How to improve the physical health of people with severe mental illness

Dr Sheila Hardy

Dr Sheila Hardy

PhD, MSc, BSc (Hons), NISP, RMN, RGN

Mental health trainer, Practice Nurse Educator

Charlie Waller Trust

Practice Nurse 2021;51(3):9-12

The physical health of people with severe mental illness is worse than that of the general population and premature mortality is greater. But there are things that general practice nurses can do to encourage these patients to engage with primary care and improve their health

The primary care severe mental illness (SMI) register should include all patients with psychosis, schizophrenia, or bipolar disorder. In the UK, 6% of the population have experienced psychosis,1 1% have been diagnosed with schizophrenia and 2% with bipolar disorder.2

In this article we aim to help practice nurses to improve the physical health of the people with SMI in their care. By the end of the article, it is anticipated that you will:

- Understand how a person is affected by SMI

- Be aware of the physical health issues in SMI

- Consider how to make it easier for people with SMI to attend your practice

- Be motivated to look for ways to improve the physical health of the people with SMI registered with your practice

HOW A PERSON IS AFFECTED BY SMI

A person’s mental illness can have an effect on how they behave and communicate, their capacity to manage themselves and their understanding of any information and advice offered.

Psychosis is a symptom of mental illness, which makes it difficult for the person to differentiate between reality and their symptoms. They may perceive or read situations differently from everyone else. The two main types of psychosis are hallucinations and delusions.

- An hallucination involves seeing, hearing, smelling, tasting, or feeling something that does not exist. The most common kind are auditory where the person might hear someone speaking to them or telling them to do certain things. The voice they hear may be angry, neutral, or kind.

- A delusion is a belief held despite being contradicted by reality. There may be an aspect of paranoia where the person believes they are being spied on, or forced to do something against their will, or someone is planning to hurt them. Some people with psychosis think that they have some sort of power or authority.

They may be frightened or distressed if they are unaware that their hallucinations or delusions are not real.

A person with schizophrenia can experience positive, negative and cognitive symptoms.3

- The positive symptoms include hallucinations, delusions and thought disorder (thoughts and conversation appear illogical and lacking in sequence).

- The negative symptoms are an absence of behaviour that the person may have had previously. They may appear emotionally inexpressive and unresponsive, have poverty of speech, lack the desire for company, be unable to show or feel pleasure, and have a lack of will, spontaneity, and initiative.

- Cognitive symptoms include problems in concentration and task planning.

Someone with bipolar disorder will experience episodes of elated mood known as mania, and depression.3

- During a phase of mania, the person may feel euphoric and self-important, be full of energy and have new ideas, and plans. They often talk quickly, are easily distracted, irritated or agitated and do not sleep or eat. They may participate in pleasurable behaviour with upsetting consequences, such as spending large amounts of money or engaging in risky sexual encounters.

- During the depression phase the symptoms can include feeling sad and hopeless, empty or worthless, and guilty or despairing. The person may lack energy, have difficulty concentrating and remembering things, lose interest and enjoyment in everyday activities and experience self-doubt. Difficulties with sleeping and waking up early, and suicidal thoughts may also be present.

Symptoms of psychosis can be experienced during the mania or depression phase.

PHYSICAL HEALTH IN SMI

Studies show that there is a mortality gap between people with SMI and the general population of up to 25 years.4,5 The increased mortality is due to:

- Physical illnesses, with respiratory disease, diabetes and cardiovascular disease being the most common.6,7

- Economic disadvantage.8

- Unhelpful health behaviours (smoking, poor diet, lack of exercise, alcohol misuse).8

- Difficulties accessing and adhering to medical treatments.8

- The treatment given to this group: antipsychotic medication can contribute to the development of cardiovascular disease, diabetes and obesity.9,10

- Inadequate treatment for major medical conditions.11

- Neglecting self-care.12

People with SMI also have a high prevalence of other physical disorders such as sexually transmitted infections, erectile dysfunction, obstetric complications, osteoporosis, and dental problems.13 For those with cancer, they are more likely to have metastases at diagnosis and die prematurely than the general population and less likely to receive specialised interventions.14,15

MORTALITY IS NOT IMPROVING IN PEOPLE WITH SMI

The mortality of people with SMI has not improved despite more attention being given to this group.16 It can be argued that despite the fact that healthcare professionals in primary care offer an annual health check as required by the Quality and Outcome Framework (QoF), the needs of people with SMI are not always fully considered nor appropriate adjustments made. Additionally, the physical health check is often seen as a task to be carried out and completed annually rather than as an assessment to help both the healthcare professional and the person with SMI to work out what they should do next. It is also common for the symptoms of physical conditions to be viewed by healthcare professionals as part of the person’s mental illness.17

THE ROLE OF PRIMARY CARE

Healthcare professionals need to be mindful of the symptoms of people with SMI and consider why they might not respond to an invitation for a health check or engage in the treatment offered. Health services have a legal obligation to make reasonable adjustments to ensure that people with SMI are not disadvantaged compared with the general population in accessing healthcare.18

Making it easier of people with SMI to attend

People with SMI may be more likely to attend for an appointment and engage with the care offered if adjustments are made to make it easier for them. Due to the symptoms of their mental illness, people with SMI may not follow any instructions to attend or make an appointment, feel too anxious to attend, forget their appointment, or arrive late.19 If they have never been made aware of their risk of increased cardiovascular risk and other physical conditions, they may not see the benefit of attending.20

Inviting people with SMI for appointments

There are some simple ways of making the invitation for a health check more appealing.

- Letter: attendance can be increased by sending a letter with a predetermined date and time as it removes a complicated step in the process for the person with SMI.21 Including a straightforward description of the benefit of attending will increase their understanding.20 A short prompt letter offering gentle encouragement and explanation sent a few days before the appointment can also help.22

- Telephone: attendance may be improved by inviting people to attend by telephone23 or endorsed text message reminder.24

- Prompting from a third party such as the community mental health team (CMHT) may encourage the person to come.25

Appointment arrangements

There are some practical considerations which may make it easier for the person with SMI to attend.

- Time of appointment: some people with SMI find it difficult to get up due to their symptoms and medication side effects, so appointments later in the day may be more convenient.

- Duration of appointment: a prolonged appointment which offers a lot of information may be overwhelming, although there is a risk of them not returning if all measures are not completed. Providing the information in a concise manner, explaining the advantages of coming back, and booking any further appointments while they are with you can help.

- Quiet waiting area: anxiety can be caused by a waiting room that is noisy and full of people and waiting for a long period of time may make a person with SMI feel agitated. Providing a separate quiet waiting area, or organising appointments at a time of day which is not busy can help to avoid this.

THE PHYSICAL HEALTH CHECK

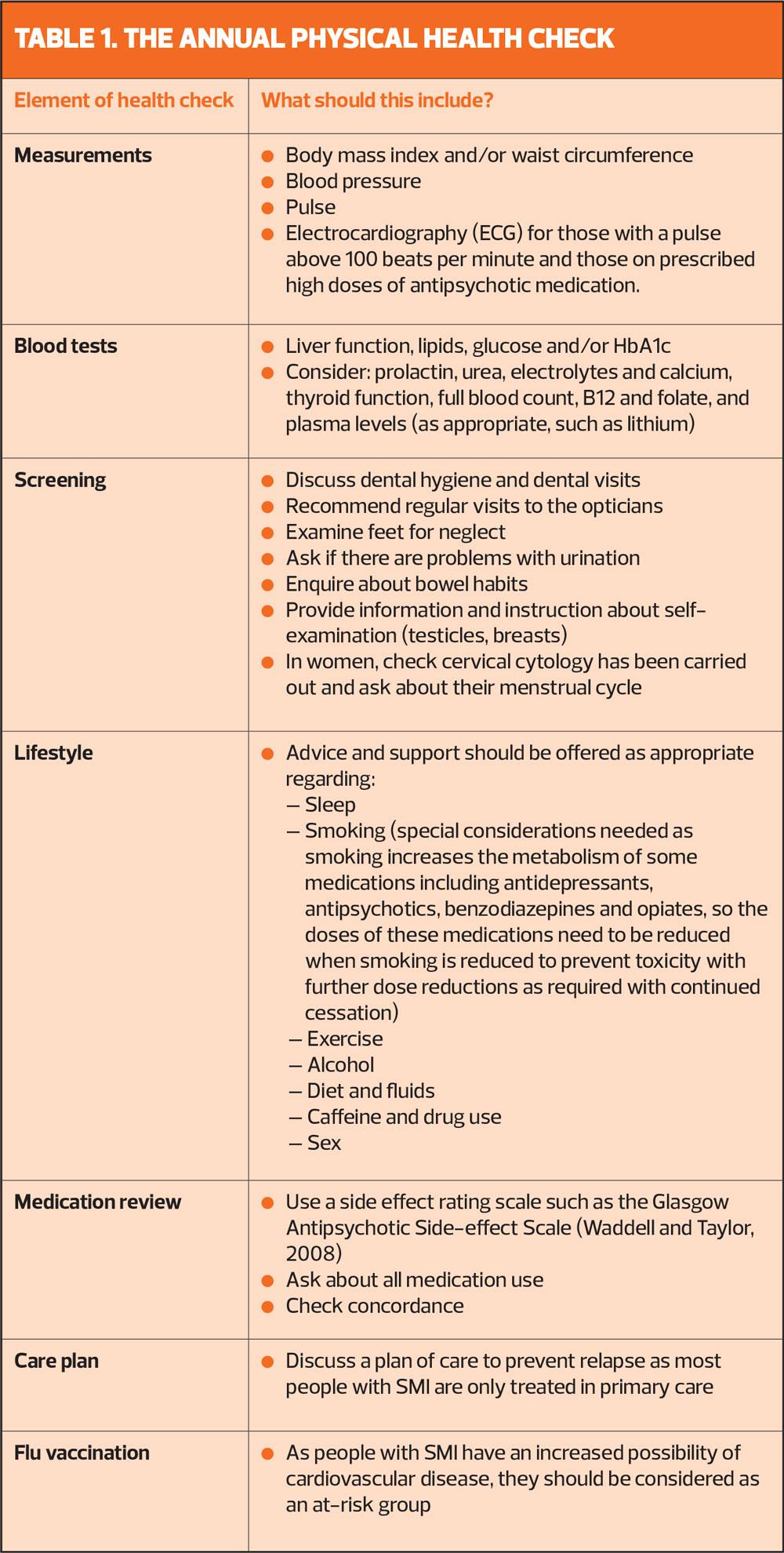

A person with SMI should be offered a physical health check annually when responsibility for monitoring is transferred from secondary care.25 Most of the recommended elements of this check are comparable to those advised for other long-term conditions, so healthcare professionals in primary care will already be familiar with them. We recommend that a health check in primary care should consist of measurements, blood tests, screening, lifestyle, medication review and a care plan19 – see Table 1. A manual which describes each element in detail is available from our website http://physicalsmi.webeden.co.uk/

AFTER THE HEALTH CHECK

If the person with SMI is not offered any further help and support following their physical health check, their health and mortality is very unlikely to improve.26 For morbidity and mortality to be reduced, any identified unhealthy behaviour needs to be modified. This group is able to work with healthcare professionals to learn how to make lifestyle adjustments.27 Research looking at primary care nurses and healthcare assistants supporting people with SMI to change their behaviour, found appointments were well attended.28 If a person with SMI is referred to a structured group education such as weight management the health care professional should continue to see them to ensure attendance and engagement.29

SUMMARY

It is the responsibility of healthcare professionals working in primary care to provide physical health checks for people with SMI. To ensure engagement of this group, some practical modifications may need to be put in place when arranging appointments. The healthcare professionals should support the person with SMI with any lifestyle changes they wish to make following their health check.

REFERENCES

1. McManus S, Bebbington P, Jenkins R, et al. Mental health and wellbeing in England: Adult Psychiatric Morbidity Survey 2014. 2016 content.digital.nhs.uk

2. MHFA England. Mental Health Statistics. 2019 https://mhfaengland.org/mhfa-centre/research-and-evaluation/mental-health-statistics/#psychosis-and-schizophrenia

3. American Psychiatric Association (APA). The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th edition. Arlington (VA): APA. 2013.

4. Firth J, Siddiqi N, Koyanagi A, et al. The Lancet Psychiatry Commission: a blueprint for protecting physical health in people with mental illness. The Lancet Psychiatry 2019;6(8):675-712.

5. Hayes J, Marston L, Walters K, et al. Mortality gap for people with bipolar disorder and schizophrenia: UK-based cohort study 2000–2014. The British Journal of Psychiatry 2017;211(3):175-181.

6. Barber S and Thornicroft G. Reducing the mortality gap in people with severe mental disorders: the role of lifestyle psychosocial interventions. Frontiers in Psychiatry 2018;9:463. doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2018.00463

7. Liu N, Daumit G, Dua T, et al. Excess mortality in persons with severe mental disorders: a multilevel intervention framework and priorities for clinical practice, policy and research agendas. World Psychiatry 2017;16(1):30-40.

8. Olfson M, Gerhard T, Huang C, et al. Premature mortality among adults with schizophrenia in the United States. JAMA Psychiatry 2015;72:1172–81.

9. Torniainen M, Mittendorfer-Rutz E, Tanskanen A, et al. Antipsychotic treatment and mortality in schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin 2015;41:656–63.

10. Mitchell A, Vancampfort D, Sweers K, et al. Prevalence of metabolic syndrome and metabolic abnormalities in schizophrenia and related disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Schizophrenia Bulletin 2013;39:306–18.

11. Woodhead C, Ashworth M, Broadbent M, et al. Cardiovascular disease treatment among patients with severe mental illness: a data linkage study between primary and secondary care. British Journal of General Practice 2016;66:e374–81.

12. Wu C, Chang C, Hayes R, et al. Clinical risk assessment rating and all-cause mortality in secondary mental healthcare: the South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust Biomedical Research Centre (SLAM BRC) Case Register. Psychological Medicine 2012;42: 1581–1590.

13. De Hert M, Correll C, Bobes J, et al. Physical illness in patients with severe mental disorders. I. Prevalence, impact of medications and disparities in health care. World Psychiatry 2011;10:52–77.

14. Bushe C, Taylor M, Haukka J. Mortality in schizophrenia: a measurable clinical endpoint. J Psychopharmacol 2010;24(4_supplement):17–25.

15. Kisely S, Crowe E, Lawrence D. Cancer-Related Mortality in People With Mental Illness. JAMA Psychiatry 2013;70(2):209-217.

16. Mitchell A, Hardy S, Shiers D. Parity of Esteem: addressing the inequalities in mental health care as compared with physical health care. B J Psych Advances 2017;23(3):196-205.

17. Nash M. Diagnostic overshadowing: a potential barrier to physical health care for mental health service users. Journal of Mental Health Nursing 2013;17(4):22-26.

18. Equality Act. When a mental health condition becomes a disability. 2010 https://www.gov.uk/when-mental-health-condition-becomes-disability

19. Hardy S. Improving physical health in people with severe mental illness. Practice Nursing 2020;31(11):456 – 460.

20. Hardy S. Physical health checks for people with severe mental illness. Primary Healthcare 2013;23(10):24-26.

21. Hardy S, Gray R. Is the use of an invitation letter effective in prompting patients with severe mental illness to attend a primary care physical health check? Primary Health Care Research & Development 2012;13(4):347-352.

22. Perron N, Dao M, Kossovsky M, et al. Reduction of missed appointments at an urban primary care clinic: a randomised controlled study. BMC Fam Pract 2010;11:79.

23. Gidlow C, Ellis N, Riley V, et al. Randomised controlled trial comparing uptake of NHS Health Check in response to standard letters, risk-personalised letters and telephone invitations. BMC Public Health 2019;19:(224). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-019-6540-8

24. Sallis A, Sherlock J, Bonus A, et al. Pre-notification and reminder SMS text messages with behaviourally informed invitation letters to improve uptake of NHS Health Checks: a factorial randomised controlled trial. BMC Public Health 2019;19:1162. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-019-7476-8

25. NICE CG178. Psychosis and schizophrenia in adults: treatment and management. 2014 http://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg178/resources/guidance-psychosis-and-schizophrenia-in-adults-treatment-and-management-pdf

26. Chew Graham C, Chitnis A, Turner P, et al. Why all GPs should be bothered about Billy. B J Gen Pract 2014;64(618):15.

27. Alvarez-Jimenez M, Hetrick S, González-Blanch C, et al. Non-pharmacological management of antipsychotic-induced weight gain: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. B J Psychiat 2008;193:101–107.

28. Osborn D, Burton A, Walters K, et al. Primary care management of cardiovascular risk for people with severe mental illnesses: the Primrose research programme including cluster RCT. Programme Grants Appl Res 2019;7(2).

29. Holt R, Gossage-Worrall R, Hind D. et al. Structured lifestyle education for people with schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder and first-episode psychosis (STEPWISE): randomised controlled trial. The British Journal of Psychiatry 2018 doi: 10.1192/bjp.2018.167.

Related articles

View all Articles