. Hydroxocobalamin 1mg in 1ml solution for injection; 2021 https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/product/5038/smpc

Related articles

View all Articles