Bite-sized learning: Understanding RA

Una O’Connor RGN MSc FHEA, Operational Manager, Learn with Nurses | Michaela Nuttall RGN MSc, Founder & Director, Learn with Nurses | Joanne Haws RN MSc, Clinical Director, Learn with Nurses

Practice Nurse 2026;56(1):10-11

Rheumatoid arthritis is a major cause of pain and disability, but diagnostic delay is common and many patients miss the critical window of opportunity for initiation of disease modifying drugs which would slow progression and improve rates of remission

INTRODUCTION

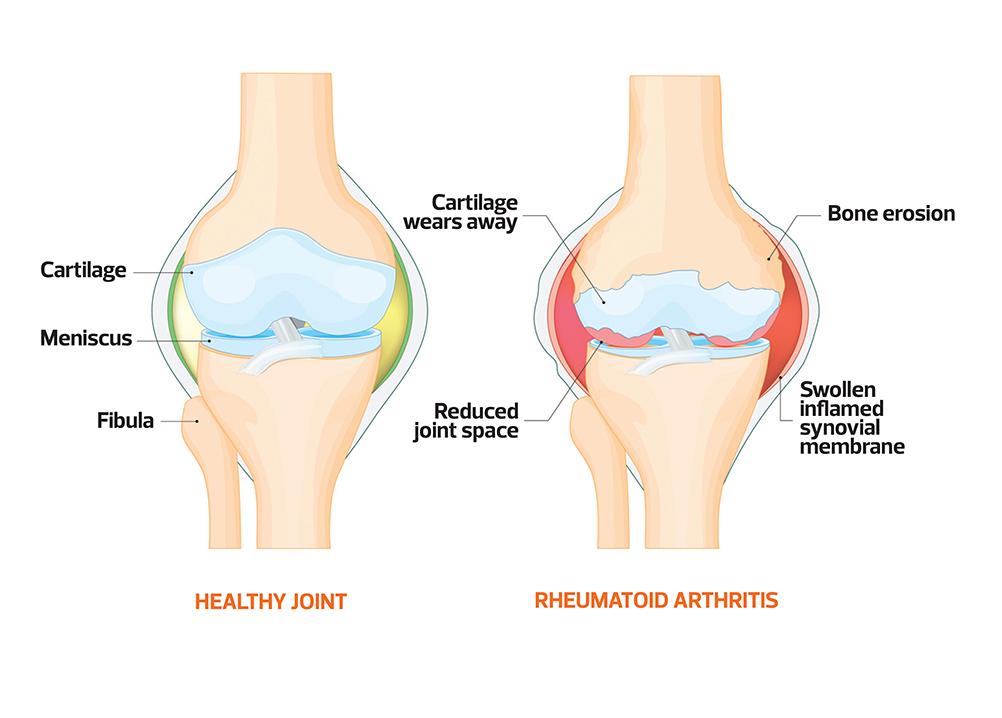

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is a chronic, systemic autoimmune disease that is more than a joint disorder. It is characterised by persistent synovial inflammation, symmetrical polyarthritis and progressive joint damage. Although it most commonly affects the small joints of the hands and feet, larger joints and multiple extra-articular organs (including the lungs, cardiovascular system and eyes) may also be involved. If untreated, RA leads to pain, deformity, functional impairment and increased morbidity and mortality. Diagnosis is based on clinical features, serological markers (such as rheumatoid factor and anti-CCP antibodies) and imaging. Early recognition and prompt initiation of disease-modifying therapy are crucial to limiting long-term disability and systemic complications.

WHAT’S THE PROBLEM?

RA affects approximately 1% of the UK population, with an annual incidence of around 3–4 per 10,000 women and 1–2 per 10,000 men.1 Despite therapeutic advances, RA remains a major cause of pain, disability and excess mortality. Diagnostic delay is common; many patients still miss the 3-month ‘window of opportunity’ for disease-modifying antirheumatic drug (DMARD) initiation, associated with greater radiographic progression and lower remission rates.2 A substantial subgroup meets criteria for difficult-to-treat RA, with persistent active disease despite multiple conventional synthetic (cs) DMARDs and biologics.3 RA also confers 1.5–2-fold higher cardiovascular risk and substantial indirect economic costs.1,4

DETECTION

Early detection of rheumatoid arthritis is essential to prevent irreversible joint damage and systemic complications. Clinicians should maintain a high index of suspicion in adults with persistent joint pain, swelling or morning stiffness ≥60 minutes, particularly when small joints of the hands or feet are involved for >6 weeks. Simple clinical tests, such as squeezing metacarpohalangeal (MCP) or metatarsophalangeal (MTP) joints, can help elicit early synovitis. NICE guideline NG100 recommends urgent rheumatology referral when inflammatory arthritis is suspected to enable timely diagnostic confirmation and treatment.1

DIAGNOSIS

Diagnosis of RA is primarily clinical, supported by serology and imaging. Persistent synovitis in multiple small joints, prolonged morning stiffness and symmetrical involvement for more than six weeks should raise suspicion. Rheumatoid factor and anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide (CCP) antibodies support the diagnosis and help stratify prognosis; erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) and c-reactive protein (CRP) may be elevated but can also be normal. Ultrasound or MRI can detect synovitis and early erosions. Assessment should follow NICE guidance on the referral, diagnosis and investigation of rheumatoid arthritis in adults (NICE guideline NG100).1

MANAGEMENT

Management of rheumatoid arthritis focuses on rapid suppression of inflammation and prevention of structural joint damage through a treat-to-target strategy. (DMARDs) — medications that alter the underlying disease process rather than simply treating symptoms — form the foundation of therapy. NICE NG100 recommends early initiation of a csDMARD, most commonly methotrexate, ideally commenced within 3 months of symptom onset. Short-term glucocorticoids may be used as bridging therapy to control symptoms while DMARDs take effect.

If treatment targets are not achieved, therapy should be escalated through combination csDMARDs or the introduction of biologic DMARDs. Targeted synthetic DMARDs include Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitors, oral agents that block intracellular signalling pathways involved in inflammation and immune activation, and are available for patients with inadequate response to at least one biologic, with careful consideration of cardiovascular and thrombotic risk.

REVIEW

Regular review is essential to maintain disease control and minimise long-term damage. Patients with active RA should be assessed frequently (often every 1–3 months) using validated composite measures such as DAS28 to guide treat-to-target adjustments. Review should encompass affected joint counts, patient-reported outcomes, acute-phase reactants and functional status, alongside systematic monitoring for DMARD and biologic toxicity (blood counts, liver and renal function) and infection risk. Once stable low disease activity or remission is achieved, review intervals may be extended, but ongoing surveillance for flares, cardiovascular risk factors, osteoporosis, mood disorders and treatment adherence remains crucial. Shared decision-making at each review helps optimise therapy and support effective self-management.

References

- NICE NG100. Rheumatoid arthritis in adults: management; 2018 (updated 2020). https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng100 (https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng100)

- Siddle HJ, Bradley SH, Mankia K, Emery P, Hodgson R. Opportunities and challenges in early diagnosis of rheumatoid arthritis in general practice. Br J Gen Pract 2023;73(729):152–154.

- Nagy G, Roodenrijs NMT, Welsing PMJ, et al. EULAR definition of difficult-to-treat rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 2021;80(1):31–35.

- Johri N, Varshney S, Gandha S, et al. Association of cardiovascular risks in rheumatoid arthritis patients: management, treatment and future perspectives. Health Sci Rep 2023;6(2):e100108.

Related articles

View all Articles