Central Nervous System: assessment and examination for general practice nurses

Sarah Cooper

Sarah Cooper

BSc (Hons) RGN, DipHE, FHEA

Lecturer in Adult Nursing Keele University, School of Nursing and Midwifery

Julie Reynolds

RGN, BSc (Hons) RNT FHEA MA Ed

Lecturer in Adult Nursing Keele University, School of Nursing and Midwifery

Andrew Finney

RN, Dip, BSc (Hons) RNT FHEA, PhD

Senior Lecturer in Nursing, Keele University, School of Nursing and Midwifery

Practice Nurse 2022;52(4):24-30

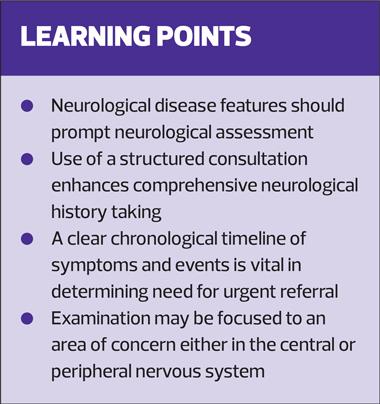

‘Neurological assessment’ are words which may strike fear into the hearts of any non-specialist clinician. This article aims to offer a practical, structured approach to assessment for general practice nurses in advanced roles who may detect neurological disease indicators

Neurological conditions are disorders of the brain, spinal cord, or nerves, and have a range of causes, some of which are not well understood.1

In the last 25 years, an expanding and ageing population has contributed to a global rise in the incidence of neurological morbidity and mortality to a position secondary only to cardiovascular diseases.2

However, it can be difficult for patients with neurological conditions to access high quality care. In many parts of the country the waiting time for a neurology appointment is well over a year. Inaccurate perceptions of the rarity of neurological disease, and the complexity of neurological assessment mean primary care practitioners may feel unprepared to assess patients with neurological presentations.1

General practice nurses – especially those working in advanced roles – can positively impact patient outcomes, and overall patient satisfaction, by increasing their knowledge of neurological assessment.3

Neurology is a specialist field and many clinicians appear to fear neurology assessment as inherently complex.4,5 In common with all fields of nursing you will need to bear to code of professional conduct in mind and take care not to exceed your scope of practice by undertaking further training and working with a mentor. That said, a structured approach to neurological assessment and examination, an overview of which is provided in this article, will allow you to recognise neurological symptoms so that you are able to refer appropriately to specialist services.6

HISTORY TAKING

Neurological conditions are frequently life altering, and their detection relies on a comprehensive consultation.7

Initiating the session

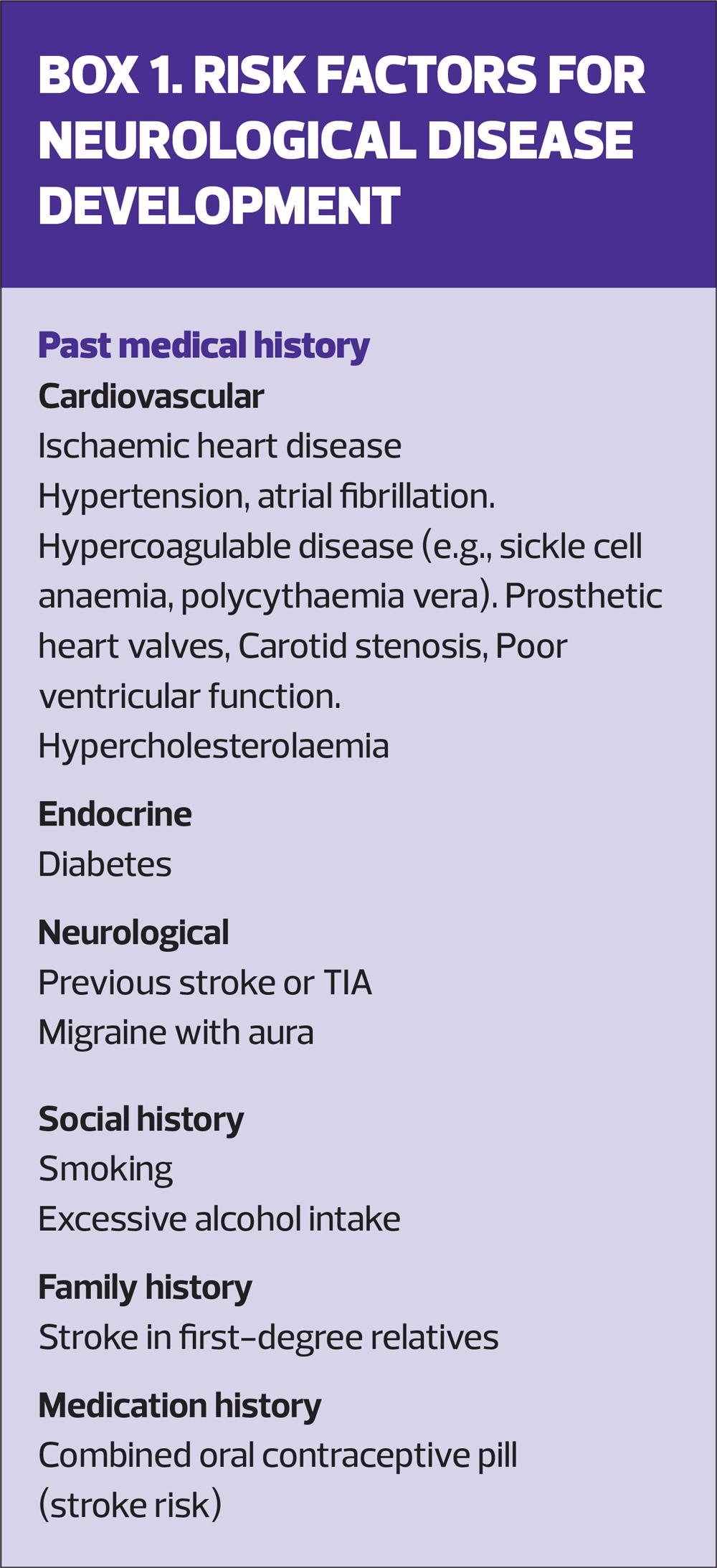

Reviewing the patient’s records is a sound basis for assessment of neurological risk factors and can contribute valuable information.7 Patients may not realise that ongoing medical issues may be pertinent to a neurological history, or report them, (Box 1) and they may not appreciate that some prescribed drugs can have adverse effects on the neurological system. For example, peripheral neuropathy is commonly related to medications such as statins, levodopa, metronidazole and nitrofurantoin, and dystonia is associated with common antipsychotics and antiemetics.8,9

Gathering information

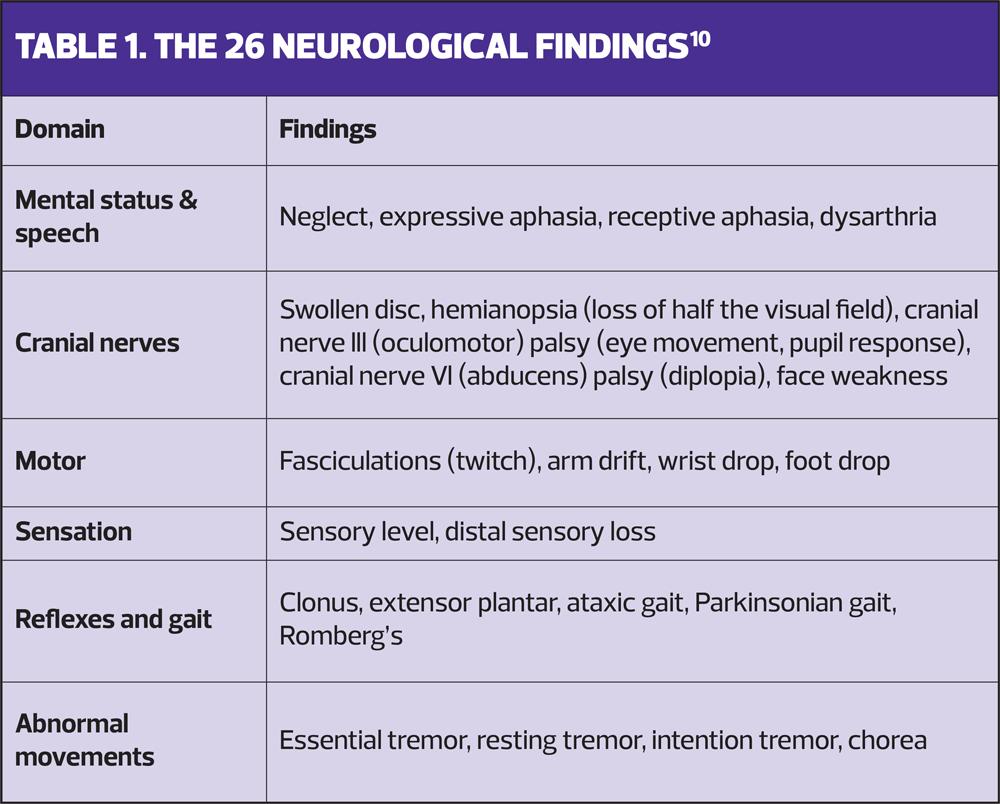

Commence assessment as the patient enters the room, observing for general habitus, speech, facial weakness, tremor, and walking gait, which comprise five of the 26 neurological findings (Table 1).10 This offers key information about debilitating neurological function which influences patient autonomy in activities of daily living. For example, gait disturbance is frequently found in Parkinson’s disease (festinating gait), stroke, alcohol excess (ataxic gait), motor neurone disease and small vessel dementia (disorganised, slow gait). Advanced age, dementia, alcohol abuse, central nervous system drugs and some chemotherapeutics are risk factors for gait disorders.5 Sudden onset, or rapidly deteriorating ataxic gait (unsteady, staggering, uncoordinated) requires urgent referral for exclusion of stroke.6

A calm friendly approach develops rapport, permits patients time to describe their symptoms, and enables assessment of physical and psychological distress.11 Listening to the patient indicates the impact of the problem on their life: neurological disease can be incapacitating. However, confusion, syncope, and loss of consciousness prevent patients giving a precise history, so input from relatives or carers can be vital.8

A chronological symptom assessment, what happened first and subsequent development of other symptoms, is essential.9 Sudden onset implies acute vascular causes whereas gradual onset implies degenerative, demyelination and neoplastic origins.12 Chronic neurological conditions have intermittent, unpredictable onset and course, as in epilepsy, or a stable course, as in cerebral palsy.12

Prevalence of neurological conditions sharply increases with advancing age, so patients are also vulnerable to comorbid risks, such as falls.

FOCUSING ON SYMPTOMS

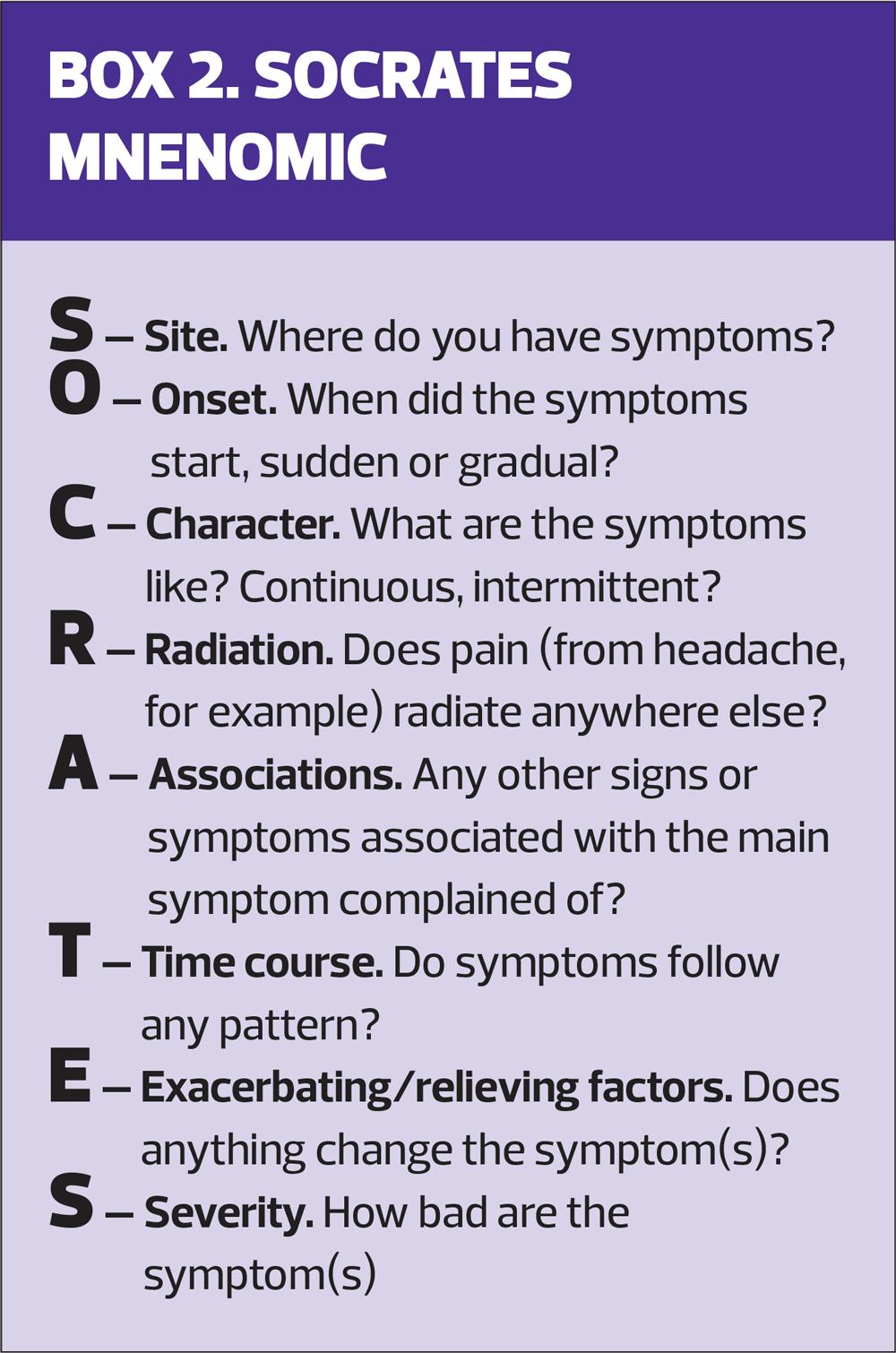

Focusing closed questions upon crucial neurological symptoms will help define differential diagnoses.13 The SOCRATES mnemonic (Box 2), usually used to explore pain symptoms, offers a comprehensive structure which aids differentiation of significant symptoms.

Headache is a common complaint associated with substantial loss of work, school days, and healthcare costs.14 Differentiation between common and rare causes is challenging, so meticulous investigation of this, or any other symptom, exposes concerning features. Migraine headache is generally unilateral in site, moderate to severe, characterised as throbbing, and often preceded by associated features like tiredness, yawning (72-84%), aura (visual disturbance, light sensitivity), nausea and vomiting.15 Pain exacerbates with physical activity ending in postdrome tiredness and cognitive difficulties.14 Migraine symptoms become undistinguished in older patients.16 Migraine may be relatively common, but it remains imperative to exclude associated features which indicate more sinister pathology – brain tumour headaches are commonly characterised as ‘tension’ like, or akin to migraine.17 A history of increasing severity, frequency, or associated features is a cause for concern.5

Other symptoms

Transient loss of consciousness (blackout) featuring limb-jerking, tongue biting, confusion, or disorientation are suggestive of epileptic seizures.18 The episode is less likely to be related to epilepsy if there have been no prodomal symptoms, or these are resolved by sitting or lying down; there is sweating before or pallor during the episode, or it was preceded by prolonged standing. Consider orthostatic hypotension.18

Palpitations related to atrial fibrillation are a risk factor for stroke.19

Paraesthesia also features in stroke, TIA, cauda equina syndrome, demyelinating disorders, and systemic diseases such as diabetes.19

Nausea and vomiting can indicate simple migraine, or raised intracranial pressure secondary to masses, cerebrospinal fluid disorders and posterior circulation stroke.20

Dizziness is common in vestibular dysfunction, vestibular migraine,21 posterior circulation stroke, functional disorders, and hypoglycaemia.6

Fever signals infective causes. Intravenous drug users are susceptible to septic emboli or abscess, as are patients with infective endocarditis.22 In febrile children under 5 years, or children over 5 with headache, suspect meningitis.24 Symptom onset is rapid with associated irritability, loss of appetite, nausea, vomiting, sore throat or coryza lasting 4-8 hours. Symptoms may progress swiftly to leg pain, abnormal skin colour, cold peripheries, thirst, dyspnoea, and confusion. Petechial rash, neck stiffness, and photophobia occur later, 12-15 hours from onset.23

Confusion may be a symptom of stroke (or TIA), Parkinson’s disease, seizures or dementia, but it may also be caused by medication, dehydration, or hypoglycaemia. Establish a level by asking three simple questions of the patient; their age, the current month, and what they think your role to be. These quickly assess orientation, understanding, and speech while a baseline of normal cognition might be sought from a relative or carer for comparison.9

Timing

The timing of symptoms is significant as differentiation between stroke and transient ischaemic attack (TIA) determines management. A history of similar symptoms that resolved may indicate preceding TIAs. The Face, Arms, Speech, Test reliably increases stroke recognition.24 Novel symptoms of altered spatial perception, uncoordinated limbs, disorientation, visual disturbance, and awareness of something wrong, but not what, help differentiate TIA from stroke. Classically, stroke presents as weakness ranging from limb clumsiness to sudden complete paralysis associated with decreasing conscious level.7

Sudden onset of severe or ‘thunderclap’ headache associated with head injury, vomiting or focal neurology in patients under 60 years, warrants immediate referral to exclude acute subarachnoid haemorrhage (aSAH), which accounts for 5% of all cerebrovascular events. Risk factors include family history of aSAH in a first degree relative, hypertension, coagulopathies, and vascular malformations.25

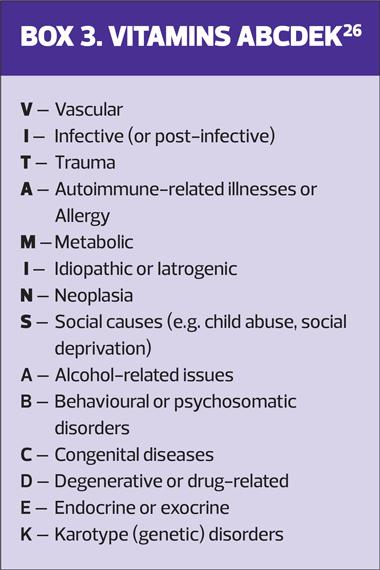

A robust history may identify a single cause, or diffuse causes affecting the central and peripheral nervous system, and directs examination focus to the most relevant aspects, however, remember to exclude systemic diseases.8 Clinical reasoning tools aid differentiation in neurological assessment, and the VITAMINS ABCDEK mnemonic is a practical way to cover all possible causes of illness (Box 3).26

THE EXAMINATION

The aim of initial assessment and examination in primary care is to recognise when a finding is abnormal and then to act accordingly, not specifically to make a diagnosis. This provides both clinician and patient with some reassurance, or to determine the need for referral, to a GP or into secondary care.

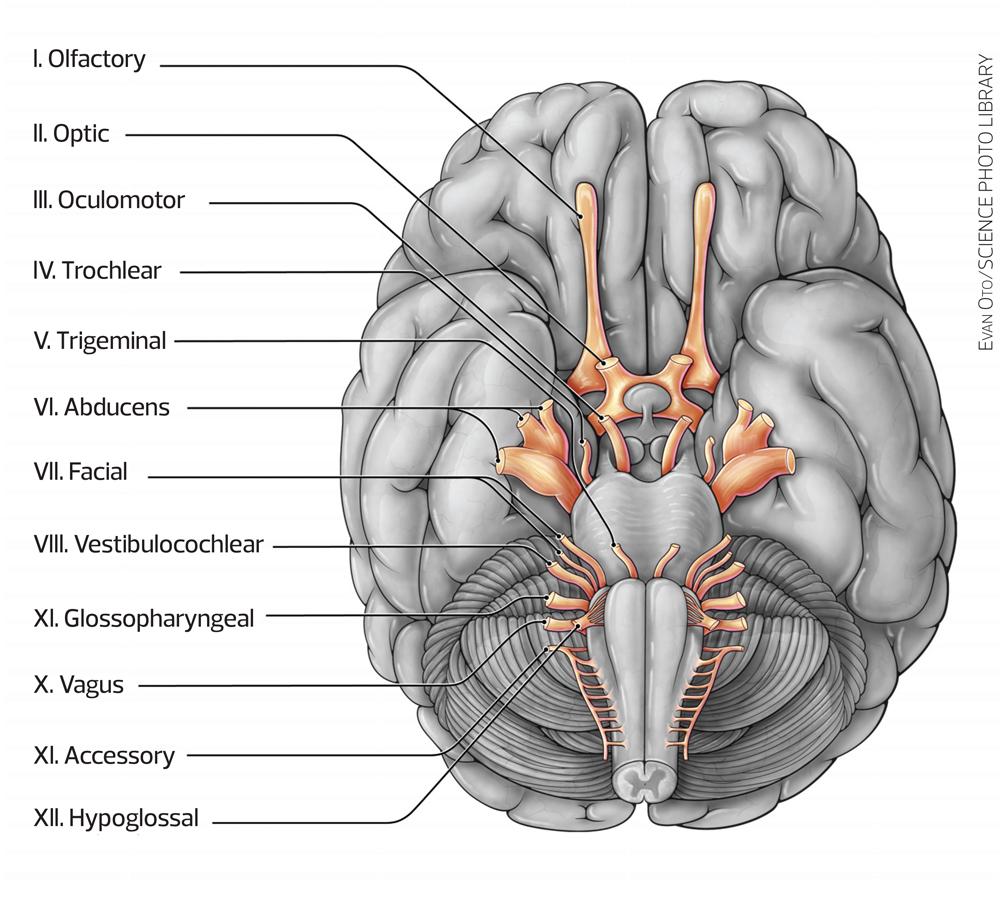

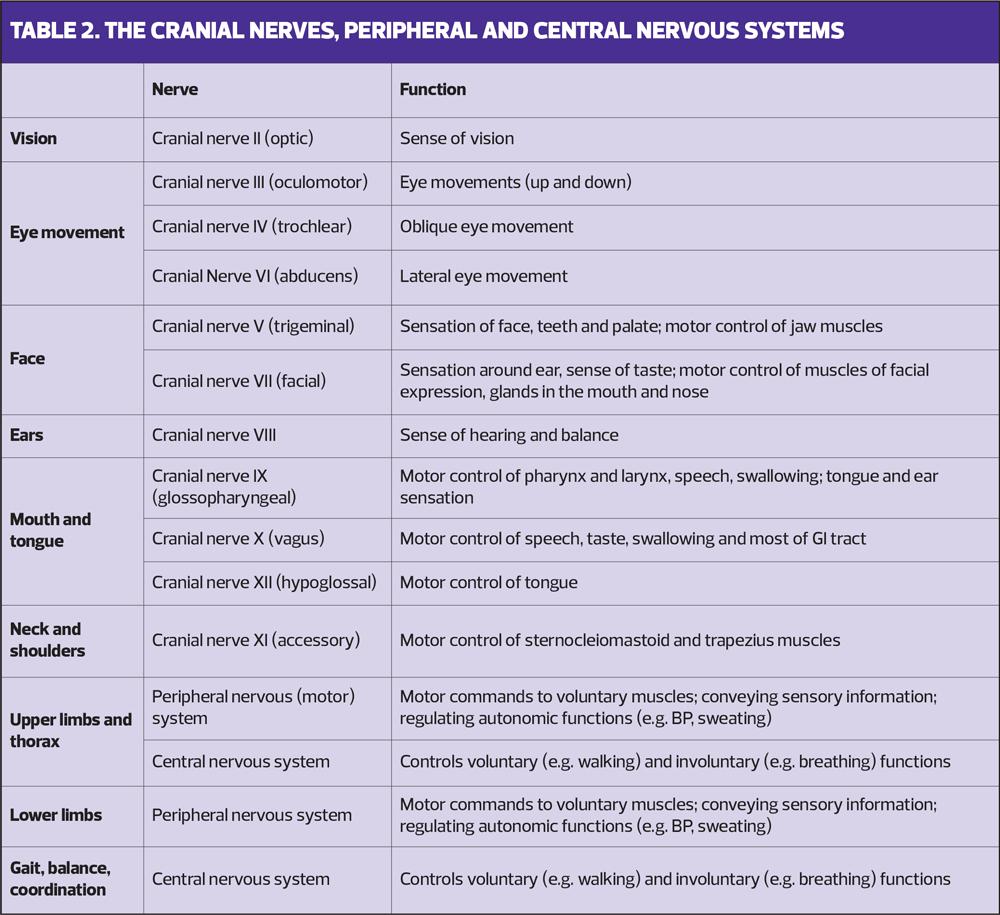

An understanding of the cranial nerves, the central nervous and peripheral nervous systems and their functions will inform your examination (Table 2).

General inspection

As described above, the examination starts as the patient enters the consulting room: observe their posture, gait, and movement. Take note of any walking aids, and assess their general awareness.

Assess mental status

Assess the patient’s alertness – are they awake, alert and oriented (AAOx3 ) to person, place and time? Ask the patient to state their age, the current month and what they think your role to be.

Assess for speech disturbance

Ask patient to name objects, repeat words

Vision

Ask about double vision. Inspect for nystagmus, ptosis, ophthalmoplegia and, using a pen torch, check the pupils with pen torch for size, shape, equal movement, response to light, accommodation and convergence.

Measure visual acuity using a Snellen chart at 6m or 3m; consider use of pin hole if vision is poor. Assess visual fields: sit in front of the patient, 1m apart. Ask the patient to cover their right eye with their hand, while you cover the left eye, mirroring the patient. Ask the patient to look at your nose and position your fingers at an equal distance between you. Flash one or two fingers in each quarter of vision comparing the patients fields to your own.

Eye movements

Draw an H in the air, and ask the patient to follow, observing eye movements in six directions of gaze.

Face

Ask the patient to close their eyes and assess facial sensation on both sides of forehead, cheek, and jaw with cotton wool. Ask them to clench their teeth together and resist you trying to open their mouth. Ask the patient to show their teeth, raise their eyebrows, resist eye opening. Get them to puff out cheeks holding them puffed out while you press both cheeks. Test corneal reflex with a piece of cotton wool.

Ears

Assess hearing using whispered voice bilaterally.

If impaired, Rinne or Weber tests can be used to assess bone and air conduction using a tuning fork.

Mouth and tongue

Ask the patient to stick out their tongue and move it from side-to-side checking for deviation. Ask about voice changes, swallowing difficulties. Ask the patient to cough, swallow, and test their gag reflex.

Ask patient to say ‘ah’ looking for symmetrical movement of soft palate, deviation of the uvula, tongue wasting. Ask patient to stick out tongue looking for deviation. Place your finger on each cheek and ask patient to push tongue against it assessing and comparing power.

Neck and shoulders

Assess shoulder shrug power by asking the patient to resist pressure, and check for power in rotation of the head against resistance.

Upper limbs and thorax

Inspect upper body muscle bulk for wasting, fasciculations, disuse atrophy, contractures.

Assess body position during rest and movement.

Assess tone in arms: ask the patient to ‘go floppy’ while you passively flex and extend the shoulder, elbow, and wrists, looking for increased spasticity or rigidity.

Assess power in resisted flexion and extension of elbow and wrist. Test finger grip strength, power in finger abduction and thumb opposition.

Look for patterns e.g., extensors weaker than flexors in arms is an upper lesion sign.

Assess sensation with light touch (cotton wool) comparing left to right symmetrically. Ask patient to close their eyes and demonstrate normal sensation on their sternum first. If sensation is absent consider assessing with pain, temperature, joint position sense and vibration.

Check tendon reflexes in the biceps (C5/6), triceps (C6/7), and wrist supinator (C5/6). Are they brisk, reduced, or absent?

Gait, balance and coordination

Assess cerebellar function through heel to shin test, or heel toe walking. Assess gait if not seen previously.

Assess balance through Romberg’s test. Falling without trying to correct is abnormal: a positive Romberg’s test indicates sensory ataxia.

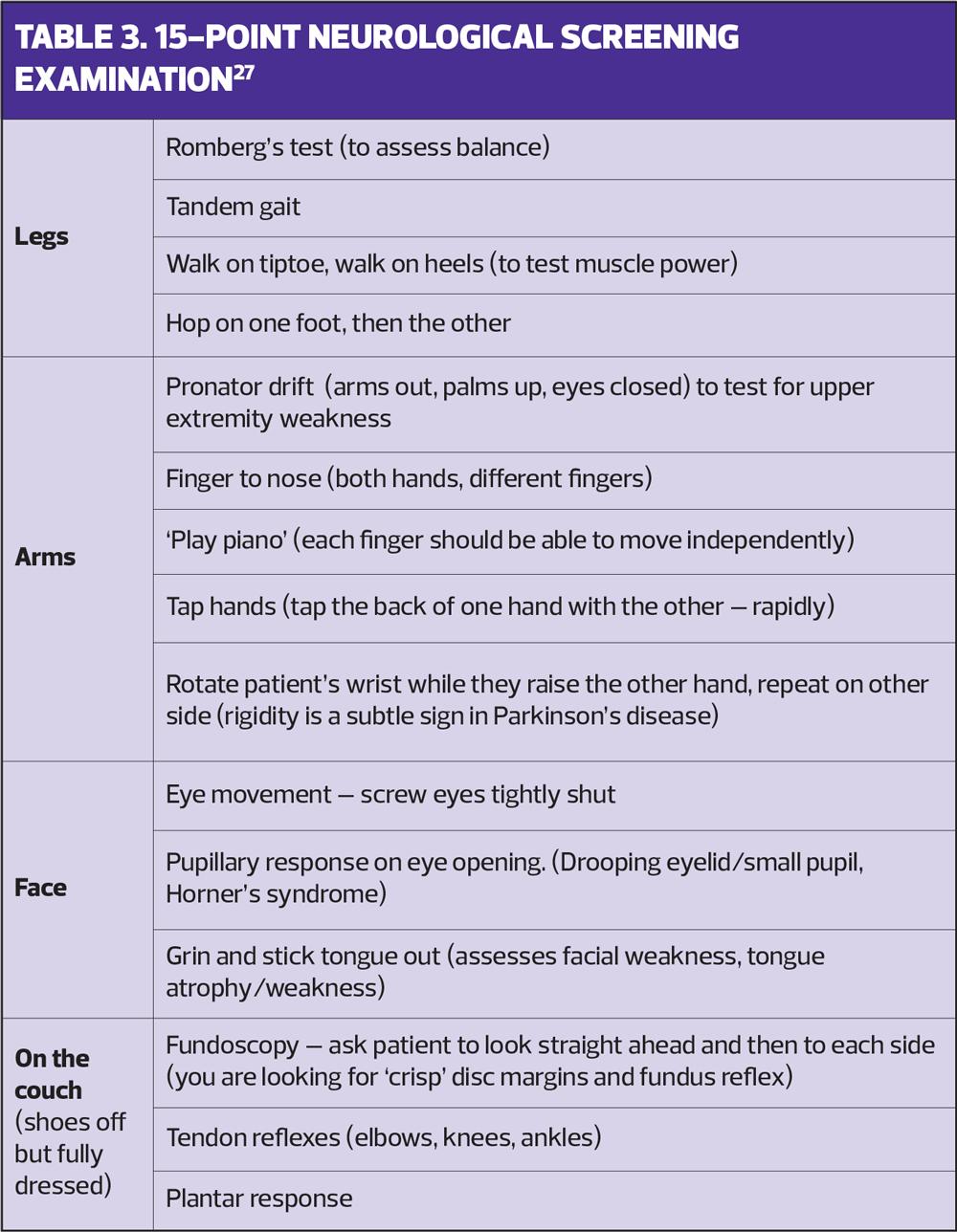

A full neurological examination may not be feasible in a short consultation when a patient presents with a suspected neurological condition,27 but it is possible to carry out a ‘quick’ 15-point screening examination (Table 3), following which you can undertake more focused examinations (See resources) to target specific diagnoses as suggested by the patient’s history, or refer the patient for further assessment.

EXPLANATION AND PLANNING

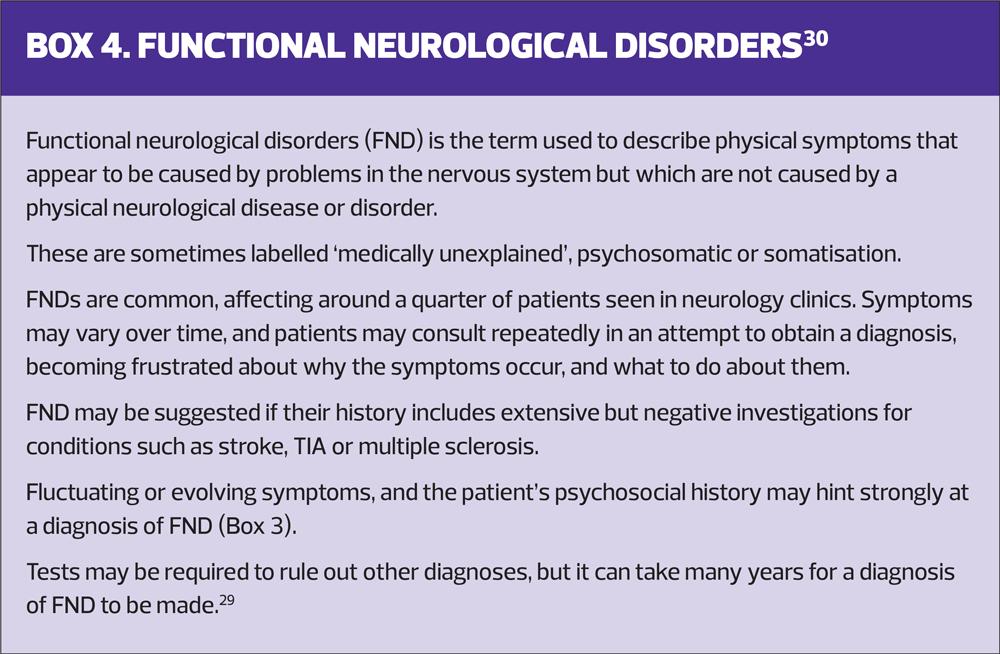

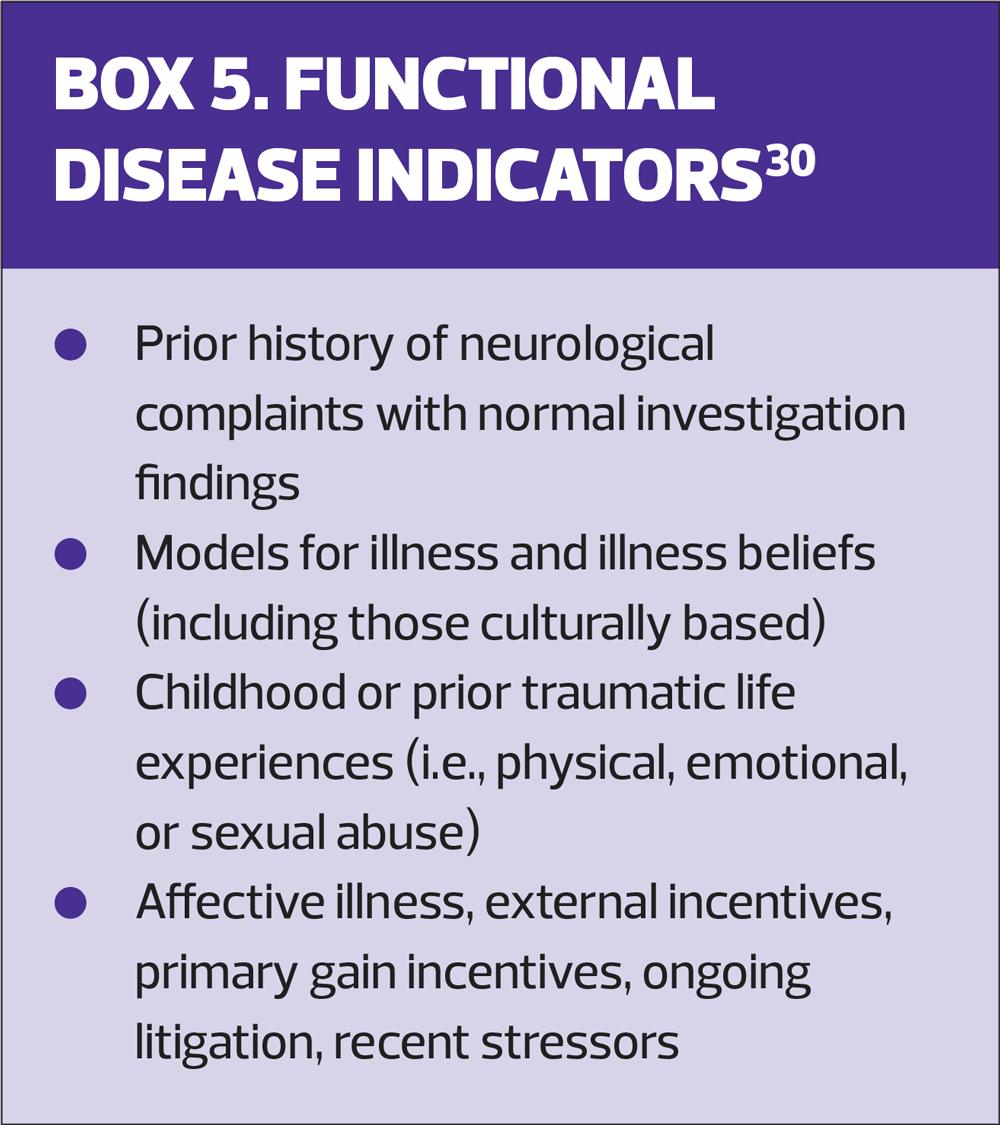

If a differential diagnosis is unclear, recapture the history, review systems looking for neurological symptoms, or summarise information the patient has presented.8 This reduces misinterpretations and establishes the impact of the problem: pre-empting a neurological diagnosis could cause unnecessary distress to the patient, as it could mark the preliminary stages of dependence, cognitive dysfunction, and shortened lifespan, poignant aspects which should be addressed.28 Sensitivity is needed if the patient is a risk to themselves or others, or in assessing functional causes (Boxes 4,5).

CLOSING THE SESSION

Neurological symptoms require clear safety nets signposting actions if symptoms worsen, change, or there is neurological deterioration.29 Patients may expect referral to a specialist, a CT scan or MRI to alleviate concerns. In the absence of reliable examination findings, a strong history justifies referral to a specialist.5

CONCLUSION

Comprehensive neurological assessment by GPNs is possible using structural tools, aids and a simplified approach to examination. GPNs would benefit from undertaking a health assessment module, either as a single module, or as part of an Advanced Clinical Practice masters degree, to augment practical clinical knowledge.

REFERENCES

1. Neurological Alliance. Issues affecting neurology services. Neurological Alliance briefing; 2016. https://www.neural.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/2016-04-facts-for-neurology.pdf

2. Feigin VL, et al. Global, regional, and national burden of neurological disorders, 1990–2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet Neurol 2019;18(5):459–480

3. Coster S, Watkins M, Norman IJ. What is the impact of professional nursing on patients’ outcomes globally? An overview of research evidence. Int J Nurs Studies 2018; 78:76–83

4. Zasler ND. Validity assessment and the neurological physical examination. NeuroRehabilitation 2015;36(4):401–413

5. Nicholl DJ. Are the skills of neurological assessment in need of resuscitation? Acute Medicine 2015;13(4): 178-180.

6. NICE CG127. Suspected neurological conditions: recognition and referral; 2019. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng127/

7. Kirkpatrick S, Locock L, Giles MF, Lasserson DS. Non-focal neurological symptoms associated with classical presentations of transient ischaemic attack: qualitative analysis of interviews with patients. PloS one 2013;8(6): https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0066351)

8. Jones MR, Urits I, Wold J, et al. Drug-induced peripheral neuropathy: a narrative review. Curr Clin Pharmacol 2020;15(1):38-48

9. Kennedy A, Zakaria R. (2016). Taking a neurological history. Medicine 2016;44(8):459–463. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mpmed.2016.05.003

10. Hickey JV. The Clinical Practice of Neurological and Neurosurgical Nursing. LWW, Philadelphia, PA;2014

11. Gask L, Usherwood T. ABC of psychological medicine. The consultation. BMJ 2002;324(7353), 1567–1569. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.324.7353.1567

12. NHS England. Neurological conditions; 2022. https://www.england.nhs.uk/ourwork/clinical-policy/ltc/our-work-on-long-term-conditions/neurological/

13. Izumi-Richards N, Simon C. (2013). Neurological Assessment. InnovAiT 2013;6(7):405–415 https://doi.org/10.1177/1755738013488013

14. Stovner LJ, Nichols E, Steiner TJ, et al. Global, regional, and national burden of migraine and tension-type headache, 1990–2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet Neurol 2018;17(11):954-976. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1474-4422(18)30322-3.

15. Dach F. Migraine pathophysiology, clinical correlates. J Neurol Sciences 2021;429(Suppl). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jns.2021.117898

16. Straube A, Andreou AP. Primary headaches during lifespan. J Headache Pain 2019;20: 35 https://doi.org/10.1186/s10194-019-0985-0

17. Ozawa M, Brennan PM, Zienius K, et al. Symptoms in primary care with time to diagnosis of brain tumours. Family Practice 2018;35(5):551–558 https://doi.org/10.1093/fampra/cmx139

18. NICE CG109. Transient loss of consciousness ('blackouts') in over 16s; 2010. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg109

19. Powers WJ, Rabinstein AA, Ackerson T, et al. Guidelines for the early management of patients with acute ischemic stroke: 2019 update. Stroke 2019;50(12), e344-e418

20. Dunn LT. Raised Intracranial Pressure. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2002;73: i23-i27. https://jnnp.bmj.com/content/73/suppl_1/i23.info

21. Yardley l, Barker F, Muller I, et al. Clinical and cost effectiveness of booklet based vestibular rehabilitation for chronic dizziness in primary care: single blind, parallel group, pragmatic, randomised controlled trial. BMJ 2012;344(7860):395–13. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.e2237

22. Elsaghir H, Al Khalili Y. Septic Emboli; 2022. In Stat Pearls. StatPearls Publishing. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK549827/

23. Thompson MJ, Ninis N, Perera R, et al. Clinical recognition of meningococcal disease in children and adolescents. Lancet 2006;367(9508), 397–403. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(06)67932-4

24. NICE NG128. Stroke and transient ischaemic attack in over 16s: diagnosis and initial management; 2019. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng128

25. National Confidential Enquiry into Patient Outcome and Death, (NCEPOD, 2013) Managing the Flow? A review of the care received by patients who were diagnosed with an aneurysmal subarachnoid haemorrhage. https://www.ncepod.org.uk/2013report2/downloads/ManagingTheFlow_FullReport.pdf

26. Zabidi-Hussin ZA. Practical ways of creating differential diagnoses through an expanded VITAMINSABCDEK mnemonic. Adv Med Educ Pract 2016;7:247-8

27. BMJ Learning module. Quick neurological exam for primary care. https://new-learning.bmj.com/course/10060869

28. Ogden J, Bavalia K, Bull M. “I want more time with my doctor”: a quantitative study of time and the consultation. Fam Pract 2004; 21:479–483.

29. Richards S, Boiling B. Neurological Assessment: Assessing Sensory Function. Nursing Practice and Skill 2016; https://www.ebscohost.com/promoMaterials/NPS_Neurological_Assessment.pdf

30. Sheffield Teaching Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust. Functional Neurological Disorders. https://www.sth.nhs.uk/services/a-z-of-services?id=115&page=293

31. Cock HR, Edwards MJ. Functional neurological disorders: acute presentations and management. Clin Med 2018;18(5):414–417. https://doi.org/10.7861/clinmedicine.18-5-414

Related articles

View all Articles