Reviewing patients with epilepsy: a role for the practice nurse?

DR RICHARD HILLS

DR RICHARD HILLS

MB ChB (Sheffield), D.A. (UK), FRCGP;

GPwSI in Epilepsy and Movement Disorders, University Hospital of Coventry and Warwickshire;

Salaried General Practitioner, Engleton House Surgery, Coventry;

Chair of GP Epilepsy Society of UK Chapter of the International League against Epilepsy

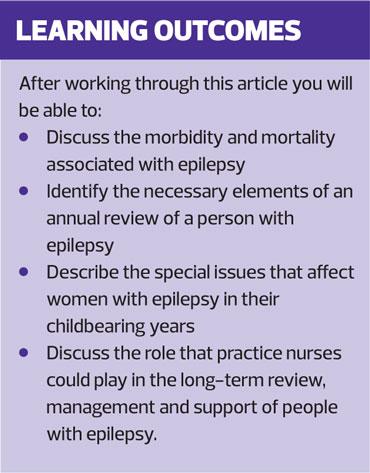

A structured review of all patients with epilepsy should be an annual event. General practice nurses could have a lead role in this process, or may identify issues for patients with epilepsy through encounters for unrelated reasons

Epilepsy is a common neurological condition. At any one time it affects about 1% of the population.1 The International League against Epilepsy, defines an epileptic seizure as: ‘a transient occurrence of signs and/or symptoms due to abnormal excessive or synchronous neuronal activity in the brain.’

It defines epilepsy as: ‘a disease characterised by an enduring predisposition to generate epileptic seizures, and by the neurobiological, cognitive, psychological, and social consequences of this condition.’2

In other words, a seizure (of which there are about 40 different types) is the symptom, and epilepsy is a brain condition causing recurrent unprovoked seizures, often unpredictably. It is beyond the scope of this article to explore the classification of epilepsy comprehensively but, broadly speaking, adult epilepsy is either localisation related or idiopathic generalised.

As the definition indicates, the impact of epilepsy (and its treatment) has much wider implications than just the seizures, which is why regular review is so important.

WHY EPILEPSY CARE IS IMPORTANT

Good epilepsy management is important for reducing:

- Mortality associated with epilepsy

- Morbidity

- The impact the condition has on a patient’s quality of life.

The standardised mortality rate for patients with epilepsy is 2-4 times higher than the general population.3 The causes of death included accidents, status epilepticus, suicide, and Sudden Unexpected Death Syndrome (SUDEP).

Morbidity associated with epilepsy includes accidents, medication related problems, mental health problems, and the social impact of the condition, including employment issues, driving, financial hardship and benefits.

For women suffering from epilepsy, there are additional issues. These include antiepileptic drug (AED) interactions with contraception and the need to address the impact of the condition and its treatment on pregnancy (mother and fetus), and postnatal issues.

The stigma of epilepsy remains a significant burden for sufferers.

SUDEP AND THE CHALLENGE FOR PRIMARY CARE

NICE estimates that there are 500 deaths from SUDEP per year.4 The risk increases with seizure frequency (generally speaking, SUDEP is a seizure related event) and there is a greater association with:

- Younger sufferers, particularly young men

- Lower IQ

- Poor medication adherence

- Generalised tonic-clonic seizures, and

- Sleep-related seizures, particularly when the patient sleeps alone.

The cause of death in these cases is currently unknown. A population based study found that patients with alcohol problems in addition to epilepsy had an almost threefold increased risk of death.5 There was also an almost twofold risk increase in the patient who had not collected their most recent anticonvulsant prescription in the past 3 - 6 months, and a 40% increase if there was a ‘a history of injury’ in the past or having had treatment for depression.5 In her BMJ editorial, Leone Ridsdale challenges primary care to use risk assessment tools to identify those patients at greatest risk and manage or refer where necessary.6

NICE ON EPILEPSY

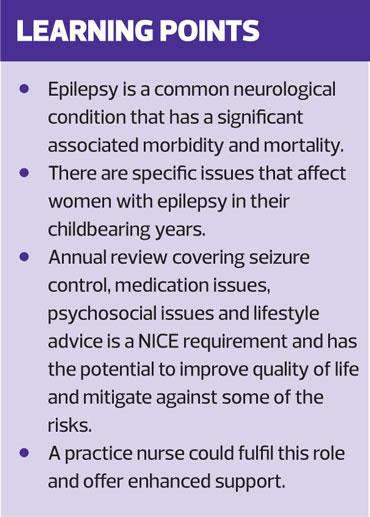

The NICE guideline on epilepsy (CG137),4 recommends that all adults with epilepsy have a regular, structured review with their GP at least yearly, although this can be carried out by the specialist if circumstances or the patient’s wishes dictate.

The review should include looking at the patient’s AED in relation to side effects and adherence to medication. The review may lead to referral into secondary or tertiary care for a review of the diagnosis, investigation and treatment if poor seizure control is identified. Other medical or lifestyle issues, such as preconception advice, pregnancy or drug cessation may also prompt referral for specialist review.

In my experience, structured reviews need to be tailored to the patient’s needs. Some remain seizure free, side effect free, and happy to continue to take their medication given an unchanged lifestyle context. Others have on-going or newly recurrent seizures, medication issues or changes in their situation which require a much more detailed assessment.

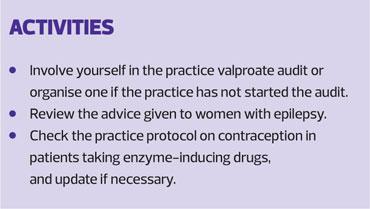

NICE updated the guideline in April 2018. Amongst the areas that directly affect primary care are an imperative to make sure that information is or has been provided about SUDEP, and that further reinforcement of the issues concerning valproate in women has been given (see below). NICE advises that information and advice should be given to women and girls with epilepsy concerning AEDs and contraception, conception, pregnancy, caring for children, breastfeeding and menopause.

THE PATIENT WITH EPILEPSY AND THE TRAINED PRACTICE NURSE

A review of all published evidence between 1992 and 1999 examined the effect of specially trained epilepsy nurses in primary care.7 The impact of these practice nurses included an increase in the rate of creation of disease registers for patients with epilepsy – a first, vital step to improving care.

Invitation for nurse review was accepted by between 52% and 83% of patients. In addition it was found that these patients had a higher level of expectation beforehand, and satisfaction afterwards, compared with GPs or Specialists. In one study, it was found that patients were more likely to be honest with the practice nurse about such issues as missing medication. There was an increase in recorded advice about driving, drug compliance, drug side effects, alcohol and provision of information about self-help groups and patient organisations.

Patients with active seizures are more likely to be suffering from depression and/or anxiety; studies looking at nurses in a counselling and support role demonstrated that they had positive impacts. Another study found that the liaison role of the practice nurse was valued both by patients and doctors, that the need for specialist follow-up visits was reduced, and that specialist nurses were also able to organise rapid access to the specialist when necessary. In one service in Doncaster, nurses were able to provide emergency advice, which might reduce the use of unscheduled care.

There are plenty of examples where extending roles, with the appropriate training, can make a significant impact. But I would argue that even without additional training, practice nurses and advance nurse practitioners are in an ideal position to identify medication compliance problems and mental health and alcohol issues, as well as requests for advice about contraception, preconception or bone health.

A TEMPLATE FOR REVIEW

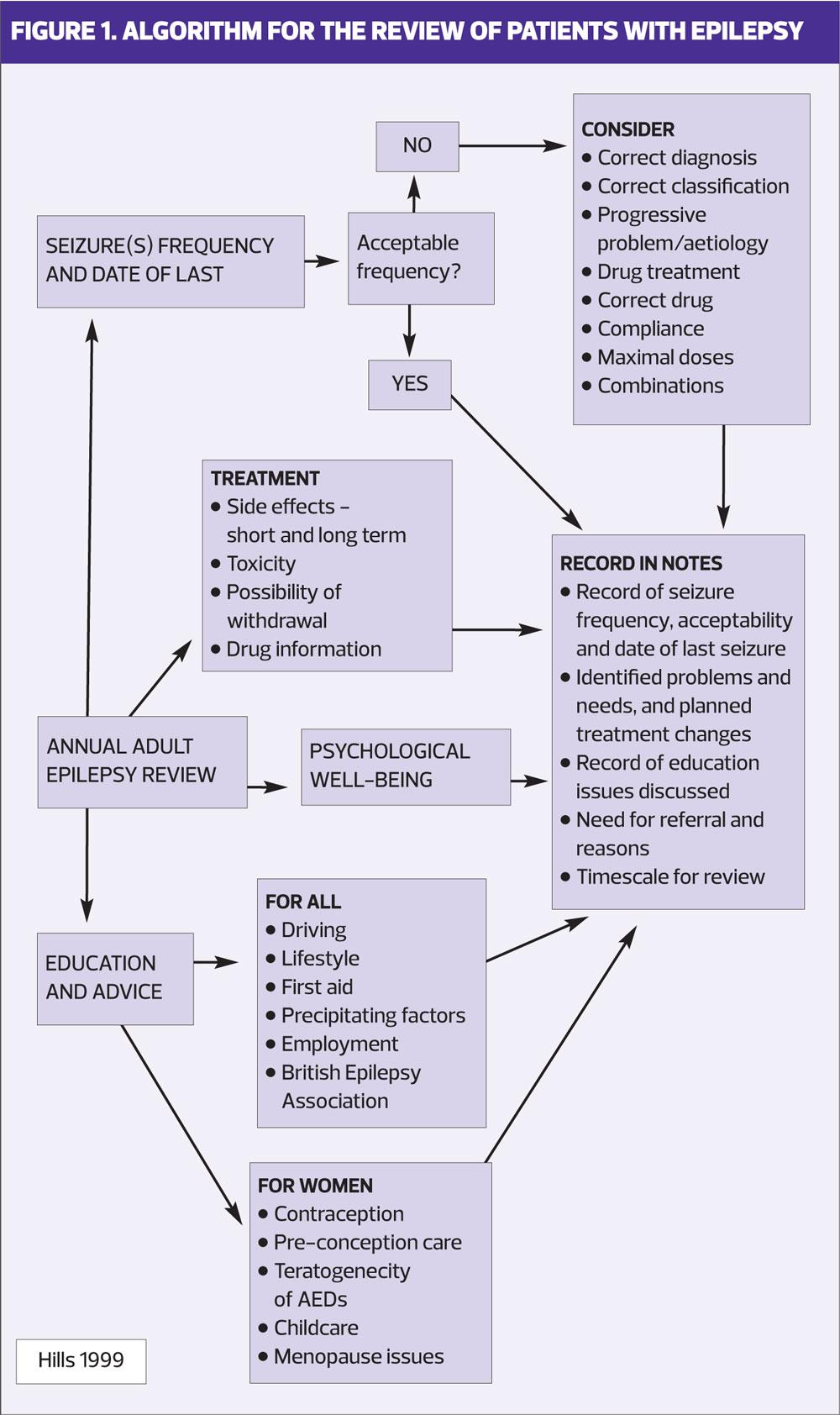

My own template for reviewing patients with epilepsy is summarised in Figure 1. I designed this in 1999 and little has changed as far as the areas that may need to be covered, although bone health could be specifically added to long-term side effects.

The burden of epilepsy for sufferers primarily pertains to the seizures and their treatment. Those patients whose seizures are quiescent and whose treatment is well tolerated are likely to experience least impact on their quality of life, although they may not escape the social impact of their conditions. For instance, patients with epilepsy are less likely to be employed, get married or have children. Therefore, enquiring about seizure activity is a cornerstone of a review. Interestingly patients may under-report their seizures to their GPs; driving often being the main reason for their under-reporting.8

A patient who has active seizures is likely to be under the care of an epilepsy clinic or should be offered a referral. However, some patients may wish to tolerate the seizures because they are not intrusive or because they have already experienced the burden of AEDs. It is important to establish that the patient is fully aware of their options, and of the risk of seizures, particularly SUDEP.

Record seizure frequency or seizure freedom, and the date of their last seizures. This is very helpful for retrospective reviews and, if seizure free, for driving licence applications.

MEDICATION REVIEW

It is always important to ask about general issues with patient’s treatment. For the majority of AEDs, tolerability is unlikely to change in the long term. However, that may not be the case when the addition of other drugs causes interactions, there is significant weight change or the patient develops other co-morbidities. Identifying problematic adverse reactions should result in considering a referral back to an epilepsy specialist.

Phenytoin is an older AED with multiple long term issues. Despite this, there are still a number of patients taking this medication today. Because of the possible impact on gums, patients should have a regular dental check-up. In the longer term, there is a risk of peripheral neuropathy or cerebellar damage, so it is important to ask about numbness in the hands and feet, and about problems with balance.

A number of AEDs, including phenytoin, carbamazepine, primidone, phenobarbital, topiramate, and a new drug, perampanil, are enzyme inducers. As a result, the interactions with other medication, such as oral contraceptives, can be significant and there can be effects on vitamin D levels – see below.

NICE does not recommend regular blood monitoring in adults and blood tests should be only done only if they are clinically indicated.4 The routine monitoring of blood levels of AED is not indicated in stable patients even with phenytoin. The evidence is that phenytoin levels do not correlate with long term toxicity.9 There are, however, exceptions relating to planning pregnancy. Levels of lamotrigine can drop quickly in early pregnancy, and having a preconception level for this medication can be very helpful. Levetiracetam levels can also drop in late pregnancy.

BONE HEALTH

In 2009, the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) published a summary of its review of the evidence in this area.10 It concluded that long-term treatment with the following drugs was associated with reduced bone mass and therefore increased risk of osteopenia, osteoporosis and fracture risk:

- Carbamazepine

- Phenytoin

- Primidone

- Sodium valproate.

These risks were enhanced by long periods of immobilisation, poor calcium intake and low levels of sun exposure. There is a poor understanding of the exact causation, but vitamin D metabolism is likely to be part of the mechanism.

The MHRA recommends vitamin D supplementation for all patients considered at risk. It is my practice to suggest 800-1000IU of vitamin D daily to all patients on enzyme-inducing AEDs and valproate. It may also be worth considering screening for fracture risk in later life.

CAN I STOP MY MEDICATION?

This is common question from patients who have achieved seizure freedom. AEDs control but do not cure epilepsy and, unfortunately, although investigations may help to estimate the risk of seizure recurrence on withdrawal they do not predict with any certainty that the seizures will not recur.

Appendix H in the NICE guidelines,4 contains very helpful risk tables based on length of seizure freedom, among other measures. They support the general principle that the longer the period of freedom from seizure, the lower the risk of recurrence. However, even maintaining the AED treatment does not completely mitigate against the risk of further seizures.

Withdrawal of AEDs should be managed by a specialist. However, it is worth having a discussion with the patient about their priorities. If their clear priority is to keep the risk of recurrent seizures to a minimum, then continuing the drug treatment is to be recommended. Driving is a critical part of modern life for many people and is the other dominant reason to continue treatment. During withdrawal, a voluntary cessation of driving during that period and for 3 to 6 months after withdrawal is a DVLA requirement. If the seizures recur then there will be a further period of suspension.

Encouraging medicine adherence should be part of any review as breakthrough seizures associated with missed doses of AED are a not uncommon experience in my clinic.

DRIVING

Advising patients about driving can be complicated and referral to the DVLA guide is recommended.11

In summary, patients have a legal duty to report seizures or other loss of consciousness episodes (provoked vasovagal episode being an exception) to the DVLA. Patients who have an isolated seizure will have a 6 months suspension and people with epilepsy (PWE) will need to be seizure free for 12 months before they can expect the return of their group 1 (private car and light goods van) licence.

The rules are different for sleep related seizures, seizures that do not involve loss of consciousness, symptomatic seizures (e.g. CVA related) and in certain conditions such as brain tumours or significant head injuries.

MENTAL HEALTH

Anxiety and depression is common. Some authors quote a lifetime prevalence of >50%.12 The risk is proportional to the frequency of seizures. However, depression is often missed, partly as the symptoms of depression in PWE may be atypical. It is important to identify, not only because of its effects on quality of life but also because suicide is a factor contributing to the higher standardised mortality rate in PWE.

Some clinicians use the Neurological Disorders Depression Inventory for Epilepsy (NDDI-E), a 6-item questionnaire to screen for depression that has been shown to be effective in case-finding.13 A Cochrane review of treating depression in patients with epilepsy found very limited evidence of significant benefit for antidepressant treatment.14 However, other reviews have suggested greater benefit although the studies reviewed may have been of a lower quality.12,15 All three papers found little evidence that antidepressants at therapeutic doses increase seizures.

WOMEN’S HEALTH

Contraception

Ideally, advice should be given to all women and girls with epilepsy (WWE) before they become sexually active. An annual review is an ideal opportunity to check on the patient’s current situation and awareness. Epilepsy does not restrict the use of any contraceptive methods, but issues arise with the enzyme-inducing AEDs listed above and lamotrigine, because they reduce the effectiveness of some hormonal contraceptives.

To summarise the advice for a woman taking enzyme inducing medication: the progestogen-only injectable, which is unaffected, or intrauterine method (copper intrauterine device [IUD] or the levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system [IUS]) remain highly effective contraception. If the patient prefers to use the combined oral contraceptive (COC) pill, then doubling the dose (i.e. 2 tablets daily), making sure that this results in a minimum dose of 50 micrograms of ethinylestradiol, is recommended. There is evidence that even with this increased dose, efficacy is still reduced, so some authorities recommend tri-cycling and/or reducing the pill free period to 5 days. More detailed advice is available from the Faculty of Sexual and Reproductive Heathcare.16

Lamotrigine, which is not an enzyme-inducing drug, may become less effective when using the COC and in reverse, can have an impact on the efficacy of the combined oral contraceptive. Progestogen-only methods, either orally or parentally administrated, do not affect lamotrigine levels nor are they affected by lamotrigine. The IUS or IUD also remain effective.

Pregnancy

An annual review is also an important opportunity to discuss pregnancy plans. If pregnancy is being considered, referral to an epilepsy clinic for preconception advice is critical. At this point, commence folic acid 5mg daily.

The clinic appointment will provide information concerning the increased risks of major fetal abnormalities and of developmental delay, and possible increased seizure frequency in pregnancy and the associated risk for both mother and baby. However, most WWE have a normal pregnancy and outcome. WWE do, however, have an increased background fetal abnormality rate of 3% when compared with the general population of 2% and AEDs can affect that further, although their impact does vary. In these circumstances the woman may decide to change AED to another with a more favourable profile, or stop medication altogether.

Sodium valproate (Epilim, Depakote and other generic brands), used in the treatment of epilepsy as well as bipolar disorder, presents a particular problem in pregnancy. It has long been known to be associated with a significant risk of birth defects (in the region of 10%) but, more recently, it has been discovered that about 40% of children exposed to valproate during pregnancy have developmental delays. The MHRA’s position is that valproate must no longer be used in any woman or girl able to have children unless she has a pregnancy prevention programme in place.17 NICE,4 advises that valproate treatment must not be used in girls and women, including in young girls below the age of puberty, unless alternative treatments are not suitable. A comprehensive case finding exercise in primary care is continuing to make sure patients are fully aware of the risks. Some of these patients may be picked up at the annual review.

CONCLUSION

Epilepsy remains a Cinderella condition; the retirement of Quality and Outcome Framework (QOF) points related to epilepsy review, is considered by many – including the author – as a backward and short-sighted decision. Despite this, reviewing patients with epilepsy in primary care on an annual basis is not only a NICE requirement, but is also necessary to re-evaluate the ongoing needs of the patient, and to identify any issues that could need intervention, either in primary care or by referral to an epilepsy clinic. It has been shown that general practice nurses and nurse practitioners can successfully fulfil this role and there are resources to support the necessary training to provide a comprehensive service.

In this article, I have set out the areas that need to be considered in such a review. Many of these will already be a typical part of your role, such as encouraging medication adherence, advising about contraceptive issues, preconception guidance, and general health issues, including bone health. Most of all, however, your skills in listening to patients and supporting them with their chronic illness(es) and associated impacts, and helping patients to make choices going forward for living with their condition(s) can be both satisfying for you and of immense benefit to the patients.

REFERENCES

1. Joint Epilepsy Council of the UK and Ireland. Epilepsy prevalence, incidence and other statistics. September 2011 http://www.epilepsyscotland.org.uk/pdf/Joint_Epilepsy_Council_Prevalence_and_Incidence_September_11_(3).pdf

2. Fisher RS, Van Emde Boas W, Blume W, et al. Epileptic Seizures and Epilepsy: Definitions Proposed by the International League Against Epilepsy (ILAE) and the International Bureau for Epilepsy (IBE). Epilepsia 2005;46(4):470-72

3. Cockrell OC, Johnson AL, Sander JW, et al. Mortality from epilepsy: results from a prospective population based study. Lancet 1994; 344:918-21.

4. NICE CG137. Epilepsies: Diagnosis and Management, 2012. Last updated: April 2018 https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg137

5. Ridsdale L, Charlton J, Ashworth M, et al. Epilepsy mortality and risk factors for death in epilepsy: a population-based study. Br J Gen Pract 2011;61:e271-8.

6. Ridsdale L. Avoiding premature death in epilepsy. British Medical Journal 2015; 350: h718

7. Ridsdale L. The effect of specially trained epilepsy nurses in primary care: a review. Seizure 2000; 9: 43-46

8. Dalrymple J, Appleby J. Cross sectional study of reporting of epileptic seizures to general practitioners. BMJ 2000;320:94

9. Stilman N, Masdeu J C. Incidence of seizures with phenytoin toxicity. Neurology 1985;35(12):1769-72.

10. Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency. Antiepileptics: adverse effects on bone. Drug Safety Update April 2009; 2 (9): 2.

11. Driver & Vehicle Licensing Agency. Assessing fitness to drive: a guide for medical professionals. c11 March 2016 [Updated 1 January 2018]. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/assessing-fitness-to-drive-a-guide-for-medical-professionals

12. Jackson M, Turkington D. Depression and Anxiety in Epilepsy. J Neurol Neurosurg Psych 2005;76(Suppl I):i45–i47

13. Friedman D, Kung D, Laowattana S, et al. Identifying depression in epilepsy in a busy clinical setting is enhanced with systematic screening. Seizure 2009; 18(6):429-433.

14. Maguire MJ, Weston J, Singh J, et al. Antidepressants for people with epilepsy and depression. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2014, Issue 12. Art. No.: CD010682. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD010682.pub2

15. Trivedi MH, Kurian BT. Managing Depressive Disorders in Patients with Epilepsy. Psychiatry (Edgmont) 2007;4(1):26-34.

16. Faculty of Sexual and Reproductive Healthcare. Drug interactions with hormonal contraception. c.January 2018. https://www.fsrh.org/documents/ceu-clinical-guidance-drug-interactions-with-hormonal/

17. Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency. Guidance. Valproate use by women and girls. Drug Safety Update 2018;11(9):1

Related articles

View all Articles