Testosterone deficiency and the practice nurse

Jane Thomas

Jane Thomas

RGN

Porthcawl Medical Centre, Porthcawl, Bridgend

Practice Nurse 2020;50(9):16-19

Low testosterone levels are more common than you may think but men’s reluctance to engage with health services – and embarrassment about symptoms as personal as erectile dysfunction – mean that deficiency often remains undiagnosed. GPNs can play a pivotal role in its detection

Testosterone deficiency is becoming increasingly common in men in the UK yet is frequently underdiagnosed and undertreated.1 Low testosterone levels occur in over 40% of men with type 2 diabetes and are associated with an increased risk of erectile dysfunction (ED), more severe ED, increased adiposity, insulin resistance, poor glycaemic control, dyslipidaemia and increased mortality.2-4

Being a man has significant health risks, which are often ignored particularly as men don’t tend to engage with the healthcare system as women do. One of the possible reasons for this is that there is routine screening available for women such as cervical screening and the mammogram screening programme. No such regular routine screening is available to men.In addition to the more obvious effect, ED, testosterone deficiency is associated with various cardiovascular risk factors, increased mortality and decreased quality of life.5-9 It also associated with obesity and a number of comorbidities, the most common of which are diabetes, hypertension, hyperlipidaemia, osteoporosis and asthma or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.7

The prevalence of type 2 diabetes is increasing rapidly worldwide.10 ED is one of the most common symptoms of testosterone deficiency and may be a predictor of type 2 diabetes and conversely, this condition is one of the most frequent organic causes of ED.11 NICE guidelines recommend that men with type 2 diabetes should be offered the opportunity to discuss ED as part of their annual review,12 but although it is one of the most frequent chronic health problems in men it is often missed either through a lack of awareness or through embarrassment on the part of either the patient or the healthcare professional and reluctance to discuss or raise the topic.13 The percentage of men with type 2 diabetes who are identified has having ED has reduced considerably as questioning is no longer part of the Quality and Outcomes Framework (QOF).

SCREENING

British Society for Sexual Medicine (2017) guidelines recommend that all men with ED are screened for low testosterone.14 However, a recent audit showed that two thirds of men with type 2 diabetes had neither been asked about ED nor had a testosterone test in the last 24 months, and a substantial proportion of men with type 2 diabetes, low testosterone and ED were not receiving treatment in line with evidence-based guidelines.15

Men are more likely than women to die of cardiovascular disease (CVD) between the ages of 45 and 80 years.16 Epidemiological studies have shown that low testosterone is an independent risk factor for both CVD and all-cause mortality.17 ED is an indicator of heart disease in the QRISK and Joint British Societies (JBS) CVD risk calculators (https://qrisk.org/three/ and http://www.jbs3risk.com/)

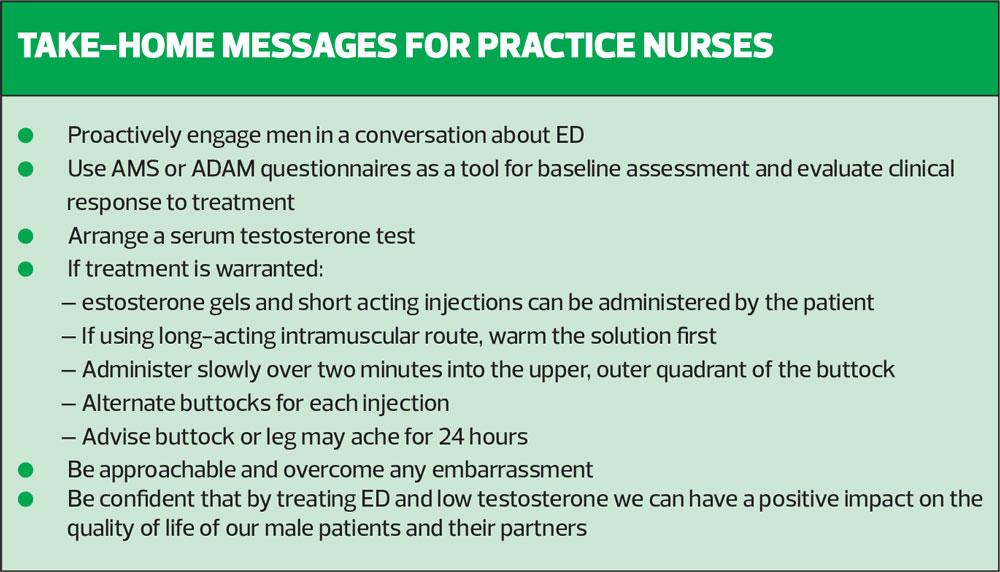

Practice nurses can play a pivotal role in detecting low testosterone particularly men at high risk by identifying and addressing their concerns during routine appointments or in chronic disease management clinics.

Who should be screened for testosterone deficiency?

- Adult men with consistent and multiple signs of ED

- All men presenting with ED, loss of spontaneous erections or low sexual desire

- All men with Type 2 diabetes mellitus, BMI>30kg/m? or waist circumference >102cm (40.2 inches)

- All men on long-term opiate, antipsychotic or anticonvulsant medication14

Practice nurse should consider screening baseline testosterone levels for men who are symptomatic or have clinical conditions associated with low testosterone levels before referring to the patient’s GP to confirm the diagnosis.

Screening

1. Measure: height, weight, BMI and waist circumference

2. Enquire about previous and current prescription and non-prescription drug use, as many drugs, such as opioids, glucocorticoids, anti-convulsants and anti-psychotics can cause testosterone deficiency due to their impact on the hypothalamic-pituitary-testicular (HPT) axis

3. Consider: the use of validated questionnaires such as the Androgen Deficiency in the Ageing Male (ADAM) (see appendix 1) available at: http://sexualadviceassociation.co.uk, or the Ageing Males’ Symptoms (AMS) Scale (See Appendix 2), available at: http://www.issam.ch/AMS_English.pdf

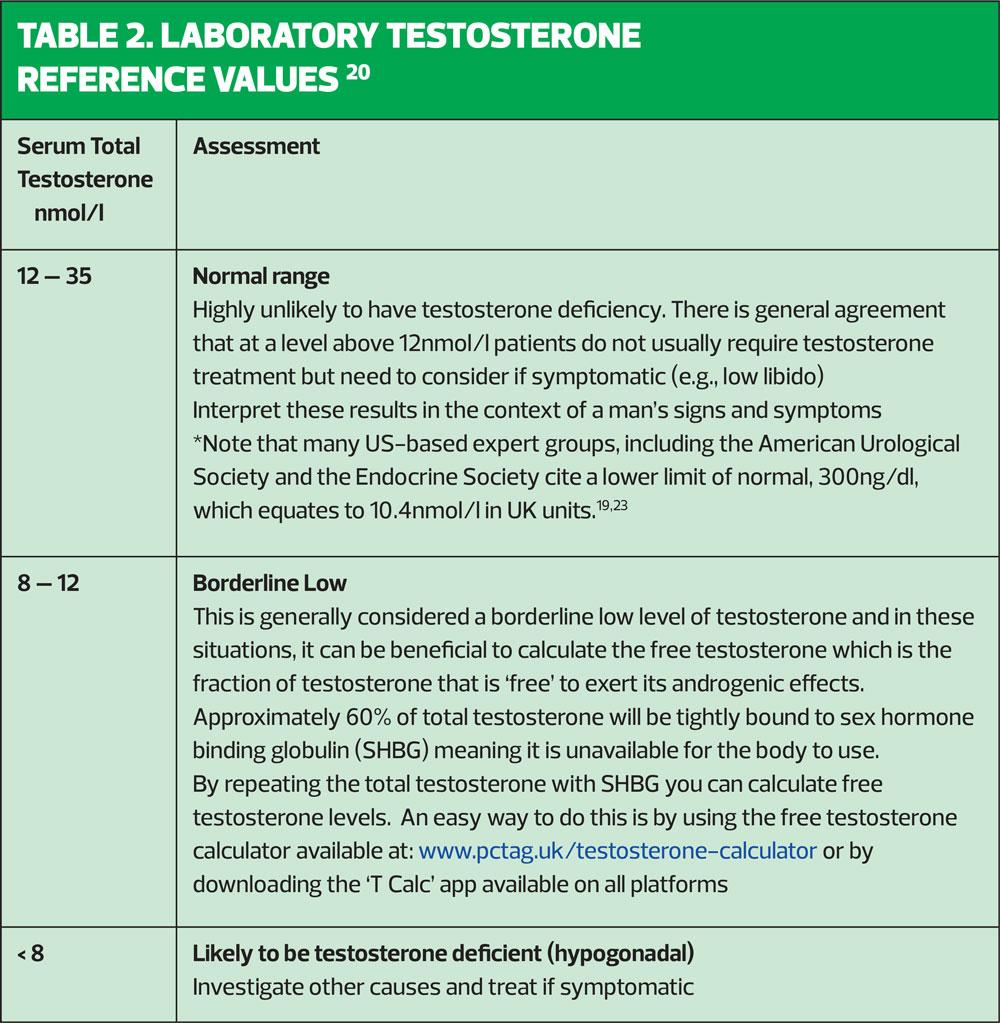

4. Serum testosterone levels should be measured between 7-11am, preferably 4 weeks apart. Fasting levels of testosterone have been shown to be up to 30% higher than non-fasting levels in volunteer and normal population studies involving a 75-g glucose load. Therefore, fasting levels should be obtained where possible, as recommended by the European Association of Urology.

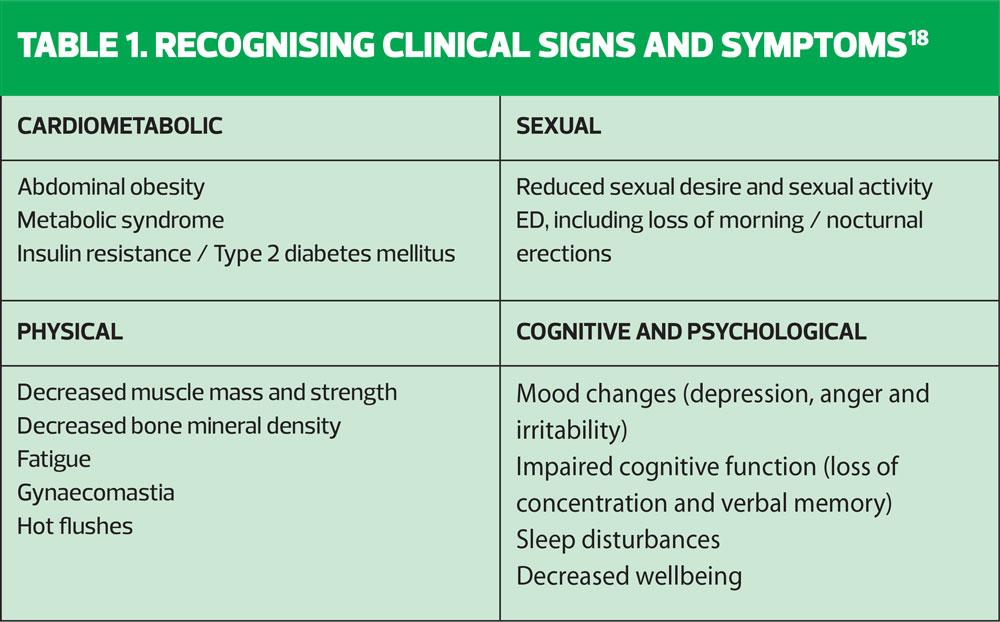

Clinical signs and symptoms are shown in Table 1. These symptoms need not all be present to identify the condition; a diagnosis of testosterone deficiency is based on characteristic signs and symptoms and low serum testosterone concentrations measured on at least two separate occasions.19

MANAGEMENT OF TESTOSTERONE DEFICIENCY

The goal of testosterone deficiency treatment is to improve signs and symptoms and the man’s overall quality of life, by restoring testosterone levels to the normal physiological range. This involves a number of strategies including exercise and diet modification to reduce weight, improve muscle strength, enhance emotional well-being, improve metabolic parameters (HbA1c, lipids, waist circumference and blood pressure), as well as prescribing testosterone replacement therapy where appropriate.

A holistic approach to treatment is needed that considers the patient’s symptoms as well as his laboratory results and includes the patient in decision making.

Pharmacological treatments

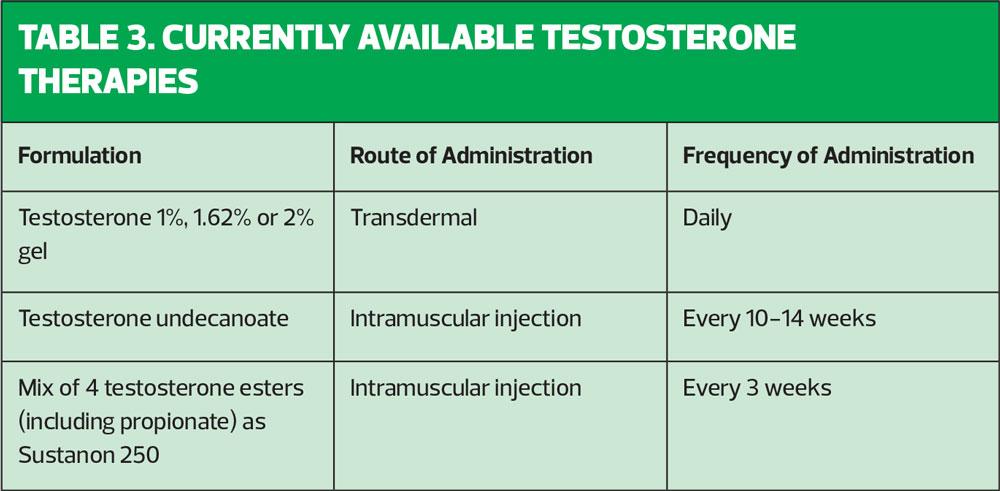

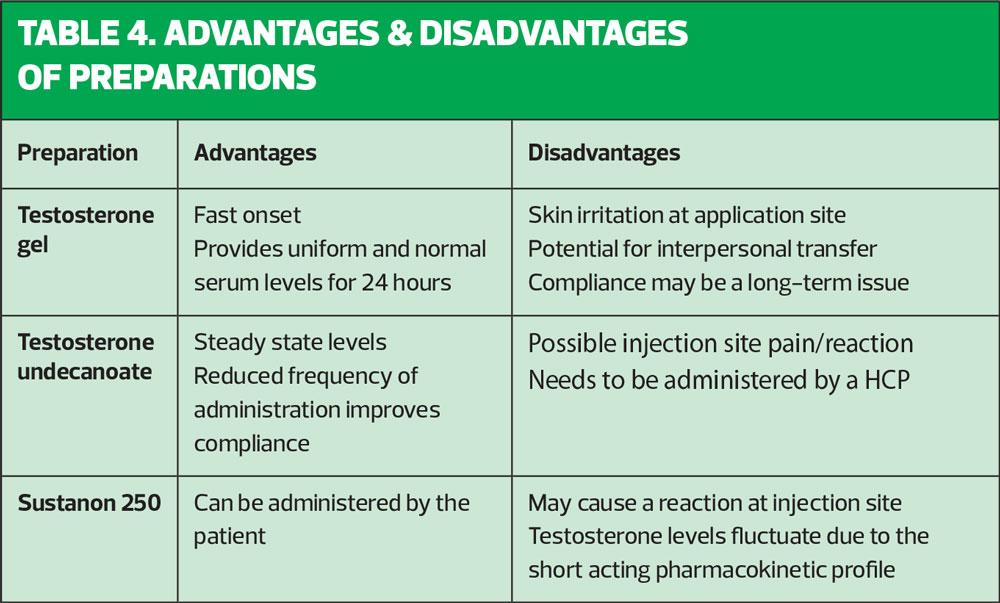

There are several testosterone preparations available that differ in their route of administration. The patient should be fully informed about the expected benefits and side effects of each in order that he can make an educated decision on choice of treatment (Tables 3,4).

Contraindications to testosterone therapy

Prior to initiating testosterone therapy there are certain criteria that need to be ruled out. The BSSM guidelines list the following contraindications to testosterone therapy:

- Known or suspected prostate cancer

- Male breast cancer

- An active desire to have children (testosterone therapy can reduce fertility by suppressing FSH production)

- Haematocrit higher than 54%

- Severe chronic heart failure (New York Heart Association class IV)

Timeline of symptom improvement 21

If symptomatic improvement is not initially seen, prior to abandoning therapy, testosterone levels need to be checked.

AT 3 MONTHS

- Increased energy

- Improved emotional well-being

- Enhanced libido

- Reduced ED

AT 6 MONTHS

- Increased strength

- Improvement in some components of metabolic syndrome

- Improved cognition

- Enhanced cardiovascular health

- Decreased body fat

12 MONTHS ONWARDS

- Enhanced bone mineral density (BMD)

FOLLOW UP AND MONITORING22

After initiation of testosterone therapy, it is recommended that patients are evaluated at 3, 6 and 12 months and every 12 months thereafter to assess serum testosterone levels, confirm symptomatic improvement and check for any treatment emergent adverse events.

At these review appointments it is also essential to measure the PSA and haematocrit level and perform a digital rectal exam (DRE) to check for changes to the prostate as testosterone replacement therapy is contra-indicated in active prostate cancer.

Testosterone is known to stimulate erythropoiesis although the exact mechanism for this is poorly understood. An increased haematocrit level above 54% would warrant action to reduce it. This can either be done by stopping testosterone treatment (easier with gels that are applied daily) or by venesection. Once the haematocrit is normalised, the testosterone therapy can be reintroduced, often at a reduced dose.

Failure to benefit from treatment within a reasonable time frame (defined as 6 months for libido, sexual function, muscle function and improved body fat) should prompt discontinuation and investigation for other causes of symptoms.

In our practice, we added a serum testosterone level check to the annual diabetic blood checks. When patients attended for their follow up check in diabetic clinic, I asked if they would mind completing one of the aforementioned questionnaires ADAM or AMS. I consequently found this seemed to encourage them to start talking about their concerns and was able to have a frank discussion with them particularly about ED. If their testosterone was shown to be low, I would then explain that this could be a cause and offer them an appointment with their GP to discuss it, which the majority of them were willing to do. Since starting the screening we have gone from having 0 patients being treated with testosterone to more than 100, out of a practice population of 15,500.

In order to evaluate whether treatment was effective I would ask them to complete a further questionnaire 6 to 12 months after initiation. The majority of patients have reported significant improvement in their general wellbeing.

CASE STUDIES

Case Study 1

Simon, a 58-year-old building site manager with type 2 diabetes, attended diabetic clinic and complained of extreme tiredness, mood swings, felt that he got angry at ‘any little thing’ and had a lack of concentration. On further questioning he felt that his marriage was suffering due to his ‘inability to perform sexually’. On checking his testosterone result that had been taken with his routine annual diabetic bloods, I noted that it was 5.8 nmol/l which is profoundly low. He completed the AMS questionnaire and his score was 45, indicating moderate symptoms. I explained the significance of these findings and offered him an appointment with the GP to discuss further. Following this appointment Simon had a repeat testosterone level, which was also found to be low, so he was started on testosterone gel. Two years later at his annual review he had a testosterone level of 16.1nmol/l, his AMS score had reduced to 33, HbA1c had reduced from 58 mmol/mol to 50 mmol/mol and waist circumference from 48 inches to 44 inches. Simon reported that his life had improved dramatically, along with his marriage.

Case Study 2

Robert, 60 years, had initially presented to the GP with ED. He was overweight with a BMI of 34 kg/m2 and complained of lethargy and nocturnal dysuria. Following further investigations he was diagnosed with type 2 diabetes, with a HbA1c of 60 mmol/mol, and found to have very low testosterone (4.2nmol/l). His AMS score was 48, and waist circumference 46 inches. Robert was referred to me as he had decided opted to have his testosterone replacement therapy by intramuscular injection: because he worked away from home during the week he feared he would not be compliant with the daily application of gel. He also attributed his weight issues to his work lifestyle, as he often ate convenience or fast food while away and was generally unable to maintain a healthy diet.

Robert had his first injection followed by a second ‘loading dose’ at six weeks, and a third injection at 12 weeks after the second. Trough level bloods (testosterone, FBC and PSA) were taken 10 weeks after the third injection to determine the interval of his subsequent injections.

Two years on he said he felt like ‘a new man’. His testosterone level had increased to 15.9nmol/l, HbA1c reduced to 39mmol/mol and he had lost an incredible 4 stone in weight bringing his weight circumference down to 34 inches. His AMS score was 29 and libido much improved. Robert felt that his diagnosis had made him re-evaluate his health and wellbeing, he has semi -retired and now walks five to seven miles a day. Independently, when attending a well woman clinic, his wife volunteered that ‘it has totally rekindled our marriage’ – which shows that improving men’s health and well-being can also improve quality of life for their partner.

Case Study 3

Richard, 48-year-old sales representative, attended for an ECG as he had been experiencing some chest discomfort and was concerned as his father had died after a myocardial infarction at the age of 52. I asked him about his overall general health, he stated that he had not been feeling ‘brilliant’ lately, was tired all the time and had lost all interest in life in general. I proceeded to ask him about his sexual function and he admitted it wasn’t great but had put all his symptoms down to his busy lifestyle and job. I added a serum testosterone level to the bloods that had been requested to assess his cardiovascular risk and asked him if he wouldn’t mind completing a questionnaire. He was ultimately found to have a low testosterone and was treated. This case study shows that with a greater awareness, GPNs can detect these patients during routine appointments.

CONCLUSION

The GPN is more likely to see men routinely than GPs as they manage the chronic disease clinics. It is often difficult to bring up the subject of ED due to embarrassment on both the sides, but as seen in the case studies we can play an important role in improving men’s health and sense of wellbeing by overcoming this embarrassment. In my case I find the use of the questionnaires a valuable tool, as it opens up the conversation. I now give every man a questionnaire and even if they don’t want a discussion there and then they often return having read it.

Despite the well documented relationship between type 2 diabetes, ED and low testosterone, many men are not assessed for either condition, and this can lead to a valuable opportunity being missed to diagnose and record these conditions which could subsequently improve the overall health outcomes for this group.

REFERENCES

1. Edwards D, David J, Olding L. Lack of awareness contributes to delayed diagnosis and inappropriate management in men with low testosterone: findings from a UK survey of men diagnosed with hypogonadism. /Sex Med 2016;13:S77-8

2. Cheung KK, Luk, So WY et al (2015) Testosterone level in men with type 2 diabetes mellitus and related metabolic effects: A review of current evidence. / Diabetes Investig 6: 112-23

3. Chiles KA (2016) Hypogonadism and erectile dysfunction as harbingers of systemic disease. Transl Androl Urol 5: 195-200

4. Hackett G, Heald AH, Sinclair A et al (2016a) Serum testosterone, testosterone replacement therapy and all cause mortality in men with type 2 diabetes: retrospective consideration of the impact of PDE5 inhibitors and statins. Int J Clin Pract 70: 244-53

5. Antonio L, Wu FC, O’Neill TW, Pye SR, Carter EL, Finn JD, et al. Associations between sex steroids and the development of metabolic syndrome: a longitudinal study in European men. J Clin Endocrinal Metab 2015; 100:1396-404

6. Kelly DM, Jones TH, Testosterone and cardiovascular risk in men: Front Horm Res 2014; 43:1-20

7. Mulligan T, Frick MF, Zuraw QC, Stemhagen A, McWhirter C. Prevalence of hypogonadism in males aged at least 45 years: The HIM study. Int J Clin Pract 2006: 762-9

8. Nigro N, Christ-Crain M. Testosterone treatment in the ageing male: myth or reality? Swiss Med Wkly 2012;142:w13539

9. Wang C, Jackson G, Jones TH, Matsumoto AM, Nehra A, Perelman MA, et al. Low testosterone associated with obesity and the metabolic syndrome contributes to sexual dysfunction and cardiovascular risk in men with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care 2011;34:1669-75

10. World Health Organization (2016) WHO global report on diabetes. WHO, Geneva, Switzerland. Available at: http://www.who.int/diabetes/global-report/en

11. Mazzilli RJ, Elia M, Delfino F, et al (2015) Prevalence of Diabetes Mellitus (DM) in a population of men affected by Erectile Dysfunction (ED). Clinical Ther 166: e317-20.

12. NICE (2015) Type 2 diabetes in adults: management (NG28). NICE, London Available at: http://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng28

13. Grant P, Jackson G, Baig I, Quin J (2013) Erectile Dysfunction in General Medicine. Clin Med (Lond) 13: 136-40

14. British Society for Sexual Medicine (2017) Guidelines on the Management of erectile dysfunction, BSSM London

15. David J, Edwards D, Wright P. REVITALISE audit: erectile dysfunction and testosterone review in primary care. Diabetes Prim Care 2017: 19: 67-72

16. Leening MJG et al: Sex differences in lifetime risk and first manifestation of cardiovascular disease: prospective population based cohort study. BMJ 2014;349:g5992

17. Maggio M, Basaria S. Welcoming low testosterone as a cardiovascular risk factor. Int j Import Res 2009;21:261-4

18. British Society for Sexual Medicine. A Practical guide on the assessment and management on testosterone deficiency in adult men 2018 (April 2018). http://www.bssm.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/BSSM-Practical-Guide-High-Res-single-pp-view-final.pdf

19. Bhasin S, Cunningham GR, Hayes FJ, Matsumoto AM, Snyder PJ, Swerdloff RS, et al. Testosterone therapy in men with androgen deficiency syndromes: an Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2010;95:2536-59.

20. Men’s Health Review Panel. Men’s Health Handbook for General Practice. Toronto: MUMS Guidelines Clearinghouse; 2019

21. Morales a et al Can Urol Assoc J 2010;4(4):269-75 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2910774/pdf/cuaj-4-269.pdf

22. British Society for Sexual Medicine Guidelines on Adult Testosterone Deficiency, with Statements for UK Practice: available at: http://www.bssm.org.uk/wp-content/uploads2017/12/guidlines-on-adult-testosterone-deficiency-with-statements-for-uk-practice.pdf

23. Mulhall, JP et al. Evaluation and management of testosterone deficiency: AUA Guideline J Urol. 2018 Aug;200(2):423-432

Related articles

View all Articles