Preventing suicide: the role of primary care

Dr Sheila Hardy

Dr Sheila Hardy

PhD, MSc, BSc (Hons), NISP, RMN, RGN

Mental health trainer, Practice Nurse Educator

Charlie Waller Trust

Practice Nurse 2021;51(7):18-21

Nine in ten people who commit suicide visit their general practice in the year before their death but only one in four was in contact with mental health services. Is there more that can be done in primary care to reduce suicide risk?

General practice nurses may be concerned that they would not be able to help someone who is contemplating suicide. This is not the case: by asking a few simple questions, displaying empathy, and making sure they get to see the person who can get them the help they need, a life could be saved.

This article aims to provide you with the information you need to help reduce the risk of suicide, including:

- How suicide is defined

- Current rates of suicide

- How primary care health professionals can reduce suicide risk

WHAT IS SUICIDE?

Suicide is defined by the American Psychiatric Association as the act of killing oneself, usually as a consequence of depression or another mental illness.1 It has been argued, however, that although suicidal behaviour often occurs due to mental illness, it is not always the case.2 Just half of those who died by suicide were formerly referred to mental health services,3 and it has been reported that 37% of patients who had attended primary care and then died by suicide never received a diagnosis of mental illness.4 This maybe because suicides can occur spontaneously in times of crisis when the person is unable to cope with stress,5 which can be caused by monetary problems, relationship issues, or chronic pain and illness.

There are high rates of suicide among people who have endured conflict, disaster, violence, abuse, loss and a sense of isolation; and among those who experience discrimination (refugees and migrants; indigenous peoples; lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, intersex [LGBTI] persons; and prisoners).5 One per cent of people who died by suicide in the UK between 2006 and 2016 were from a Black and Minority Ethnic (BAME) group.6

In England and Wales, suicide is verified by a coroner, who is either medically or legally qualified, following an inquest. Until 2018, a verdict of suicide was only given if the evidence of suicidal intent met the criminal standard of proof, beyond reasonable doubt.7 Since then, what was once called the verdict is now the conclusion; the Court of Appeal in England and Wales ruled that the standard of proof required for a suicide conclusion should be the civil standard, and therefore will be reached on the balance of probabilities. This lowering of the threshold could lead to an increase in deaths recorded as suicide.8

A coroner’s conclusion is sent to the Office for National Statistics (ONS) so that the suicide can be recorded in national statistics, and notified to the National Confidential Inquiry (NCI) which uses the data to monitor factors such as contact with services in the year prior to death.

Rates of suicide

The ONS 2020 report9 states that there were 5,691 suicides in England and Wales. The male suicide rate of 16.9 deaths per 100,000 in 2019 is the highest since the year 2000 and the female rate of 5.3 deaths per 100,000 is the highest since 2004. Men are more likely than women to respond to stress by taking risks or misusing alcohol and drugs this in turn increases suicide risk.9

Males aged 45 to 49 years had the highest age-specific suicide rate (25.5 deaths per 100,000); for females, the age group with the highest rate was 50 to 54 years at 7.4 deaths per 100,000.9 Some experts argue that this is because middle-aged people are facing more mental health problems and unhappiness compared to younger and older people,10 but death rates by suicide among the under 25s have also increased, particularly in females aged between 10 and 24 years (3.1 deaths per 100,000).9

The most common method of suicide in England and Wales is still by hanging, accounting for 61.7% of all suicides among males and 46.7% of all suicides among females.9

Preventing suicide

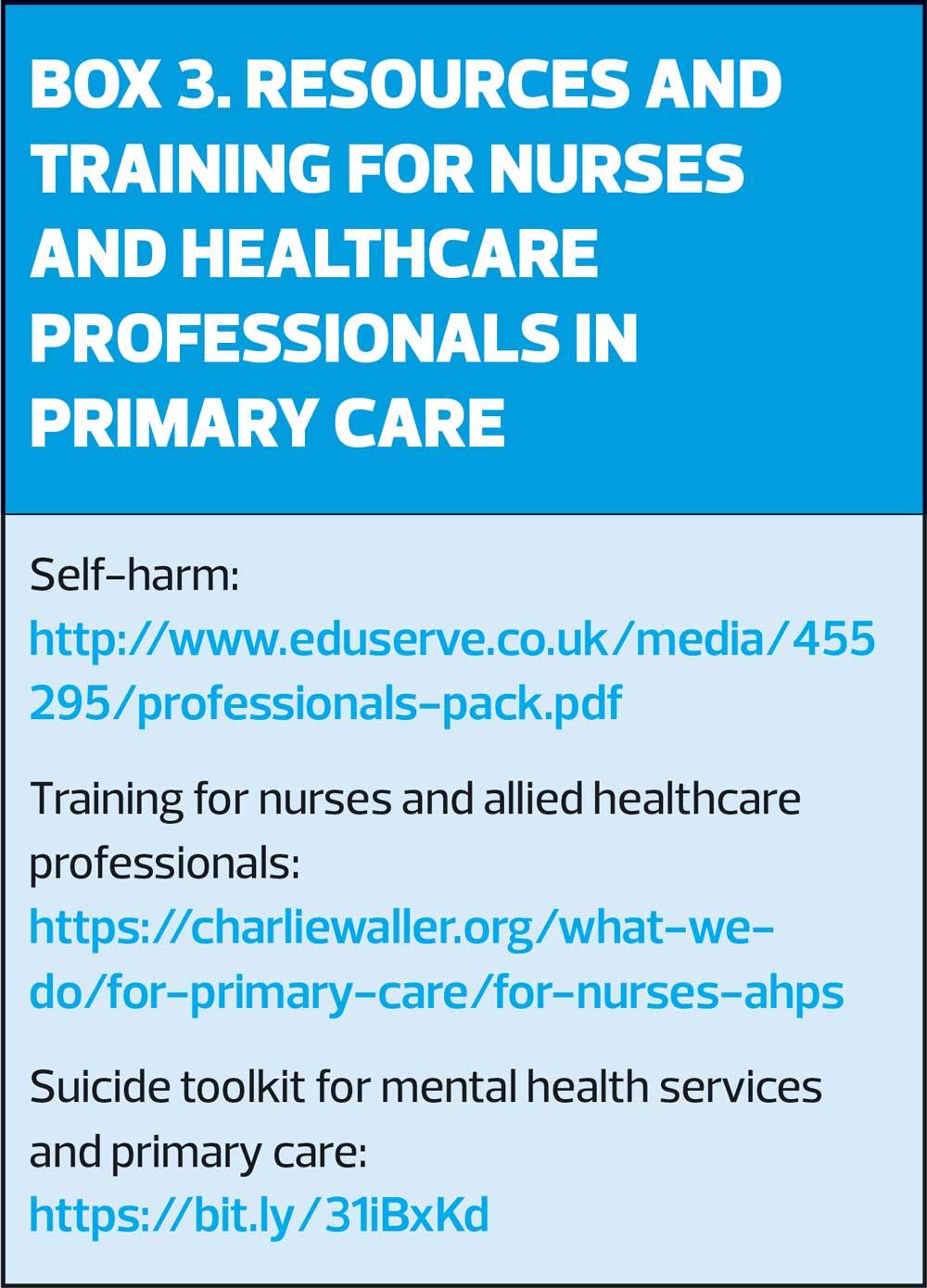

Improving the mental health of the whole population is one way of reducing suicide. In their report, ‘No Health Without Mental Health’11 the Government recommends a variety of evidence-based treatments and interventions to prevent people from developing mental health problems. There is evidence to suggest that suicide awareness training for primary care staff can have an impact at a population level intervention to prevent suicide.12 Local statistics for suicide can be found by looking online at the Suicide Prevention Profile hosted by Public Health England.13

Recognition of suicide risk

Over 90% of people whose death was due to suicide, had visited their primary care centre in the year prior to death4 and only a quarter of them had been in contact with mental health services in the year prior to death.3

In 2019, the Department of Health published its second suicide prevention strategy.14 It emphasises how important it is for services, communities, families and society to work together to help prevent suicides. It highlights that primary health care workers need to be skilled and proactive in identifying and intervening with patients showing signs of suicidal behaviour as they are often the first to see those who are experiencing distress or suicidal thoughts.

Leavey et al conducted interviews with relatives and friends bereaved by suicide and with GPs who had experienced the suicide of patients.15 They found failures in the recognition and management of suicidal patients, and structural inadequacies in service provision. Specialists have recommended that suicide awareness training programmes for primary care should be put in place to improve diagnosis and signposting to services.16

People living with a long-term physical condition (physical illness, disability and chronic pain) are more likely to have depression. Often this goes undiagnosed and therefore untreated, increasing the risk of suicide.17 Young people who attend primary care and divulge they are self-harming have a high risk of suicide.18 Self-harm occurs more rarely in older people but those who do have a high risk of suicide; experts advocate improving the clinical management of this group, suggesting the need for referral to mental health specialists.19

THE ROLE OF HEALTHCARE PROFESSIONALS IN PRIMARY CARE

Guidance for healthcare professionals to deliver safer care for people with depression in primary care has been offered by the NCI,6 which suggests having systems in place to:

- Make sure that patients who have a long-term physical health condition are assessed and monitored for depression and risk of suicide

- Guarantee that patients with indicators of risk (such as frequent consultations, multiple psychotropic drugs and specific drug combinations) are assessed and considered for referral to specialist mental health services

- Enable GPs to review care with mental health staff

Practice nurses and primary healthcare staff may reduce the risk of suicide if they recognise depression, ask the appropriate questions about intention to harm or kill oneself, provide lifestyle advice, and signpost to support or refer for treatment as appropriate.

Recognising depression

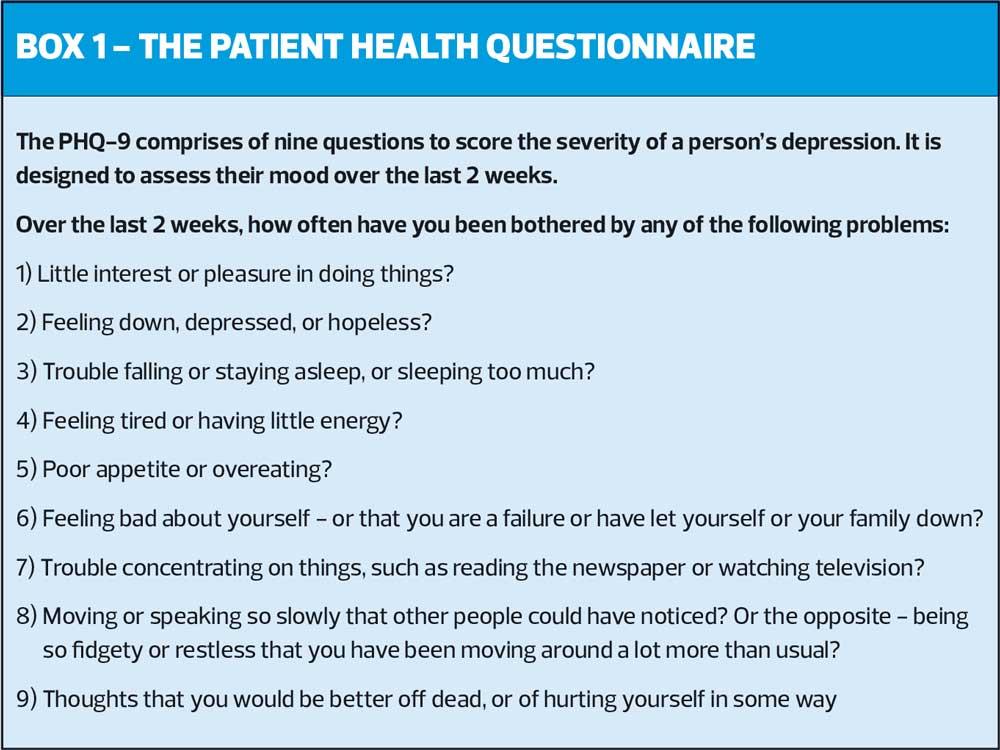

Practice nurses and primary healthcare staff should consider screening for depression in people in the at-risk groups described above and assessing those presenting with symptoms. There are two screening questions available.20 The person simply answers ‘yes’ or ‘no’. The questions are:

- 'During the last month have you often been bothered by feeling down, depressed, or hopeless?'

- 'During the last month have you often been bothered by having little interest or pleasure in doing things?'

An answer of ‘No’ to the questions indicates that the person is unlikely to have depression, but they should be given the option of coming back to see a healthcare professional should they change their mind. An answer of ‘Yes’ should prompt a more detailed assessment, using the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) (Box 1). If a person attends and volunteers that they are feeling down or depressed, they can be assessed with the PHQ-9 and there is no need to use the screening questions.

Appropriate questions about intention to harm or kill oneself

When a person presents with possible depression, they should always be asked directly about suicidal ideation and intent.21 Some people are concerned by asking these questions that they may put the idea of suicide in the person’s mind; but talking openly about suicide actually decreases the probability of the person acting on their feelings. Ask:

- Have you made a suicide attempt in the past?

- Do you think that life is not worth living?

- Do you think about harming or killing yourself?

- Have you got a plan to kill yourself?

- Do you aim to carry out this plan?

- What would stop (or is stopping) you from carrying out your plan?

No suicidal ideation

The healthcare professional should make a record that an assessment of suicide risk has been made and the person has no suicidal thoughts.

Suicidal ideation but no plan

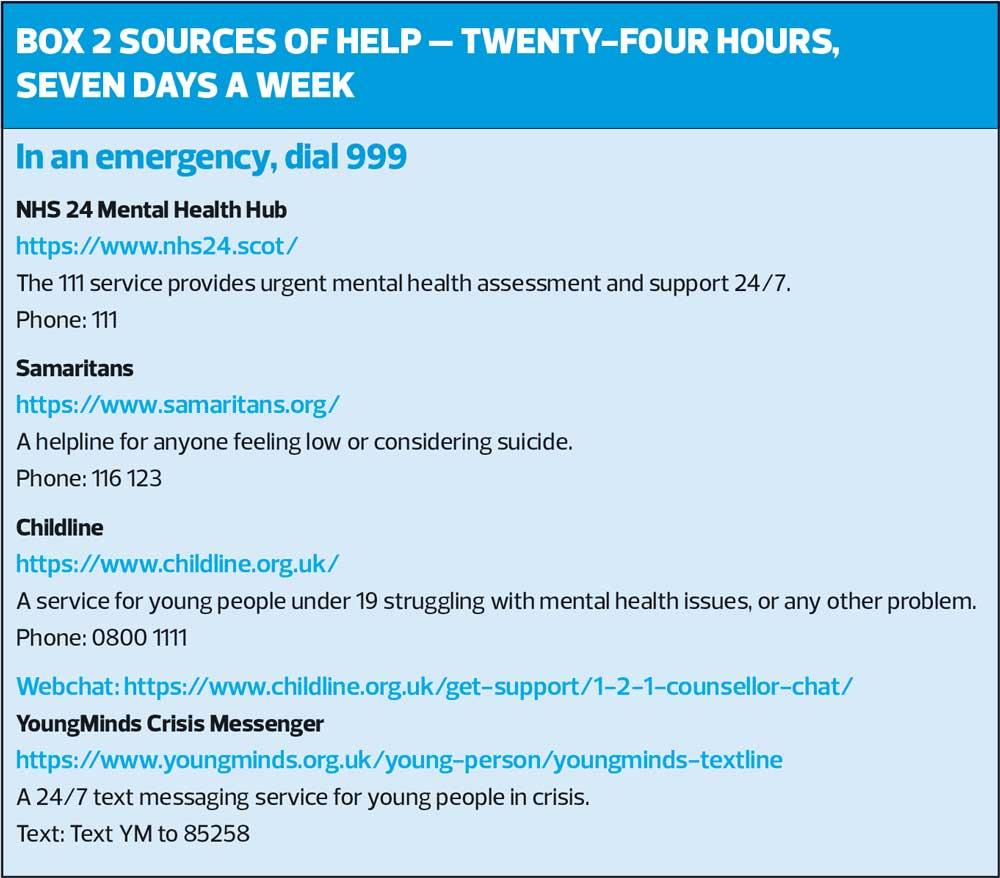

The healthcare professional should make a record that an assessment of suicide risk has been made and the person has suicidal thoughts but no current intent. Any advice and action should also be recorded. The person (and those involved in caring for them) should be advised:

- To immediately seek help (GP, Out of Hours service) if they start to think about making a plan, are concerned, or if their situation deteriorates

- Of sources of help available at all times (see Box 2)

- To be watchful for changes in mood, negativity and hopelessness, and suicidal intent, particularly during high-risk periods such as initiation of or changes to antidepressant medication or at times of increased stress.

Suicidal ideation with intent to carry out a plan

The healthcare professional needs to arrange immediate referral to mental health services following their local procedure.

Lifestyle advice

Poor lifestyle behaviours are considered prominent factors in the development of suicide risk.22 These include stress, substance and alcohol abuse, smoking, being sedentary, unhealthy diet and deficient sleep pattern. To be effective, information and advice about lifestyle behaviour should be personalised to each person by adapting it to their individual characteristics and interests.22

Online support

Practice nurses and primary healthcare professional should make themselves aware of national and local services for people who may be at risk of suicide and promote these to patients when appropriate. National online support includes:

- CALM: https://www.thecalmzone.net/

- National Self Harm Network: http://nshn.co.uk/

- Every Mind Matters: https://www.nhs.uk/oneyou/every-mind-matters/

- Switchboard LGBT+: https://switchboard.lgbt/

- Survivors of Bereavement by Suicide (SOBS) is a charity that supports people over 18 who have been bereaved by suicide, and also provides resources for professionals, at https://uksobs.org.

SUMMARY

Being aware of who may be at risk, how to screen for depression, and the interventions available will enable practice nurses and healthcare professionals in primary care to contribute to the prevention of suicide. Appropriate education and training are needed in order to achieve this, but using simple screening questions and ensuring that people are referred to receive help when it is needed can make a real difference.

REFERENCES

1. American Psychiatric Association. Suicide. 2021; https://www.apa.org/topics/suicide/

2. Oquendo M, Baca-Garcia E. Suicidal behavior disorder as a diagnostic entity in the DSM-5 classification system: advantages outweigh limitations. World Psychiatry 2014;13(2):128–130.

3. National Confidential Inquiry. National Confidential Inquiry into Suicide and Homicide by People with Mental Illness. Annual Report, England, Northern Ireland, Scotland and Wales. Manchester: University of Manchester, 2013.

4. National Confidential Inquiry. National Confidential Inquiry into suicide and homicide by people with mental illness: suicide in primary Care in England: 2002–2011. Manchester: University of Manchester, 2014.

5. World Health Organization. Suicide. 2021; https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/suicide

6. National Confidential Inquiry. Safer services: a toolkit for specialist mental health services and primary care, 2018. Available at: https://www.rcpsych.ac.uk/docs/default-source/improving-care/nccmh/suicide-prevention/safer-services_a-toolkit-for-specialist-mental-health-services_updated-nov-2018.pdf?sfvrsn=f6620787_2

7. Office for National Statistics. Suicide rates in the UK QMI. 2019. https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/birthsdeathsandmarriages/deaths/methodologies/suicideratesintheukqmi

8. Appleby L, Turnbull P, Kapur N, et al. New standard of proof for suicide at inquests in England and Wales. BMJ 2019; 366:l4745.

9. Office for National Statistics. Suicides in the UK: 2019 registrations. 2020; https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/birthsdeathsandmarriages/deaths/bulletins/suicidesintheunitedkingdom/2019registrations

10. Office for National Statistics. Suicides in the UK: 2017 registrations, 2018.

11. Department of Health. No Health Without Mental Health: A Cross-Government

Mental Health Outcomes Strategy for People of All Ages, 2011. London: Department of Health.

12. Department of Health. Preventing suicide in England: a cross-government outcomes

strategy to save lives, 2012. London: Department of Health.

13. Public Health England. Suicide Prevention Profile; 2019. https://fingertips.phe.org.uk/profile-group/mentalhealth/profile/suicide/data#page/0/gid/1938132828/pat/6/par/E12000004/ati/102/are/E06000015

14. Department of Health. Protect Life 2 - Suicide Prevention Strategy; 2019. https://www.health-ni.gov.uk/protectlife2

15. Leavey G, Mallon S, Rondon-Sulbaran J, et al. The failure of suicide prevention in primary care: family and GP perspectives – a qualitative study. BMC Psychiatry 2017;17(1):369. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-017-1508-7

16. Wylie C. Platt S, Brownlie J, et al. ‘Men, Suicide and Society.’ Samaritans Research Report, 2012. Ewell: Samaritans.

17. Webb R, Kontopantelis E, Doran T, et al. Suicide risk in primary care patients with major physical diseases: a case-control study. Arch Gen Psychiatry, 2012;69(3):256-64.

18. Morgan C, Webb R, Carr M, et al. Incidence, clinical management, and mortality risk following self-harm among children and adolescents: cohort study in primary care. BMJ 2017;359: j4351. Available at: www.bmj.com/content/359/bmj.j4351

19. Morgan C, Webb R, Carr M, et al. Self-harm in a primary care cohort of older people: incidence, clinical management and risk of suicide and other causes of death. Lancet Psychiatry, 2018;5(11):905-912.

20. Whooley M, Avins A, Miranda J, Browner W. Case-finding instruments for depression. Two questions are as good as many. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 1997;12(7):439-445.

21. NICE CG123. Common mental health disorders: identification and pathways to care; 2011. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg123

22. Berardelli I, Corigliano V, Hawkins M, et al. Lifestyle Interventions and Prevention of Suicide. Front Psychiatry. 2018;9:567.

23. Noordman J, Koopmans B, Korevaar J, et al. Exploring lifestyle counselling in routine primary care consultations: the professionals’ role. Family Practice, 2013;30(3):332–340.

Related articles

View all Articles