Preceptorship: supporting transition into primary care

Tracey O’Keeffe

Tracey O’Keeffe

MA Education, BSc Critical Care, RN

Education Facilitator

Practice Nurse 2021;51(3):26-31

General practice brings different challenges to learning strategies. A programme of preceptorship, to support the transition of newly qualified nurses, more experienced nurses and allied health professionals to primary care can enable the development of skilled and confident practitioners

The concept of preceptorship is not new and the importance of preceptorship for the newly-qualified nurse has been recognised by the Nursing and Midwifery Council (NMC) for some time.1 The ‘Principles of Preceptorship’ by the NMC suggests that the process should help individuals integrate smoothly into their new role, benefitting both employer and employee. A structured approach to support transition towards autonomous clinical practice is also reiterated by the Department of Health (Box 1),2 enabling the development of skilled, confident practitioners who feel valued, positively affecting both recruitment and retention, and the delivery of quality patient care.1

Preceptorship often focuses on the newly-qualified nurse (NQN),3,4 but it is also clear that the approach can be useful in other professional groups,5 as well as embracing more experienced individuals as they transition to a different working environment. This concept of context change is important in relation to primary care and is the focus of this article, together with an example of how a structured approach works in practice.

PRECEPTORSHIP IN PRIMARY CARE

Challenges with the primary care workforce and, specifically with General Practice Nurses (GPNs), has been highlighted over recent years,6 and strategies have been put in place to try to ensure stability and growth.7 Concerns include an older than average demographic: many GPNs are nearing retirement, and the GPN career pathway is not traditionally seen as usual or suitable for the NQN. To recruit both graduates and more experienced nurses into general practice it is essential that support mechanisms are in place to enable them to develop skills at a pace that is both safe for patient care and useful for service delivery. Preceptorship is one such structured process that could ameliorate the workforce situation by attracting employees and nurturing them through the initial stages of their role. To this end the Devon Training Hub (DTH) GPN Preceptorship Programme was set up.

THE STRUCTURE AND DESIGN OF THE PROGRAMME

The experience of nurses coming into employment in primary care for the first time can be varied. The DTH GPN Preceptorship Programme is designed for both NQNs and nurses new to general practice. In addition GP practices are all different. They have their own strengths and challenges and vary from large teaching practices to much smaller, and possibly geographically remote, centres. Unlike large secondary care trusts, which have learning and development departments and human resource infrastructure, the capacity to develop new educational initatives is more limited in an individual practice. With this in mind, we were really keen to create a pathway for nurses choosing primary care in Devon, which would be supportive and nurturing, while still challenging them so they could move forward in their new career.

The course is 12 months long, requiring one or two days per month out of practice to attend face-to-face training sessions. The programme is supported with regularly updated training materials, which also contain introductory information, contact details, reflection templates and meeting record sheets for the preceptee to use with their preceptor.

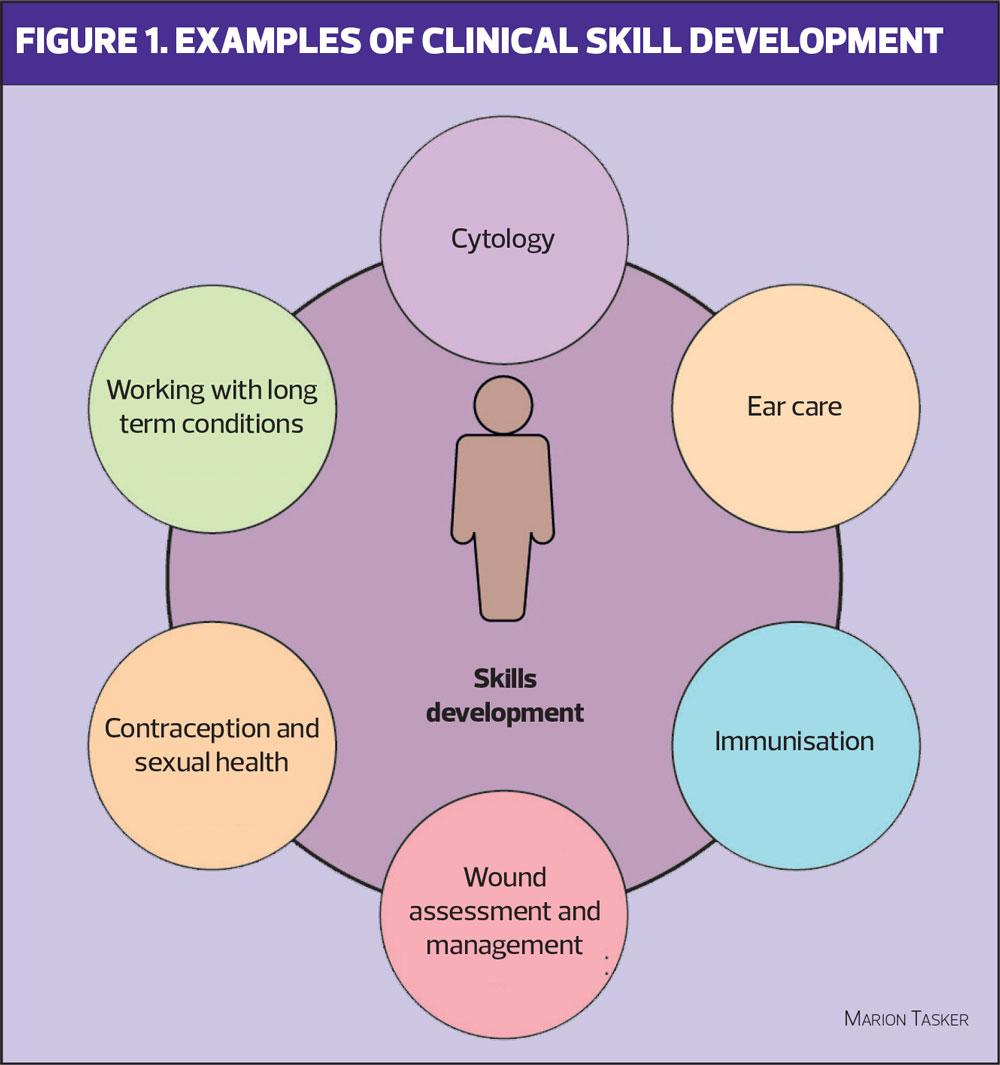

The programme provides a flexible way for practices to upskill newly recruited nurses and for the nurses to gain those skills quickly and effectively. The programme is front loaded during the first six months with core skills development; a foundation of knowledge of long-term conditions, including asthma, COPD, hypertension and diabetes, (Figure 1); and an insight into primary care. The second six months allows some scope for ad-hoc adjustment and creativity to suit each individual cohort’s needs and consists of an enrichment element of Action Learning Sets (ALS) and peer support sessions.

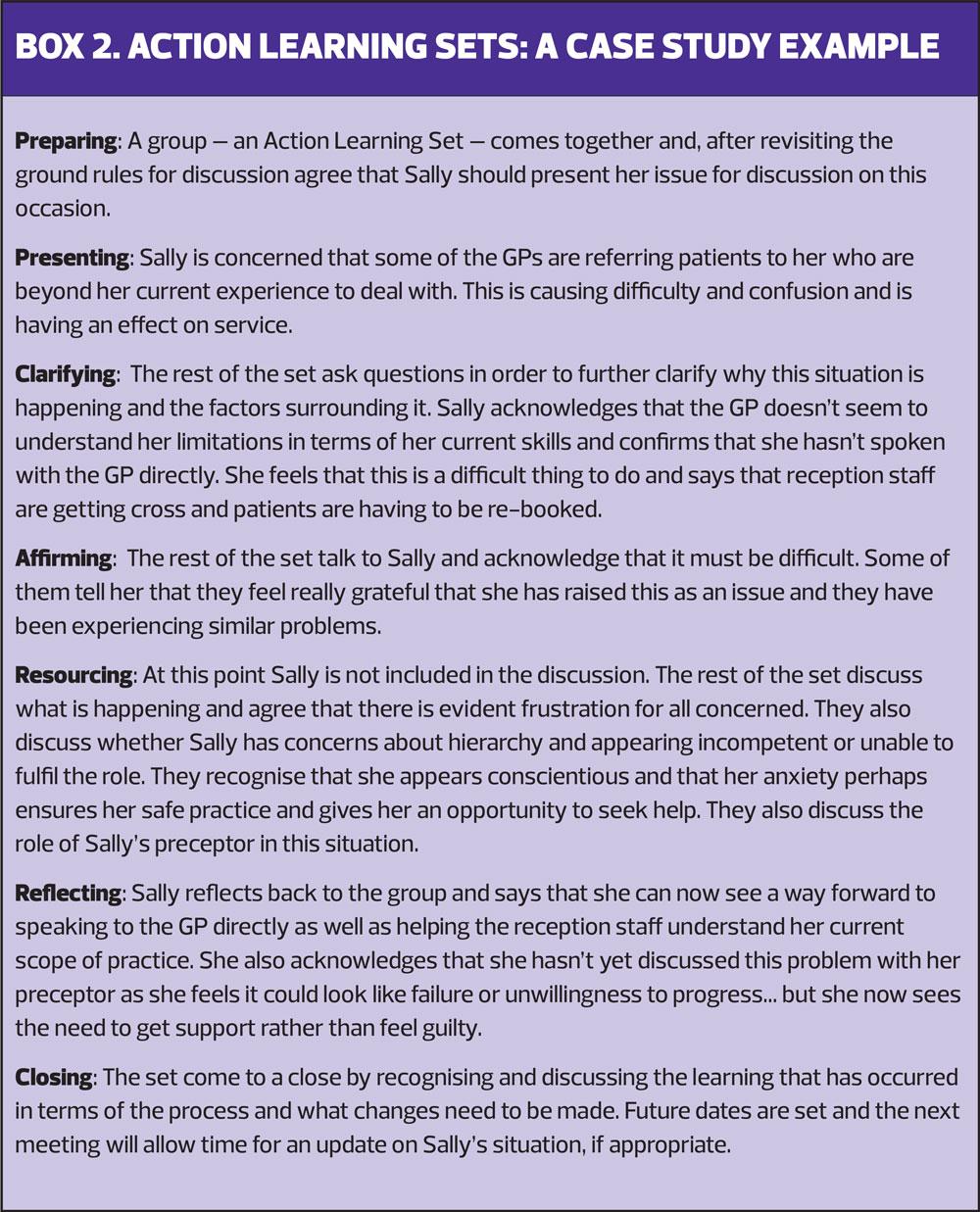

Action Learning Sets

ALS support individuals to explore a situation or issue with others in a group setting. They follow a structured format, based on active listening and challenging, but non-judgemental questioning. Confidentiality and trust are inherent, as is the belief that an individual has the ability to be empowered to find a solution-focussed way forward. Box 2 provides a case study of ALS.

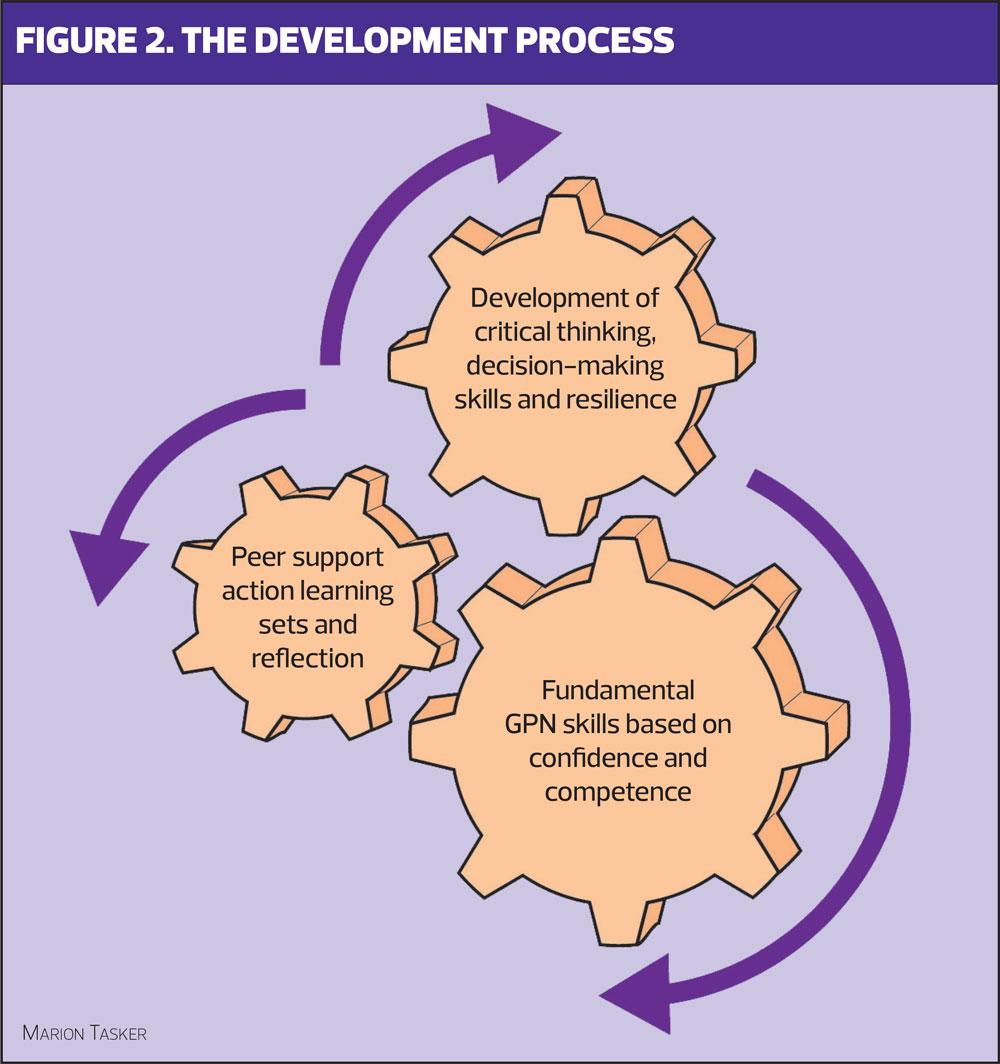

In designing the Preceptorship Programme we were very aware that there is pressure on both the nurses and the practices from the very start. Much of this stems from finance and ensuring that the GP practice is a viable business that can provide quality patient care and treatment. It is therefore essential that the workforce reaches a level of competency quickly and efficiently. For a nurse new to primary care, this can feel like a hierarchy in terms of what is important, with attaining the relevant skills as the main priority. We wanted to ensure that those skills were achieved but that this was wrapped around a strong net of peer support and reflection. We tried to steer away from the hierarchical approach and instead tried to see it as a set of interlocking ‘cogs’ of development (Figure 2).

LEARNING DURING THE PROGRAMME

Learning is the key focus of any preceptorship model but the way that it is achieved and role of the preceptor can be confusing and varied,8 and evidence for the effectiveness of the concept in primary care is scanty.9 There is also some question about whether the development of confidence and competence comes from the individual one-to-one time between preceptee and preceptor, or the structure of the programme itself.10 Addressing the two concepts of confidence and competence can be a way of exploring the start of a preceptee’s journey.

Confidence and competence

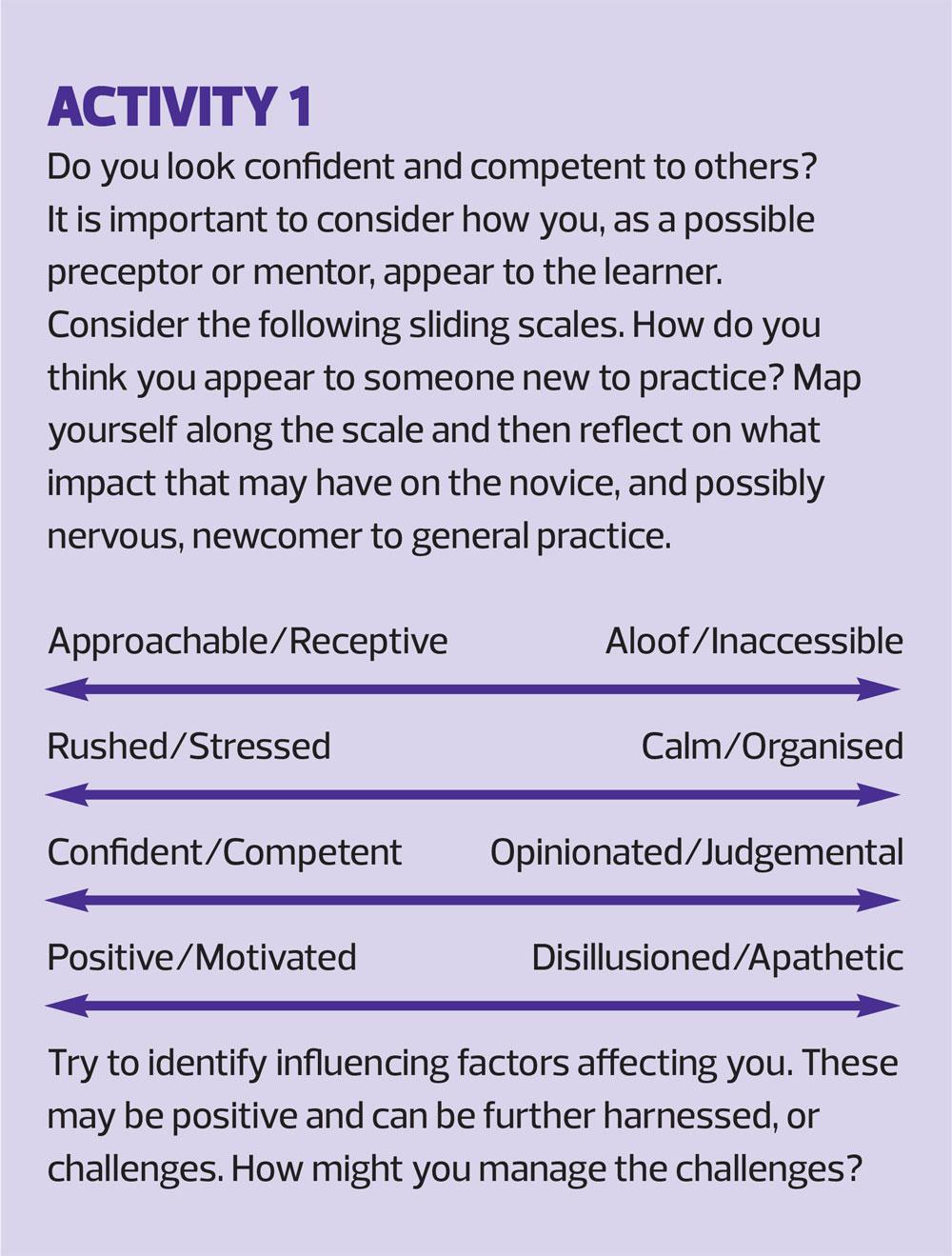

Learning comes from the baseline of where the individual currently is. We encourage our learners to identify their areas of confidence and insecurity from the start. We also ask them to think about how they present themselves to others: ‘Do you look confident and competent to others?’.

The perception of others has the potential to impact on how much support the individual receives and also how much expectation is placed on them. Without the willingness of the preceptee to show some vulnerability, potential anxiety and honesty about their feelings it can be difficult for their peers and managers to recognise the input needed. We were aware that many preceptees felt they needed to be strong and get on with the work, but were perhaps unaware that this could be seen as misplaced confidence and competence. There is undoubtedly some reciprocity required in this openness and it may therefore be useful for the preceptor and the wider team to consider their own self-awareness of how they present to others (see Activity 1).

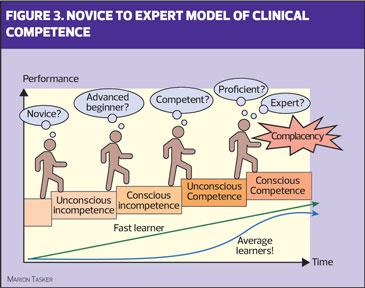

As we developed the DTH Preceptorship Programme, we also wanted to think about what our aim was in terms of development of clinical practice and how that translated to our teaching and support of each individual. We use the Conscious Competence Model, developed in the 1970’s by Noel Burch, to discuss a stepped approach to learning and how that might occur and feel for the individual, recognising, of course, that their progression will be unique to them. In view of that, and considering how many skills are learnt during preceptorship, it is perhaps important to also consider what is a realistic achievement for a transitional programme such as this. By mapping Benner’s Novice to Expert model of clinical competence,11 on to Burch’s framework (Figure 3), preceptorship is aiming for a level of ‘conscious competence’ and associated practice which is ‘competent’, or perhaps ‘proficient’. It would seem unrealistic to aim for expert and, for some, their conscious competence may still feel very much like an ‘advanced beginner’.

Using this type of framework has many advantages, but two in particular are pertinent to preceptees. First, it allows the individual to identify their own needs and acknowledge the normality of variation in learning progression as they transition into a GPN. Second, it highlights the higher levels of competence and learning in terms of goals and ambition, but also with regard for the need for life-long learning to avoid complacency in clinical practice. Arguably, being ‘unconsciously competent’ gives a sense of not thinking or processing the actions being carried out, and may not therefore be something that clinicians should aspire to.

A MODEL OF PRECEPTORSHIP LEARNING

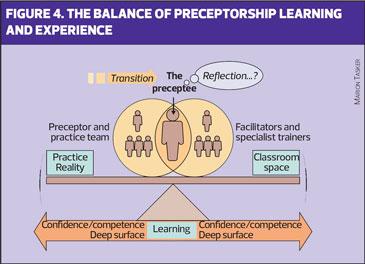

Our aim with preceptees was to start them thinking about their own personal learning from the start, but to also consider how that fitted with the wider picture of their individual practice, the Primary Care Network and the people using their service. This created for us a sense of balance regarding what we needed to deliver and how that would look in terms of supporting the individual preceptee. This perspective of balance can be seen as part of a model of preceptorship learning and experience (Figure 4), based on a continuum of learning structured around ‘classroom space’ and ‘practice reality’.

A model of personal change

Learning is a journey and preceptorship can be seen as the vehicle of transportation. The vehicle needs to enable a movement from one place to another. The concept of ‘transition shock’,12 is explored at initial induction as well introducing the learners to John Fisher’s 2012 model of personal change. See Activity 2.

Although this model is focused on change within organisations, it clear that it resonates with individuals as they face internal changes through the transition period of a new role. They may have to cope with feelings such as anxiety or disillusionment before being able to move forward more positively. Dealing with this transition is a potential stressor and may influence an individual’s ability to progress, learn and thrive. By recognising it and acknowledging it as acceptable, they are in a better position to initiate and utilise support mechanisms.

Support mechanisms

As well as emphasising to the preceptees the importance of working closely with their preceptor, the programme has embedded within it support mechanisms in the form of reflection and ALS. These concepts are taught at the very start. Both processes enable exploration of experiences relevant to the individual and their context of practice.

The power of reflection is enhanced by the individuals choosing their own unique situations,13 and by selecting areas which are both challenging and positive.14 Reflection and ALS complement each other by providing time for introspective thought as well as peer learning and discussion to pick apart the ‘wicked’ problems,15 associated with healthcare complexity. The underlying driver here is to also ensure that learning is both ‘surface and deep’. Learners can benefit from both levels of understanding.16,17 Embracing the validity of both is essential as their value is dependent on the transition point of that individual at that time, and for that specific skill or element of practice. The combination of ‘classroom space’ for exploring theory, and ‘practice reality’ for skill development and feedback is also a powerful mechanism to allow understanding to flourish and clinical ability to grow safely.

ROLL OUT

We commenced our first cohort in March 2019 and since then we have had five further cohorts, the most recent starting in January 2021. The current cohorts vary in size from three to 15 because we do not want to keep people waiting if there is a need for the programme. To delay risks valuable time being lost, and potential uncertainty and anxiety that could lead to a future GPN leaving their chosen career pathway before they have even really begun to flourish. If we have four people needing to start, then we will roll out a cohort.

Our latest cohort is different in that it is composed of nurses, both NQN and those with experience in other healthcare environments, and some Allied Health Professionals (AHPs) – paramedics and occupational therapists – and a nursing associate. AHPs are becoming a more vital component of the general practice workforce and this mix of experience and perspective can be valuable in enhancing the learning experience of all participants.

OUTCOMES

Attrition rates from the programme are low. Only 5% of participants (2 individuals) have decided to leave their roles in primary care. Feedback so far has been fantastic.

- ‘The Action Learning Sets reflect real life. They help us to reflect and it helps to know that others have problems too.’

- ‘Being in a cohort of people at a similar stage was really helpful. My favourite part of preceptorship is the support we shared among us. It was invaluable when first starting out as a GPN and we will continue to support each other post-preceptorship through our WhatsApp chat.’

We have observed each individual grow and develop in confidence as they progress. The success of the programme is evident as we see more GP practices taking on NQNs as well as those with experience. Practice managers and nurse managers both now come to the Training Hub as the ‘go-to’ place for them to enrol their new nurses on a preceptorship programme, confident in the knowledge that we will support both the nurse and them as a practice.

NEXT STEPS

Course development is dynamic. Elements have been adjusted to ensure they reflect the key components of the QNI guidance on induction requirements for nurses entering general practice (see suggested reading and resources). The inclusion of other clinicians entering primary care is innovative and the benefits of inter-professional education provide an opportunity to further enhance the programme. Applications are also starting to come in for Return to Practice nurses, as well as Nursing Associates.

Our key aims include ensuring ALS are firmly embedded early on, as well as providing a greater degree of flexibility to mirror the different learner needs. Experience so far has shown that careful timetabling ensures challenges are spaced appropriately to allow completion and reduce overload, which is perhaps even more relevant in the current COVID pandemic.

THE COVID IMPACT

The COVID pandemic has affected the delivery of all teaching. As COVID and the first, full lockdown hit, we had three existing cohorts. The effect on the first group was negligible as essentially they had completed the programme, but for the two groups part-way through there were challenges.

Cohort 2 had already had the opportunity to meet face-to-face a number of times, which meant connections had been made. They knew us and they knew each other and, very importantly, had been able to create closer bonds in smaller groups for peer support. However, there was also a sense of loss as they had to adjust to something different. For Cohort 3, the immediate impact seemed greater at the outset as they had barely got going and relationships had not been built. They still had that sense of newness and vulnerability.

Face-to-face meetings were out of the question and we had to work out how best to support these nurses. We needed to ensure that they were safe at work in their practices and moving forward with their education so that they felt like they were making a useful contribution in their practice teams and growing as individuals. Learning has been transformed to a more remote style. The immunisation foundation course, for example, has been adapted to a blended type of learning, with a mix of virtual classroom and online learning. We have also offered regular tutorials with the preceptees and kept in touch with their mentors in practice to ensure that they have the support they need.

SUMMARY

We will not let COVID get in the way of us working with nurses and practices to guide these new arrivals towards safe practice and a fabulous role in general practice in Devon. The Training Hub continues to expand opportunities and develop the preceptorship programme as a robust starting point on a career pathway for newly-qualified and more experienced nurses and clinicians. Success comes from flexibility, communication and collaboration alongside creative teaching and robust support systems.

REFERENCES

1. Nursing and Midwifery Council. Principles of preceptorship. July 2020. https://www.nmc.org.uk/globalassets/sitedocuments/nmc-publications/nmc-principles-for-preceptorship-a5.pdf

2. Department of Health. Preceptorship framework for newly registered nurses, midwives and allied health professionals. 2010. https://www.networks.nhs.uk/nhs-networks/ahp-networks/documents/dh_114116.pdf

3. Quek G J H, Shorey S. Perceptions, experiences, and needs of nursing preceptors and their preceptees on preceptorship: an integrative review. J Prof Nurs 2018;34(5):417-428. doi: 10.1016/j.profnurs.2018.05.003.

4. Marks-Maran D, Ooms A, Tapping J, et al. A preceptorship programme for newly-qualified nurses: a study of preceptees’ perceptions. Nurse Educ Today 2013;33 (11): 1428-34. doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2012.11.013. Epub 2012 Dec 20.

5. Fernald D H, Staudenmaier AC, Tressler C J, et al Student perspectives on primary care preceptorships: enhancing the medical student preceptorship learning environment. Teach Learn Med 2001;13(1):13-20 doi:10.1207/S15328015TLM1301_4. 2001.

6. Queen’s Nursing Institute. General practice nursing in the 21st century; a time of opportunity. 2015 https://www.qni.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/gpn_c21_report.pdf

7. NHS England. General practice – developing confidence, capability and capacity: a ten point action plan for general practice nursing. 2017. https://www.england.nhs.uk/publication/general-practice-developing-confidence-capability-and-capacity/

8. Price B. Preceptorship of nurses in the community. Prim Health Care 2014;24(4):36-41.

9. Walker SH, Norris K. What is the evidence that can inform the implementation of a preceptorship scheme for general practice nurses, and what is the evidence for the benefits of such a scheme?: a literature review and synthesis. Nurs Educ Today 2020; 86. doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2019.104327. Epub 2020 Jan 7. 2020.

10. Irwin C, Bliss J, Poole K. Does preceptorship improve confidence and competence in newly qualified nurses: a systematic literature review. Nurse Educ Today 2017;60:35-46. doi: 10:1016/jnedt.2017.09.011. Epub 2017 Sept 28.

11. Benner P. From novice to expert. Am J Nurs 1982;82(3):402-407

12. Boychuk Duchscher J. Transition shock: the initial stage of role adaptation for newly graduated registered nurses. J Adv Nurs 2009;65(5):1103–1113

13. Cunningham B. Exploring professionalism. London: Institute of Education, University of London. 2008.

14. Dixon M, Lee S, Ghaye T. Strengths-based reflective practices for the management of change: applications from sport and positive psychology. J Chang Manag 2016;16(2):142-157

15. Rittel HJW, Webber MM. Dilemmas in a general theory of planning. Policy Sci 1973;4(2):155-169

16. Donnison S, Penn-Edwards S. Focusing on first year assessment: surface or deep approaches to learning? Int J First Year in Higher Education (FYHE) 2012;3(2):9-20. doi: 10.5204/intjfyhe.v3i2.127

17. Dolmans DH JM, Loyens MM, Marcq H, et al. Deep and surface learning in problem-based learning: a review of the literature. Adv In Health Sci Educ 2016;21:1087-1112. doi: 10.1007/s10459-015-9645-6

Related articles

View all Articles